I’ll Be Seeing You

The search for traces of a beloved writer led to an uncertain pilgrimage—and a friendship that endured over distance and time

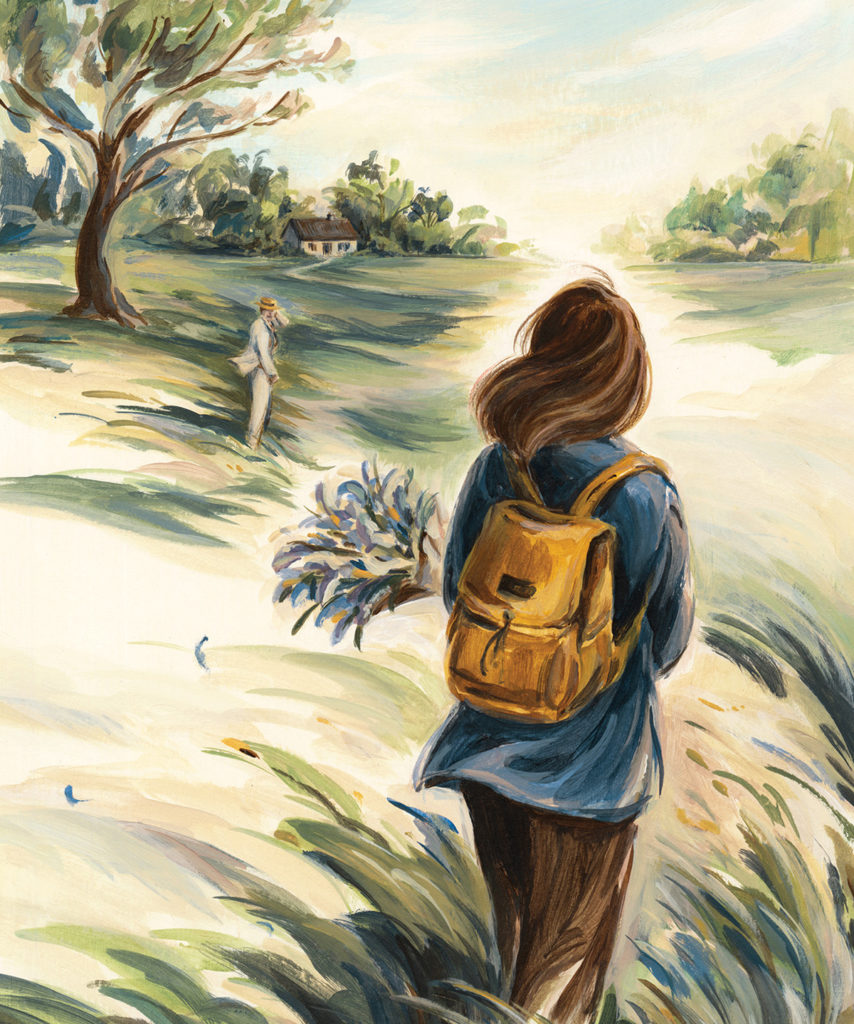

She stands where she was instructed to wait, a bouquet of iris wrapped in butcher paper in one arm, tape recorder bulking up her backpack, as he comes (surely this is the man who had answered her letters) down the overgrown cow path.

Three cows mooching along, heads lowered, as he weaves around them to get past. On his neat, smallish head, a stiff straw boater. Is there a ribbon? Faded black grosgrain, yes.

But her nerves! Butterflies beating within—the two letters between them having been their only link until this moment, and she in no way a professional, never mind the tape recorder. He threads his way past the lethargic cows, she waiting by the sagging wooden bench that serves as the bus stop. He might have stepped out of an Edwardian country weekend novel, in his boater and cream linen suit. Trim dark mustache. Everything about him trim, as his two letters had been precise, briskly instructive.

Did I say this is England? Somewhere in the New Forest. A train from Waterloo, transferring at Salisbury into a lumbering bus to—that place is lost. She had waited, wherever that was, for another conveyance, a kind of jitney (his instructions had been exact—only the one stop Sundays, do not move from the spot, trust it will arrive). She was finally deposited at this place, as his letter had said. But it seems—what with the cows, the overgrown path, the end-of-the-line look of the place—like no place at all.

Yet he has appeared as promised, calling her name in a voice she will come to treasure for its amused fussiness, its covert kindness, a question mark lifting at the end—Patricia? Patricia?

Me, yes.

But there is no remembering so much of this. The fiction writing of the recording mind has stripped away many details (what I wore—dress? slacks?), while time has giantized others (iris, tape recorder).

In any case, the tidy man was only meant to be a bridge figure, his purpose to lead me to the mysterious LM, as I’d learned to call her from the memoir she had written. But even she was not the point of all my effort.

She too was a link, though a precious one, the only living connection to the ghost I stalked. Katherine Mansfield. The romantic renegade writer, older by five years at her death at 34 in January 1923 than I was/am on this June day in 1975.

My first “trip abroad” (a phrase then still common, oddly antique now). The journey from home in St. Paul had been made for this encounter, to interview Mansfield’s best friend, possibly a one-time lover, it was said—would the girl burdened with flowers and tape recorder nerve up to inquire about that ?

LM was the ancient leftover not only of their relationship, but of their world. She, Leslie Moore, had been coaxed into writing a memoir—Katherine Mansfield: The Memories of LM—by the man wearing the stiff boater. And now she had agreed to let “a young American” who had read her book meet its author for an interview.

I had a commission from Ms. magazine (all the feminist rage back then) to do a piece on this friendship. I held pridefully to that commission: this might be my first trip to Europe (to anywhere), but I was no tourist. I was all business.

The interview had been arranged by the man in the linen suit—Peter Day, he said smartly as he approached, the name as tidy as himself. He pivoted immediately and began retracing his steps up the flinty cow path. Come along, he called back to me, come along. That bracing Brit carry-on voice. And I, eager to heel, trooped close behind with my gear.

What a measured, ceremonial dance it was, then, to make connections with strangers before the frantic blur of the Internet, the mosh pit of email and social media. Hi (or even Hey) Patricia! people I have never met chummily greet me online today. Gone, the crisp Dear Miss Hampl of yore, that salutation reading now like an endearment, not a formal address.

My friends in those years were taken up with Virginia Woolf, whose letters and diaries were beginning to appear. But my crush was Mansfield, where the pickings were considerably slimmer. I had my much-marked copy of A Room of One’s Own, but I didn’t quite trust Woolf. She might be a genius, but my Midwestern insecurity was miffed by her snobbery. But then, there is no hauteur stiffer than that of a thin-skinned provincial.

Woolf’s diary report after first meeting Katherine (as I already thought of her, chummy myself all those years ago) ignited this mistrust. She wrote that she (and her husband, Leonard) could only wish that [one’s] first impression of K. M. was not that she stinks like a … civet cat that had taken to street walking. In truth, I’m a little shocked by her commonness at first sight; lines so hard and cheap.

Then, reversing field, she allows, However, when this diminishes, she is so intelligent and inscrutable that she repays friendship. … We discussed Henry James, and K. M. was illuminating I thought.

Too late! Woolf’s reversal seemed to annoy me more than her initial repugnance—a touchiness, no doubt, on behalf of a fellow provincial, a New Zealand colonial–Midwestern flyover sisterhood.

Mansfield wrote her own post-meeting take on Woolf: I do like her tremendously. … I felt then for the first time the strange, trembling, glinting quality of her mind … she seemed to me to be one of those Dostoievsky women whose “innocence” has been hurt.

A keen, almost psychic reading, impersonal, not as judgmental as Woolf’s, and all the more penetrating for that.

After reading LM’s memoir, I devoured a book by a Mansfield scholar (maybe the Mansfield scholar), Sylvia Berkman, who had also written the foreword to LM’s memoir. The bio note below Berkman’s author photo says she taught at Wellesley. But wait, I have the book before me now: there is no author photo. Pixie memory at work again: I seem to have snapped one inwardly because when she comes to mind, there she is—string of pearls, steady hooded gaze. Her book, Katherine Mansfield: A Critical Study, was published in 1951, so a dated book in 1975. But so what? All Mansfield intel was a news flash to me. Her introduction to LM’s memoir was her bona fide. She must actually know LM.

I would give a lot to see the letter I wrote to Sylvia Berkman, sent no doubt to her publisher (Yale University Press). Did I trumpet the Ms. magazine commission? Maybe not. But wait again. Did I actually have a commission from Ms.? I know I had written a letter to the editors asking if they would be interested in a piece about the friendship between Mansfield and LM. Did I get a response? Never mind, I considered myself “on assignment,” even if no one else did.

Most likely, I was canny enough to gauge that an ardent amateur, young enough to be taken for an enterprising student, would fare better at getting an address for LM.

Berkman did not disappoint. In less than a week, in came a blue envelope, unfaded in memory. Within, a single sheet. That is lost, of course. But I was confirmed in my shrewd choice of presenting myself as an acolyte, not a magazine writer on the job. I remember, I think accurately, one part of her brief reply: I will trust you with Leslie’s address. You sound like a nice person.

I suppose I sent a thank-you note.

I wrote to Leslie Moore. And again within a week, a response, though not from LM. This one came on letterhead from Michael Joseph Ltd., London, signed Peter Day, Senior Editor. Miss Moore would see me. I should send my travel dates. June, wasn’t it? He gave me two possible Sundays in June, Sunday being the only possibility. He would be at the bus stop to meet me.

One more exchange between us, me with the Sunday date, him with the precise instructions leading me from Waterloo station to the cow path. It would not have occurred to me—or to him—to exchange telephone numbers. After our transatlantic airmails, trust alone linked us. This Peter Day, Senior Editor, would show up, and I, nice person from St. Paul, Minnesota, would somehow make my way to the assigned spot.

This decorous volley was how it was done in 1975.

First lunch, Peter Day said as I trailed behind him. Then he would wash up, and I would go with Leslie (as he called her) into the sitting room and have my interview. She’s stone deaf, he said. I would have to bellow. And almost completely blind. Oh dear.

Once off the cow path, we walked a long way, through a meadow, a lot of green. Then suddenly, as if conjured, a thatched cottage rose up, a magical toadstool house sprouting in the deep green of wherever we had arrived. A casement window had been thrown open. In its frame an elderly female figure sat in profile. She did not turn, did not move. She gazed ahead into the room, not out the window. A stately head, formal, the nose prominent, as if in a sustained act of sniffing the air. The hair a flattened floss of white. It was a head resigned from beauty, beyond questions of attraction, held fast in selfless dignity.

Impossible to know if she had ever been a beauty—or not. For some reason, I flashed on the portrait of Whistler’s mother. Not because this parchment-skin woman had the same features, but because she bore a similar hieratic calm. It was not just an old face. It was a face in waiting—as if waiting were the real point of life. Waiting for the next thing that was now the final thing.

As we came closer and this profiled figure made no move, a shot of social embarrassment amounting to shame pierced me—I had no business staring at this unguarded being who surely had no idea she was on display in the window, no right to poke around in her memories. Her face held the impersonal calm of a death mask.

The improbable thatched cottage (I’d seen only one in fairy-tale books from childhood) no doubt added to the spooky sensation of intruding on this almost unreal stranger framed in the casement. Still, she did not move. She took no notice of anything, certainly not of our approach. Yet her attention seemed fixed.

Peter Day banged his way into the house, calling out—Leslie, Leslie, here we are! I’ve brought back the American girl. It was the same theatrical voice telling me to Come along, come along as he led the way up the cow path. A commanding voice, but comic, self-satirizing, masking that closeted kindliness I had sensed right away. Did I realize from the start how unfailingly generous he would be, would always be?

The table was already set in the woody room, the room with the open casement window. A square table of dark oak, polished to a dull sheen, linen placemats and crisp napkins that I admired (serviettes, dearie—napkins are what you call diapers, Peter Day briskly correcting, no condescension, just copy editing, part of the job). He pottered around in the kitchen, barking out cheery remarks to Miss Moore, as I decided to call her—somehow I couldn’t call her LM to her face, and to say Leslie was unthinkable.

I have no recollection of being introduced to her. I was relieved of my iris, which reappeared in a stone pitcher, though perhaps never actually seen by LM in her virtual blindness. Gone as well what we said, what we ate, though a soup plate has appeared, and Peter Day is holding a big-bellied ladle. The kitchen, offstage, eventually was the source of coffee and a cake out of a white bakery box. Peter (as by now he had instructed me to call him, waving away my Mr. Day) had brought “the pudding,” he said, from an excellent shop near his flat in London. I was baffled. Pudding? This was cake. Was there to be some kind of custard after the cake? Or with it? Don’t ask.

I was preoccupied with worries about the tape recorder—would it work? Worse, would my elderly prey be put on alert and refuse to divulge any of the delicious “material” I hoped for? Peter shooed me into the adjoining room, smaller, darker, but cozy. I set up the recorder on a low table, and spoke softly into it as to a trusted confidante, played it back—yes, works! Then Peter guided LM into the room. She was taller than I expected, now that she was up, out of her Whistler’s mother pose.

Patricia is going to ask you about Katherine, Leslie. She has come all the way from America to speak to you about Katherine. A brief encouraging nod to me, and back he went to the kitchen to clean up.

Alone at last. But in fact, I desperately wanted Peter to return, his bright voice, his easy command of this giving-nothing statuesque figure. I remembered to bellow: Would it be all right to record our conversation?

Why? It was the first word she spoke to me. Before I could find an answer, Peter boomed from the kitchen, Just answer her questions, Leslie. The mask of a face scowled slightly, settled back.

Where do you live? Asked peevishly. She was interviewing me, apparently.

St. Paul, Minnesota.

No jot of recognition. I was from nowhere.

I expressed my admiration for her memoir.

Peter brought it together, she said, dismissing authorship. I moved on to my love of Katherine Mansfield’s stories, especially the New Zealand ones “At the Bay” and “Prelude.” The Letters and the Journal meant a great deal to me too, I offered.

No response.

It was alarming to be hollering this ardent testimony, as if to a large audience in a great hall.

Then, remembering Ms. magazine, I launched into business, bawling, What did you and Katherine Mansfield think of the early feminist movement?

A brief caesura, then her low growl. We didn’t talk about it. We didn’t think about it.

So much for any possible tweezing out of romantic disclosures. A dread silence fell between us, or maybe had been there all along.

I heard myself asking idiotically, frantically, Well, I mean, what did you talk about?

Her swift, furious reply: The flowers, what was coming up that day. About dinner, what we would have for dinner.

Peter stomped in, a dish towel in his hands. Leslie, stop that right now! Be nice. This girl has come all the way from America to speak to you. A satisfied look on the weathered, chalky face. She had the attention of the one who mattered.

Surely there was more to the interview in the dark room, the two of us seated on either side of the softly whirring cassette recorder on the coffee table, I crouched low, she regal, aloof. For how long? I cannot report. Even the cassette tape disappeared at some point. It’s all gone, except the misery. It was gone even as I sat there, a nice person all the way from Minnesota, a person who didn’t even know what a pudding was.

Peter and I were to take the same train back to London. I was glad of the companionship, even though he’d been witness to my humiliation. The train from Salisbury was crowded. He sat across from me, slumped in his seat, long legs stuck out, the straw boater pulled down: taking a nap. I sat up straight, dry-eyed in my gloom, glad the boater protected me from his gaze.

I was returning to my dirt-cheap Bloomsbury B&B that smelled of kippers, kippers I would be served in the lower-level breakfast room the next morning, along with a slick sausage, two eggs, the whites cruelly fried, as if electrocuted, sizzled brown. Potatoes, gluey in some kind of motor oil. Yet more weirdly, a puddle of rust-colored beans leaking into it all. Cold toast scraped with hard, resistant butter. A mug of tea so black and sludgy, no amount of milk could tame the tannin. My stomach roiled all day.

I had to eat this meal, the Cheerios and skim milk of my native place a world away. The breakfast came with the cost of the room, the second B of the B&B, and I could only afford one other meal a day. I had to tank up every morning, the gassy petroleum belches of the big red buses coming in the lower-level windows open to the street, the reek of exhaust joining the kippers and egginess, creating a tincture more repellent than any civet cat.

The misery of the LM fiasco was morphing, as I sat in the train, into this fret about the upcoming breakfast. Not only did the gorge rise in anticipation of the kippers. Worse, I was afraid of the B&B owner, who stood guard over the crowded tables. This older woman (everyone was older then, just as now, everyone is younger), with her steel hair in a tight bun, expected me not only to clean my plate but to enjoy it. To be grateful, even. She was proud that her house offered a full English breakfast. Not like some with their “continental” breakfasts, mind you.

It was the beginning of my understanding that I was not actually a nice person, but an aggrieved people-pleaser, a concept whose label I had not yet learned. I had no weight in social interactions. Inwardly, I was wringing my hands at every encounter. I could not pry disclosures from LM, too fearful to finesse her crabbiness, not sly enough to charm her into confiding in me. Apparently, I was prepared to be nauseated every day rather than disappoint the breakfast room matron with her cellblock visage.

I glanced up. Peter was looking at me, the straw boater pushed back. He was smiling, an amused smile. What had I revealed of myself, staring off, unguarded in my various miseries? Whatever I had radiated of my unhappiness, he had made a decision.

How would you like to come to a literary dinner at my flat Tuesday evening? Just a few other writers. Come early, I’ll show you around. Shepherd’s Bush.

A few other writers? As in, including you. Yes, please.

I arrived a half hour before the other “literary” guests. God help me, with yet another bunch of iris. Well, my father was a florist. At least no tape recorder.

The flat was crowded with chintz-covered chairs, several of which had been pulled up to a table set for dinner in the living room (sitting room, dearie—the copy-editing voice). On the shelves not only books but also an astonishing array of ceramic pitchers and cachepots, figurines (dogs, horses), and assorted pieces of beflowered china sets. Every Saturday morning early to Portobello Road, Peter said. I’ll take you. So many treasures.

I was told to leave my jacket on the wooden coat tree in the entry. There, perched at a jaunty angle on the knob at the top, was the straw boater. Old friend.

The other guests—just two—were women perhaps 10 years older than me. A curator at a museum on her way to becoming an influential art critic, the other with a second novel coming out in the next season’s list. We settled in with drinks, Peter, aproned and busy about the meal, coming and going. I was asked about my work. Peter called from the kitchen, She has interviewed Leslie, and is working on a piece about Katherine for Ms. magazine. And a book of poems soon, yes?

I was accounted for. I too was literary.

Peter retailed LM’s bad behavior. Suddenly it was all amusing, the other two women hooting. Not a shame, but a story. Leslie was impossible, completely impossible. The way she can be. The two women laughed again and agreed. I laughed along with them, easily disloyal to my heartache. Everyone agreed LM was impossible, knowing her from earlier stories Peter had told. It turned out he went down to the thatched cottage almost every Sunday to be sure LM was all right. A faithful proto-son.

During dinner, the conversation turned to class distinctions, how accents and certain locutions in Britain revealed all and permanently classified each person. I, for instance, am … And Ann is … To this, Ann, the higher-born woman, gave a self-deprecating aristo wave of the hand. More laughter.

The mysterious pudding was revealed as a tangle of upper class–lower class gamesmanship. Pudding was—or had been—the lower-class word, supplanted by the more haute dessert. But when the lower classes began to adopt dessert in an effort to rise, at least linguistically, the toffs (another new word) had cruelly changed the rules, reverting to pudding like the old boys they were. It was all based on public school folkways. (More secret lingo, public school meaning a private school). Pudding, once lowborn, had risen, if its original speakers had not.

It was explained that, as an American, I was out of the running of all this. You could be anything.

Trying to join the game, I offered that I was middle class, maybe lower middle class, Midwestern. No, no—that didn’t compute at all, made no mark. I was an American. Full stop. Sorted. Slotted.

What about me? Peter asked, evidently charmed. Where do I fit?

Oh Peter, but you’re unclassifiable. Your accent is pure homosexual. It completely cuts through all distinctions.

This struck them all as hysterical. Much shrieking. My own smile was wan—I was startled by the frank word. I had understood Peter was “different,” as we said deferentially about some of the floral designers at my father’s shop. They were, like Peter, somehow uniquely gifted. To be respected. But you didn’t say it, certainly not to their face. In fact, not at all. There was, along with the respect for their otherness, a faint aura of disability that it was only polite to ignore. The word gay (or, more provocatively, queer) was not yet heard in St. Paul, and not apparently in London among these literary savants. Peter was delighted, but I felt strangely protective of him—who proved in no need of protection.

I date a slow-dawning liberation from this moment, this glee in teasing a beloved pal who adored the teasing. He, a homosexual, and I, an American, were free of it all. Whatever “it all” was.

Oh class, dearie, he said later, when I stayed to help with the dishes. It’s all about class here. He and I didn’t figure in it, he said, and that was freedom.

There was no profile for Ms. magazine—obviously. In Peter’s sitting room at the literary dinner, my failure with LM was a hoot. But alas, it was only a tale to dine out on. There was no magazine “piece.” The girl with the bunch of iris and the bulky tape recorder brought back only unusable broken bits. And a full measure of embarrassment—I had failed.

Home I went a week later, with a small faience pitcher in milky pink and brown from Portobello Road (Peter nodding approval) that I wrapped carefully in a bright spangly scarf, also found for a song the Saturday we went early to the market. Peter frowned at the scarf, but sighed. There were treasures to be found. He was showing me—history was in objects, if you had a sharp eye. And then there was disposable junk. I was taking home an example of each. I was keen for the bright scarf and thought, but didn’t say, that I would pass along to my mother the fussy little pitcher.

I had scored a wonderfully cheap roundtrip ticket with an ingenious itinerary, from Gatwick to Winnipeg, where I would make a connection home on Northwest Airlines to Minneapolis–St. Paul. I had $1.35 in my jacket pocket as I boarded the plane. No pounds sterling, just this American money. My thin sheaf of traveler’s checks was gone. I was not in possession of a credit card.

No worries, I would be fed on the plane, and then I’d be on the connecting flight home. Clockwork. I don’t recall any anxiety about being virtually penniless and entirely alone half a world away. I wedged myself into my sardine-can middle seat, second-to-last row, surrounded by smokers hazing up the place, scent of the toilet wafting now and again. The way it was.

The London plane was late departing, very late. The connecting flight to Minneapolis, the last flight of the day, had left Winnipeg long before we landed. Everyone else seemed to melt away as we emerged from the plane. I was given a revised ticket for a flight the next morning, and I settled into a plastic seat behind a large pillar in the almost empty Winnipeg airport.

The American dollar was worth more, wasn’t it, than the Canadian? I could get something to eat or at least drink. But no, everything was closed. Everything. No vending machines even, though American money probably didn’t work in them anyway. But was I really hungry? Sort of, but once you fall asleep, you forget that, right?

An hour or so later, an older man in a uniform lumbered up to me. I had to leave the building, he said, not unkindly. The building was closing. Actually, it was already closed, he said, but he had just discovered me behind my pillar. He pointed to a van idling beyond the large window, the free transfer to a nearby hotel. Take that.

The hotel struck me as a comfortable place, not impersonal and motel-cold, gray carpeting with a twirling rose floral pattern. An old-fashioned reception desk curved around a whole corner of the lobby. A man about my father’s age stood behind it, attending to some papers, his glasses down his nose. He had the look of a seasoned high school teacher grading exams. He regarded me above the glasses as I passed by, a neutral look (good), and returned to his papers.

The hotel diner, behind glass swing doors, was open, though the only person inside was a middle-aged waitress behind the Formica counter, smoking a cigarette. I saw from the menu taped to the window that there was nothing I could afford except coffee. But who wanted coffee in the dark night of the soul?

I made my way to an upholstered banquette set around a large pillar. The safety of pillars. It was unfortunately within view of the man behind the reception counter. I determined not to look at him because not looking at him made me invisible.

But the eye has a mind of its own. I looked up. And there he was, the glasses still lowered, his gaze fixed on me. Then the hand up, finger curled, motioning me to come forward.

Where was I staying for the night?

I explained about the plane, and that if it was all right—the people-pleasing ingratiation rolling off me—I thought I would just sit in the lobby. It occurred to me then that I had no plan for getting back to the airport. I didn’t mention this, intent only on securing my place for the night on the banquette by the pillar.

He didn’t seem to be looking at me anymore or attending to how I answered. That was a little concerning. I tried to be winning, radiating harmlessness and rectitude. But he was having none of it, busy writing something on a small piece of paper. Then something else. He reached under the counter—could he have pushed a button to alert security? I was a vagrant, after all. Well, maybe the police would take me back to the airport. Also, I’d heard of backpackers being allowed to sleep in jail cells overnight. That would be an experience.

Have you had dinner?—the dark eyes now up and on my face, the frameless glasses little guard windows. Before I could answer, he was handing me the small paper—a ticket for the diner—and then another, this one for the airport van. (If anyone asks you in the morning, just say you’re a stewardess, though surely we both knew I was an unlikely flight attendant, streaming hippie hair, worn bell bottoms.) Then a key for a room on the third floor. Get some sleep. Be sure to lock the door. I would get a wake-up call early in the morning.

It was only as my mass of troubles disappeared in his kindness that I felt how frightened I’d been. I began to blubber a bit. What was the cost of the room and the meals? What was his name and the address here? I would send him a check, promise. I may even have held up my hand, Scout’s honor. Yes, I did that.

The eyes closed for a tired moment, the soft pallor of his indoor face, the sagging gray suit and the maroon tie. That won’t be necessary.

Sometime in the future, he said, dark expressionless eyes back on me, I might be in a position to help someone myself. He pointed to the diner, which was closing soon. The chit he had given me, he said, was good for something in the morning, as well.

At the diner door I turned, intending to smile, give him a friendly wave to show how grateful I was. But the glasses were down the nose, eyes turned again to his papers where, I had seen, there were no words, only rows of numbers.

Peter liked to say, as our correspondence over the years moved from typed letters on letterhead to cards and handwritten notes, and finally to the astonishing immediacy of email, that the only thing worse than someone who failed to answer a letter was a person (himself) who answered instantly, thus sending the shuttlecock of communication back into the other person’s court.

I gave as good as I got: we wrote and wrote to each other, serving and returning serve across the transatlantic net. Occasionally I visited London, and once—amazingly—he visited St. Paul after I married. I had the impression he was checking out this husband who seemed to pass muster, who knew a great deal about the poetry of John Donne and had the right sense of humor and an ability to be irreverent— even as they both had a strong Anglican gene, which I did not share, both of them loving the language of the Book of Common Prayer.

At some point, Peter became heavily involved with the English PEN Centre and took an active role in International PEN, which put him in touch with writers across the globe. Like all naturally generous people, he was a fabulous gossip. He gassed on about “names,” allowing himself to be outraged in particular by Susan Sontag, who in the late 1980s was essentially his PEN America counterpart—total phony, terrible person. I was all ears.

Peter continued to aid and abet my efforts. When I had a commission (a real one) to write a piece about Venice in winter, he put me in touch with a Dallas heiress he knew from her donations to PEN. She has a place on the Grand Canal—you can describe it. He had written to her, asking (requiring) her to befriend me. I got my invitation to the palatial residence and was given a detail useful for my travel piece: from her balcony overlooking the Canal, she watched to see when the people standing in the gondolas were outnumbered by those sitting: that meant more tourists than locals—time to go back to the ranch.

Peter reported, without much ado, that LM died in 1978. She made it to 90.

A new Mansfield biography by Claire Tomalin appeared in 1988, subtitled A Secret Life. It was the third major biography of this “minor” writer with her slim shelf of books, dead at 34, handicapped by illness since her early wild-thing 20s. She was seriously ill her entire writing career.

Tomalin’s biography was a revelation, outing Mansfield as a kind of sexual liberation martyr and clearing the mists about her illnesses—not simply tuberculosis (which did indeed kill her), but also gonorrhea, which she contracted after a pileup of what my mother would have called “bad choices.”

She had become pregnant soon after her arrival in London from Wellington, then madly married another man she knew casually to cover this indiscretion, and bolted from him within hours of the wedding, never apparently consummating the union, but now “a married woman”—and pregnant.

Her father was a prominent Wellington man—chairman of the Bank of New Zealand and eventually knighted. In a photograph in Tomalin’s biography, the mother is striking, even imperial, a wide velvet choker around her elegant neck, aloof face offering mild disdain. The look conveyed not snobbery but implacability.

Hearing from her London relatives the state of affairs, this eminence came steaming over from New Zealand and took the unruly daughter off to a spa in Germany. Having deposited her daughter in the care of others, the mother sailed back to Wellington, where she cut the daughter out of her will upon arrival. Katherine was alone when she miscarried the baby that had occasioned both her marriage and her mother’s alarm.

Katherine stayed in Germany alone, recovering, writing the stories that would form her first book, In a German Pension, published in 1911. She also got herself into the brief, infected liaison that led from gonorrhea to tuberculosis to her death.

Tomalin’s reconstruction of it all includes the misbegotten surgery that followed the discovery of her infection but that did not cure her, instead releasing the bacteria into her system, rendering her not only sterile but subject to increasing pain, which she took to calling her “rheumatiz.”

The shame was profound, bound up in a virtual omertà she kept about her condition. Nor did she really comprehend what had happened to her or how catastrophic it was.

In 1991, Tomalin returned to Mansfield as a subject, writing a play, The Winter Wife, that was produced in London. It was about the relationship between Mansfield and LM, a friendship that began in girlhood at their London boarding school and endured until Mansfield’s death in France, surely becoming more essential to Mansfield as she became a virtual invalid, needing care.

There was no lesbian love between them, as I had hoped to ferret out when I visited the New Forest cottage, but love there was. And dependence. The love was unconditional—LM’s. The dependence, sometimes the infuriated helplessness of an invalid, was Mansfield’s.

They shared a mystical belief in friendship that they both felt was as sacred as marriage. And given Mansfield’s disappointing marriage to the literary critic John Middleton Murry, who was only relieved to have someone else take over for him as caregiver, their friendship was profound for both of them, if more soulful on LM’s side.

Peter went to the play’s opening. An early scene, he reported, had the two women on a train headed to the south of France. LM spoke to the porter in comically cracked French as she tried to arrange things, ineptly, for the ailing Katherine. The audience, loving the slapstick, erupted in laughter. Peter was enraged—Leslie’s French was perfect, he wrote me. She spoke the language far better than Mansfield. How he knew this wasn’t clear.

He rose from his seat and called out as if he too were onstage, This is a lie, a complete lie! And stomped out of the theater, clambering over the people in his row, nicely disrupting opening night. He seemed, in the telling, quite pleased with his own performance.

I relayed this episode to a close English friend, a writer fierce about accuracy, committed to truth telling. I thought she would relish the tale. She was appalled. That just isn’t done.

Deep rooted in my loyalty, I only wished I’d been there to stalk out with Peter.

Things began to fall apart. Or Peter did. He’d been a brilliant editor, a reader with a pitch-perfect ear, able to pluck a gem from the flotsam and jetsam of the slush piles he went through at warp speed. With this spectacular talent, he was advanced from editor to publisher at a new firm. But being a great reader does not automatically make a winning publisher. Peter’s idea of the bottom line was a great final chapter.

He lost that job, perhaps without regret. Then came a series of “little” strokes. Money became something of a problem for a man who never paid attention to money. Even his “treasures” from Portobello Road were of the teacup variety, and that nice tweed jacket is from Oxfam, thank you very much.

A group of his (many) admirers got him on the list to be housed at Charterhouse, a distinctly English establishment, a kind of grand almshouse for aged single men (called the Brothers) who had performed service, often cultural, to the nation and were in need of housing, though still able to care for themselves. Peter became one of them, moving himself and his books and some of the Portobello treasures into a snug apartment, taking his meals in a grand hall with his fellow Brothers, swanning around the property in the dual spirit of baron and manorial retainer.

He invited my husband and me to visit. Tart instructions: we could stay two nights, no longer. Guests room in a separate wing. Meals with him. Tour of the grounds, the chapel, the works. He was in his element, manuscripts piled by his easy chair (he had become a reader for Little, Brown), chipper with the Brothers as we dined with them or passed them on the lovely grounds, an opera singer, a landscape gardener, a dancer—all “former” versions, as Peter was a former publisher. He had signed on to offer tours of the ancient site, dating from 1348, when it was used as a burial ground during the Black Plague. It served as a Carthusian monastery until the dissolution of the monasteries, when it became a house for wealthy noblemen. The first Elizabeth met the Privy Council there before her coronation.

Peter loved rolling out the history, occasionally embellishing it (in time this tendency relieved him of his tour guiding). He especially loved arriving at 1611 (Shakespeare still alive, the year of the first performance of The Tempest, Peter’s favorite), when Thomas Sutton bought the Charterhouse. Sutton established a foundation to provide a home for up to 80 Brothers, “either decrepit or old captaynes either at sea or at land, maimed or disabled soldiers, merchants fallen on hard times, those ruined by shipwreck or other calamity.” Peter’s people, though no dancers or opera singers in that early roll call.

In addition to all his friends from his publishing days, he claimed as family a young British diplomat I never met, a married man with small children, his virtual son who watched over all the practicalities of life for him. Peter was always on the prowl for comic gifts for the children. The diplomat was posted to Sri Lanka. To my surprise, about a year after our visit to the Charterhouse, I received a postcard from Colombo: Peter was spending several months there with the family—his family, as he put it.

Then, suddenly it seemed, the emails between us dwindled, became rare. Peter wrote that he could no longer manage the computer or even the typewriter. Apparently there were more “little brain episodes.” My husband was ill as well, heart and lungs. It seems impossible, but the trail we had trod all the years since 1975 in the New Forest went cold. Yes, I blame myself. But what is such guilt but self-promotion?

A year or so after my husband’s death, I suddenly thought—Peter! And was determined to get back in touch. But something—reality, no doubt—sent me first to Google. And there he was in the remembrances of those who, like me, had been beneficiaries of an insight that always led to kindness. And to loyalty, prudent or not—his naughty cri de coeur at the play whose opening night he managed to mar.

I didn’t even have anyone to write to, no condolence note to the adopted son diplomat whose name I didn’t know. My connection now, shockingly, seemed fragile, hardly worthy of grief. I was, after all, one of a number, at the end of a long line. I had lost the connection. Peter didn’t lose it—he had been too impaired at the end to keep it. I was the one who allowed the shuttlecock we had kept lofting across the distance of time and space to drop.

I wanted to tell someone how it had been all those years ago, not out of sentiment, not even out of loyalty, but as testament to the astonishment that age brings to the past—I was that person? I was? The past was coming back not as memory but as impossibility.

What I most wanted to revisit—to relive—was that night, after the “literary dinner,” when Peter told me that he and I, outside the confines of class, were free. We stood in the little foyer after finishing the dishes to say farewell. And I did feel free somehow, free to keep going on my hardly begun life, the “literary” life I was trying to snag in my grasping hands, no matter my failure in the thatched cottage.

I took my jacket off the peg of the wooden clothes tree. And there, still perched on top, was the straw boater.

I love that hat, I told Peter. What I meant was that I loved this life I was embarking on, this life he assured me I was free to pursue. And I loved him, him as he had first appeared, jigging down the cow path in the cream linen suit, the boater atop his small, neat head.

Try it on, he said.

But unlike his, my head was not small, not neat. The boater sat atop my mass of springy hair like one of those old-fashioned nurse’s caps, a kind of upside-down cupcake mold. Ridiculous. We were both laughing, looking at my absurdly hatted head in the wall mirror.

Ah, too bad, Peter said, suddenly sorry. His face, usually so animated, ready to be amused, was still, almost grave.

Too bad, he repeated. If it had fitted, I was going to give it to you. It was Katherine’s hat.