Those of you who have been following this blog know that my wife and I have been in China this summer, a combination of work and pleasure. Most of the time we were in Shanghai, but we also took a day trip to Suzhou, famous for its elaborate gardens. There we toured the Lion Grove, with its stones twisted into grotesque baroque shapes, and the Humble Administrator’s Garden, which, despite its title, is very grand and beautiful. Part of what makes it so is the progression from indoor pavilions (with poetic names like The Listening to the Sound of the Rain Pavilion) to picturesque ponds and waterfalls, the contraction and expansion of the landscape. It is Nature Orchestrated, able to accommodate crowds without any compromise to its picturesque beauty, much the way Central Park or Prospect Park does; and I wondered if Frederick Law Olmsted had drawn on it for inspiration.

In Suzhou, we went to a restaurant on the canal where I ate one of the best meals in my life. Though we have consistently dined well in China, I’ve had three meals where the food was prepared so exquisitely, so subtly, so delicately, that I ascended to an empyrean realm: it was enough to convert me to a foodie, a preoccupation I have always resisted. If I were merely to list the dishes, it would not tell you much, since they were largely the same dishes we encountered in other banquets. Would that I had the skill to put into words the difference between how those three meals tasted and the other perfectly adequate ones we experienced in China.

We are now in Nanjing, where the poet Huang Fan, the man who invited me to China, lives and teaches. Huang is a fiercely gifted poet (or so it would appear from the English translations of his work) and an omnivorous reader, who also teaches Chinese visual arts. He dresses in a uniform that rarely varies: khaki T-shirt, jeans and military cap, an ironic tribute to his youthful ambivalence toward the Army. The first night we were here, I gave a reading of my work, and was heartened to see the overflow crowd of students and local writers (no doubt due as much to Huang’s efforts as to my renown in these parts). The question-and-answer session that followed the reading was so enthusiastic and wide-ranging that I had the sense of an enormous appetite for the consolation of the humanities, for writing in general and perhaps for American thinking in particular. When it finally ended, with many more hands still raised, members of the audience swarmed the front with requests to be photographed with me. Selfies are a big thing in China, and for one evening I was allowed to feel like a visiting rock star.

In the sightseeing days that have followed (with Huang’s wife at the wheel, since he doesn’t drive), I’ve been struck with what a gracious, leafy, and lovely city Nanjing is, especially in comparison to Shanghai. Of course it’s much smaller than Shanghai, only (only!) eight million inhabitants, roughly the population of New York City. Much of the original low-scale environment has been permitted to stand, as well as the shade trees that line many of the streets and form a canopy over them. Some of these old trees have been pruned and trained to stand upright, at parade attention, as it were. There are forests in the middle of the city, and the countryside never feels far away. True, the very same dreary concrete housing estates and megamalls that dominate Shanghai can be found here, but mainly set on the outskirts.

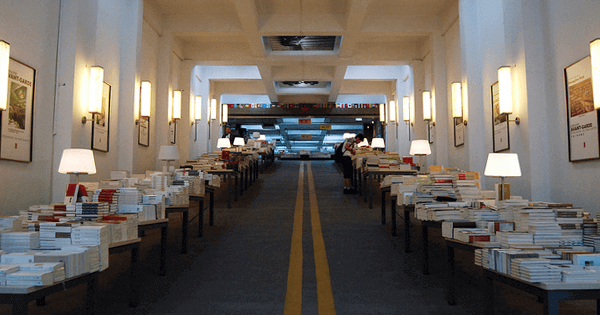

Huang took me to an extremely impressive bookstore, Librairie Avant-Garde, which occupied what had once been an underground garage. The floor tilted upward in the middle and a car was impishly parked inside, to pay homage to its former life. On the walls were posters of international literary heroes such as Beckett, Borges, Pasolini, Sontag, Benjamin. Table after table was covered with rigorously highbrow titles, including lots of contemporary American authors such as Paul Auster, Cormac McCarthy, and Lydia Davis, and French theorists such as Bourdieu, Foucault, and Barthes, as well as the world’s classics and ancient Greek, Roman, and Chinese texts. The film selection carried books on every conceivable cutting-edge director. Throughout the store mostly young people were reading or typing on their laptops, so that it looked like a combination library, study hall, and bookstore. I was floored by the air of intellectual seriousness, as well as the absence of tchotchkes and other merchandise that our chain bookstores sell. It seemed that China was much less closed-off to the world than I’d imagined. Perhaps only books that directly criticize the Communist Party or the present regime are censored, though that makes for a significant gap.

I saw the other side of the coin when at one point Huang’s wife had to return to her office (she works in a publishing firm) to practice a group sing of the new Chinese Communist Party. She refused to sing it in the car for us, having already done it 10 times that day, but played it on her cell phone. I then held forth with a lusty if truncated version of “The East Is Red.” Huang and his wife were astonished that I knew it. We explained that our generation, which was so fervently against the U.S. government during the Vietnam war, had idealized Mao, the Little Red Book, “the wind from the East,” and so on. That was before we learned about the costly errors that resulted. “And now what do you think of Mao?” Huang asked.

“I think he’s one of the three worst killers in history,” and I ticked them off: “Stalin, Mao, Hitler.” The car got rather silent.

“What do you think of your country now?” Huang responded quietly.

“I feel much warmer toward my country, though I know it’s made plenty of mistakes and isn’t perfect.”

In 1990, the first time I visited China (shortly after the Tiananmen Square massacre), it was impossible to detect any enthusiasm for the Communist Party among the film crowd I spoke to; and I sensed on this trip that many Chinese intellectuals and artists continue to live in a kind of internal exile, cautiously silent in public and thinking heretical thoughts in private. For me, the trip has been marked by paradox. I’ve been feeling a tremor of fear that never quite leaves, while passing through a country whose authoritarian regime censors the Internet and throws dissidents in jail if they cross a certain unpredictable line, and at the same time feeling waves of affection and trust toward the Chinese people themselves: their endurance, their culture, their humanity.