“It was in August, 1889,” Theodore Dreiser tells us in the first paragraph of Sister Carrie, that 18-year-old Caroline Meeber, known to her family as “Sister Carrie,” boarded the afternoon train for Chicago with her “cheap imitation alligator skin satchel” and her “yellow leather snap purse” containing “four dollars in money.” American literature would never be the same again.

One hundred years after Carrie began her journey, the novel that tells her story remains one of the towering achievements of American fiction. The character whose fate is entwined with Carrie’s, Hurstwood, remains, to my mind, the most interesting portrait of a businessman in our literature.

You can see quite early in Sister Carrie that Dreiser brings something new to the American novel. You can see it in the way he introduces Drouet, the “drummer” who flirts with Carrie on the train ride to Chicago. Among “the most striking characteristics” of the salesman, Dreiser tells us, “Good clothes of course were the first essential, the things without which he was nothing. A strong physical nature actuated by a keen desire for the feminine was the next. A mind … actuated not by greed but an insatiable love of variable pleasure—woman—pleasure.”

But it is not merely the frankness that is new. Unlike the genteel novelists who preceded him, Dreiser understands work. We see this when Carrie’s sister Minnie meets her at the train—”Her sister carried with her much of the grimness of shift and toil”—and we see it when Carrie steps into Minnie’s apartment: “She felt the drag of a lean and narrow life.”

We see it again when, in Chicago, Carrie gets a job making shoes in a sweatshop. Dreiser did not merely understand work; he understood it in his bones, the way a worker understands it: “The stool she sat on was without a back or footrest and she began to feel uncomfortable. … She twisted and turned … Her hands began to ache at the wrists and then in the fingers, and toward the last she seemed one mass of dull complaining muscles.”

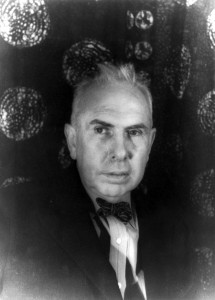

Dreiser, the literary historian F. O. Matthiessen once remarked, was the first American novelist from “across the tracks.” The son a German-American immigrant and a woman of Pennsylvania German descent, he was born on this date in Terre Haute, Indiana, in 1871, the next to last of 10 children.

The family was miserably poor. One of Dreiser’s sisters, the model for Sister Carrie, eloped with an older man who financed their flight by stealing money from his employer. A brother, Paul, ran off with a minstrel troop, changed his last name to Dresser, and won a measure of scandalous fame as the composer of a song about his mistress, the madam of a brothel, “My Gal Sal.”

Theodore left home at 16, worked in a warehouse, spent one year at Indiana University, worked as a real estate clerk and a collections agent in Chicago, and then worked as a newspaperman in Chicago, St. Louis, Toledo, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and New York City.

He was 28 years old when, in 1899, a friend convinced him to try his hand at fiction. Published in the fall of 1900, Sister Carrie sold 456 copies and earned royalties of $68.40.

Nowadays, it’s hard to find anyone under the age of 50 who has read Dreiser, even though he, Faulkner, and Saul Bellow were, to my mind, the most powerful American novelists of the 20th century.

In business, Chicago in the last years of the 19th century was the city of the meat packers Philip Armour and Gustavus Swift, the railway-car-maker George Pullman, the hotelman Potter Palmer, the streetcar tycoon Charles Yerkes (later the subject of Dreiser’s Cowperwood trilogy), the electric company czar Samuel Insull, the department-store magnate Marshall Field, and the mail-order pioneers Richard Sears, A. C. Roebuck, Julius Rosenwald, and Montgomery Ward.

To visit this Chicago, you need only open Sister Carrie: “Already vast net-works of tracks … stretched on either hand. … At the sides of this traffic stream stood dingy houses, smoky mills, tall elevators. … Gatemen toiled at wooden arms which closed the streets. Bells clanged, the rails clacked, whistles sounded afar off.”

Drouet, the genial salesman, is the first businessman we meet. Perhaps the best way to understand him is as a precursor of Willy Loman—Willy before his smile fails him. One of Willy’s maxims, ”Personality always wins the day,” might be Drouet’s motto.

As is often the case with salesmen, Drouet’s specialty is selling himself. Patter and personality are the tools of his trade. Dreiser captures him perfectly: “He bobbed about among men, a veritable bundle of enthusiasm. … He was one who would remain thus young in spirit until he was dead.”

Drouet’s shallowness makes for a telling contrast when Dreiser introduces Hurstwood, a man with “a good stout constitution, an active manner, and a solid substantial air.” We know at once that Drouet will not be able to hold on to Carrie against this rival.

Hurstwood is a self-made man who manages what Dreiser describes, with characteristic awkwardness, as “a truly swell saloon.” Now a salaried manager, Hurstwood “had risen by perseverance and industry, through long years of service, from the position of barkeeper in a commonplace saloon to his present altitude.”

In his introduction to Hurstwood, Dreiser makes an astonishing error that shows how little the young novelist knows about the highest levels of American society. He describes the saloon manager as “altogether a very acceptable individual of our great American upper class—the first grade below the luxuriously rich.”

The error occurs in part because Dreiser himself is impressed by Hurstwood’s appearance: “For the most part he lounged about, dressed in excellent, tailored suits of imported goods, several rings upon his fingers, a fine blue diamond in his necktie.” Such a man, Dreiser thinks, cannot be far below “the luxuriously rich.” Yet Dreiser shows that Hurstwood is really little more than a maitre d’hôtel: “He had a finely graduated scale of informality and friendship, which improved from the ‘How do you do,’ addressed to the fifteen-dollar-a-week clerks … to the ‘Why, old man, how are you,’ which he addressed to those noted or rich individuals who knew him and were inclined to be friendly.”

Though Dreiser misjudges his status, Hurstwood does have stature—the stature of a competent man who runs, though he does not own, a thriving business. The owners know his value: “His grace, tact, ornate appearance gave the place an air which was most essential. … Bartenders and assistants might come and go, … but so long as he was present, the host of old-time customers would barely notice the change.” Hurstwood has earned the satisfaction of brushing elbows with successful merchants and answering questions about his wife and children that “were made in that perfunctory manner common to Americans of the money-making variety.”

The typical hero of a Horatio Alger novel, the writer John G. Caweiti has pointed out, rises not from rags to riches, but from rags to respectability. This is Hurstwood’s story before Sister Carrie begins. Dreiser shows us the American dream in reverse: from respectability to rags.

Once he begins to fall, Hurstwood cannot stop. He grows in stature as he falls, because he fights against failure with every ounce of his strength. A hard-working, frugal man is supposed to rise in America, and Hurstwood has risen—once. He imagines he can do it again. But his luck has run out, and pluck without luck is nothing. Hurstwood’s long descent is as terrifying as anything in American literature.

One slip dooms Hurstwood, as one stroke of luck lifts the typical Horatio Alger hero. Success and failure, Dreiser suggests, do not depend on character. True, Dreiser shows Hurstwood being punished for his sin, but he also shows Carrie being rewarded for hers. This is not reassuring.

Hurstwood might rise again, but he doesn’t. Life might be different, but it isn’t. God, Dreiser suggests, does play dice with the universe.

What about Carrie? She rises, though not quite to respectability. And her rise does not quiet the ache of yearning within her. This point is made more clearly in the version of Sister Carrie originally published in 1900 than in a manuscript version published in 1998 by the University of Pennsylvania Press. In the version most of us know, Dreiser ends with an apostrophe to Carrie in her rocking chair: “Oh, Carrie, Carrie! Oh, blind strivings of the human heart! … In your rocking-chair, by your window dreaming, shall you long, alone. In your rocking-chair, by your window, shall you dream such happiness as you may never feel.”

After Dreiser’s death in 1945, H. L. Mencken sent his widow a statement that tried to express what Dreiser had meant to American literature. “While Dreiser lived all the literary snobs and popinjays of the country, including your present abject servant, devoted themselves to reminding him of his defects,” Mencken wrote. “He had, to be sure, a number of them. For one thing, he came into the world with an incurable antipathy to the mot juste; for another he had an insatiable appetite for the obviously not true. But the fact remains that he was a great artist, and that no other American of his generation left so wide and handsome a mark upon the national letters. American writing, before and after his time, differed almost as much as biology before and after Darwin.”

I imagine that Dreiser, a monumental egotist, would have liked this tribute, as I imagine he would have liked the movie version of Sister Carrie made by William Wyler in 1952. If you ever have a chance to see Wyler’s film, grab it. You will see Eddie Albert give the performance of his life as Drouet. You will see Jennifer Jones as Carrie. And you will see a Hurstwood you will never forget, played by, of all people, Laurence Olivier! Like Sister Carrie itself, Olivier’s performance as Hurstwood is a treasure that ought to be rediscovered.