There was a time, before our son was born, when hardly a summer would pass without our taking in a classical music festival. We often went to Tanglewood, where the music was as much of a draw as the idyllic countryside of the Berkshires, though sometimes we veered off to Caramoor, in Katonah, New York, or Glimmerglass in Cooperstown. We were especially fond of the annual August festival at Bard College—we would make a long weekend of it, staying in the nearby village of Rhinebeck, attending concerts on Saturday nights and Sunday afternoons, and spending the rest of the time driving around the splendid Hudson Valley.

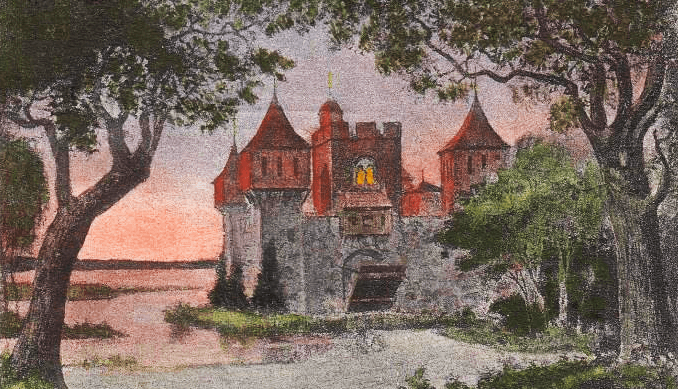

At Bard, each season’s concerts are devoted to a single composer, and in 1999, that composer was Arnold Schoenberg. The highlight of the festival was a performance of his lush, sprawling, early masterpiece of a cantata, Gurrelieder, begun in 1900 and completed a decade later. The work is based on a sequence of poems by the 19th-century Danish writer Jens Peter Jacobsen. Before Jacobsen wrote his own masterpiece, the novel Niels Lyhne (a favorite of Rilke’s and Mann’s and a book that has left a deep impression upon me, too), he produced a novella called A Cactus Blooms, at the end of which appear these “Songs of Gurre.” Here Jacobsen reimagines the legend of King Waldemar, who falls in love with the ravishing Tove and installs her at Gurre Castle, on the north coast of Denmark. When Waldemar’s wife, Queen Helwig, learns of this arrangement, she has Tove killed, sending Waldemar into a spiral of grief. So intense is his torment that he hurls curses at God and is subsequently fated to embark each night upon a wild hunt, accompanied by the ghostly figures of his vassals. In setting these “Songs of Gurre,” the 25-year-old Schoenberg employed a musical language that was opulent and rich, belonging to the late-Romantic world of Wagner, Strauss, and Alexander Zemlinsky. Yet his choice of text—with its erotic undercurrents and blatant blasphemy—was daring, suggesting the soul of the modernist that Schoenberg would soon become.

Gurrelieder has always been something of an obsession of mine, but in 1999, I had not yet seen it live. Indeed, performances of the work are all too rare. For one thing, its sheer scale poses problems: enormous forces are required, including several vocal soloists, a speaker, various choral ensembles, and a massive orchestra, larger than any ensemble previously called for in Western music. Gurrelieder is a spectacle, an event, part epic symphony, part operatic showpiece, and I looked forward to the concert with anxious excitement. Yet on the Saturday of the performance, the warm August afternoon gave way to an evening of torrential rain. The storms were intense, so much so that we considered hunkering down at our inn for the night—even though it was only a 15-minute drive north to the Bard campus. It wasn’t just the dicey driving conditions that concerned us. Nowadays, festival performances are held in a striking Frank Gehry–designed hall, but back then, concerts took place outdoors, under a large tent. The prospect of tramping across that sodden expanse of lawn, in the driving rain, did not seem all that appealing, despite the promise of a musical spectacle.

We decided to go. The rain had diminished by the time we arrived, and in the dusk, everything seemed awakened by the storm, a sweet humid aroma clinging to the wet grass and trees. Inside the tent, the orchestra, chorus, and soloists had assembled, and just as the conductor, Leon Botstein, began the first notes of the prelude—that magical depiction of sunset over the Danish coastline, in which Schoenberg paints in musical notes the last flickers of daylight upon the stout walls of Gurre Castle—the rain stopped. The surging lines of the strings evoked a feeling of longing and drowsiness, and by the end of the prelude, with darkness and unease coloring the music, darkness was falling around us, too. I could not have imagined a more wondrous blending of setting and music, and this feeling was sustained for much of that night, as the clouds cleared and we could see the sheen of moonlight outside the tent, and we heard Waldemar’s first aria (“Now dusk mutes every sound on land and sea, / the scudding clouds have gathered close against the margin of the sky”) followed by Tove’s languid response (“O when the moonbeams softly glide / and peace and rest pervade the world”). When Waldemar bellowed, Ross! Mein Ross! (“Horse! My horse!”), urging his steed onward through the forest, when the tempestuous music swelled and swirled, I heard claps of thunder in the distance.

I once saw a concert version of the first act of Die Walküre, with James Conlon conducting the National Symphony Orchestra, on a night so turbulent that I could still make out the wind from deep within the confines of the Kennedy Center Concert Hall—a wonderful effect, given that the piece takes place during a brutal storm, as Siegmund seeks shelter in the hut of Hunding the warrior. To experience music amid surroundings that contribute so directly to the experience must be a bit like reading Death in Venice on the Lido or “Tintern Abbey” while perched on the banks of the River Wye. At any rate, that performance of Gurrelieder so many Augusts ago came gloriously alive for me in a way that no recording—or few other live concerts, for that matter—ever could.

Listen to the prelude to Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder, with Seiji Ozawa conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra: