Last week I participated in a celebration of the 50th issue of The Harvard Review, a literary journal to which I have occasionally contributed. The dynamic editor of that excellent periodical, Christina Thompson, had conceived the idea of holding a public, three-way conversation between her, myself, and the fiction writer Lily King. I felt honored to be asked to represent the nonfiction side of the magazine, and glad to have an excuse to visit Harvard again (I had only been there twice before, and the university was still an intimidating mystery to me). I had steeled myself for a very low turnout, so I was pleasantly surprised when the parlor room on the first floor of Houghton Library, where the event would be taking place, was packed. Houghton Library is a smallish building compared to the majestic, world-famous Widener Library next door; it looked old and distinguished, though of indeterminate age (in fact it had been built in 1941 in a neoclassical vein), and I wondered aloud what it was known for. “Would you like a tour of the upstairs rooms?” I was asked. I said I certainly would, and was turned over to the director of scholarly and public programs, Anne-Marie Eze, who graciously showed us around.

On the second floor she took us into a suite of chambers, the Donald Hyde Rooms, which to my astonishment contained the largest collection extant devoted to Samuel Johnson and his circle, then a room with a large John Keats collection, next to a room dedicated to Emily Dickinson. The rooms had been decorated in a historically appropriate manner, with period furniture and elegant wood, the walls painted the same colors used by the British designer Robert Adam. “The plaster ceiling and the capitals of the pilasters, as well as the decorations in the Entry-Hall, are based on Adam drawings in Sir John Soane’s Museum, London,” stated the pamphlet we were given. In the large exhibit of Johnsoniana, four paintings of his various residences were inlaid into the ceiling. On the walls hung the famous portrait of him by John Opie, several pictures by Joshua Reynolds, and portraits of the actor David Garrick, Johnson’s wife, Tetty, his friend and patroness Hester Thrale Piozzi, and other figures connected to that circle.

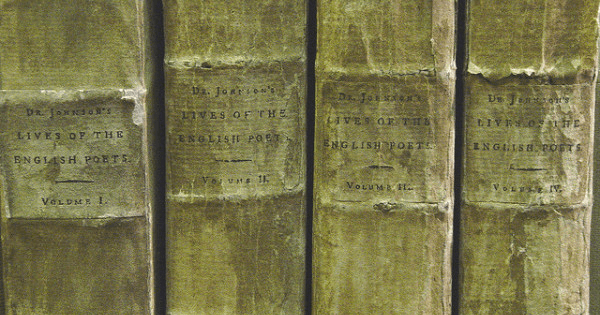

It just so happens that Dr. Johnson is one of my heroes, and I was tempted to fall to the ground before the massive glass-enclosed bookcases containing voluminous editions of his books, as well as his letters, manuscript drafts, and so on. To explain why he is such a hero of mine, I would start with his Lives of the Poets, that exemplary model of brief biography, his witty, sagacious essays in The Rambler, The Idler, and The Adventurer, his monumental one-man Dictionary. And then there is the man himself—as he comes down to us through James Boswell’s Life of Samuel Johnson and W. Jackson Bates’s superlative biography—who is so fascinating and endearing: his early struggles with poverty and depression, winning through to a stoical equilibrium infused with humor and largesse; his powerful mind and extensive learning; and perhaps most of all, his (unfashionable, today) commitment to wisdom and virtue, which made him a kind of Socrates figure. He was, to my mind, determinedly the grownup. His very sentences, with their symmetrical clauses, their gravitas, enacted a balanced perspective, refusing the enticements of neurotic exaggeration and romanticism. Those were William Hazlitt’s specialties, and while I cherish Hazlitt too, at this point in my life I’m more moved by the example of Johnson.

It was amusing to witness his large armchair, meant to hold his bulky body, and then visit the Emily Dickinson room, with its diminutive seat, and imagine them sitting side by side. Several authentic pieces that had been in her bedroom, including the very bureau that had held her poems, were in that upstairs room of the Houghton Library: their copies can be found in the Emily Dickinson house in Amherst, where people pay hundreds of dollars a night to commune with her, little realizing that they are communing with replicas and that the originals can be enjoyed for free at Harvard.

I would have dallied much longer in these rooms, but it was time to go downstairs and perform. Reluctantly I tore myself away, wishing that someday I could spend half a year or more exploring Dr. Johnson’s library. There is in me an incipient scholar-bookworm who would like nothing better than to pore through old manuscripts and letters, just for fun, without even trying to extract a product from that absorbing activity. Another road not taken.

Speaking of which, the next day I wandered through the campus, visiting the terrific Fogg Museum and watching young people crossing the quadrangle and trying to imagine what it would have been like to have gone to Harvard—how different I might have turned out. I would have been better-connected right after college graduation, and stuffier, perhaps, with that reserved air of self-satisfaction one often finds in Harvard alumni. There is something about Harvard that truthfully gives me the willies. All that wealth, and the gingerbread house/New England village stage set—it’s so damn attractive and yet feels so exclusionary to a Brooklyn ghetto kid like me. I know, I know, I was invited to speak there the night before, so I had no cause to feel so locked out of its hallowed halls like Jude the Obscure. If only they would let me inhabit a little corner of the Samuel Johnson Room in which to read and suck my thumb and ruminate, all grudges could be set aside.