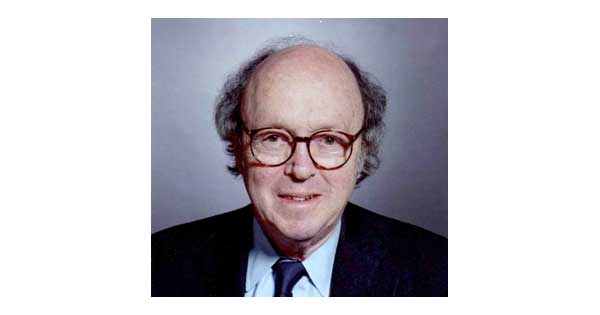

Anthony Lewis and the March to Equality

In his writing, he explained an activist Supreme Court to the nation

“The Constitution remains our fundamental law,” Anthony Lewis wrote, “because great judges have read it in that spirit.” Covering the Supreme Court for The New York Times in the 1960s, he was on hand when justices on the Warren Court did just that. Simply and eloquently, he explained how they made the court a central arbiter in American life and shaped the country’s march toward equality.

Lewis, who died March 25 at 85, played an extraordinary role in that shaping. The court’s landmark decisions about racial justice, one person-one vote, and other deeply destabilizing social issues took hold because of the trust of the American people. Lewis helped foster that trust, through the authority and humane intelligence of his reporting and writing.

He was a liberal, in the tradition of justices Louis Brandeis at the beginning of the 20th century and William Brennan Jr. at the end, and was a brilliant scold when the government infringed on civil liberties.

He won his first Pulitzer Prize in 1955 at the age of 28 for clearing the name of an employee of the U.S. Department of the Navy, which restored the man to duty and acknowledged it had committed a grave injustice in dismissing him as a security risk.

His second Pulitzer came in 1963 when he was 36 for his coverage of reapportionment of state legislatures and the Supreme Court’s mandate for equal representation in voting districts. He became a Times columnist and, for 32 years, commented influentially about foreign and domestic affairs, but he continued to shine as the law’s premier explainer.

“Change does not just begin at a point in time,” Lewis wrote; “it builds on history.” In his two classic books of nonfiction, he demonstrated the truth in that remark.

Gideon’s Trumpet is a bestselling introduction to the Supreme Court and its capacity to raise the standards of American justice. Published in 1964, it focuses on the 1963 case of Gideon v. Wainwright, in which a poor prison inmate in Florida named Clarence Gideon persuaded the court to overturn a major precedent and find that the Constitution guarantees every criminal defendant the right to effective counsel.

Lewis’s Make No Law is among the best books ever written about the American legal system. Published in 1991, it describes the 1964 case New York Times v. Sullivan, one of the court’s most vital rulings on the First Amendment. The book tells the story of a libel case brought by a city commissioner in Montgomery, Alabama, and how the state’s libel law, unforgiving about even minor factual errors by news outlets, threatened to keep the Times from reporting about the furor over desegregation in the South.

Lewis recounted how the justices unanimously stood up for a free press. They ensured robust reporting on public affairs by using the First Amendment to make it more difficult for officials and other public figures to bring and win libel suits throughout the country.

The story he told about the transcendence of the Supreme Court in that era captured the institution as a pillar of national progress. His uncommon writing about the majesty of government when the courts hold it accountable to law instructed how the United States can achieve that kind of progress. In the spirit of that quest, he wrote important journalism and lasting history.

Lewis was an avid teacher and mentor, to Linda Greenhouse who covered the Supreme Court superbly for the Times for a generation and to other accomplished journalists. Although he taught me at Harvard Law School and generously blurbed a book I wrote, he was not a mentor for me. Instead, he was an inspiration.

He possessed a vivid, passionate intellect, and had the moral focus of a rabbi. He worked intensely in the texts, the talk, and the traditions of the Court, but that effort appeared to be an immersion more than work. The lesson I drew from his model was that, even for someone as gifted as he, hard work was essential to giving the Court its due—especially so for those of us following the Court who don’t have the exceptional gifts he had.

Because he had extraordinary access to justices and his writing helped elevate the stature of the Supreme Court, he was sometimes criticized as an insider and, in some sense, a captive of the institution. But when it let him down, as it did dramatically in Bush v. Gore, making a political ruling to throw the 2000 election to George W. Bush, he reminded readers of his uncompromising independence.

He loved the Supreme Court as an American institution, but loved the Constitution more. Another lesson I drew from his model was that, while the Court always deserves the respect of anyone covering it, that respect sometimes requires saying sharply why you think a ruling it makes is wrong.

And why you think a ruling is worth celebrating. The title Gideon’s Trumpet is from the Bible, from the Book of Judges in the Old Testament: “But the Spirit of the Lord came upon Gideon, and he blew a trumpet.”

Anthony Lewis’s voice was from the Old Testament as well—awe-inspiring, judgmental, and righteous.