The Degradation Drug

A medication prescribed for Parkinson’s and other diseases can transform a patient’s personality, unleashing heroic bouts of creativity or a torrent of shocking, even criminal

It started with selfies. Hannah had never taken a selfie before, or even given the idea much thought. She was a tenured 39-year-old psychology professor at a New England college. But eight days after she started on pramipexole, a drug prescribed off-label by her psychiatrist for depression and anxiety, Hannah began taking photos of herself obsessively. She couldn’t explain the desire. At the time, it didn’t even seem especially strange.

Neither did the hats. She just felt like wearing them—or, really, any item that would cover her head. A gray wig. A red fedora. A spider-webbed fascinator. A vintage, canary-yellow beehive cap. Ordinarily Hannah was a modest dresser. But within weeks, she began ordering exotic clothing online, including flamboyant suits made for adolescent boys. “I had green velvet, red velvet, black velvet,” Hannah told me when we discussed her case. “I had my tuxedo. I had my plaids.” (To protect Hannah’s privacy, I have changed her name and some of the identifying details of her story.) Many of these outfits were impulse purchases. “Sometimes I could drop a grand in less than 30 minutes, waking up in the middle of the night to shop,” she said. One selfie from this period shows her wearing headphones, a short strapless dress, and a Batman mask. Men began to pay her a lot of attention. “I didn’t think to stop and analyze too much what was happening,” she said. “It was a constant rock ’n’ roll party in my head, and I was the star.”

Pramipexole, or Mirapex, was developed to treat Parkinson’s disease. As a dopamine agonist drug, pramipexole is believed to work by stimulating dopamine receptors in the brain that have degenerated. Hannah did not have Parkinson’s. She had struggled with depression and anxiety since she was 16. Along with Mirapex, which Hannah started taking in December 2014, her psychiatrist had prescribed a cocktail of psychoactive drugs that included lithium, Lamictal (lamotrigine), Xanax (alprazolam), and Provigil (modafinil). And the drugs worked. Hannah felt terrific. But patients on dopamine agonist drugs such as pramipexole can have trouble controlling their impulses—the impulse to gamble, to shop, to eat, to have sex. Hannah was never told of these potential side effects. She didn’t realize that her new personality might be chemically induced.

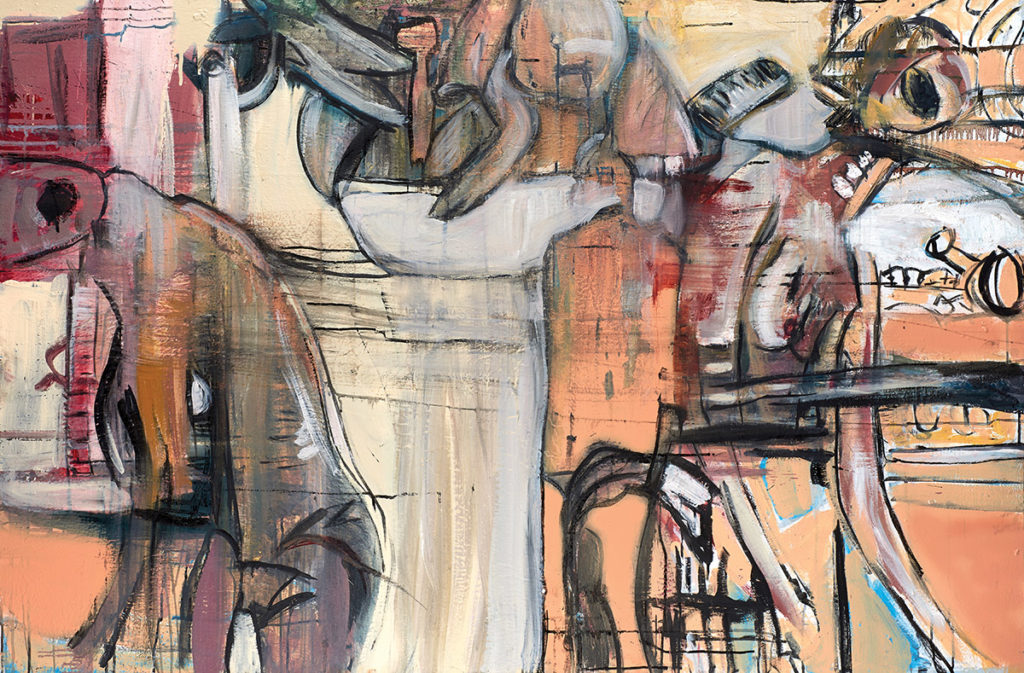

In July 2015, Hannah took a trip to Rome with her mother. Standing before Michelangelo’s Pietà in St. Peter’s Basilica, she had a profound religious experience that left her weeping. It felt as if a passage to a supernatural realm had opened up in her mind. Afterward, she began to paint nonstop, sending her bewildered mother out for art supplies. “One night in the hotel she caught me in the bathroom at three a.m., painting,” Hannah recalled. “I hadn’t gone to bed yet.” Within several months of her return to the United States, Hannah had rented a 650-square-foot commercial studio and was painting more than 18 hours a day, mainly large abstract expressionist murals. Critics and gallery owners began to take notice. “My mind was on fire,” she said. “It was pure compulsion. It had to be done.” She would pace around the studio listening to crappy pop songs, barking out nonsense syllables, filming herself compulsively.

The longer Hannah took pramipexole, the worse her behavior became. She picked fights in bars. She bought provocative clothes at a shop that sold outfits to streetwalkers. She wore a T-shirt that said “Fuck Cornell” and bought a gold necklace that spelled out B-I-T-C-H. She insulted friends and family members. She took a box cutter to several paintings by a close friend. She euthanized her cat on a whim. Her social media accounts were a disaster. “I would troll,” she said. “I would just point out: you’re a phony, you’re a hustler, you’re a hack, you’re a thief, without a second thought about what they were going to do to me.” Her driving became dangerously reckless. “I passed a double-decker bus going 80 miles an hour around a blind turn,” Hannah said. “I remember pulling over and crying, I was so scared.” But, according to Hannah, her psychiatrist saw the treatment as a clinical success. Beyond that, he was delighted by the critical acclaim her painting had earned. It was as if pramipexole had unlocked a dormant artistic gift, transforming a garden-variety depressive into the next Willem de Kooning.

Hannah’s suicide attempt came eight months after she started on pramipexole. She had run a literature search on dopamine agonists and become aware of their alarming side effects. It can be hazardous to discontinue such drugs abruptly, but that is what she did. Two days after she stopped taking pramipexole, Hannah walked into her bedroom: “I saw the belt. I saw the door. The idea came into my head: Hang yourself.” She went on, “I just remember that there was a mirror, and I’m hanging from the door, and I can see myself hanging. I didn’t realize you don’t get a warning when you’re about to lose consciousness. Boom. Lights out.” She woke up on the floor, disoriented, with a belt around her neck. Apparently she had not properly secured the belt and had fallen when it slipped off the door. She ran into the street screaming.

Hannah started taking pramipexole again. Soon she was not just painting but also performing for audiences in her studio, usually cross-dressed as a teenage boy. “In my mind’s eye, I was a male,” Hannah says. “He was striking. I mean, he got your attention in every way. Everybody wanted to be around him.” It was as if the drug had produced a new identity, she says. “The split was so clean. I was a professor, competent and professional, but when I left work, everything just exploded.”

I met Hannah in June 2019 at her home, a renovated red farmhouse in rural New England that smelled like freshly cut wood. She had contacted me several months earlier—knowing that I wrote frequently about unusual forms of behavior—and after several phone and email conversations, I spent a weekend talking with her. I also spoke with a close friend who helped her through her ordeal, and with two friends who knew her before she started taking pramipexole. When we met, Hannah was married, five months pregnant, and dressed in a blue frock. She looked nothing like the blank-eyed, cross-dressing artist in photos taken two years earlier. In the fall of 2016, she began to taper her pramipexole dose slowly downward over a six-month period without telling her psychiatrist. (The state medical licensing board disciplined the psychiatrist after Hannah filed a complaint.) The process of withdrawal was agonizing. But as the pramipexole gradually left Hannah’s system, her frenetic rage disappeared. She no longer felt any desire to wear velvet suits, a Batman mask, or a “Fuck Cornell” T-shirt. Nor did she have any wish to paint. By the time of my visit, she had been free of pramipexole and most of her other psychoactive medications for 18 months, but she was still trying to make sense of her experience.

Horrible, Horrible Things, 5′ x 4 ½’

by “Hannah” (courtesy of the artist)

Neurologists have known for decades that dopamine agonists can cause problems with impulse control. In his 1973 book, Awakenings, Oliver Sacks described the reanimating effects of L-DOPA, a chemical precursor of dopamine, on victims of encephalitis lethargica, a “sleeping sickness” believed to be virally transmitted. Many of the patients had been near-catatonic for years. One of them, a middle-aged, Harvard-educated man whom Sacks calls Leonard L., had an initial response to L-DOPA that was close to miraculous. Sacks describes him as “drunk on reality.” But soon his euphoria was accompanied by an insatiable libido. Leonard became a “wild, wonderful, ravening man-beast,” masturbating for hours on end.

Leonard did not really understand what had happened to him until the drug began to wear off. Similarly, some patients taking dopamine agonists say they had no idea that their behavior was problematic until they were arrested, bankrupt, or otherwise publicly humiliated. Even patients who might be expected to have insight by virtue of their education—medical training, for instance, or, as in Hannah’s case, a psychology degree—are often blind to their own pathological behavior. “Patients often deny impulse-control disorders on direct questioning, only for the spouse to reveal to the physician at a later visit that this has been going on for some time,” Anhar Hassan, a neurologist at the Mayo Clinic, told me. She believes that some patients truly lack insight, although it’s also possible that some are simply ashamed to admit to their compulsions. For this reason, it is hard to say exactly how often dopamine agonists lead people into legal or ethical trouble.

Yet case reports are not hard to find. According to a 2010 article in the journal Sleep, a grandfather who was prescribed the dopamine agonist ropinirole for restless legs syndrome gained 200 pounds from binge eating and had his home raided by the police for illegal sexual activity on the Internet. In 2011, neurologists in Buenos Aires reported a Parkinson’s patient taking pramipexole who “was found by one of his sons attempting to have sexual intercourse with a female family dog.” In 2016, a 54-year-old Oregon man taking a dopamine agonist for Parkinson’s was sentenced to prison for exposing himself to 15 women in three different cities while wearing a wig. Once off the drug, many patients are so ashamed of their behavior that they are desperate to keep it secret. As Hannah put it, “You’re a professor, and you’re middle-aged, and you have esteem, and you’re walking around in a prostitute’s outfit with the word bitch across your chest. You might as well put me on a leash and walk me like a dog. It’s total degradation.”

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first dopamine agonist (pramipexole) for Parkinson’s in 1997. To date, it has approved six dopamine agonists, not just for Parkinson’s but also for restless legs syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and two hormonal disorders (acromegaly, which is caused by excessive growth hormone, and hyperprolactinemia, which is caused by an excess of prolactin, a hormone that promotes lactation). Medical journals report that dopamine agonists have been prescribed off-label for, among other conditions, depression, bipolar disorder, fibromyalgia, and erectile dysfunction. Many patients are so devastated by Parkinson’s that they will risk a lot to alleviate it. But the risk-benefit calculation is much different for milder conditions. It is a rare case of restless legs syndrome that is severe enough to make the risk of prison time or the sex-offender registry look like a reasonable tradeoff.

The risks of developing an impulse-control disorder on a dopamine agonist are contested. Many estimates put that risk at between six and 17 percent. But a 2018 study published in the journal Neurology found that 46 percent of Parkinson’s patients taking dopamine agonists developed an impulse-control disorder over a five-year period. The risk is smaller with conditions that require a lower dose but can still be considerable. Some patients who try to stop taking dopamine agonists, as Hannah did, experience severe withdrawal symptoms. In 2016, citing the “devastating, life-altering effects” of impulse-control disorders, including “divorces, financial ruin, criminal charges, and suicide attempts,” the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen formally petitioned the FDA to issue its strongest “black box” warning about the risks—that is, a highlighted warning on the packaging that calls special attention to serious hazards. Two and a half years later, the FDA had neither granted nor denied the petition, citing the “complex issues” involved. Public Citizen filed suit to force a response, but in October 2019, the FDA denied the petition, stating in its decision letter that although “there is evidence dopamine agonists contribute to a biologically plausible mechanism, the role biological plausibility plays between dopamine agonists and [impulse control disorders] remains theoretical at this time.”

These problems go beyond dopamine agonists. Drugs like pramipexole and ropinirole represent only one example of a range of medical interventions that can produce profound changes in behavior and personality, from antidepressants and stimulants to procedures such as deep brain stimulation and transcranial magnetic stimulation. Some changes are desirable, of course, but most interventions can also carry disturbing behavioral side effects. As these interventions become more common, so will the philosophical and ethical issues we face—issues that go beyond the specific treatment for a specific patient.

Should patients such as Hannah be held responsible for their actions? If the drugs simply caused bad behavior in a reflexive, mechanical manner, like the Queen of Diamonds triggering the Manchurian candidate, the answer would be a straightforward no. But human psychology is complicated. People react to dopamine agonists in a variety of ways, and their actions aren’t always easy to forgive. When people on dopamine agonists commit criminal acts, American judges and juries are often reluctant to exonerate them. In 2011, a California physician taking pramipexole for restless legs syndrome was charged with sexually assaulting six patients. He was stripped of his medical license and sent to prison. What Mr. K did, the judge said of the physician’s behavior, “was unethical, immoral, and unlawful.” The medication, he went on, “answers a lot of questions” but “it doesn’t excuse anything.”

Despite the judge’s ruling, there are good reasons for arguing that the medication constitutes an extenuating circumstance, much as a demonstration of mental illness already does. Yet as methods of manipulating human nature grow in scope and depth, there is every reason to think that determining blame and responsibility will become harder, even as they take center stage in our criminal and civil courtrooms. The issues involved in these judgments raise profound questions about what exactly makes us who we are. And those questions remain morally contentious even without identity-altering drugs.

“I knew there was something so terribly wrong because this wasn’t the man I married.” That is how Elizabeth described her husband, Frank, after he began taking pramipexole. (Elizabeth and Frank are pseudonyms.) Before pramipexole, Frank was a faithful husband, professionally successful, the devoted father of two children. After a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis, he began having muscle spasms at night, for which his physician prescribed pramipexole. The drug helped with the muscle spasms, but it also transformed him. Frank started to monopolize conversations. He spent hours playing online poker. One day he went out to buy grass seed and came home with a new car. Five years after he started taking pramipexole, Frank was convicted of possession of child pornography. He had not become a pedophile. He had memories of being sexually abused as a child and was convinced that the abuse had been photographed or filmed. Tracking down the evidence of his abuse became an “all-consuming thought,” Frank recalled—a kind of “monomania.” He downloaded so much child pornography that he couldn’t even go through it all. Looking back at the episode, he thinks, “How could I not have realized my behavior was so bizarre?” At the time, however, it just felt like what he needed to do. When I asked whether he didn’t realize that he might wind up in jail, or that others would find his actions repulsive, he replied, “What other people thought wasn’t in my mind.”

“He didn’t care what I was doing,” Elizabeth testified at his trial. “He didn’t care what our children were doing. He just became so self-centered that what I could see is just a turning and caving in of himself to the exclusion of everything, including his job.” Although his plea of insanity was rejected, the judge gave Frank a relatively light sentence, accepting the argument that pramipexole had transformed him into a very different man. “What we do know, from everything, is this man’s personality completely changed,” the judge said. “We have 50 years of his life in front of us that is entirely exemplary.” When he stopped taking the pramipexole, his child-porn obsession vanished and his original personality returned. “He was the old Frank,” Elizabeth said. Jekyll-and-Hyde transformations like this run though many dopamine agonist stories.

Many of us would feel, intuitively, that it is wrong to blame such patients for their bad behavior. That intuition has two strands. First, if a dopamine agonist involuntarily transforms someone so dramatically that it seems you’re seeing two different people, it doesn’t seem fair to hold one person responsible for the actions of the other. Second, withholding a judgment of blame sometimes seems more appropriate if someone behaves in a way that is completely uncharacteristic or alien. When your husband seems more self-centered than usual or makes an unflattering fashion change, the new behavior might seem to fall within the normal range of variation. But when your husband, a stoic Presbyterian banker, abruptly begins to dress in drag and feed the casino slot machines, you will naturally suspect an external cause—even if your husband doesn’t feel the change himself.

In “A Lecture on Freedom of the Will,” Ludwig Wittgenstein imagines a thought experiment. “I am in a room, free to go wherever I please,” he writes. In the room below, a professor has a mechanism that he regulates with a crank. The professor says, “Look, I can make Wittgenstein go wherever I want.” The scene is easy to imagine: When the professor turns the crank to make Wittgenstein stand up, Wittgenstein stands up. When he turns the crank to make Wittgenstein pace back and forth, Wittgenstein paces back and forth.

Wittgenstein says that if you were to visit him in the room and ask whether he had been compelled to act or was free, he would answer: “I was free.” And if you hadn’t seen the professor with the crank in the room below, you would have no reason to disagree. You would treat Wittgenstein like any ordinary person. Yet once you have been made aware of the professor with the crank, it would be hard to see Wittgenstein in the same way. Your attitude toward him would shift. He would seem more like a puppet or a robot: a being for whom attitudes like blame and resentment don’t seem applicable anymore.

The late Oxford philosopher Peter Strawson would call this a shift from a “reactive” attitude to an “objective” one. Reactive attitudes are the feelings that we have toward one another in the course of ordinary social interaction, feelings such as resentment, gratitude, anger, and forgiveness. But when we suspect that someone is psychologically abnormal—say, a person who is delirious or psychotic, or just physically and morally immature, like a child—we typically shift over to the objective attitude. To take the objective attitude is to see the person as an object: someone to be managed, handled, trained, diagnosed, or cured. The objective attitude isn’t devoid of emotion. The emergency room physician examining a delirious patient might feel anger, amusement, or sympathy. Seeing someone in this objective way is not incompatible with fear, pity, revulsion, or even a certain variety of love. But it is incompatible with feelings such as blame and forgiveness.

To take the objective attitude is not to exonerate someone from blame and responsibility, at least not in the conventional sense. Rather, it is to say that the ordinary rules of blame and responsibility don’t apply. This is why we don’t try small children in court. Yet as anyone who has raised a child knows, it is not always easy to decide which attitude to take. Family members dealing with patients on dopamine agonists may feel a sense of genuine ambivalence. Should their attitude toward a person taking pramipexole be reactive, as it would be toward a person taking Prozac or Adderall? Or should it be objective, as it would be toward someone who had suffered some sort of serious brain damage?

With many patients, the drug is closer to brain damage. Their new behavior is uncharacteristic and otherwise inexplicable. The transformation is dramatic. What’s more, the aberrant desires that the patient experiences are often dose dependent and reversible: if the dose is increased, the desires get stronger and harder to resist; if the patient stops taking the drug, the desires vanish. It would be inhumane to hold patients in such extraordinary circumstances to conventional standards of blame and punishment.

When you’re accused of wrongdoing, as Oxford philosopher J. L. Austin wrote in his classic 1956 article “A Plea for Excuses,” you have two general ways of evading blame: a justification or an excuse. To justify an action is to admit that you did it while contending that it was the right or sensible thing to do under the circumstances. An excuse is when you admit that the action was wrong but argue that it’s not fair to say baldly that you did it. “I was pushed” and “I couldn’t see clearly in the dark” are both excuses, in that you are distancing yourself from the “doing” of the action. Distancing usually takes one of two forms: compulsion or ignorance. To plead compulsion is to say, “I couldn’t help doing it”; to plead ignorance is to say, “I didn’t know what I was doing.” To say that you acted under the influence of pramipexole is to claim a little of both.

Some patients describe urges so powerful that they succumb despite their better judgment. “It’s like not eating for four days and somebody putting a bowl of pasta in front of you,” Hannah said. “How long can you control it? I remember fighting with myself. ‘You can go outside without a hat on. You can do it.’ And you can’t do it!” A subset of patients find themselves afflicted by stereotyped, repetitive motor activities known as “punding”—weeding their gardens, sorting their jewelry, assembling and disassembling cameras or watches for hours on end. These actions have the flavor of full-blown compulsions. A 55-year-old woman taking Apokyn (apomorphine) for Parkinson’s disease, frustrated by her apparent inability to stop cataloging thousands of tiny buttons, described it as “like being on a merry-go-round.” Sometimes, Hannah said, her condition seemed like the opposite of paralysis: her body was moving even though she didn’t command it to. “I felt like I was in the back seat and somebody else was driving.” The experience has shaken her belief in free will.

The argument that some criminal impulses are irresistible hasn’t fared well in the courts, in part because it is so difficult to distinguish between impulses that are genuinely irresistible and those that are simply not resisted. Unlike human endurance, which seems to have physiological limits, there doesn’t seem to be a natural limit to our ability to resist a desire. English common law defines an impulse as irresistible only if a person would have done it “with a policeman at his elbow.” But that sets a standard that is nearly impossible to satisfy. Just about any desire can be resisted for a time if the threat of punishment is immediate and severe enough. As Flannery O’Connor’s Misfit says in the story “A Good Man Is Hard to Find,” “She would of been a good woman if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.”

Many patients describe the problem as less a battle against their worst urges than a failure to see anything wrong with indulging them. “I couldn’t resist, but also I didn’t care,” said Vicki Dillon, a nurse in the north of England who was prescribed ropinirole when she developed Parkinson’s at age 35. “I had no brakes, no morals, no inhibitions. There was no Jiminy Cricket sitting on my shoulder saying, ‘Vicki, no, don’t do that.’ ” Things got so bad that she and her family lived separately for a period of time. When Vicki stopped taking the drug, the old Vicki returned, and the couple reconciled. Marc Mancini, a former college professor in California, developed a pathological gambling habit on pramipexole. “You lose all sense of perspective,” he said. “Occasionally I’d pause and say, ‘What am I doing?’ But then I’d think, ‘It’s fun! How can it be bad?’ ” Within two years he had emptied his bank account, stopped paying his taxes, sold a $1.2 million house to cover his gambling debts, and spent down all but $10,000 of his retirement savings. He would have blithely plowed ahead if his daughter hadn’t finally stepped in.

A lack of perspective sounds a little like ignorance, but it sounds even more like the disinhibition—a symptom of frontal lobe syndrome—often associated with traumatic brain injuries, strokes, and dementia. Damage to the frontal lobes can impair the executive functions needed to plan rationally, to assess risks and rewards, and to weigh the present against the future. The most famous disinhibited patient in medical history is Phineas Gage, the unfortunate railroad man whose left frontal lobe was severely damaged in 1848 when an explosion drove an iron rod through his head. His personality changed so dramatically that his friends said, “Gage is no longer Gage.” Disinhibited patients are often impulsive, hypersexual, aggressive, and socially insensitive—a constellation of symptoms amounting to what the 19th-century Swiss physician Leonore Welt called a lowering of ethical and moral standards. According to the American Law Institute’s Model Penal Code, a person is not responsible for criminal conduct if he or she lacks the capacity to “conform his conduct to the requirements of the law.” If it is unfair to punish disinhibited patients whose executive functions are impaired by brain injuries, then the same, one may argue, should apply to patients impaired by dopamine agonists.

Criminal exoneration may not settle the issue morally, though, at least not for alarmed family members asking why their loved one has been transformed into, say, a compulsive flasher, rather than a compulsive shopper or gambler. Consider a patient with dementia who suddenly begins making racist remarks. Even if you want to be forgiving, you can’t help but wonder where the racism is coming from. This issue becomes especially delicate with the small number of patients on dopamine agonists who develop full-blown paraphilias, such as a sexual attraction to children or animals. Has a drug created those desires? Or has it merely revealed them?

Of course, the same question could be asked about the burst of creative talent that Hannah experienced while taking pramipexole. The connection between dopamine agonists and creative talents has been explored in the medical literature, and according to some patients, such creative experiences are not uncommon. Jackie Christensen, a writer and environmental health activist in Minneapolis, wrote two books while taking pramipexole for her Parkinson’s disease. Jean Burns, a former web developer, designed birthday cards, posters, and website graphics in Photoshop. If dopamine agonists can create aberrant compulsions for which patients don’t really deserve blame, it seems fair to ask whether they can also create artistic gifts for which patients don’t really deserve credit.

Yet many of these patients experience the creative impulse as very different from their alien compulsions. “I felt like the creative things I did—the writing, painting, those things—were part of me,” Christensen said. “It just took something to activate them.” Her compulsive gambling, however, seemed external to her identity—it felt like “something was taking over my body.” Hannah had a similar feeling about her art. “It might seem that I’m in denial, that I want all of the recognition for the art and none of the consequences for the drugs,” she said. “But I actually do believe this: that the darkness came from the pill but that the light was always mine.”

Other patients are ambivalent. Oliver Sacks describes a patient on L-DOPA who was of two minds about her strange new desires. Sometimes the desires felt alien and intrusive. At one point, she described being “possessed” by what Sacks calls a “mass of strange and almost subhuman compulsions.” Yet later she experienced different appetites and desires that she couldn’t so easily dismiss as being alien to her real self. They felt more like exposures, “confessions of very deep and ancient parts of herself, monstrous creatures from her unconscious.” L-DOPA forced her to face a version of the existential question familiar from horror movies. Does the werewolf bite transform you into something else, or does it unlock a primitive, degraded version of yourself?

It may take a while for our moral emotions to catch up with new technologies. When people on dopamine agonists come to themselves, they often experience a dark sense of self-loathing. “I feel ashamed,” Frank told me. “What the hell was I thinking?” Vicky Dillon can barely stand to watch a television documentary about her experience taking ropinirole. “I feel sick. It’s not me,” she said. The fact that such patients would never have behaved this way without taking a dopamine agonist doesn’t much diminish the self-loathing. Many still feel responsible.

Maybe this is to be expected. In a famous 1981 essay titled “Moral Luck,” the Cambridge philosopher Bernard Williams imagined a case where a truck driver has killed a child through no fault of his own. We wouldn’t hold the driver morally responsible, Williams writes. We wouldn’t blame him or try to have him punished. Yet we would expect him to feel differently about the death than a mere spectator would. If he treated the death of the child simply as an unfortunate event, like a natural disaster, we might suspect he was a sociopath. There is something special about his relationship to that death by virtue of his having caused it, even if he bears no responsibility.

Most normal people in such situations feel this. Often they are so deeply traumatized by their role that they must be persuaded not to blame themselves. Why shouldn’t people taking a dopamine agonist feel the same way? “I hurt people,” Hannah told me, tears welling in her eyes. “And whether a drug caused me to do it, I am the vehicle of pain for other people.”

The future is likely to bring many forms of technological enhancement that will complicate the question of whether people on certain medications are fully responsible for their behavior. In criminal law, we acknowledge the possibility of this state of affairs by allowing, for instance, the presentation of an insanity defense. As we have seen, certain drugs have unwanted behavioral effects for which patients deserve no blame. There will be more of them. Genetic manipulation of human beings lies some indeterminate distance ahead, but a day will likely come when people will be born with specific traits that are the result not of a random genetic lottery but of deliberate choices made by people other than themselves. Embedded digital capacities combined with artificial intelligence—very much on the minds and drawing boards of military researchers—may not only enhance what individuals can do but also be subject to software malfunctions over which individuals have no control. All of these developments—whatever the overall positive results, if any, may be—will also surely cause episodes of undeniable harm. Increasingly, the legal system will be called upon to confront them.

And not just the legal system. In ordinary life, we typically make do with commonsense assumptions about human psychology—that our choices are truly ours, that we remain the same people over time, that the inner lives of other people are more or less like our own, and that some aspects of human psychology lie beyond voluntary control. The prospect of individualized neurochemical alterations may undermine those assumptions in ways that are not immediately obvious.

For instance, in the 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Philip K. Dick introduced a mechanical device called the Penfield mood organ. It allows people to dial up precise emotional states, ranging from a “businesslike professional attitude” or a “six-hour self-accusatory depression” to “the desire to watch TV no matter what’s on it.” As Dick saw, we often forget just how much of ordinary human life is embedded within psychological and physiological responses that we do not fully control: what embarrasses us or makes us angry, who and what sexually arouses us, what causes us to be anxious or alienated or sad. It is precisely the involuntary nature of these responses that makes them feel like windows into the psyche of another person, a peek behind the curtain to a place beyond artifice and manipulation. What happens to human relationships when we harness those responses and put them under neurochemical control?

Hannah sometimes wonders how to characterize her strange story. At times she thinks it was a psychiatric adaptation of Pygmalion, with her physician playing Henry Higgins to her chemically enhanced Eliza Doolittle. More often, though, she thinks of Faust and his pact with the devil. Just imagine being offered an artistic talent beyond anything you ever thought humanly possible, Hannah says. At the time, it might seem very tempting, even at the cost of public humiliation. “Knowing what I know now, however, never in a million years would I make that deal,” Hannah says. “The devil always collects.”