Net Gains

Nabokov's profitable summer chasing butterflies and settling scores in the Utah mountains

Robert Roper’s Nabokov in America: On the Road to Lolita, from which this article was adapted, was published in June.

The slender Russian man is on vacation. He has an arrogantly beautiful face and is accompanied by an oddly tall little boy, as he stalks up and down a trout stream in the Wasatch Range, a few miles east of Sandy, Utah. They deploy butterfly nets. “I walk from 12 to 18 miles a day,” he writes in a letter mailed in July of 1943, “wearing only shorts and tennis shoes … always a cold wind blowing in this particular cañon.”

The eccentric Russian novelist chasing butterflies—the signature image of Vladimir Nabokov in America—came to beguile millions. “A man without pants and shirt” was how a local teenager, John Downey, saw him when encountering Nabokov on the Little Cottonwood Canyon road. He was “dang near nude,” Downey recalled, and when he asked Nabokov what he was up to, the stranger would not explain at first.

Nabokov was 44. That November he would have his two front teeth removed, all the rest soon following. (“My tongue is like someone who comes home and finds all his furniture gone.”) He smoked five packs of cigarettes a day and had a tubercular look. For the previous 20 years he had lived on an edge—he was an artist, after all, and deprivation went with the territory. His wife worked odd jobs to support them, and neither of them had ever been much for cooking or packing on the pounds.

To be in America that summer was most excellent luck. The Nabokovs had been through the historical wringer; they were Zelig-like figures of 20th-century catastrophe, dispossessed of their native Russia by the Bolsheviks, hair’s-breadth escapees of the Nazis, “little” people with murderous evil breathing down their necks. Had they been in Russia, they might have been starving to death or dying of cholera during the Siege of Leningrad, the most calamitous siege in world history; had they remained in France, Véra Nabokov, who was Jewish, and her young son, Dmitri, would likely have been on their way to Drancy, the French internment camp that directly fed Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Instead, Alta, Utah. Marmots and Mormons. Here Jay Laughlin, the 28-year-old head of New Directions publishing company, owned a rudimentary ski lodge in a tumbling canyon full of aspens and rock faces. Nearby peaks reached over 11,000 feet. Utah had been only lightly harvested by lepidopterists at that time; its violently up-and-down terrain excited Nabokov, who knew that mountain ranges promoted allopatric speciation, whereby populations of butterflies become isolated and diverge genetically.

[adblock-left-01]

The family, which had been in the United States since 1940, traveled west by train from Cambridge, Massachusetts. Nabokov had written a book for Laughlin, the literary study Nikolai Gogol, and the effort had exhausted him. It “has cost me more trouble than any other I have composed,” he told the publisher dramatically before showing him the manuscript, and “I never would have accepted your suggestion to do it had I known how many gallons of brain-blood it would absorb. … I am very weak, smiling a weak smile, as I lie in my private maternity ward, and expect roses.”

Laughlin was not charmed. He had wanted a simple introduction bringing Gogol to the attention of American readers, but Nabokov did not see himself as a writer of simple introductions. His hilarious, exhaustingly insightful study is more an eccentric gloss in the manner of William Carlos Williams’s In the American Grain (1925) or D. H. Lawrence’s Studies in Classic American Literature (1923), neither of which Nabokov ever admitted reading. Lawrence’s study, in particular, predicts Nabokov’s, with its take-by-the-scruff-of-the-neck approach to esteemed writers and its concern with the irreducible timbre of a writer’s voice.

The publisher’s displeasure with the manuscript cast a pall over the summer. In Laughlin, the “landlord and the poet are fiercely competing,” Nabokov wrote Edmund Wilson (who had introduced the writer to the publisher), “with the first winning by a neck.” Like other scions of great fortunes (Pittsburgh steel in his case), Laughlin was eager not to be taken for a mark, and he drove hard bargains with his writers. He wanted plot summaries of all of Gogol’s books, among other additions that Nabokov found laughable. Nabokov responded with an annotated chronology and a new final chapter, “Commentaries,” that holds the publisher up to ridicule. Laughlin had the good form to publish it as written.

The tone of this new chapter—recalling a well-known sketch by Hemingway, “One Reader Writes”—reports the publisher saying such inane things as, “Well … I like it—but I do think the student ought … to be told more about Gogol’s books. … He would want to know what those books are about.” Nabokov replies that he has been saying what they are about, to which Laughlin replies, “No … I have gone through it carefully and so has my wife, and we have not found the plots. … The student ought to be able to find his way, otherwise he would be puzzled and would not bother to read any further.”

In the Hemingway sketch, from Winner Take Nothing (1933), a woman whose husband has contracted syphilis writes to an advice columnist asking for rudimentary information, including information on whether the couple can ever have sex again. Her ignorance invites ridicule and seems intended as an indictment of American women, or possibly just American wives. Nabokov’s sketch is almost entirely dialogue; usually he disdained dialogue-based writing, Hemingway’s most definitely included in the derogation. But here he uses naturalistic speech to clever effect, showing the thickness of the character he identifies only as “my publisher” with every word out of his mouth. The “I” of the piece is by contrast patient, sane, and wholly justified in feeling exasperated; he is the captive of someone enamored of his own ideas who unfortunately also signs the checks.

A technique often said to be an invention of Hemingway’s—leaving out story elements for a reader to infer on his own—has a demonstration, perhaps parodic in intent, when, after asking for a recitation of the plot events of The Inspector General and having been given a laughably literal summary, the publisher adds, “Yes, of course you may use it,” in reply to an unvoiced request to include it in a revised manuscript.

Nabokov had a ferocious disregard for Hemingway. He also disdained Lawrence and other Anglophone writers from whom he learned and borrowed, such as Faulkner, whom he dismissed with lengthy screeds spluttering with appalled rage. Hemingway was special, though, bestriding the era as an unequaled commercial colossus. In 1940, Hemingway was dominatingly present, with the publication in October of For Whom the Bell Tolls, his long, sporadically excellent, crowd-pleasing novel of the Spanish Civil War. Nabokov admitted in later years to having read some Hemingway (he never admitted to reading Lawrence). In an interview Nabokov granted in the ’60s he said, “As to Hemingway, I read him for the first time in the early forties, something about bells, balls, and bulls, and loathed it. Later I read his admirable ‘The Killers’ and the wonderful fish story.” “Bells, balls, and bulls” conflates For Whom the Bell Tolls with The Sun Also Rises, and “the wonderful fish story” is no doubt The Old Man and the Sea, another crowd-pleaser but definitely minor Hemingway. “The Killers,” all dialogue, was virtually a screenplay—for Nabokov a mark of triviality.

[adblock-right-01]

His attention to the literary goings-on of his period, his hyper-alertness to competing authors, is what can be expected of an ambitious newcomer aiming for prominence. In one of his letters from Utah, he gives a sense of wide, continuous reading among Americans. To Wilson he wrote on July 15 that he had “liked very much Mary [McCarthy]’s criticism of Wilder’s play in the Partisan.” (The play was The Skin of Our Teeth, and McCarthy’s savage notice in Partisan Review called it an “anachronistic joke, a joke both provincial and self-assertive.”) He had also read, and lustily hated, Max Eastman’s long narrative poem Lot’s Wife, just out as a book. Wilson had mentioned the writer V. S. Yanovsky, and Nabokov, displaying no kindness toward a fellow émigré, denounced him as “a he-man … if you know what I mean.” And furthermore, “He cannot write.”

Returning to Western subjects, he said,

Twenty years ago this place was a Roaring Gulch with golddiggers plugging each other in saloons, but now the Lodge stands in absolute solitude. I happened to read the other day a remarkably silly but rather charming book about a dentist who murdered his wife—written in the nineties and uncannily like a translation from Maupassant in style. It all ends in the Mohave Desert.

That was probably McTeague, by Frank Norris.

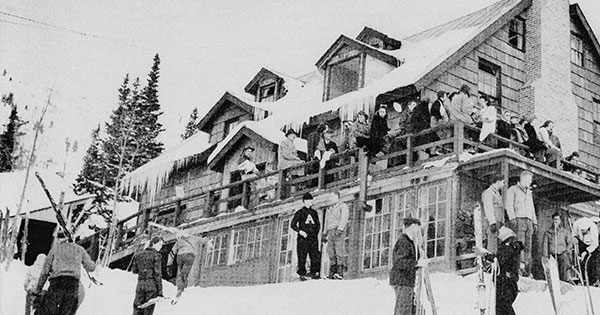

Some of the day-to-day at Alta can be imagined from passages in the Gogol book and also from Laughlin’s accounts of the Nabokovs as cranky guests at his ski lodge. The solitude in the canyon came with touches of desolation; the local silver mines having recently shut down, Nabokov could see “ancient mine dumps” and derelict mine equipment through the plate-glass windows of the lodge. Built four years before by a railroad company, with Laughlin coming on later as an investor, the lodge was a modest wooden structure on a steep slope of Little Cottonwood Canyon, with a snow-shedding roof and a plank veranda built on piers. Inside, stone fireplaces and guest rooms catered to skiers in winter. “A delicate sunset was framed in a golden gap between gaunt mountains,” Nabokov wrote about a view out one of the windows. “The remote rims of the gap were eyelashed with firs and … deep in the gap itself, one could distinguish the silhouettes of other, lesser and quite ethereal, mountains.”

He went out on the veranda nights. He “affixed big lights [inside] the plate glass windows,” Laughlin recorded, “and collected moths half the night.” (Some of these moths he sent to James H. McDunnough of the American Museum of Natural History, who named one species Eupithecia nabokovi in his honor.) Laughlin was astounded by Nabokov’s energy. He “wrote every day and hunted butterflies every good day,” Laughlin told Time magazine some years later. “I never knew what he was writing; he was secretive about that, but I could hear the typewriter going.” (The typewriter would have been operated by Véra; Vladimir wrote with a pen and disdained making fair copies.)

The Russians played Chinese checkers when the weather kept them indoors. Laughlin and his young wife, Margaret Keyser, had a pair of cocker spaniel puppies, and these were often underfoot—“a draggle-eared black one with an appealing slant in the bluish whites of his eyes,” Nabokov wrote, and “a little white bitch with a pink-dappled face and belly.” They were supposed to stay outside but sometimes sneaked indoors.

Despite the rain, “Never in my life … have I had such good collecting as here,” he reported to Wilson. Little Cottonwood Canyon is a wildflower paradise, if sometimes windy. Feeling strong and inspired, possibly, by a resentful or competitive urge, Nabokov one day challenged Laughlin, a champion skier and tireless hiker, to climb to the summit of a nearby peak, a serious ascent gaining more than 6,000 feet in the space of six miles. Modern-day wilderness hikers consider Lone Peak the most arduous high peak ascent in the Wasatch. Two routes to the summit were known in the ’40s; both offered no water beyond the trailhead, and well-prepared climbers carried multiple canteens. There is reason to think the two were not well prepared. Nabokov wore “white shorts and sneakers,” Laughlin told the Time correspondent, and it was “a very tough mountain and the round trip took … nine exhausting hours.” The climb requires careful movement over steep granite, with great exposure—the possibility of a fatal fall—along the towering summit headwall.

The top was all snow, due to heavy precipitation that year. In his Time interview Laughlin recalled that Nabokov on the way down “lost his footing and slid 500 to 600 feet” and suffered bad friction burns on his buttocks. Slides on summit snowfields are often fatal or crippling. Speaking to a different interviewer 20 years later, and recalling events a bit differently, Laughlin emphasized that the outing had had a scientific purpose—Nabokov had brought his butterfly net, and he collected near the snowy summit. Then on the way down,

we lost our footing and began to slide. We were sliding faster and faster … toward a terrible bunch of rocks. [Nabokov] managed to hook his butterfly net onto a piece of rock that was sticking through the snow. I grabbed his foot and held onto him.

The climbers were several hours late returning from their adventure. Véra phoned the county sheriff, who sent out a squad car, and the deputies found the men just as they were getting out of the woods. They then drove them back to the lodge.

Summer over, the Nabokovs returned east by train. Vladimir resumed his work at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology, sorting Lepidoptera, and at Wellesley, where he taught a Russian language class. Relations with Laughlin never quite recovered. In his letters to the publisher, Nabokov often took an imperious tone: a year after the Alta summer, he wrote,

I want you to do something for me. I noticed with dismay that I have somehow mislaid samples of plants which I brought from Utah. … There are several species of lupine around Alta. I need the one growing in the haunts of annetta [a type of butterfly]. … As annetta lives in symbiosis with ants I would also like to have a few [ant] specimens. … Both lupine and ant must come from that precise spot. Kill the ants with alcohol or carbona … and put them into a small box with cotton wool. The plants can be mailed in a carton … but try to keep them flat.

Five years later, writing about a possible reprint of Laughter in the Dark:

Quite independently of whether or not the deal is … profitable … it is essential for me to keep my records straight, and this I cannot do unless I know the exact text of your contract with the New American Library. It is very important for me, so please give it your attention. … I am at a loss to understand why you have not done it before.

Laughlin had sent a copy of The Sheltering Sky, by Paul Bowles, another New Directions author, and Nabokov declared it “an utterly ridiculous performance, devoid of talent. You ought to have had the manuscript checked by a cultured Arab. Thanks all the same for sending me those books. I hope you don’t mind this frank expression of my opinion.”

Something in his tone suggests the patronizing older brother with his nose out of joint—perhaps the memory of the slide on his rear still smarted. Laughlin, in the end, published four of Nabokov’s first books in America, ably introducing him to discerning readers in the company of Ezra Pound, Wallace Stevens, Williams, Jorge Luis Borges, Pablo Neruda, Franz Kafka, Bowles, and other notables. Soon larger publishing houses began offering him larger advances, and Nabokov moved on.