On this date in 1910, a most remarkable performance took place inside the opulent confines of the Vienna State Opera house. The program featured a ballet-pantomime called Der Schneemann (The Snowman), composed two years before by an 11-year-old boy, Erich Wolfgang Korngold. The work was a hit, a spectacular success, and Korngold’s career was subsequently launched. Members of Vienna’s cultural elite, even many prominent musicians, began whispering of a Mozart in their midst.

Born in the city of Brünn (now Brno in the Czech Republic), Korngold had the fortune—or misfortune, depending on one’s perspective—of inheriting a famous last name. His father, Julius, was Vienna’s preeminent music critic, whose uncompromising approach made many an enemy, though he also had access to luminaries such as Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss, and upon recognizing Erich’s talent—the boy could play the piano by five and write music by seven—he began seeking their advice. At 10, Erich composed a cantata and played it for Mahler, who pronounced the boy a genius and suggested that he become a private student of the noted composer Alexander Zemlinsky (which he did). No less impressed was Strauss, who advised Julius Korngold to resist the urge to enroll Erich in a conservatory: the boy could learn nothing in school that he did not already know.

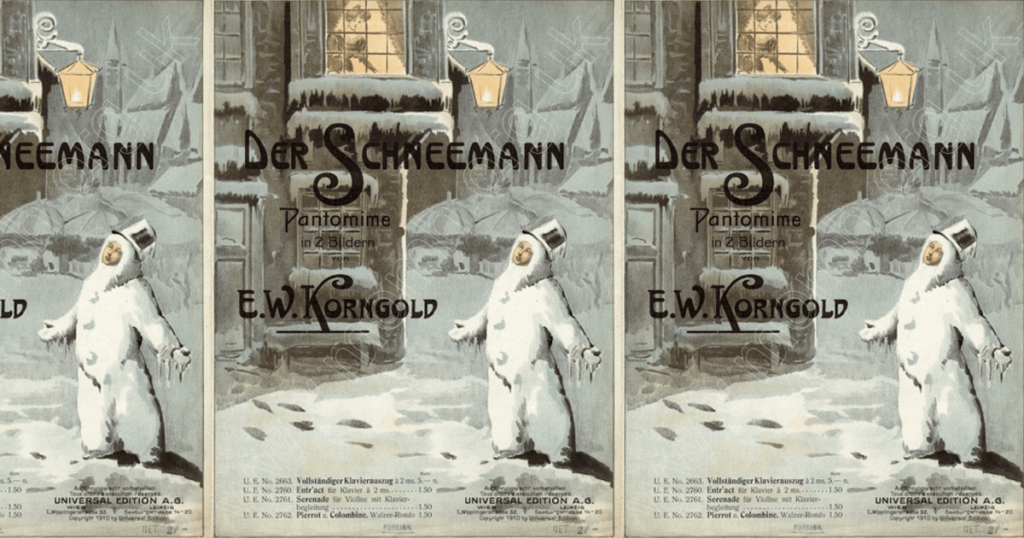

Der Schneemann began life as a piano piece, Erich using a well-known commedia dell’arte scenario (with its stock characters Pierrot, Columbine, and Pantalon) written by his father. Here, Pierrot is an impoverished violinist in love with the beautiful Columbine, whom he gazes upon from his position on his town’s market square. From her window, Columbine looks down lovingly at her admirer, but she can do nothing, imprisoned as she is by her jealous uncle Pantalon, who thwarts Pierrot’s attempts to gain access to the house. Eventually, the fiddler succeeds by disguising himself as a snowman. An inebriated Pantalon passes out and, upon waking, discovers in a rage that Pierrot and Columbine have escaped in each other’s arms.

Korngold scored the work for piano four-hands with violin obbligato, and the initial performances in April 1910—with dancers from Vienna’s Imperial Ballet—were so successful that the orchestral concert of October 4 was scheduled. Korngold was still too green to orchestrate the piece, so this task fell to his teacher, Zemlinksy. Felix Weingarter, who had replaced Mahler as director of the Vienna State Opera, conducted.

Der Schneemann went on to receive many more performances across Europe. Encouraged, Korngold continued to write, composing a piano sonata that Artur Schnabel played extensively and responding to his many commissions with pieces of chamber music and songs. Two one-act operas, Violanta and Der Ring des Polykrates, were premiered by Bruno Walter and were forerunners to his greatest operatic work, Die Tote Stadt (The Dead City). With his theater career now flourishing, Korngold became a professor at the Vienna State Academy. His personal life seemed settled, too. He had married a woman named Luzi von Sonnenthal, with whom he would have two children. In 1934, however, an offer came from the German film and theater director Max Reinhardt that dramatically altered the course of Korngold’s career: move to California and write music for films. Soon, Korngold was composing scores for such movies as A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Captain Blood, and Anthony Adverse. His lyrical and opulent style was well suited to the cinema, and much of what we associate with the sound of Hollywood’s golden age is the product of Korngold’s imagination. He was still essentially commuting, journeying between Hollywood and Vienna, but with the situation in Europe becoming untenable, the Jewish Korngold and his family settled permanently in California. He had signed on to score The Adventures of Robin Hood, starring Errol Flynn—a job, he later said, that saved his life, what with the Nazis annexing Austria in 1938 and branding Korngold’s music as degenerate.

By the end of World War II, Korngold, now a naturalized American citizen, had become frustrated with Hollywood and tried to resurrect a career in concert music and opera. He did produce one masterpiece: the Violin Concerto in D major, which incorporated many of his own film themes and which Jascha Heifetz popularized in a dazzling recording. (That record was my own introduction to Korngold’s music; I taped it off the radio when I was in high school and played the cassette to death.) But from the critics’ point of view, Korngold’s lush, unabashedly tonal idiom, which seems blithely ignorant of every spiky current of the 20th century, had had its day. The midcentury, after all, was the height of the avant-garde, of Pierre Boulez and the serial composers of the Darmstadt School. Korngold’s music belonged to another era—that of the Habsburgs, tonality, and old Viennese luxuriance. In October 1956, Korngold suffered a stroke. A year later, he was dead at the age of 60.

His concert music has, in recent years, undergone a renaissance. (His film scores never fell out of fashion. They are among the most beloved, celebrated, and influential in the genre.) And that first success, Der Schneemann, remains as gracious and effervescent as ever, shimmering, bright, and playful. Listen to only a few measures, and you will hear how thoroughly the young Korngold had absorbed the dance music of the Strauss family—Johann senior, Johann junior, Eduard, and Josef—and how well he understood the post-Romantic harmonic techniques of Mahler and Richard Strauss. The work’s extended serenade features a solo violin (a depiction of Pierrot wooing Columbine) in passages that are expressive and tender, Korngold exhibiting the gift for melodic invention that would later suit him so well in Hollywood. To be sure, some of the melodies are derivative, but there’s so much more here than mere mimicry. Korngold was not, in the end, the second coming of Mozart—or Mahler or Richard Strauss, for that matter. But you can hear in this early work the emergence of a mature artist, who would go on to write some of the most ravishing melodies of the 20th century.

Listen to the BBC Philharmonic, led by Matthias Bamert, perform Korngold’s Der Schneemann: