The Chief of Entertainers

Trumpet virtuoso Dizzy Gillespie was a jazz prophet, a musical genius, and a scatterbrained whirlwind

Dizzy Gillespie was hungry, restless, and in a playful mood when I arrived at his modest split-level ranch house in Englewood, New Jersey, one evening in May 1991. He suggested we head to the local pizzeria in his 1968 Mercedes, which he rarely got a chance to drive because he was never home for more than a few days at a time. At age 73, he was a man in perpetual motion, with a globe-girdling tour schedule.

While Dizzy devoured a large quattro stagioni pizza, he regaled me with stories of his month-long jazz tour of Africa in 1989. In Senegal, the House of Slaves museum, which memorializes a notorious “door of no return” for West Africans bound for the Americas, was closed when he dropped by for a visit one morning. But a Frenchman who lived in an adjacent building helped him sneak in by crawling through one of his windows. “Inside it looked like a bunch of animal stalls,” Dizzy said. “I could imagine my great-grandmother Nora locked up in there.” Nora, who was purchased as a house slave in the late 1850s by a plantation owner in Cheraw, South Carolina, was the daughter of a Yoruba tribal chief from what is now Nigeria. When Dizzy visited Nigeria later in the tour, he was treated like returning royalty. The king of the Iperu, a Yoruba tribe, gave him the title Baashere, which means Chief of Entertainers. “The Baashere of Iperu,” Dizzy said, savoring the sound of the words. “Ain’t that a bitch.”

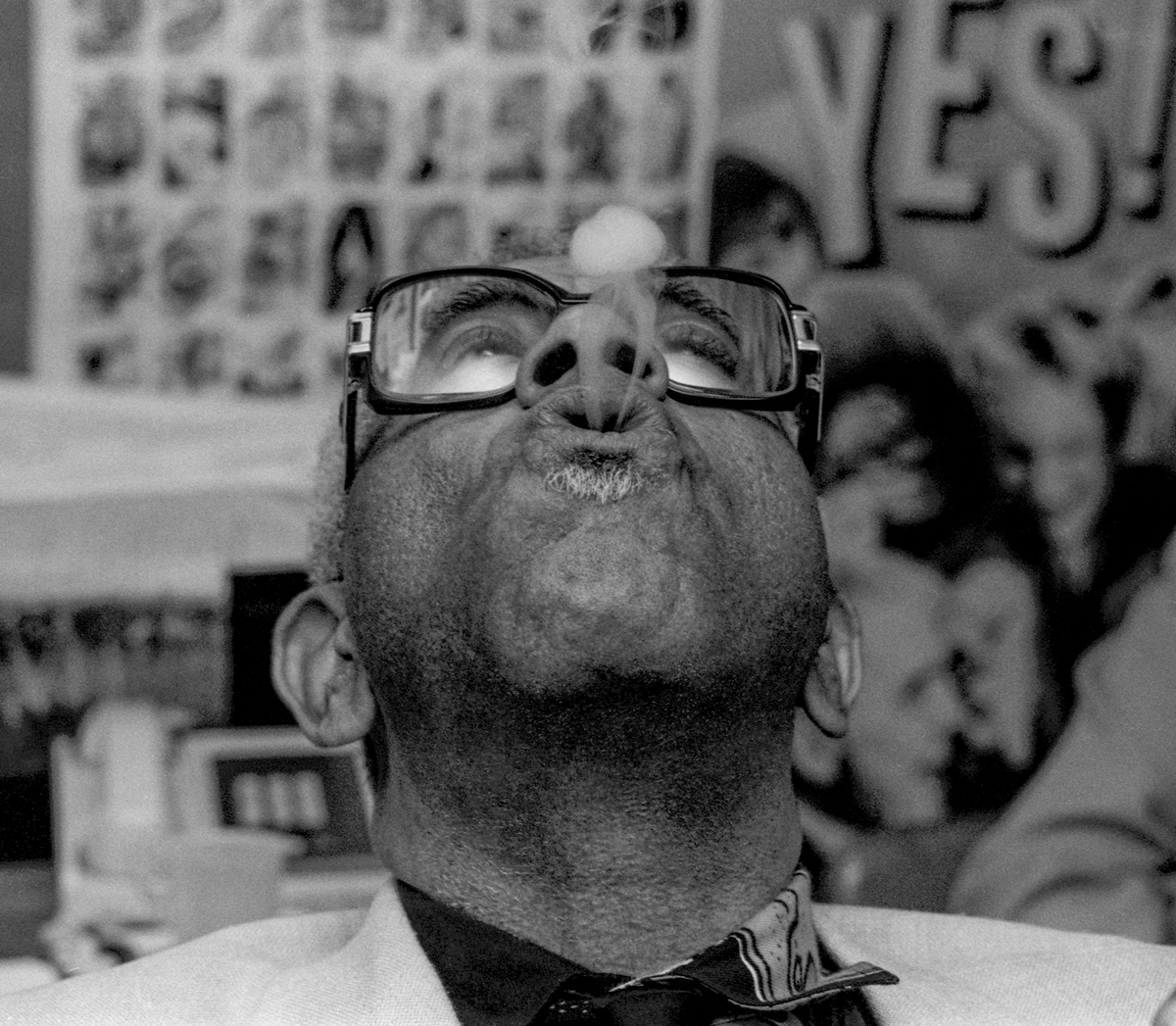

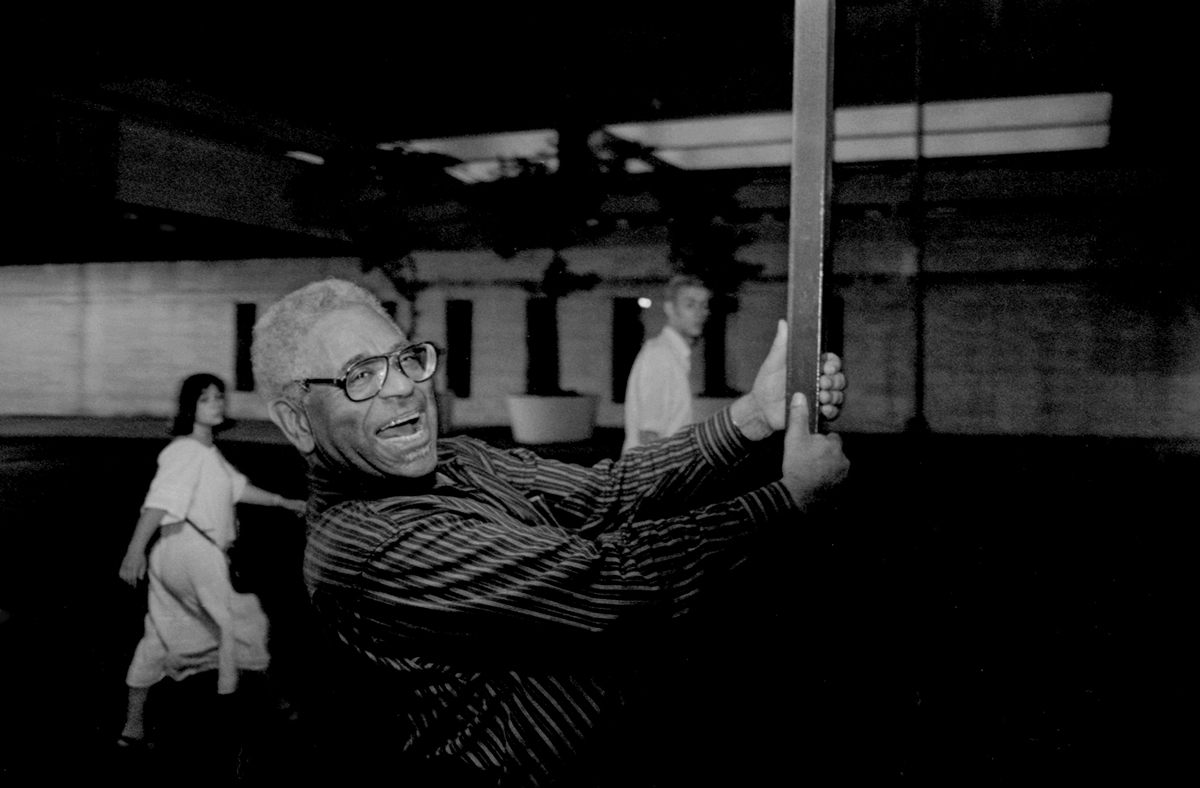

October 21, 2017, marked the 100th anniversary of the birth of John Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie. Dizzy was a consummate showman: a trumpet virtuoso with blowfish cheeks and horn bent heavenward who in his prime played faster and higher than anyone before or since. In the popular imagination, he was typecast as the steadfast sidekick to saxophonist Charlie “Bird” Parker, whose meteoric ascent into the jazz firmament and descent into heroin addiction fit the romantic archetype of an artistic genius doomed to die young. The late jazz critic Leonard Feather’s characterization of Dizzy as a “21st-century Gabriel” was more astute. Dizzy sounded a clarion call for the bebop revolution with his dazzling pyrotechnics on trumpet and harmonic innovations as a composer and arranger; expanded the ranks of the jazz vanguard by translating what Bird, Thelonious Monk, and other visionaries were doing into a language aspiring musical insurgents could understand; and then unleashed a host of ancestral spirits from the African diaspora by adding Afro-Cuban and Afro-Brazilian polyrhythms to the mix. He exuded a spirit of joy both on and off stage that reflected his faith in the disarming power of music and laughter to promote racial harmony and world peace, and he was unabashedly “dizzy,” a scatterbrained genius, full of boundless kinetic energy, who left a trail of madcap mayhem behind him.

Lightning crackled, followed by a loud thunderclap, as Dizzy and I left the pizzeria, and the rain came down in sheets. The ventilation system in the old Mercedes was on the fritz, so the windows fogged up. “Whooee,” Dizzy said as he ran up onto a sidewalk and then nonchalantly spun the car around on somebody’s front lawn.

My pulse was still racing when Dizzy steered the car into his garage. He whistled gleefully and led me upstairs to a cozy room where his clothes and papers were strewn haphazardly. “Welcome to the buzzard’s nest,” he said.

“Have you ever been frightened by anything?” I asked, as Dizzy settled into an easy chair.

“Scared? No, not too much.”

“But you’ve been in some pretty dangerous situations, right?”

“Well, yeah. Like playing a white dance in Biloxi, Mississippi, when you never know if somebody in the audience will decide they want to kick your ass. You’ve got to be ready for something like that. When Charlie Parker and I joined the Earl Hines band in 1942, everybody carried a piece. I had a little .38.”

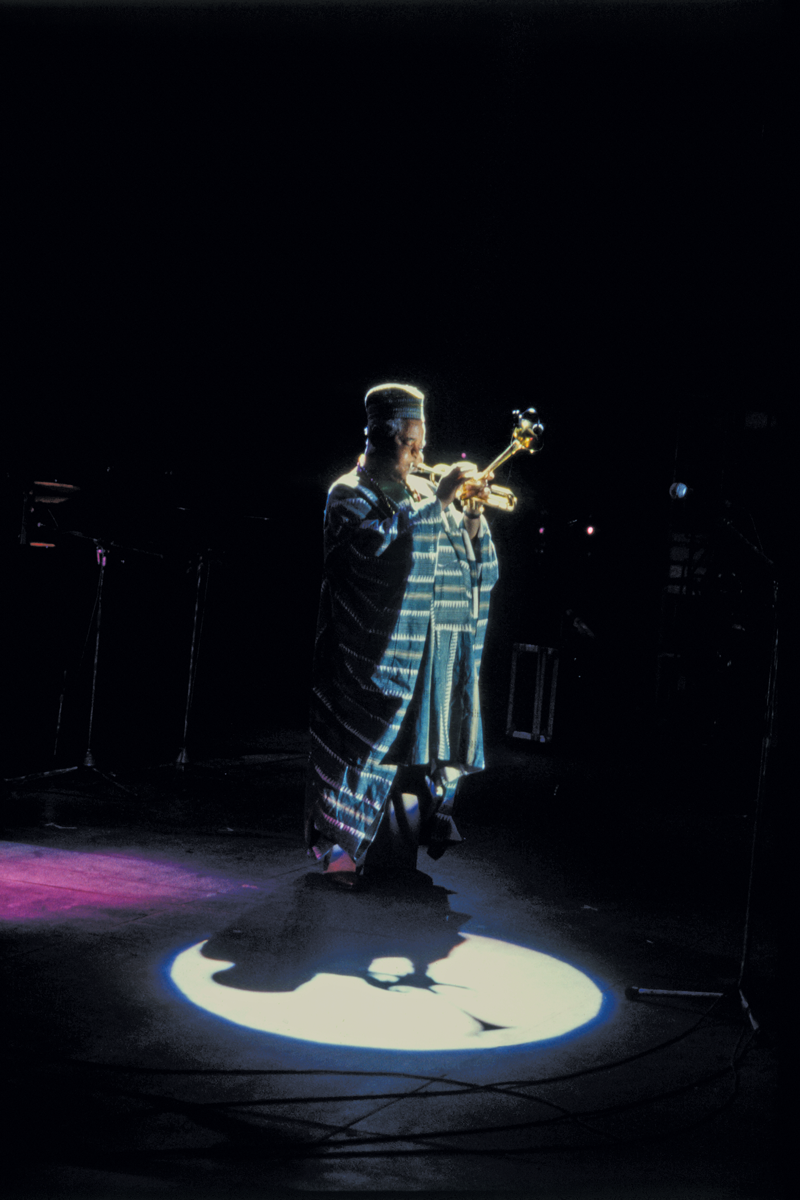

Later in the evening, Dizzy turned his TV on. Arsenio Hall was spouting some nonsense about “mutant fish” on his talk show. Dizzy shook his head. Earlier that spring, he had accepted an invitation to appear on the show and donned a ceremonial African robe for the occasion, as well as an elegant kufi cap embroidered “Baashere of Iperu.” He was annoyed that Hall didn’t bother to visit him backstage or find out much about him before the show. “He didn’t know what I represented,” Dizzy said.

After greeting Dizzy on air with some mindless chatter, Hall said: “What does your cap say?”

Dizzy paused for dramatic effect, raised his eyebrows and gave Hall a gentle lesson in deadpan humor and respect.

“It can’t speak.”

The audience cracked up.

For those who opened their hearts and minds to his music, Dizzy was a modern oracle.

“In traditional African societies, they say there are times when the creator sends down musical prophets to lift up our spirits,” says pianist Randy Weston. “Dizzy was one of those prophets.” In the late 1940s, Weston was helping his father run a soul food restaurant in their Brooklyn brownstone and met Dizzy around the corner at drummer Max Roach’s house, a favorite hangout for beboppers. What left the most indelible impression on Weston was seeing Dizzy onstage with his Afro-Cuban orchestra, which featured the conga player Chano Pozo. “During the slave era,” Weston says, “the African drum was outlawed in America because our ancestors still remembered how you talk with the drum. They could take a drum and send a message 20 miles away. When Dizzy had this jet-black Cuban propel his entire orchestra with one drum—bom de bop shoo bop shoo bam—that was a revolution.” Pozo’s style of percussion on “Manteca” and “Cubano Be/Cubano Bop” echoed the rhythms of Dizzy’s Yoruba ancestors. “The pulse of Mother Africa, which connects us as a global people, was at the heart of all his music,” says Weston.

Saxophonist Sonny Rollins was playing in a Harlem high school band when his idol, Coleman Hawkins, teamed with Dizzy in 1944 on “Disorder at the Border,” one of the first bebop tunes preserved on vinyl. Rollins met Dizzy around the same time during a jam session at an upper Harlem dance hall. “I was just beginning to mature as a player and Dizzy was like a god to me,” Rollins recalls. “He was on such a high celestial level. He looked down and said, ‘Sonny, you’ve got big feet.’ ”

Two parallel musical universes suddenly fell into perfect alignment for Argentine composer Lalo Schifrin when Dizzy showed up in Buenos Aires in July 1956 on a goodwill tour sponsored by the U.S. State Department. “That was several months after I graduated from the Paris Conservatory of Music, where I studied with the classical composer Olivier Messiaen,” Schifrin says. “And I’d put together a big band with the best Argentine jazz musicians when I returned to Buenos Aires.” During their weeklong concert stand, Dizzy and his fellow musicians attended a luncheon recital by Schifrin’s band. “As we finished, Dizzy headed toward the stage and said, ‘Who wrote these charts?’ ” Schifrin recalls. “I told him, ‘I did,’ and he said, ‘Would you like to come to the United States?’ I couldn’t believe it.”

A couple of years later, Schifrin arrived in New York bearing a surprise for Dizzy: “Gillespiana,” a five-part jazz suite. “I played a piano reduction of the composition for him and when he asked me how I imagined orchestrating it, I said, ‘Well, I’d like to have four trumpets, three trombones, five saxophones, four French horns, and one tuba.’ He flipped out.” Dizzy recorded the suite, and Schifrin served for several years as the pianist in his traveling quintet. In the meantime, Schifrin introduced the music of the Brazilian composer and singer Antonio Carlos Jobim to both Dizzy and Stan Getz, sparking the bossa nova craze in jazz.

“People didn’t recognize the full scope of Dizzy’s musical genius,” Schifrin says. “They thought he played too many notes. But like Mozart, he played exactly the notes he needed. He was a master of both harmony and melody. And no matter how fast he played, not one note was out of place.”

“He had an IQ of a million, but he couldn’t walk across a room without dropping something,” says Charles “Whale” Lake, who was Dizzy’s road manager for nearly a quarter century. “Every time we got into a limo to leave a hotel, I’d say, ‘Wait a second, John, I think I forgot something.’ Then I’d go back up to his room and find a trail of clothes, books, money, rolls of film, his passport. He was very unkempt.”

Dizzy was also full of childlike wonder. “He was very curious,” Lake recalls. “He wanted to find out every little thing. Whether it was a dance step or playing cards, he always wanted to know more.” Above all, Dizzy was curious about people, regardless of their cultural background or station in life, and spread goodwill everywhere he went through small acts of kindness. “He’d stop at a roadside stand on the way to the airport to buy a watermelon,” Lake says. “Then he’d give it to the flight attendants and ask them to cut it up for everyone on the plane.”

One evening, in his basement rec room, Dizzy gave me an impromptu lesson in rhythm. “White people clap their hands one two one two, but this goes one and two and one and two and,” he said. Then he began demonstrating a polyrhythmic pattern with his hands and feet while chanting, “Way down south in the land of cotton, old times there are not forgotten.” He chuckled as I struggled to match the dancelike movements of his limbs and keep a steady pulse by stomping on the downbeat with the heel of my right foot. “Whooee, our music is spiritually inspired,” he said.

Dizzy pointed to a bronze bust perched atop an antiquated stereo system, amid a jumble of pictures and other memorabilia. “Do you think it’s a good likeness?” he asked. In 1950, sculptor Dexter Jones captured a look of taut anticipation on Dizzy’s face that evokes the explosiveness of his music during that era. Jones also replicated a long thin crease in Dizzy’s upper lip created by years of blowing his horn, as well as a small indentation in the middle of his lower lip, a genetic inheritance from his father. Dizzy picked up the bust, rapped his knuckles on the hollow head and rotated it slowly, momentarily mesmerized by the semblance of his younger self. “From one angle it looks like I am about to shed a tear,” he said.

Dizzy grew up the youngest of nine children of James and Lottie Gillespie in a racist backwater of South Carolina. James, a brick mason in Cheraw who moonlighted as a pianist and manager of a ragtag local band, encouraged all the Gillespie kids except John Birks, an irrepressible mischief maker, to take up music. “Every Sunday after church, my father would get his razor strap and whup me, even if I hadn’t done anything wrong,” Dizzy recalled. In 1927, when he was 10, his father died of a severe asthma attack. “The first thing I did was to take that razor strap and cut it into a thousand pieces. Nobody used it after that.”

Five years later, a neighbor lent him a trumpet, and his natural affinity for the instrument earned him a scholarship at the Laurinburg Institute, an African-American prep school 28 miles from Cheraw. When Lottie moved to Philadelphia in 1935, he dropped out of school a few months shy of graduation to follow her. Armed with a pawnshop trumpet, which he carried in a paper bag, he soon landed a gig in a traveling band led by trombonist Frankie Fairfax. “Guys in the band joked about me being ‘that dizzy trumpet player from down south.’ The name stuck.”

A reservoir of simmering rage, which Dizzy had learned to keep a lid on as a youngster, added a whiff of danger to his demeanor and boiled over on one notable occasion early in his career. Dizzy got his first taste of commercial success in 1939 when he joined the Cab Calloway band. He was abruptly fired two years later when Calloway mistakenly accused him of throwing a spitball during a musical interlude by a small ensemble, the Cab Jivers. “Cab grabbed me by the collar and I had my knife out in a second,” Dizzy said. “I nicked him on his butt, and next thing you know there was blood all over his white suit.”

Losing the cushy gig freed Dizzy to spend more time playing with Charlie Parker, whom he’d met in Kansas City in 1940 while traveling with the Calloway band. “He was up in a hotel room playing ‘Sweet Georgia Brown,’ ” Dizzy recalled. “I’d never heard anything like the sound he got from that raggedy horn.” Over time they became soulmates, first in jam sessions in New York and later as musical co-conspirators in bands led by pianist Earl Hines and singer Billy Eckstine. Dizzy formed his own band in 1945 and included Bird in his front line. Their partnership culminated in an eight-week booking nearly a year later at Billy Berg’s in Hollywood. When Dizzy returned to New York, Bird lingered on the West Coast. “I gave him all his money and a ticket back, and what he did with it, God knows,” Dizzy recalled. “He suffered a nervous breakdown after that and went into Camarillo State Hospital.”

In 1947, Bird surprised Dizzy when he showed up at his first major concert at Car-negie Hall. “He walked out on stage with a rose,” Dizzy said. “It probably cost him his last 75 cents.” Even though the two teamed up for several historic concerts and recordings in the years that followed, Bird’s erratic behavior gradually tore them apart. Dizzy was forever haunted by his last encounter with Bird, a week before his death in March 1955. “I ran into him at a club called the Embers, on 52nd Street in New York, and he looked so sad. He said, ‘Save me.’ I said, ‘Man, nobody can save you. You have to save yourself.’ When I heard he died, it broke me up. I thought I would never get over it.”

Dizzy credited one person with making sure he didn’t get sucked into a vortex of self-destruction like Bird. “My wife, Lorraine, is my Rock of Gibraltar,” he said. When they met in 1937, paying gigs were scarce for Dizzy and she was a petite young widow earning subsistence wages as a member of a traveling troupe of chorus girls. Dizzy was attracted by her lissome beauty and wicked sense of humor, as well as her moral rectitude. “While the rest of the chorus girls were up in the wings looking for musicians who would take them to after-hours joints, she’d be down in the dressing room, knitting or crocheting or reading.” At first she ignored the mash notes Dizzy sent her. But their romance blossomed after she saw him begging outside the Apollo Theater in Harlem for 15 cents to buy a bowl a soup. Lorraine curbed Dizzy’s reckless spending, helped him negotiate with shady booking agents, and brought a sense of emotional stability to his life.

“She saved him from the dope and all the other stray things in the world of jazz,” says Jacques Muyal, a Swiss businessman and jazz producer who was one of Dizzy’s closest friends. Lorraine was also Dizzy’s secret muse. In a conversation with Muyal shortly after Dizzy’s death, she may have solved a mystery that has long obsessed jazz aficionados: the origin of the word bebop. “Lorraine said Dizzy liked to come to the Cotton Club rehearsals and the chorus girls sometimes practiced their dance steps without music, marking the rhythms by chanting be bop be bop.”

Over the years, Lorraine turned increasingly inward. She had a Catholic altar installed in a dedicated prayer room at the house in Englewood and kept what Dizzy described as “the cleanest residence in the world,” with plastic covers on the white furniture in the living room. On the rare occasions Dizzy was home, he slept in the buzzard’s nest and hung out with his friends and fellow musicians in the basement rec room, which was equipped with a piano, set of drums, and pool table. But he telephoned Lorraine daily from the road, and they would laugh about the latest developments in their favorite soap opera, As the World Turns. Shortly after they celebrated their golden wedding anniversary in 1990, I asked him to share his secret of matrimonial success. “Never tell your wife she is wrong,” he said. “If she’s wrong, she knows it. But she doesn’t want to hear it.”

Dizzy was a devoted but far from saintly spouse. Songwriter Connie Bryson met Dizzy in 1953, at age 16, when she and a young male friend queued up for tickets to see him perform at Birdland, a New York jazz club. “We were standing on the stairs leading down to the club and heard a commotion behind us,” says Bryson. “Dizzy was coming down the steps and all the women were asking for his autograph. He turned around, looked at me, and said, ‘Don’t you want my autograph?’ I said, ‘No, but you can have mine.’ ” Dizzy went over to talk with her later in the evening and was impressed when he learned her father was an eminent microbiologist and she had grown up listening to everything from Bach to Billie Holiday. During the next two years, Bryson showed up whenever Dizzy appeared at Birdland. “Nobody played like Dizzy. He broke the sound barrier,” she says. “My love of his music preceded my romantic feelings, but eventually I came to worship the man.”

They waited until Bryson was 18 before consummating the relationship. “We had unprotected sex on numerous occasions during the next couple of years because he had been told that he couldn’t have kids,” she says. Then she got pregnant. Their daughter, Jeanie, was a few days old when Dizzy saw her for the first time. “She was in a little bassinet, drawn up in a frog position and he said, ‘Where are her arms and legs?’ ” Bryson recalls. “I said, ‘Don’t worry. She’s perfect.’ ”

Jeanie’s first conscious memories stem from a cross-country bus trip she made at age four to Seattle, where she and her mother stayed with Dizzy and some other musicians in a stilt house. “I remember walking up the stairs and being a little scared, because they felt rickety,” Jeanie says. “And I remember being in a pool and watching Dizzy do a cannonball. When he jumped in, it looked like half the water in the pool came out.”

Bryson’s affair with Dizzy continued for several years while she struggled to raise Jeanie on a paltry income from a variety of temporary jobs. “The money I got from Dizzy was irregular, and only when I saw him in person,” she says. Everything changed after she pressed for steady child support and Lorraine found out about Jeanie. “All hell broke loose. Lorraine had to deal with three really hurtful things. One: I was 20 years younger than her. Two: I was white. But the real kicker: I had the baby. Dizzy later told me, ‘She never lets me forget it. She just sits in the house and doesn’t say anything.’ ” Dizzy formally agreed to make monthly child support payments of $125. Bryson’s relationship with Dizzy unraveled after that. “I never had any illusions that he and I were going to ride off into the sunset together,” she says. “But I was madly in love with this man, madly in love. And he loved Jeanie.”

Jeanie Bryson, who went on to become an accomplished jazz singer and released several critically acclaimed albums after Dizzy’s death, remembers with special fondness one rendezvous with her father when she was nine. “He came to our apartment to hear me play the flute,” she recalls. “Over one summer I had gone from saying ‘this is a flute’ to earning the first seat in the flute section in the school band, and I had just learned ‘The Age of Aquarius.’ He sat there listening with a grin on his face.”

In December 1966, Dizzy stumbled into the dawning of a new stage in his life. He and his band were in Milwaukee when he received a phone call from Beth McKenty. “I’d read the book Bird, in which Charlie Parker said, ‘Dizzy Gillespie is the other half of my heartbeat’ and those words stayed with me. So when I learned Mr. Gillespie was coming to town, I found out where he was staying and called him. I told him I was a member of the Baha’i faith and that I thought it was such a pity Charlie Parker died the way he did, because I felt he was just searching for meaning, searching for a way to get warm in the world. I told him my husband and I were coming to the show that night and would like to speak with him in person.” Dizzy was polite but noncommittal. “He said, ‘Listen, if there is anything I’ve learned on the road, it’s not to trust any man, woman, child, or beast.’ ”

Beth and her husband, Jack, sat through four long sets of music that evening with another Baha’i couple, sipping sodas and coffee. “Then around one in the morning, Dizzy said, ‘I don’t speak about my buddy Charlie Parker very often, but there is someone in the audience tonight who grasped what he was all about. So I’m going to dedicate the next set to her.’ ” Dizzy joined the McKentys at their table after the show and downed several double crème de menthes. “I thought he was going to vomit when our friends said Baha’is think being a person of color is a gift,” McKenty recalled. But he quickly bonded with Jack, a physician who specialized in urologic surgery. “He asked Jack a thousand medical questions and talked about friends who had died of various things. He said, ‘Life has been good to me. But I’ve hit everything a bit too hard on the road, and I don’t expect to live past 50.’ ” Dizzy had just turned 49.

The next time Dizzy was in the area, Jack scheduled him for a couple of days of medical tests. “They became buddies,” McKenty said. “Whenever he saw Jack later, he commended him for putting him back in harness.”

In the meantime, McKenty gave Dizzy some literature that piqued his curiosity about the Baha’i faith, which originated in mid-19th century Persia. The sect’s founder, Baha’u’llah, urged his followers to treat people of all nations, races, and creeds with respect and kindness. Baha’is look to a future when spiritual and political unification of the planet will occur through the wholehearted embrace of cultural diversity.

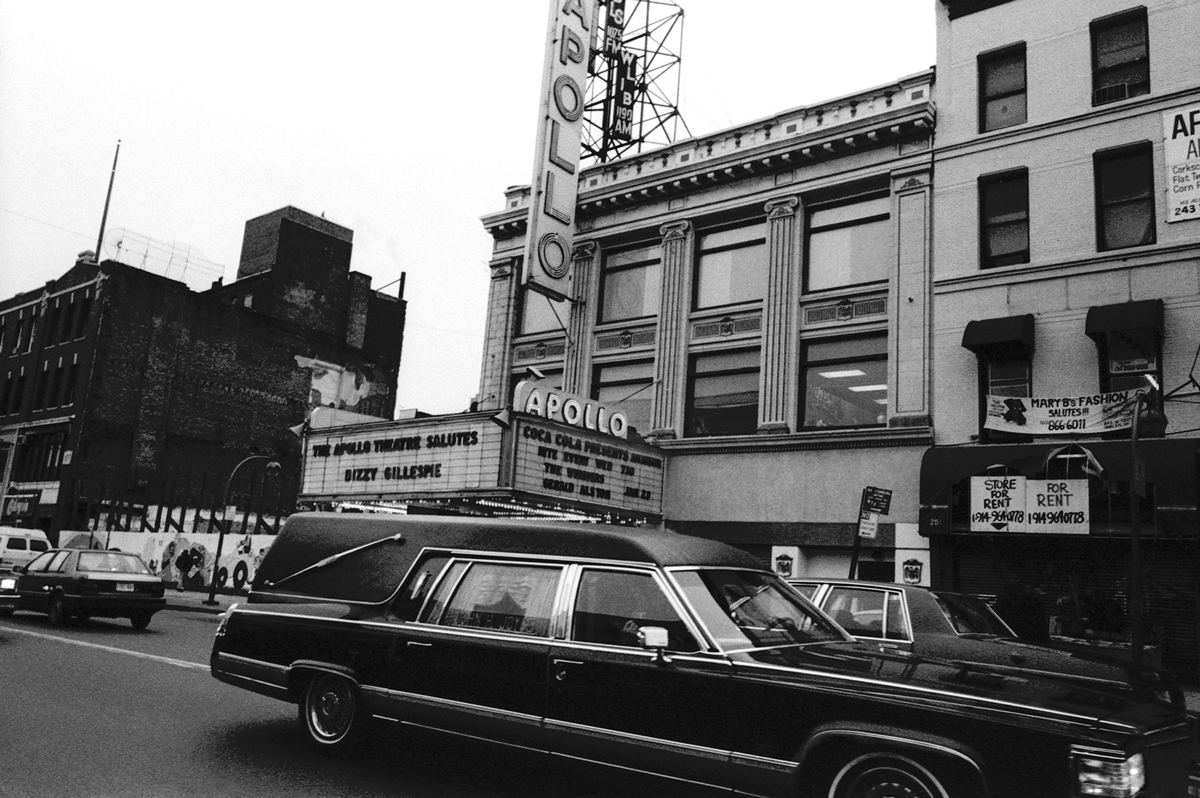

One day several months after Dizzy met the McKentys, he called Beth out of the blue, said a friend with a light plane had offered to take him to Kansas City to visit Parker’s grave, and invited her to come along. Even though Dizzy had organized a funeral procession and memorial concert in Harlem for Bird before his body was sent to Kansas City for burial in 1955, and helped pay for the interment, in the decade since he had never visited the gravesite.

McKenty brought attar of rose, a fragrant oil used in Baha’i rituals. She sprinkled it on Parker’s grave, and Dizzy recited the Baha’i prayer for mankind with her. “Then John Birks got out his trumpet and played the old spiritual ‘My Lord, What a Morning, When the Stars Began to Fall,’ ” she recalled. “It started to rain lightly. I felt as if we were almost in the next world and Charlie was with us, smiling.”

Dizzy made a formal declaration of faith a couple of months after he turned 50. But his acceptance of Baha’i standards of clean living was a Sisyphean struggle at first because of his insatiable thirst for alcohol. In April 1968, Dizzy and his quintet had a day to kill after making a special appearance at his old school, the Laurinburg Institute. So Dizzy borrowed the institute’s station wagon and set out to visit some of his childhood haunts in Cheraw with pianist Mike Longo. “Every place Dizzy took me we were given homemade wine, and soon we were feeling no pain,” says Longo. “A lot of black people in Cheraw were still living in shacks in the woods. Dizzy threw gravel on the tin roof of one shack and this old lady said, ‘John Birks, is that you?’ He said, ‘Yao-mm.’ She said, ‘Did you throw that gravel?’ He said, ‘No-mm.’ She said, ‘Was it that white boy with you?’ He said, ‘Yao-mm.’ ”

After a while, Dizzy decided he wanted to get some “creek”—corn whiskey—from an old moonshiner. Chaos ensued when the moonshiner told Dizzy not to give his young wife any creek and he poured her a full glass anyway. “The guy got out a pistol and started cleaning it, looking at Dizzy,” Longo says. “The woman was messed up and started yelling at Dizzy, ‘You think you’re a big star, but you ain’t shit.’ He pulled her wig off and she went berserk. She ripped Dizzy’s shirt and bit him on the shoulder. I grabbed Dizzy in a headlock to get him out of there. He threw up all over the car and passed out.”

As Longo hightailed it out of the woods, he was surprised to see state troopers out in force with their lights flashing. Amid all their drunken tomfoolery, he and Dizzy had missed the momentous news that evening: Martin Luther King Jr. was dead.

Dizzy’s quintet was scheduled to spend the next 10 days performing at Paschal’s Motor Inn, in a predominately black neighborhood in Atlanta. Stokely Carmichael,

H. Rap Brown, and other militants were using Paschal’s as their headquarters, and the surrounding streets were teeming with angry black people when Dizzy rolled up. “We were two hours late for the gig, and people were outside pacing,” Longo says. “They took one look at me and started rocking the bus.”

McKenty had worked with Martin Luther King Sr.’s wife, Alberta, on some interfaith projects, so when she heard about the assassination, she flew to Atlanta to help write thank-you notes to the thousands of people from around the world who had sent messages of condolence. When she learned Dizzy was also in town, they asked the King family for permission to visit the burial site as it was being dug. “While the grave workers took a coffee break, we stood over the open hole and said Baha’i prayers for the departed,” McKenty recalls. “Then John Birks got out his trumpet and played ‘Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen.’ ”

The next day Dizzy attended the regular Sunday service at Ebenezer Baptist, the King family’s church. “They motioned for him to come up into the choir in the middle of the service,” McKenty says. Again, “he played ‘My Lord, What a Morning, When the Stars Began to Fall.’ ” King was buried two days later.

In 1988, the governing council for the more than five million Baha’is scattered around the globe invited Dizzy to meet with them in the Baha’i World Centre on Mount Carmel in Haifa, Israel. He sat on an expansive rug in a cavernous rotunda while nine men gathered around him in tall chairs and said, “Tell us about the world.”

When Dizzy shared the story with me months later in a conversation about his faith that lasted into the early hours of the morning, he recalled being so nervous that he blurted out, “Y’all have got just about everything covered.” Baha’is believe every great faith is a link in a spiritual system progressively revealed by God to humanity. “Baha’i is the only religion which explicitly honors every other religion,” Dizzy said. “We believe that Moses, Zoroaster, Buddha, Jesus, and Mohammed were all bona fide messengers of God, and the main lesson coming down from all of these messengers is the unity of mankind.” Dizzy saw strong parallels between this doctrine of progressive revelation and jazz. He viewed himself as part of a chain of messengers and prophets, including Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Parker, who elevated people’s spirits with their music. “Jazz is a universal language,” he said.

In 1990, Dizzy led a Baha’i-inspired multicultural big band called the United Nation Orchestra on a “One World” tour of 24 European cities that included one-nighters in East Berlin, Moscow, and Prague. Before performing at a concert attended by 4,500 East and West Berliners, Dizzy made a pilgrimage to the Brandenburg Gate. “I climbed right up on top of that raggedy old Berlin Wall [which had come down the previous autumn] and threw rocks to the people standing down below,” Dizzy said. “It was wonderful seeing everyone look so jolly.”

I joined the tour for several days the next month. While waiting for Dizzy to board the bus for an eight-hour ride through the Swiss Alps from Freiburg to Verona, James Moody, who, at the age of 21, had first played with Dizzy in the late 1940s, said, “Every time I get on the bandstand with him is a musical lesson. Sometimes little bits of wisdom he imparts will come back to me years later, and I’ll say, ‘Ah!’ ”

By the time Dizzy arrived and headed to the back of the bus, several members of the band had already curled up on their seats and gone to sleep. Dizzy was bright-eyed and launched into a spirited discussion about firecrackers with a kindred musical polymath and comic spirit, Cuban saxophonist Paquito D’Rivera. “Two of my favorite artists are Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Dizzy Gillespie,” D’Rivera said. “Mozart was totally ‘out’ too. He was loco. That doesn’t mean the music isn’t serious. With Mozart and Dizzy, you can smile and be serious at the same time.”

Trumpeter Arturo Sandoval brought 200 cigars with him from Cuba as a gift for Dizzy, only to discover he had recently given up smoking them. “Fidel sent me a telegram and told me I should stop,” Dizzy said. Dizzy met D’Rivera and Sandoval when he visited Havana in 1977. Dizzy recognized a fellow virtuoso when Sandoval hit one high note after another at rapid tempos the first time they played together. “He once autographed a picture for me and wrote, ‘To my son. From your Daddy Dizzy,’ ” Sandoval said. “There is not enough room in one heart for the way that made me feel.”

As the bus neared Verona and the Roman arena where the band was scheduled to perform came into view, Sandoval played a few bars from a classical concerto by Leopold Mozart on a piccolo trumpet, an instrument rarely used by jazz musicians. D’Rivera shouted, “Hey, I think that place is even older than Dizzy Gillespie.” The venue was appropriate given the historic nature of the upcoming event, which featured Dizzy and the United Nation Orchestra on the same bill with groups led by two men who had also been close associates of Charlie Parker’s: drummer Max Roach and trumpeter Miles Davis.

Backstage before the show, Brazilian trumpeter Claudio Roditi showed Dizzy how he altered his intonation by changing his grip on the horn. “This guy is a real scientist when it comes to the trumpet,” said Dizzy, whose own technique defied scientific analysis. Dizzy’s cheeks puffed out shortly after he left the Cab Calloway band. “It must be what I had to do to make phrases like Charlie Parker,” said Dizzy. “A doctor told me I have vestigial gills.” A decade later, at a birthday party for Lorraine, a comedian fell on Dizzy’s trumpet, bending the bell upward. “I decided I liked the horn bent because I can hear my mistakes faster.”

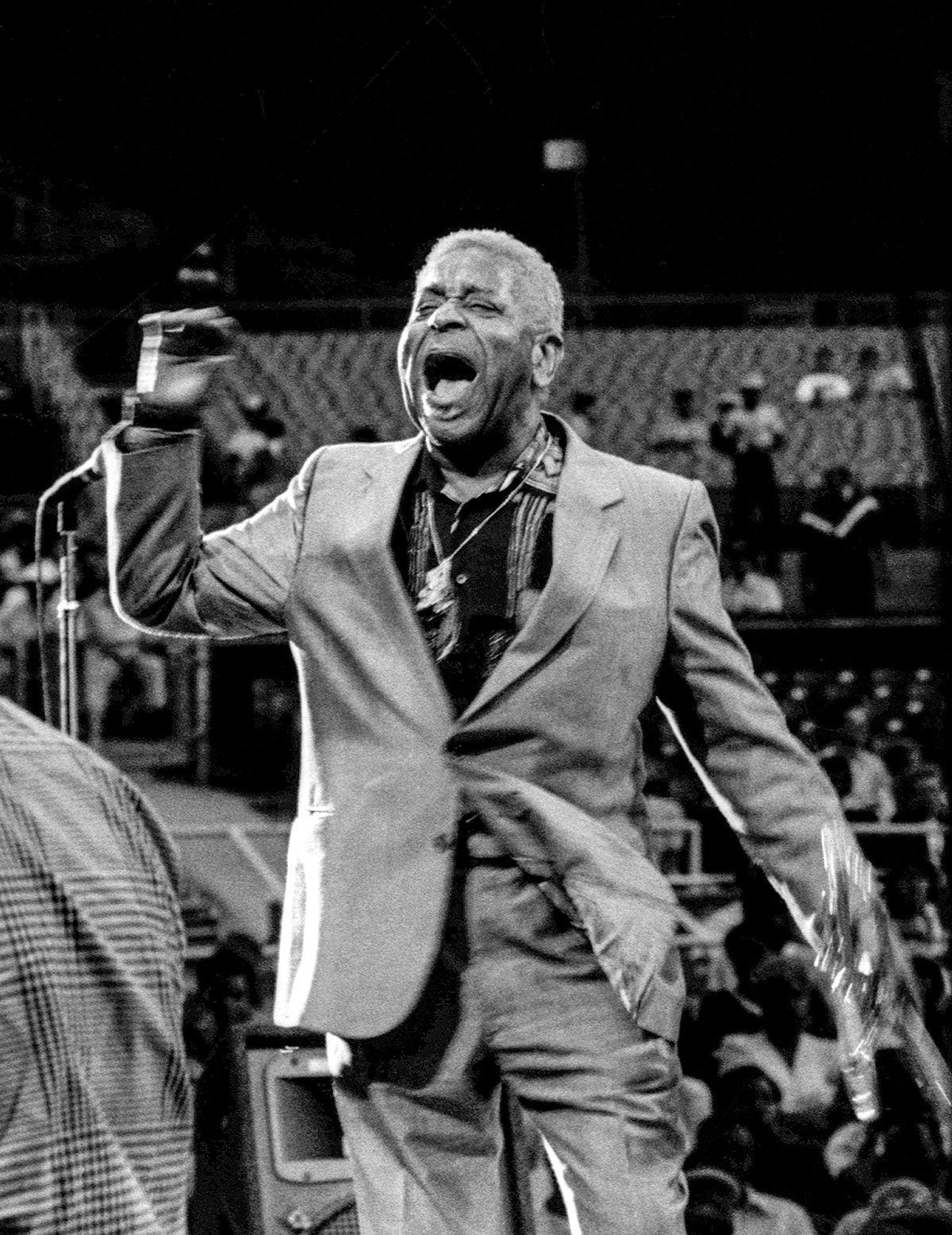

Dizzy took the stage before an exuberant crowd of 17,000 assembled in the open-air amphitheater. Brass harmonies resounded with the fullness and power of a squadron of Roman chariots, and the crosshatched rhythms laid down by the percussion section sizzled in the night air. Ninety minutes later, Dizzy took his last bow, and on the way out, he casually knocked on Davis’s dressing room door. Davis came to the door and grinned. They commiserated for a few minutes about the challenges aging trumpeters face keeping their mouths in shape to play, and the extensive dental work it entailed. Dizzy: “I busted some teeth eating some beans and rice.” Davis: “They’ve got mine held together with Krazy Glue.” Dizzy: “My jaw comes out. Makes it hard to hit some notes.” Davis: “You’ve got the biggest tongue in the world.” Dizzy: “My tongue has just got a lot of desire.”

The next morning over breakfast, Roach and Dizzy talked about the Miles mystique. “Miles has got this Greta Garbo-ish attitude,” Dizzy said. “He turns his back to the audience onstage and doesn’t want anybody to see him offstage. But he never acts funny around me.” Roach hadn’t seen Davis in 20 years and had hoped to hear him work some of his old musical magic. But Davis’s performance with his latest electric band left him shaking his head. “That motherfucker is looking like Halloween and sounding like April Fools’ Day,” Roach said. “I went up to him afterwards and said, ‘Miles, you fooled them again.’ ”

When Dizzy arrived for a black-tie State Department dinner hosted by Secretary of State James Baker in December 1990, the switchblade he’d carried since he was a young musician set off a metal detector alarm at the entrance. “Anytime I’m out with my clothes on I’ve got my knife,” he said. The event was a prelude to Dizzy’s receiving a Kennedy Center Honors Award for lifetime achievement in the performing arts.

The next June, in 1991, taking in a few breaths of muggy Manhattan air outside Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Hall after a jazz festival concert, Dizzy did a full-circle whirligig around a parking sign. A bystander, unaware that a limousine was already on the way, offered to hail a cab and asked, “Where are you going?”

“I think I’m going crazy,” Dizzy replied. “Then I’ll probably go completely bonkers.” As the bewildered bystander walked away, Dizzy suddenly turned serious. The news that civil rights champion Thurgood Marshall had just resigned from the Supreme Court had been troubling him all day. “He wants some peace of mind in his old age, and he deserves it. But where does that leave us?” Dizzy said. “It’s no longer Snow White, get back. Bigotry is now a nasty word, but you still have a lot of people who feel they are bigger and more important than anyone else in the world.

“I think I’ll send Justice Marshall a telegram and say, ‘Okay, you did it. Now I’ll die,’ ” Dizzy said. When he saw the troubled look on my face, he softened the explosive impact of his comment with a belly laugh and said: “The hard truth is, you can’t depend on anybody except yourself. And whatever happens, you have to just keep chugging along.”

In February 1992, Dizzy suffered severe nausea and elevated blood sugar levels during a West Coast tour with his quintet but refused to cancel any shows. By the time he returned home in March, his urine had turned orange. Doctors at Englewood Hospital found a cancerous growth in his pancreas and removed most of it during a six-hour operation.

When Dizzy left the hospital several weeks later, Lorraine’s nephew Gerald Glanville, a former New York cop, was his primary caretaker. “I was at the house 24/7 because Lorraine didn’t want any strangers staying overnight. It was difficult for Lorraine because she wasn’t used to having Dizzy around.” She also found it difficult to cope with the steady stream of visitors who showed up on her doorstep. “She was receptive to only a handful of people. When anyone else came to the house, she just vanished.”

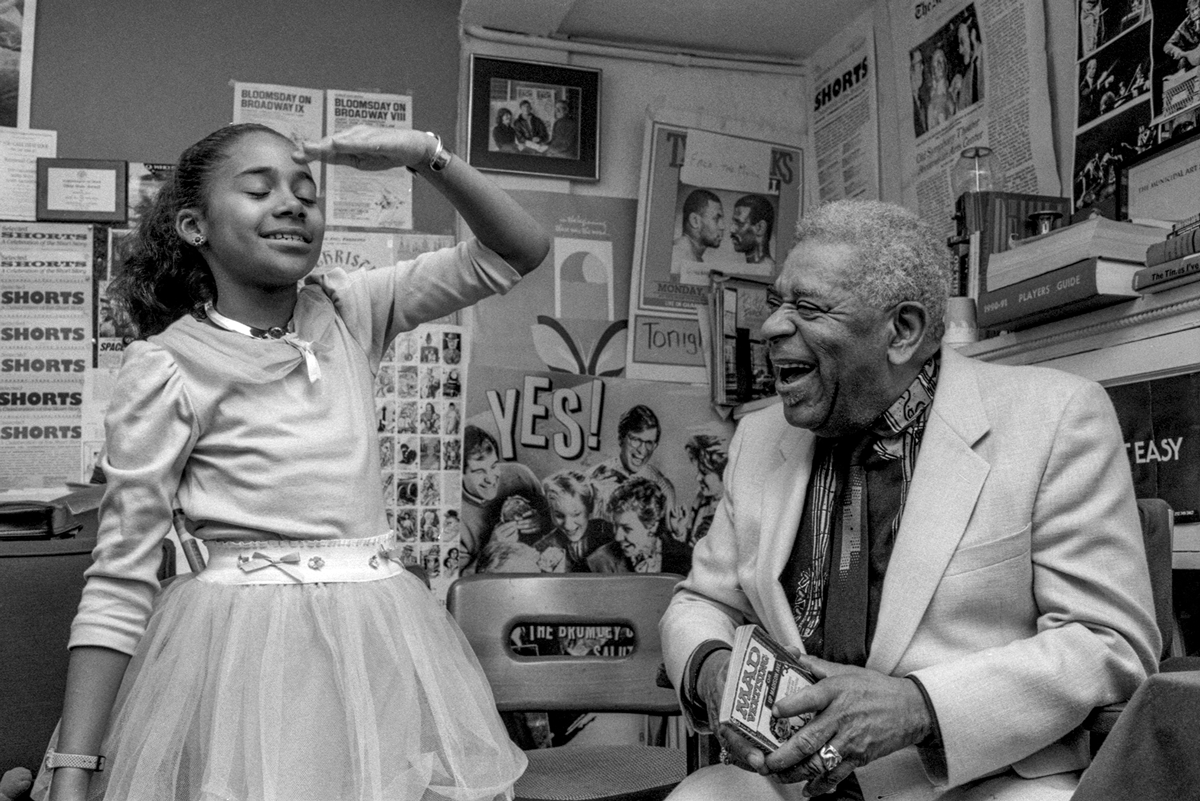

I took my daughter Raelyn, then five and a half, to see Dizzy in early May. He had stolen her heart—and mine—during the Kennedy Center Honors festivities by inviting her to join the small entourage that accompanied him in a stretch limo to the awards ceremony. At his house, we visited him on the patio. Raelyn was scared at first because his body had shriveled so much since she had last seen him. But he held his finger up to his lips and puffed out his cheeks to greet her. Then he took her by the hand and picked her up so that she could look inside a wooden birdhouse where a family of bluebirds had built a nest and deposited several eggs. When I called to chat with Dizzy a few days later, he asked me to put Raelyn on the line. The eggs had hatched and he held the portable phone next to the nesting box so that she could hear the baby birds chirping.

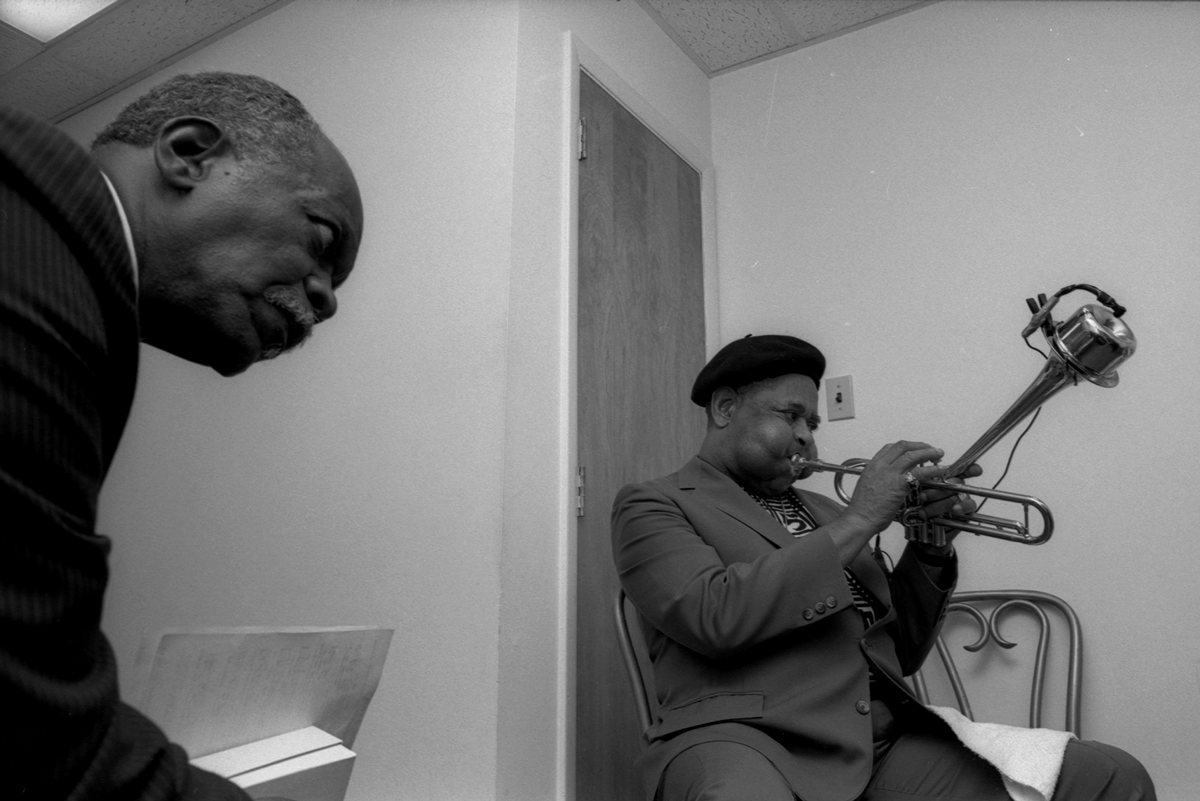

Dizzy was optimistic that he would get well enough to perform again. Mike Longo showed up a couple of times a week to play duets in the basement. Other musicians dropped by occasionally as well, including James Moody and vibraphonist Milt Jackson, who used his index fingers like vibe sticks to tap out melody lines on the piano. In late August, Dizzy flew out to California for an all-star concert in his honor at the Hollywood Bowl. He made a brief speech thanking everyone for attending and said he hoped his doctor would soon allow him to play in public.

In September, Dizzy had a second round of surgery to remove more cancerous tissue. Trumpeter Jon Faddis was crestfallen when he visited his beloved mentor after the surgery. In anticipation of Dizzy’s 75th birthday in late October, Faddis had sent out for an overhaul a trumpet he had originally given Dizzy on his 65th birthday. “Dizzy loved that horn. But when he picked it up and tried to play it, he couldn’t get a sound out. He didn’t have enough wind to blow out a birthday candle.”

Even in his weakened state, Dizzy remained full of restless energy. “He spent a lot of time in the back yard just walking around,” says Glanville. “He’d walk all the way around the perimeter of the yard, with his hand out, rippling the bushes.”

Dizzy was hospitalized again in late November, and his condition steadily deteriorated during the holiday season. During one visit, Faddis asked if there was anything special he wanted. “He said he would like to hear ‘The Christmas Song.’ So I called up WBGO, a jazz station in Newark, and asked them to play it on air. A half hour later, I watched Dizzy’s face light up as he lay there listening to Nat King Cole.”

When Longo and Moody visited Dizzy a few days after the New Year, he was awake but couldn’t speak. “He had a bunch of tubes in him and his arms were like pool sticks,” Longo recalls. “But as soon as we walked into the room, he put his finger on his lips and puffed his cheeks out. Then he grabbed my hand and started stroking it. I said, ‘Man, aren’t you taking this a little too far?’ He started laughing.” Dizzy slipped into a coma a few hours later. The next day, January 6, 1993, he took his last breath in the company of old friends: Moody, Faddis, Jacques Muyal, and his boyhood buddy John Motley.

Raelyn accompanied me to Dizzy’s private funeral service at New York City’s jazz church, Saint Peter’s, in midtown Manhattan. She was fidgety and craned her neck to look at the towering pipe organ as we sat toward the back of the modernist chapel and listened to poignant testimonials and musical tributes from Dizzy’s close friends. When we joined the line of mourners filing past the open casket, as Wynton Marsalis sounded a soulful lament on solo trumpet, she clutched my hand tightly and paused for a few seconds to gaze in puzzled wonderment at Dizzy’s body lying perfectly still.

After the funeral procession drove along 52nd Street, which was lined with jazz clubs when Dizzy and Bird launched the bebop revolution, it picked up speed as it wound through Harlem en route to Flushing Cemetery in Queens, which is also the final resting place of Louis Armstrong. Eventually, the motorcade began to break apart and our ramshackle Toyota Corolla was part of a small convoy of stragglers toward the rear. The nervous rush of adrenaline I felt as we blew through several red lights reminded me of that night a thunderstorm erupted while I was out for a ride with Dizzy in his old Mercedes. Amid the chaotic chorus of honking horns that accompanied the funeral procession through the streets of the city, I imagined Dizzy putting a little extra wiggle in his waggle as he watched over us—with a twinkle in his eyes and a mischievous grin.