We’ll Always Have McSorley’s

How Joseph Mitchell's wonderful saloon became a sacred site for a certain literary pilgrim

When I was in college at the University of Kansas, my friend Harris and I made “pilgrimages” to towns we’d read about. Or to places in songs. One summer we drove my open-top CJ-5 ranch Jeep (with the windshield down when we cruised through cities large and small) from Lawrence, Kansas, to Bangor, Maine—all because of Roger Miller’s “King of the Road.”

On the way we stopped just shy of Bangor at Old Town, where we discovered a boat builder. After checking our pocket money and double-checking our bank balances, we bought a canoe and rigged it as a top for the Jeep so that we sailed along in shade. The canoe was red like the Jeep. People would honk and wave and flash their lights.

We were not tempted by Glen Campbell’s “Wichita Lineman.” Too nearby—especially if you drove the main roads. And there was no there on the way to Wichita unless you counted Hutchinson’s “world’s largest grain elevators”—which we did not. Even if William Inge and William Holden did.

After we were both out of graduate school, Harris and I once again headed out (same Jeep; windshield down through Salina, Hays, Atwood, Buffalo Gap; no canoe) for Scarborough Fair (which we thought was in northern California), only to get as far as Deadwood, South Dakota, and the graves of Bill Hickok and Calamity Jane, where we ran out of money. Later we learned that our destination was not only in the wrong country, but in the wrong century as well. Ours was a road not possible to be taken.

Before that misguided adventure, there was the semester Harris and I enrolled in an American literature class taught by a celebrated visiting multi-adjective New York University professor. Just before spring break, he observed that southern novels are “grotesque and gothic” and as such their details are exaggerated: “There is more Spanish moss and kudzu in Capote’s fiction than in fact,” he said.

Harris and I thought we’d find out for ourselves, so we drove to New Orleans (this time in Harris’s Daimler convertible, top down) where we discovered Spanish moss and kudzu in a plenitude that even Truman Capote had not imagined. Plus a streetcar named Desire. And a tavern called Ruby Red’s with a lovely Vargas girl framed on the wall behind the bar, and an equally lovely one tending the bar. Peanut shells on the floor. We were two days late getting back to campus. By then our professor had sailed on to Jack London’s Sea Wolf, where in “real life” men were “not that mean to one another.”

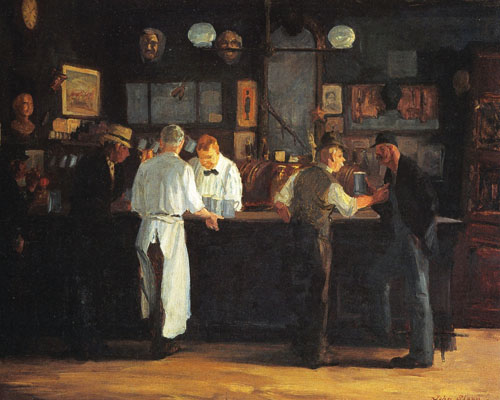

Detail of “McSorley’s Bar,” John Sloan, 1912 (Source: Detroit Institute of Arts)

Which brings me to this: one blue-blizzard winter night while studying for an American poetry exam, I discovered the following lines from an e. e. cummings poem that the editor of the anthology had titled “Snug and Warm Inside McSorley’s”: I was sitting in mcsorley’s. outside it was new york and beautifully snowing. It seemed like a good place to be with Whittier making coldness visible on the vast prairie just outside the frosted window of my barely heated (frugal landlady) garage apartment. Not that I knew where McSorley’s was—or what it was. At least it was snug and warm.

“It’s a bar,” said Lola, my girlfriend in those days. “In New York City.” Lola was an art history major. “Somebody from the Ashcan School made paintings of it. I’ll find them for you.”

“Let’s go,” Harris said a week later. We were at the Gaslight Tavern drinking red beers and looking at an art history book opened to John Sloan’s McSorley’s Bar. “We can leave after Christmas and be back when classes start.”

“You want to come along?” I asked Lola.

“If I’m going to make a pilgrimage—as you guys call them—to a bar, I’d rather go to the Folies Bergère and have champagne.” We didn’t know where that was either, but it probably wasn’t in Kansas.

“Besides,” she said, “I can’t get into McSorley’s.” She put a copy of Joseph Mitchell’s McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon on the table with her art history book and our beers.

“Why not?” Harris asked.

“No women allowed,” she said, opening Mitchell’s book to the first chapter. “Read it yourself.”

“Where’d you get it?” I asked.

“The Abington,” she said.

The Abington Bookstore was next to the Gaslight Tavern, and sometimes after lunch we’d go over and wish we’d spent less money on red beers so that we could buy the used books the owner, John Fowler, had for sale. Until he opened his store, the only used books we knew about were in the library.

“It’s autographed,” I said, looking at the title page. I had never seen an autographed book before.

“It’s your Christmas present,” she said. “When you get to McSorley’s, write me a letter. I want to know if it’s still the way Mitchell describes it. And if it looks like Sloan’s painting. Especially if it looks like the painting. I’ll write you from Paris.”

Harris and I did not go to McSorley’s that winter break. But I remember putting Lola on a TWA triple-tailed Constellation to New York with a connecting overnight flight to Paris where she was to begin a semester-abroad program in art history. It was a blue-cold-blizzard-is-coming kind of prairie day. Not a trace of snugness to be found. She turned at the top of the boarding ramp and waved goodbye.

I’ve lost track of the 1960s. At least its chronology. It’s not a matter of Puff the Magic Dragon, but the decade seemed scrambled even as it was happening. No narrative; all abstract montage. Everything used. But not much signed. More than all the flowers gone. In my case: a book, a friend, a girlfriend. I never sent the letter I wrote—but then, neither did she.

The summer after the afternoon when I had been looking at John Sloan’s painting in the Gaslight Tavern, I am sitting in McSorley’s “Wonderful Saloon” on East Seventh Street just off Third Avenue in New York City—not far from The Cooper Union.

It is my first trip to Manhattan, and I have already discovered that the A-Train is more than track three on my Columbia Record Club LP; that there is a hospital with the same name as a lip-kissing, candle-burning American poet; that the White Horse Tavern has (not unlike our Gaslight Tavern) a used bookstore (more than one) close by; and that Henry James’s Washington Square is my Washington Square—at least mine because that summer I am living in an apartment facing the east side of it.

The NYU professor had been impressed by my essay about Capote’s Other Voices, Other Rooms (“required reading”), and especially impressed that I had compared it (unfavorably) with George Washington Cable’s The Grandissimes (not even listed as “suggested reading”). During my conference with him, he wondered if I might be willing to house-sit at his apartment during the summer while he went to Italy in search of Edith Wharton’s “Roman Fever.”

“It’s in the East Village,” he said. “Do you know the Village?” A village in a city didn’t make sense to me, but I said yes. What did I know? To paraphrase Montaigne 10 years before I was to read him.

Starting that June, I spent three months living on Washington Square and taking lunches at McSorley’s, where I watched the NYU students, the Irish cops, and the several cats come and go—all the while using my pocketknife to carve University of Kansas into the wooden table by the window on the right as you go in. Two dark ales for a dollar; a liverwurst sandwich with thick-sliced raw onions, rich mustard, saltless crackers, two dollars. Sure enough, men only.

At the bar there were postcards that McSorley’s would send for you. On the front was a picture of the front door (open) with a bald man sitting with his back to us in a chair on the left-hand side studying (I now imagine) the clientele. Two ale barrels converted to flowerpots flank the door. On the backside across the top were the words: Since 1854 this famous Old Ale House has been known for its fine home-cooked food and excellent Ale served to a world-wide male clientele. Across the bottom: P.S. Meet me in McSorley’s. It is what I would circle with each postcard I wrote to Harris and Lola.

[adblock-left-01]

Because it was summer, outside it was beautifully snowing would have to wait: the promise I’ve made to return one winter night to live inside the language of the poem has by now become a mantra: sitting in the din thinking drinking the ale, which never lets you grow old blinking at the low ceiling.

At that table by the window with the sunlight coming in off Seventh Street, I’d read and reread Joseph Mitchell’s book to find what was in the prose that was still on the walls—and to learn (not that I knew it then) how you write with clarity.

Behind the bar was a large copy of John Sloan’s McSorley’s Bar. The waiters were in white aprons, both in and out of the painting. Men were talking in twos and threes toward the door where I am sitting, reading, eating, and carving. The back room is where Mitchell puts it: “(Old John [McSorley] believed it impossible for men to drink with tranquillity in the presence of women; there is a fine back room in the saloon, but for many years a sign was nailed on the street door, saying, ‘NOTICE: NO BACK ROOM IN HERE FOR LADIES’).”

Every now and then I’d look outside onto Seventh Street for Lola. In my mind’s eye, she would find me (how or why was never in the plot of the story I was writing in my head), and I would watch her for a moment from inside as she would double-check the address on the postcard, then look up to see if the card’s picture matched the front of the bar—ale barrels and all.

I would surprise her by coming out onto the street where through the open door we’d look at the Sloan and the cats and the men leaning their chairs on two legs against the wall. Then we’d walk over to the White Horse where women were allowed and where I had taught the bartender how to make a red beer. By August I understood how you can have a village in a city.

That summer I got so I knew the names of the streets around where I lived: Hudson, MacDougal, Thompson, Bleecker, and in walking them, I made a map of the Village in my mind’s eye. Most of the time I would walk in the mornings when it was cool. In the afternoons I would either go back to the apartment or find a movie. Once I saw Picnic, with Kim Novak trying to get herself out of Hutchinson, Kansas. It was as if I were being followed.

In the evenings I would usually make myself a meal from a deli I liked near Cooper Union, then go out again, at times stopping by the jazz clubs as the music spilled into the streets. There were days when I would take long walks uptown, and in this way I ran into the environs of the Woody Allen movies that would come into my life later. And other movies as well—now all famous in my mind: in Midnight Cowboy, the scenes off Central Park and those with Ratso and Joe Buck deep in the Bowery, below where I was living. And in Arthur Laurents’s The Way We Were, there is that plea from Barbra Streisand to Robert Redford not to go back to his lover on Beekman Place. By the time I saw the movie, I had been there. Over the years I have had the sense that the city—especially the Village—has been making multiple pilgrimages in my direction. The transmigration of treks.

Some days I would walk to the West Village and take my lunch at the White Horse Tavern. When I did, I’d lick the thumb of my right hand, punch it into the palm of my left hand, turn my fist around and pound it into the palm on the spot where I had put my thumb. It is what we do in Kansas to seal the good luck you have for seeing a white horse in a pasture as you drive along—say in a red ranch Jeep—canoe or not. If you’re with your girlfriend, you get a kiss. Even at the White Horse, I kept looking.

I was trying to be a writer. I had my portable Remington; the professor said I could use the kitchen table as my desk. To warm up, each day I’d add to my letter to Lola, typing on the small sheets of yellow sketchpad paper she had given me. After a paragraph or two, I would put what I had written into Mitchell’s McSorley’s as a sort of bookmark. Then I’d begin my own work—a novel set on the western high plains of Kansas into which I stuffed as many grotesque details (coyote hunters bringing into town bundles of ears, each attached by a strip of skin, to claim the bounty at the county office) and as much profanity (“He’s lower than snake shit at the bottom of a post hole”) as the prose could carry in hopes that one day a famous multi-adjective professor would lecture that western Kansas cannot be all that bizarre and profane. He, too, would be wrong. Neither the novel nor the letter was ever finished.

In Joseph Mitchell’s McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon, there is this:

At midday McSorley’s is crowded. The afternoon is quiet. At six it fills up with men who work in the neighborhood. Most nights there are a few curiosity-seekers in the place. If they behave themselves and don’t ask too many questions, they are tolerated. The majority of them have learned about the saloon through John Sloan’s paintings. Between 1912 and 1930, Sloan did five paintings, filled with detail, of the saloon—“McSorley’s Bar,” which shows Bill [McSorley] presiding majestically over the tap and which hangs in the Detroit Institute of Arts; “McSorley’s Back Room,” a painting of an old workingman sitting at the window at dusk with his hands in his lap, his pewter mug on the table; “McSorley’s at Home,” which shows a group of argumentative old-timers around the stove; “McSorley’s Cats,” in which Bill is preparing to feed his drove of cats; and “McSorley’s, Saturday Night,” which was painted during prohibition and shows Bill passing out mugs to a crowd of rollicking customers. Every time one of these appears in an exhibition or in a newspaper or magazine, there is a rush of strangers to the saloon.

[adblock-right-01]

One night I walked down Thompson Street to the Village Gate at the corner of Bleecker. I had never gone in, but at times during the day when I passed by, I could hear music coming out of a basement apartment just below: sad, soulful music. A man playing his guitar.

The Village Gate was always busy with people going in and out—people who seemed to be at home there, as were Harris and I and Lola at the Gaslight. I’d stand on the sidewalk and listen to the music, sometimes leaning against a lamppost or a car fender while eating the pretzel I’d buy from a vendor I liked on Third Avenue. I wasn’t cheap; I was careful.

This one night, a guy about my age came out of the basement apartment below the Village Gate, saw me standing by the door, and said: “Come in. There’s a trio singing tonight. Two guys and a blonde.”

Over the years, what I have come to like about John Sloan’s painting is his use of chiaroscuro: the ability he has to make perspective (or depth) from a bit of darkness in the composition, a black figure set in contrast to light from a window in a back room, or the apron of a waiter, or the face of a woman wearing a bow. It is also what I have come to admire about Joseph Mitchell’s writing: the singular significance of small details that create a depth. Both are portrait painters. As was e. e. cummings.

Let no art history scholar from my past willfully misunderstand me: I know the lingua franca of the Renaissance cannot be transferred intact to the work of an American journalist—even an exceptional one like Joseph Mitchell. But in my mind’s eye, I am sitting in McSorley’s Old Ale House with both the words of Mitchell and the paintings of Sloan as friends, and I am looking past the coal stove into the back room where I see an old workingman sitting at the window at dusk with his hands in his lap, his pewter mug on the table. And he is snug and warm and outside it is New York.

Then one day I lost it. The book. The letter to Lola. It was a Sunday when I found it gone. It was not in the apartment. Maybe it would be in McSorley’s. Maybe on the bench where I’d sometimes sit in Washington Square and where, after I had paid my way into the Village Gate to hear the blonde and two guys sing, I saw the blonde reading the paper.

Maybe I’d put it down when I bought my pretzel over on Third Avenue. Or on the counter at the deli near Cooper Union. But in three days of looking and asking, it was in none of those places and more places than those. Not the White Horse Tavern either, no matter how many times I poked my thumb into the palm of my hand and thumped it while telling the Deity of Lost and Found that I’d trade a kiss for a book. No.

The ranch in Kansas where I worked part-time to put myself through school (and then later as well) had a large pond on which I had put the canoe. The summer I was in the Village, a tornado came through, and while it did not do much damage to the houses and barns in the ranch yard, it tore up a duck blind we had built on the pond and lifted the canoe and sent it sailing across two sections to the ranch just east of us. There it stayed for a number of years—not found by the rancher (or by us, as we didn’t think to search that far)—until one summer we lost a few heifers, and I drove the Jeep over to look for them in our neighbor’s pasture.

Part of the canoe (the stern?) was broken up against the base of an old windmill with bits and pieces in the bottom of the abandoned tank. From there I could see in the pasture other parts (a cane seat, strips of canvas, ribs as if from a dead calf you sometimes find in draws when they’ve not made it through the winter) all scattered “abouts,” and “hereabouts”—as we say in that country. Together you would not have taken it to be a canoe, and maybe that is why our neighbor never called us about it. Besides, how many ranch hands have a canoe?

I mention this because before Lola flew off on that “coldness visible” day for New York and Paris, I told her I’d take her for a ride in the canoe when she came back. We’d mosey along with me paddling, not going anywhere but in slow circles, talking around the pond. It would be a fine late-summer day. After a while we’d have lunch on the bank with a bottle of French wine she’d brought back. A prairie boating-party lunch, now that I know what that might look like. Doves in and out of the cottonwoods on the dam. The night would stay warm, even after the butane light of the ranch yard came on, and we’d talk: She would tell me about Paris and the Folies Bergère, and I would tell her about New York and McSorley’s. And how one day I would show her the Village on our way to her showing me Paris. Stars falling out of the August sky.

The copy of McSorley’s Wonderful Saloon I have now is a used Pantheon hardback edition with a dust-jacket photograph of McSorley’s in a sepia tone on the front. The photograph takes in not only the front of McSorley’s (ale barrels, door closed, no snow) but also the tenement above it where the various owners of the saloon have lived. On the back of the dust jacket there is a picture of Joseph Mitchell: bald, chin in the palm of his right hand, wristwatch, no rings, left arm over two thick books, tweed jacket, large eyeglasses. I had never seen a picture of him until this one. He does not look like I thought he would. The book is not autographed.

I write you now that I could not wait for the canoe ride to tell you about New York and McSorley’s, and so in my letter I had written some of what I have written here, and more: about who else I heard that night at the Village Gate; about how I discovered that Sloan had made a painting called Yeats at Petitpas, and how I thought on your way back to school from Paris I would show you where the painting might have been made and tell you that the Yeats in the painting was not the poet we studied in our English courses, but his father; about going into the New York Public Library, past the lions, to find myself where I would one day find George Peppard and Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s and—now that I think of it—where I did not check to see if that is where I had left your McSorley’s; about how I walked up Fifth Avenue and then through Central Park looking for Holden Caulfield’s ducks and back down the Upper East Side looking for the apartment where Zooey was in the bathtub, and Franny was on the couch with her cat, and Bessie was there, and thereabouts. And how I knew about Franny and Zooey because I had bought the book that summer and read it in the park on the bench where the blonde singer would read the paper on Sunday mornings—and once when she was at one end of the bench and I was at the other end. Not all is lost.

But it is also true that in that letter I did not tell you how I drove my Jeep to New York at the start of that summer, or where I parked it, or how at the end of the summer I drove it up Park Avenue early one Sunday morning and across the George Washington Bridge and asked the man at the tollbooth which was the road to Kansas, and he pointed straight ahead and then put a curve into his arm to the west. But it was what he said about the color of the road at the end of his gesture that made us both laugh.

And you do not know that when I got back to the ranch and went down to the pond to see that the canoe was gone, that the paddles were still there floating on the water with the cottonwood leaves just then starting to fall. Nor do you know how I learned why Harris did not answer my postcards.

Lola, there is more that I have not written both in your lost letter and in this; there is more I could write here and now. Yes, there is. But instead, how about—absent a canoe ride—we meet one winter day, snug and warm, inside McSorley’s, at a table on the right by the window as you go in, you looking up to see if you’ve got the correct place, maybe holding, after all these years, one of the postcards I sent you.

Times have changed: you have been to Paris (and so have I); these days we can both have two dark ales and look at the Sloan, the cats, the men leaning their chairs on two legs against the wall, the chiaroscuro of the back room. We can order liverwurst and onion sandwiches and talk about what we think has changed in McSorley’s from what Joseph Mitchell wrote—and especially from what John Sloan painted. I will tell you what has not changed between us. Outside it will be beautifully snowing.