Worlds Elsewhere: Journeys Around Shakespeare’s Globe by Andrew Dickson; Henry Holt, 512 pp., $35

It’s always refreshing when someone blows the dust off Shakespeare studies, and English journalist Andrew Dickson does it with gusto in his second book. His first was The Rough Guide to Shakespeare, part of a travel guide series that aimed (with reasonable success) to be both erudite and hip. Dickson strikes the same attitude in Worlds Elsewhere. He writes in breezy prose about his voyages across four continents to investigate how Shakespeare translates into other cultures, yet he also conveys some fairly dense information about the playwright’s role in the history of those cultures. His book will probably be loathed by Harold Bloom and other Bardolators who believe Shakespeare’s sacrosanct works should not be sullied by performance, let alone the kinds of extremely free adaptations Dickson enjoyed in his travels. Less reverential Shakespeareans will relish the author’s enthusiasm for Shakespeare’s global metamorphoses, while perhaps wishing Dickson could have assessed them in a more disciplined fashion.

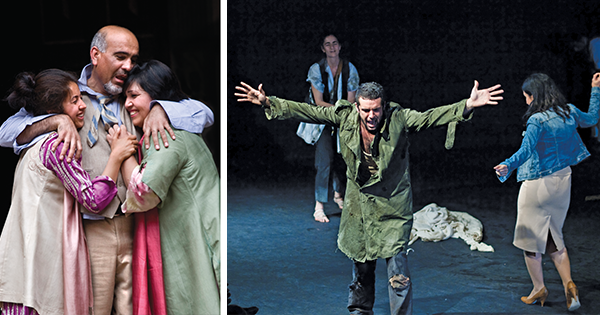

Mind you, Dickson’s freewheeling style suits his project’s originating impulse: the contrast he observed in the summer of 2012 between performances at the World Shakespeare Festival and Shakespeare as invoked in the opening ceremony for the London Olympic Games. You can almost see Dickson rolling his eyes as he describes “Maypolers cavorting on the greensward” and Kenneth Branagh “in waistcoat and stovepipe” declaiming a speech from The Tempest “to the swelling strains of Elgar’s ‘Nimrod.’ ” By contrast, The Comedy of Errors performed in Dari Persian opened his eyes to the rueful undercurrents in this rollicking farce, its themes of exile and separation all too familiar to the Afghan troupe presenting it. A Maori-language Troilus and Cressida “complete with strutting haka war dance” and King Lear reinterpreted as a sardonic folk tale by the Belarus Free Theatre were among the other World Shakespeare Festival productions that made Dickson realize “what I had often felt after a decade of watching British performances of Shakespeare: boredom. … There seemed to be something about being liberated from Shakespeare’s own language that allowed theatre-makers to approach his work with quizzical freshness.”

Anyone not reeling in horror at that last sentence is prepared at least to read with an open mind Dickson’s chronicle of a two-year excursion into diverse interpretations of Shakespeare in Germany, the United States, India, South Africa, and China. I had to take a deep breath myself, having written previously in these pages about the glories of Shakespeare’s English as spoken on the stage. Worlds Elsewhere reminds us how important the stories are, as Dickson catalogues people’s responses to many different plays in many different circumstances. Romeo and Juliet doesn’t seem foreign to audiences in India, where Bollywood movies glorify romantic love but arranged marriages are common and family ties paramount. Watching a student production of Julius Caesar in Johannesburg, Dickson was struck by the thought that a play about the struggle over how political power is exercised was particularly pertinent in postapartheid South Africa, “a country still grappling with the workings of democracy.” Richard III, a favorite of pre-Revolutionary Americans, portrayed “a tyrant fit for a rebellious population.” Hamlet, the brooding loner at odds with society and himself, became an icon of romantic sensibility thanks to Goethe and other German intellectuals, who felt such an affinity that they claimed the Bard as “our Shakespeare,” a boast that acquired ugly ramifications in the hands of Nazi propagandists.

Dickson’s text roves among cultural history, contemporary performance, social observation, and personal picaresque without much concern for narrative coherence. His research is impressive; tracing the centuries’ long history of each nation’s engagement with Shakespeare gives rich context to his vivid appreciations of present-day productions—even if you may wish he didn’t whipsaw between the two quite so casually and frequently. I certainly wished for fewer moments of self-indulgence, such as his list of American towns with Shakespeare-related names or his account of visiting the tangentially relevant Bollywood Bazaar. But I have to admit that Dickson’s informal style is part of his charm: it’s hard to resist an author who admits to getting tearful at Cymbeline—twice—or who says of a lurid poster for China’s “Salute Shakespeare” festival, “It looked as if Shakespeare had been assaulted by Andy Warhol while recovering from an LSD trip.”

Even more engaging is Dickson’s ardent championship of multiethnic, multilingual Shakespeare. The Winter’s Tale performed with Indian drums, song, and dance, the dialogue shifting from English at the Sicilian court to Hindustani in the Bohemian countryside, is in his persuasive view a legitimate refraction of Shakespeare’s much-vaunted universal appeal through the lens of local traditions and situations. As Dickson reminds us, Shakespeare himself blithely mixed genres. He lived in a cosmopolitan world of global exploration and trade—“his very language was alive with quickness and mutability, movement and change.” It’s this vibrant spirit, rather than the language in and of itself, that attracts artists and audiences around the world, even in former colonies with bitter memories of Shakespeare misused by their British overlords as one more example of white cultural superiority. And it’s not just nonnative speakers who find his English hard to understand, a fact acknowledged by the Oregon Shakespeare Festival last fall, when it announced it was commissioning 36 playwrights to “translate” Shakespeare into modern English.

Neither the OSF nor Dickson advocates doing away with Shakespeare in the original Elizabethan English; they simply suggest that there’s nothing wrong with other versions. The “contrasts and competing inflections” of global Shakespeare, Dickson argues, ring truer than ossified productions costumed in period garb and pronounced in plummy upper-crust accents. I would be heartbroken not to hear Hamlet as Shakespeare wrote it, but I’d love to see the Parsi-influenced Hindi movie, Wild West swashbuckler, and deconstructed postmodern Regietheater piece he defends as valid interpretations. I was moved and excited by Dickson’s celebration of “defiantly plural” Shakespeares, for all of his book’s meanderings and longueurs. Anyone who wants to keep the Bard’s plays alive in the 21st century should be glad to find him thriving in so many incarnations, “different at every turn.”