Worm: The First Digital World War, By Mark Bowden, Atlantic Monthly Press, 245 pp., $25

You know not to respond to online pitches from Nigeria for money. You are wary of email requests for your credit card number. You don’t open attachments from people you don’t know. Your passwords include the requisite amount of numbers and capital letters, and you update your antivirus software often. If this describes you, pat yourself on the back because your computer—your virtual archive, your locked safe, the sum of your modern life—is impregnable. Hackers, identity thieves, and other virtual bad guys can’t get you, right?

Of course they can. They can get anybody, slipping into the most well-defended networks with a mere tweak of code. On some level, all computer users and Internet surfers, as technologically ignorant as we mostly are, know the system is vulnerable. We just don’t want to think about it. As Internet pioneer Paul Vixie puts it in Mark Bowden’s Worm, “These problems [with Internet security] have been here so long that the only way I’ve been able to function at all is by learning to ignore them. Else I would be in a constant state of panic.”

Bowden wants you to panic. Perhaps that’s too strong. He wants you to understand that we are threatened with “a virtual apocalypse, a meltdown out there in the parallel universe of incomprehensible computer systems.” Worm, the latest book from the author of Black Hawk Down, recounts how an ad hoc team of cybersecurity experts called the Cabal prevented a worm dubbed Conficker from taking down the Internet, at least for now.

The first sign of danger appeared on Phil Porras’s computer screen in the Menlo Park, California, offices of SRI International on November 20, 2008. Porras, an Internet security expert, tracks malware, the nasty viruses and worms that infect computers (a virus requires human action to spread; a worm is a program that can propagate on its own). That evening, he noticed a worm more contagious than any he had ever seen.

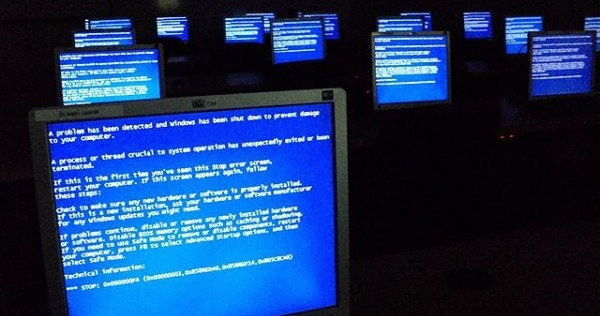

“The worm,” writes Bowden, “was targeting … Port 445 of the Windows Operating System, the most commonly used operating software in the world, causing a buffer at that port to overflow, then corrupting its execution in order to burrow into the host computer’s memory.” Conficker didn’t appear to slow the operation of the host computer, but whoever had designed the worm seemed to be using it to build a “botnet,” a network of enslaved computers awaiting the malware programmer’s commands. Once the worm had infected a machine, it would contact the computer’s Internet service provider to send itself to all the other vulnerable computers on that network. Then, on a date set by the botmaster (November 26, 2008, for the worm’s first iteration), the worm would begin to contact a list of 250 domain names. The botmaster would be waiting at one of those addresses to issue his orders. The combined computing power of a large bot- net, Bowden explains, could “crack most codes, break into and plunder just about any protected database in the world, and potentially hobble or even destroy almost any computer network.”

Through interviews with members of the Cabal, as well as access to the archives of their private Listserv, Bowden reconstructs, in breathless prose, the months-long battle with the worm. The loose federation of virtual warriors included one of Microsoft’s top security experts, a graduate student, several Internet entrepreneurs, and a Bergen County, New Jersey, employee who fought botnets in his spare time. They mostly knew each other already, at least virtually, and began to compare notes as they watched the worm spread. Together, this gang of volunteers—or to put it in Bowden’s overwrought terms, “the Anointed, the Guardians, the Special Ones … capable of seeing the threat that no one else could see”—began looking for ways to stop the worm.

The Cabal blocked the botnet from contacting its master for months, but Conficker’s designer was watching them, and the worm continued to evolve. The domain names it generated daily to contact its programmer jumped from 250 to 50,000. It became capable of communicating from computer to com- puter, rather than domain to computer, so the bot- master had to tell only one computer what to do, and the word would spread. It soon grew too big for the Cabal to stop. Two months after Conficker’s debut, it had infected an estimated 8.9 million computers worldwide, including the Ministry of Defence and Parliament in the United Kingdom and military networks in France and Germany.

Bowden does his valiant best to make this material come alive. Metaphors and similes roll across the pages: Porras, the malware monitor, is “like a rancher with his boots propped on the rail on the front porch before a wide-open prairie with, as the country song says, miles of lonesome in every direction.” An infected computer is like Star Trek’s starship Enterprise with an “enemy infiltrator.” Or it’s a chef who gets distracted from a recipe by a demanding customer.

But in the end, this is a static story about men sitting by themselves in front of computers trying to prevent an invisible disaster with unknown consequences. And Bowden knows it. “The problem was,” he writes, “the nature of the thing. The threat was all potential.” On April 1, 2009, the most sophisticated strain of the worm was scheduled to receive its instructions. Here’s how Bowden describes the countdown to catastrophe: “The mighty botnet would wake up …

“and!!!

“and!!!

“!!!

“!!

“! …

nothing happened.” The threatened cyberpocalypse didn’t occur. The bad guys remain elusive. Indeed, although 16 young hackers were arrested in Ukraine for using Conficker to siphon $72 million from bank accounts, all the Cabal can surmise about the botmaster, likely more than one person, is that it has “a deep knowledge of Windows … an insider’s understanding of the computer security industry worldwide, as well as a high-level understanding of Internet traffic.” Readers who reveled in the very particular details of Bowden’s Black Hawk Down—the grit of the Mogadishu streets, the sharp perspective of Somali fighters, and the moment-by-moment dialogue of the besieged Rangers—will be disappointed.

As a book, Worm falls short. But as a wakeup call? Well, let’s just say that after reading it, I’m glad that the computer on which I typed this review didn’t come with Windows’ Port 445.