Civil Warfare in the Streets

After Fort Sumter, German immigrants in St. Louis flocked to the Union cause and in bloody confrontations overthrew the local secessionists

In the early months of 1861—as the Confederate flag unfurled above Fort Sumter, as bands played and newly formed regiments paraded in towns and cities throughout the North and the South—two civilians sat disconsolately at the sidelines of the Civil War.

One had recently taken a desk job running a horse-drawn trolley line. He spent most of his days pushing papers, trying his hardest to concentrate on the minutiae of fare revenues and fodder costs, in an office permeated with pungent aromas from the company’s adjacent stables. The other man was a down-at-the-heels, small-town shop clerk who had come to the city in search of an officer’s commission. He camped out at his in-laws’ house, trudging around the city each day, fruitlessly trying to attract the attention of the local military authorities.

The trolley-car executive was named William Tecumseh Sherman. The luckless clerk was Ulysses S. Grant. Both—as unknown to one other, probably, as each was to the nation—had found themselves in St. Louis.

It was not yet Grant’s or Sherman’s Civil War in the spring of 1861. During this opening act, the two future icons were fated to watch from the wings, restless understudies awaiting their turn onstage. Yet the story that unfolded around them that spring in St. Louis was a struggle as dramatic—and perhaps even as decisive—as any that would play out at Shiloh or Chattanooga. It was also a struggle unlike what most Americans today imagine: columns of blue and gray troops clashing nobly on the field of battle. Instead, the fight for Missouri in the spring of 1861—the first real military contest between Union and Confederacy—was a civil war in the truest and rawest sense, resembling those fought in our own time in such places as Beirut and Belfast: gun battles in the streets, long-simmering ethnic hatreds boiling over, and wailing mothers cradling slain children in their arms. It was also quite literally an American revolution—but with a cast of heroes largely forgotten to history, and with the Unionists, not the Confederates, as rebels.

The leading city in one of the nation’s most populous slaveholding states, St. Louis was a strategic prize like no other. Not only the largest settlement beyond the Appalachians, it was also the country’s second-largest port, commanding the Mississippi River as well as the Missouri, which was then navigable as far upstream as what is now the state of Montana. It was the eastern gateway to the overland trails to California. Last but far from least, the city was home to the St. Louis Arsenal, the biggest cache of federal arms in the slave states, a central munitions depot for Army posts between New Orleans and the Rockies. Whoever held St. Louis held the key to the Mississippi Valley and perhaps even to the whole American West.

The city and its surrounding state stood at a crossroads between the cultures of the North and the South, between slavery and freedom, between an older America and a new one. The old Missouri flourished in the region known as Little Dixie, the rich alluvial lands where black field hands toiled in the hemp and cotton fields. The new one could be found in St. Louis, where block after block of red-brick monotony— warehouses, manufacturing plants, and office buildings—stretched for miles along the bluffs above the river. Each year, more than 4,000 steamboats shouldered up to the wharves, vessels with names like War Eagle, Champion, Belle of Memphis, and Big St. Louis. The smoke from their coal-fired furnaces mingled with the thick black clouds belching from factory smokestacks, so that on windless days the sun shone feebly through a dark canopy overhead.

Throughout the winter and early spring of 1861, the Union revolutionaries who would soon fight the battle for Missouri were preparing for the war in hidden corners of the city. They drilled by night in beer halls, factories, and gymnasiums, barricading windows and spreading sawdust on floors to muffle the sound of their stomping boots. Young brewery workers and trolley drivers, middle-aged tavern keepers and wholesale merchants, were learning to bear arms. Most of the younger men handled the weapons awkwardly, but quite a few of the older ones swung them with ease, having been soldiers in another country long before. Sometimes, when their movements hit a perfect synchrony, when their muffled tread beat a single cadence, they threw caution aside and sang out. Just a few of the older men would begin, then more and more men joined in until dozens swelled the chorus, half singing, half shouting verses they had carried with them from across the sea:

Die wilde Jagd, und die Deutsche Jagd,

Auf Henkersblut und Tyrannen!

Drum, die ihr uns liebt, nicht geweint und geklagt;

Das Land ist ja frei, und der Morgen tagt,

Wenn wir’s auch nur sterbend gewannen!(The wild hunt, the German hunt,

For hangmen’s blood and for tyrants!

O dearest ones, weep not for us:

The land is free, the morning dawns,

Even though we won it in dying!)

These men were part of a wave of German and other Central European immigrants that had poured into St. Louis over the previous couple of decades. By 1861, a visitor to many parts of the city might indeed have thought he was somewhere east of Aachen. “Here we hear the German tongue, or rather the German dialect, everywhere,” one Landsmann enthused. Certainly you would hear it in places like Tony Niederwiesser’s Tivoli beer garden on Third Street, where Sunday-afternoon regulars quaffed lager while Sauter’s or Vogel’s orchestra played waltzes and sentimental tunes from the old country. You would hear it in the St. Louis Opera House on Market Street, where the house company celebrated Friedrich Schiller’s centennial in 1859 by performing the master’s theatrical works for a solid week. You would hear it in the newspaper offices of the competing dailies Anzeiger des Westens and Westliche Post. You would even hear it in public-school classrooms, where the children of immigrants received instruction in the mother tongue.

Politically, too, the newcomers were a class apart. Many had fled the aftermath of the failed liberal revolutions that had swept across Europe in 1848. Among those whose exile brought them to Missouri was Franz Sigel, the daring military commander of insurgent forces in the Baden uprising—who, in his new homeland, became a teacher of German and a school superintendent. There was Isidor Bush, a Prague-born Jew and publisher of revolutionary tracts in Vienna, who settled down in St. Louis as a respected wine merchant, railroad executive, and city councilman—as well as, somewhat more discreetly, a leader of the local abolitionists. Most prominent among all the Achtundvierziger—the “Forty-Eighters,” as they styled themselves—was a colorful Austrian émigré named Heinrich Börnstein, who had been a soldier in the Imperial army, an actor, a director, and most notably, an editor. During a sojourn in Paris, he launched a weekly journal called Vorwärts!, which published antireligious screeds, poetry by Heinrich Heine, and some of the first “scientific socialist” writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. In America he became Henry Boernstein, publisher of the influential Anzeiger des Westens. Though he may have cut a somewhat eccentric figure around town—with a pair of Mitteleuropean side-whiskers that would have put Emperor Franz Josef to shame—he was a political force to be reckoned with.

For such men, and even for their less radical compatriots, Missouri’s slaveholding class represented exactly what they had detested in the old country, exactly what they had wanted to escape: a swaggering clique of landed oligarchs. By contrast, the Germans prided themselves on being, as an Anzeiger editorial rather smugly put it, “filled with more intensive concepts of freedom, with more expansive notions of humanity, than most peoples of the earth”—more imbued with true democratic spirit, indeed more American than the Americans themselves. Such presumption did not endear them to longtime St. Louisans. The city’s leading Democratic newspaper excoriated the Forty-Eighters as infidels, anarchists, fanatics, socialists—“all Robespierres, Dantons, and Saint-Justs, red down to their very kidneys.” Clearly these Germans were godless, too: one need only walk downtown on a Sunday afternoon to see them drinking beer, dancing, and flocking to immoral plays in their theaters—flagrantly violating not just the commandments of God, but the city ordinances of St. Louis.

Yet St. Louis was still officially slave territory. Indeed, it was here that Dred Scott—“the best known colored person in the world,” locals liked to boast—had sued for his freedom; here that his widow and daughters still lived in an alleyway just off Franklin Avenue. And Missouri as a whole still lay firmly in the political grasp of the Southern planters, the slaveholders, the aristocratic scions of old French colonial families. In early 1861, as their sister states seceded one by one around them, these men naturally assumed that it was they who would decide Missouri’s fate.

In January, the state had sworn in a new governor. Claiborne Fox Jackson was a poker-playing, horse-trading, Little Dixie planter who had once led armed Border Ruffians into neighboring Kansas to keep it from becoming a free state. Better just to let the Indian savages keep Kansas forever, Jackson had once said, since “they are better neighbors than the abolitionists, by a damn sight.” Officially he was neutral on secession. But in his inaugural address, he made his leanings clear: “The weight of Kentucky or Missouri, thrown into the scale,” could tip the balance nationally from the Union to the Confederacy. Should the federal government try to coerce the seceding states, the governor warned, “Missouri will not be found to shrink from the duty which her position upon the border imposes: her honor, her interests, and her sympathies point alike in one direction, and determine her to stand by the South.” (Judging by printed sources, Jackson seems to have been a man who spoke frequently in italics.)

Missouri’s Germans had been slow to unite behind Abraham Lincoln in the recent presidential election—the folksy rail-splitter held little charm for the acolytes of Goethe and Hegel. But support from intellectuals like Boernstein encouraged them: the editor, fast becoming one of Missouri’s top Republican power brokers, hailed his party’s nominee as “the man who will see his way through a great struggle yet to come, the struggle with the most dangerous and ruthless enemy of freedom.” Even national political leaders stoked the flames. No less a Republican chieftain than William H. Seward, visiting St. Louis while stumping for Lincoln, told an audience: “Missouri is Germanizing herself to make herself free.” (Frederick Douglass had already expressed similar enthusiasm: “A German only has to be a German to be utterly opposed to slavery,” he wrote.)

That fall, Missouri Germans flocked to join the semisecret political groups, known as Wide Awakes, that formed across the North in support of Lincoln’s candidacy. Capes! Torches! Nighttime parades! It was just like the good old days back in Dresden and Heidelberg. And woe betide any opponent who might try to heckle at a Wide Awake rally: “If he escaped unmaimed he was lucky indeed,” one local Republican wrote.

Although Lincoln lost Missouri decisively, the Wide Awake clubs did not disband after the election. In fact, they began arming themselves: not with torches now, but with Sharps rifles provided by certain unofficial sources in the East. (Some of the Germans’ new weaponry arrived hidden, appropriately enough, in empty beer barrels.) Under the supervision of General Sigel and veterans of the Prussian officer corps, they began their clandestine drills. St. Louis, however, was not a place where such things could be kept secret for long. By early March, Democratic papers carried reports of a terrifying new battalion known as the Black Jaegers—it sounded even more horrible in German, the Unabhängige Schwarzer Jägerkorps—allegedly so named because they would fight under a black flag, signifying no quarter to their foes.

The Jaegers’ foes, for their part, were not sitting idly by. The secessionists formed their own force of armed Minute Men—“the grimmest of German-haters,” Boernstein called them. Democratic newspapers fanned the flames more vigorously than ever against “the Red Republicans or Infidel Germans,” the “‘fugitives from justice’ of foreign lands, who by some trickery have become citizens of our country.” Ordinary Missourians used more direct language: along with the usual racial epithets, “Damn Dutch,” a corruption of Deutsch, became a term of abuse throughout the state.

The Minute Mean had their eyes set on the St. Louis Arsenal. Its present stores could equip an entire Confederate army: 60,000 muskets, 90,000 pounds of gunpowder, one and a half million cartridges, and several dozen cannon—in addition to machinery for arms manufacture, of which the South had woefully little. The lame-duck administration of President James Buchanan, displaying its usual strategic acumen, had initially left only 40 soldiers guarding this bounty. But as winter turned into spring and the plots and counterplots multiplied, the Arsenal’s greatest asset would turn out to be one very strange little man.

[adblock-left-01]

Captain Nathaniel Lyon of the U.S. Army could hardly have seemed a less imposing warrior. A slight, red-bearded Yankee, he was constantly sucking on hard candies, which clicked wetly against his ill-fitting dentures. Yet Lyon embodied, in his five-foot-five frame, nearly everything that Southerners loathed and feared. He was a man of fervent, almost fanatical, Republican antislavery beliefs, which he never hesitated to vocalize in his harsh, nasal Connecticut bray. It was not, he made clear, that he gave a damn about the slaves—in fact, he publicly professed himself “not concerned with improving the black race, nor the breed of dogs and reptiles.” No, it was mostly just that he hated the South; detested its authoritarian institutions; and tasted bile at the very thought of secessionist treason. Many tales about him circulated in the army. Perhaps the most famous was of the time at Fort Riley when the captain came upon one of his privates beating a dog: after knocking the soldier to the ground and kicking him in the stomach a few times, he made him get on his knees and beg the animal for forgiveness. To know that story was to know Nathaniel Lyon.

At the urgent behest of local Unionists, the War Department had dispatched Lyon in February at the head of a few dozen regulars to reinforce the Arsenal. Such a force hardly sufficed. Within days of his arrival, however, Lyon conferred with the leaders of the Wide Awakes and realized that they had thousands of men at their command, but few weapons, while he commanded just a few dozen men but had access to enough weapons to arm half of St. Louis. United, they could be formidable indeed.

An armed standoff —between the Minute Men and heavily secessionist state militia on one side, and the Arsenal troops and former Wide Awakes on the other—lasted through early April. Then came the momentous report of Sumter’s surrender on April 14. Now it was Governor Jackson’s turn to act.

On the very day that the news arrived in St. Louis, a Sunday, Jackson struck the most dastardly blow he could inflict on the German community: he sent police to enforce the blue laws. Squads of officers fanned out across the city, raiding saloons and beer gardens and driving the clientele into the streets. (Drinking establishments popular among “Americans,” such as the bar at the Planter’s House Hotel, famous for its mint juleps and sherry cobblers, were not disturbed.) It was quickly announced that English would henceforth be the only official language of state business, and that funds for St. Louis’s public schools were being reallocated to arm Governor Jackson’s militia.

“Not One Word More—Now Arms Will Decide,” the Anzeiger’s headline announced grimly. “Every question, every doubt has been swept away,” the article continued. “The Fatherland calls us—we stand at its disposal.”

One group of German women made a flag. They stitched it together out of heavy silk, with stars of silver thread. Across its red and white stripes they painted an inscription in gold letters: “III. Regiment MISSOURI VOLUNTEERS. Lyons Fahnenwacht.” “Lyon’s Color Guard” was a new unit under the command of Franz Sigel. The ladies presented their handiwork at an impressive ceremony with both Sigel and Lyon in attendance, as well as the entire regiment. Miss Josephine Weigel stepped forward and addressed the commander in their native tongue:

Herr Oberst Sigel! It is a great honor for us to present you with this flag, made by German women and maidens, for your regiment. . . .

In keeping with old German custom, we women do not wish to remain mere onlookers when our men have dedicated themselves with joyful courage to the service of the Fatherland; so far as it is in our power, we too wish to take part in the struggle for freedom and fan the fire of enthusiasm into bright flames.

Nor was this the only female contribution to the cause—far from it, in fact. Throughout the city, one St. Louisan reported, women and girls were wrapping gunpowder and musket balls into cartridges “as fast as their fingers could fly.”

Within days, 4,200 Unionist volunteers were mustered into federal service, all but 100 of whom were Germans. Forests of white tents sprouted on the Arsenal grounds. At dusk the light of cooking fires flickered among the encampments, while “all nooks and crannies sounded with German war songs and soldiers’ choirs,” Boernstein recalled after the war. The main thing, one recruit wrote, was that each man was “eager to teach the German-haters a never-to-be-forgotten lesson.”

Less visible maneuvers were also taking place at the Arsenal. Having issued his troops all the weapons and ammunition they would need, Lyon determined to send much of what remained out of harm’s way, to the Union troops mustering in Illinois. As a handpicked crew of men worked secretly to pack up the weaponry, Lyon had spread a rumor, via local barrooms, that a shipment of weapons from the Arsenal would be sent across the city in streetcars that night. Sure enough, at 9 p.m., a trolley convoy loaded with wooden crates rolled slowly up Fifth Street. Minute Men instantly rushed out of ambush, halted the trolleys, pried open the containers, and pulled out the guns: a few rusty old flintlocks from the Arsenal’s junk room. Meanwhile, down on the river, the steamboat City of Alton, her lamps doused and paddlewheels barely turning, slipped quietly from the Arsenal quay and up the Mississippi, with 25,000 well-oiled muskets and carbines aboard.

Throughout the rest of the state, however, the rebels were on the ascendant. On village squares, county fairgrounds, and fallow fields across Missouri, young men mustered militia companies to defend their state against the Yankees. They armed themselves with hunting rifles and shotguns, sharpened homemade bowie knives to a razor’s edge, and buckled on old swords cadged from neighbors who had fought in Mexico. Many years later one of these Missouri volunteers would pen a wry account—a parody of the Civil War memoir genre—of his company from the town of Hannibal. In his telling, the unit was little more than a dozen or so boys playing at war, fighting hand-to-paw combats against barnyard dogs and “retreating” headlong through the night from nonexistent Union patrols. But ex-Lieutenant Sam Clemens was viewing the past through the sentimental haze of a quarter century, not to mention through the satirical lens of Mark Twain. In the spring of 1861, the secessionist militias were in deadly earnest. A different volunteer, making his way from the far west of the state to join the rebel forces, stopped with his comrades at a wayside inn, where the landlord’s pretty daughter entertained them with “Dixie” on the piano. “I made a promise to her that I would kill two ‘duchmen,’” the young man recorded.

Over the next couple of weeks, the opposing forces in St. Louis performed an uncanny pantomime. Across the city from the Arsenal, secessionists set up an armed camp of their own in an area called Lindell’s Grove, formerly a park and picnic ground. They dubbed it Camp Jackson in honor of the governor, and before long, more than a thousand state troops had arrived, under Missouri’s militia commander, General Daniel Frost. These soldiers, Sherman later recalled, included many “young men from the first and best families of St. Louis.” Ostensibly, Jackson and Frost had assembled them for a regular militia encampment, just as might be done in peacetime. As at a typical antebellum militia gathering, a festive, even indolent atmosphere prevailed; young ladies came and went to visit their beaux, and mothers brought hampers of food to their sons. But in fact, the commanders were expecting more troops to assemble—and they were awaiting a much-anticipated gift from Jefferson Davis.

[adblock-right-01]

Late on the night of May 8, another mysterious steamboat docked in St. Louis, this one unloading cargo rather than taking it aboard. Perplexed longshoremen were summoned to the levee to help move some enormously heavy crates marked “Tamaroa marble”: material for an upcoming art exhibition, they were told. Actually, the crates contained two howitzers, two siege cannons, 500 muskets, and a large supply of ammunition, all recently confiscated by Confederate authorities from the U.S. arsenal down in Baton Rouge. As far as arms caches went, this wasn’t much, but it was a start.

Unlike Lyon’s ingenious trolley-car trick, though, the midnight shipment of “art supplies” was a lame ruse indeed. By midmorning, several of the longshoremen, who happened to be Germans, had reported the suspicious activity to the Arsenal commander.

Instead of being alarmed, Lyon seemed elated. For weeks he had thirsted for a chance to humiliate the rebels. But the state militia and Minute Men had not given him an opportunity. Jackson, though hungry for the Arsenal and its stores, could not attack while so badly outgunned and outnumbered. Without such provocation, Lyon and Blair had felt constrained from moving against Camp Jackson. After all, the officers and men there were officially state troops, and the state had not yet gone over to the Confederacy; indeed, the Stars and Stripes still flew above the camp.

So while the arrival of Jeff Davis’s four cannons and 500 muskets may not have given Jackson and Frost much additional firepower, it gave Lyon exactly what he needed: a pretext.

In the early afternoon of May 9, a handsome barouche with a black coachman in the driver’s seat pulled up to the front gate of Camp Jackson. Inside it rode a genteel old lady dressed in a shawl, a heavy veil, and an enormous sunbonnet. In her lap she held a small wicker basket. The sentries waved her through; clearly this was just a widow paying a visit to her militiaman son, and her basket must be full of sandwiches she had lovingly prepared for her dear boy.

In fact, the wicker basket held two loaded Colt revolvers. And if the sentries had peered under the old lady’s veil, they would have glimpsed something even more surprising: a bushy red beard.

Surely there must have been a hundred simpler ways to reconnoiter the rebels’ picnic ground. Nathaniel Lyon, however, was not one to pass up an opportunity for intrigue, and apparently thought his escapade would seem picturesque rather than ridiculous. Anyhow, his leisurely drive through Camp Jackson showed him exactly what he wanted to see: the mysterious crates from the steamer, still unopened.

Early the next morning, a horseman was seen galloping southward down Carondelet Road, on his way to the U.S. troops’ outlying encampments. By midday, columns of soldiers were marching through the streets of the city, converging on Camp Jackson. Boernstein, in a splendidly plumed Alpine hat, rode astride a horse at the head of his regiment. Isidor Bush marched in the ranks of privates. Herr Oberst Sigel, on the other hand, rolled along in a carriage behind his men: the first casualty of the day, he had fallen off his horse onto the cobblestones and hurt his leg.

For weeks, the city’s German press had throbbed with ever-purpler prose. “The North has awakened from its slumber; the earth shakes under the tread of its legions, and the South trembles,” exulted the Westliche Post. “The great goal of mankind—the demand for freedom—will rise ever more glorious and flow like gold in the heat from the fire of battle.” Two days before the advance on Camp Jackson, the editors had hailed “the uprising of the people in the Northern states”—that is, the tremendous surge of patriotic feeling and military enlistment after Sumter—as one of the greatest events in world history since the defeat of Napoleon. “This period will be called the second American Revolution,” they predicted. “It will . . . be able to turn the great principles enunciated in the first revolution into reality.” And thanks to the quick dissemination of news by steamboat and telegraph, this revolution would also spread across the Atlantic, so that “soon the cry of jubilation of the liberated nations of Europe will echo across the ocean, greeting us as saviors and brothers.”

Grant, still a humble civilian, stood across from the Arsenal’s main gate, in front of the Anheuser-Busch brewery, watching the troops file out. Sherman, on his way to the streetcar company office, heard people on every corner saying excitedly that the “Dutch” were moving on Camp Jackson. The streets were filling with people hurrying after the troops, swept along almost involuntarily, “anxious spectators of every political proclivity,” one witness wrote, “never doubting for a moment that if a fight should occur they could stand by unharmed and witness it all.” One big, bearded man, distraught at Lyon’s surprise attack, shouted, “He’s gone out to kill all the boys,—to kill all the boys!” Although a couple of Sherman’s friends urged him to come and “see the fun,” he hurried in the opposite direction, walking quickly home to make sure his seven-year-old son, Willie, had not joined the packs of schoolboys scampering toward the excitement.

With a soldierly precision that impressed the onlookers, Lyon’s regiments surrounded Camp Jackson on all sides. In the grove itself, there seemed to be little commotion and no sign of resistance. General Frost’s militiamen were outnumbered at least eight to one. Lyon, on horseback, surveying the scene with satisfaction, sent in an adjutant with a curtly worded note demanding an immediate surrender. Frost had little choice. He sent the adjutant back with a note acquiescing, under strong protest, to the demand.

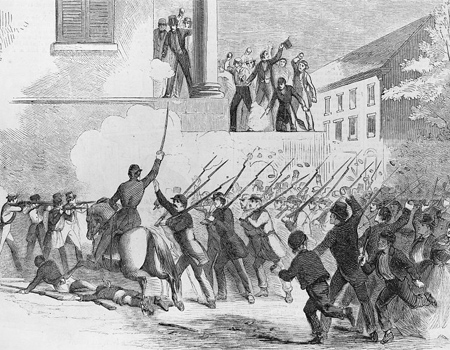

Lyon’s regiments drew up in formation on each side as Frost’s men began to file out through an opening in the fence. From all sides, crowds of civilians pressed in. Many were friends and relatives of the captured soldiers, anxious to see that their loved ones were all right; others had come to hail the Union triumph; most were probably just gawkers. Even Sherman, hearing that Frost had surrendered peacefully, now came to watch, holding young Willie by the hand. These spectators were amazed at the sight: militiamen in the splendid uniforms of Missouri’s most elite dragoon regiments; the flower of the old families—Longuemares, Ladues, Gareschés; the cream of St. Louis in “the beauty of youth, aristocratic breeding, clannish pride”—now captives, every one of them, stacking their arms in submission, trudging sullenly down Pine Street between the ranks of their drab Dutch captors. Two black women in the crowd, exultant, began laughing and yelling taunts at the humiliated militia. Soon other bystanders began hurling insults at the victorious Germans: “Damn Dutch!” “Hessians!” “Infidels!” One man cheered for Jeff Davis; another for Abe Lincoln. Lyon’s officers, trying to drown out the cacophony, ordered a brass band at the head of the column to start playing. Still the obscenities flew; women spat on the Union volunteers; others started scooping up rocks and dirt to throw at them. A few men brandished revolvers and bowie knives.

Afterward, no one could agree on how the shooting started. One teenager recalled seeing a boy his own age pitch a clod of dirt at a mounted officer. Other witnesses described an unarmed man stepping out of the row of onlookers and being savagely bayoneted by one of the Dutchmen. The most credible accounts corroborate what Sherman would remember. As he and Willie watched, a drunken man in the crowd tried to push his way through the ranks of Sigel’s troops to reach the other side. When a sergeant blocked him with his musket, shoving him roughly down a steep embankment, the drunkard staggered to his feet, pulled a small pistol from his pocket, and fired. An officer on horseback screamed as the bullet tore a gaping wound in his leg. (The captain, an exiled Polish nobleman named Constantin Blandowski, would die of his injury a few weeks later.) And so it was that the panicking soldiers turned their muskets on the crowd. Somewhere up at the head of the column, surreally, the German band kept playing.

Sherman ran back toward the grove, pulling Willie into a ditch and covering the boy with his body as they heard bullets cutting through the leaves and branches overhead. Around them people stampeded in all directions, some of them wounded. A few bold civilians stood their ground and fired back at the soldiers. By the time the shooting stopped, bodies lay everywhere: a middle-aged street vendor, a teenage girl, a young German laborer in his work clothes, and several soldiers from both Frost’s and Lyon’s commands. A wounded woman sat keening on the ground, the body of her dead child clasped in her arms. In all, more than two dozen people had been killed or mortally hurt. Lyon, dazed, stood looking around him, murmuring in a strange, soft voice: “Poor creatures . . . poor creatures . . . ”

Others stared almost as amazed at the sight of buildings pockmarked with bullet holes, like wounds torn in the city itself. Much commented on afterward was the remarkable power of the new minié rifle balls, how such small lumps of lead could make such big craters in brickwork and stone.

A 12-year-old boy, returning home with his father to Pine Street, saw something that would still haunt him more than six decades later:

Two bullets had struck our house, and just outside a German soldier was sitting on the side-walk with his back to the wall. Coming closer we could distinguish where the Minié bullet had penetrated his temple. He was dead. Close by a servant with a pail of water was washing a stream of blood off the side-walk where someone had been killed, and the sight to me was indescribably horrible. My father said this was civil war.

The retaliation began that night. Crowds of secessionists gathered in front of the Planter’s House as impromptu orators railed against the Negro-loving Republicans and Hessian mercenaries. At last the mob decided to wreck the Anzeiger print shop; storming down Main Street, they smashed the window of Dimick’s gun store and began grabbing shotguns and rifles. Fortunately for Boernstein’s paper, some quick-thinking Unionists blocked the street and fended off the attack with fixed bayonets. For the next 24 hours, though, Germans foolish enough to appear in public were chased down and beaten, stoned, sometimes lynched. One of the reserve regiments was ambushed by secessionists firing from behind the pillars of a Presbyterian church; in the ensuing confusion, several soldiers unlucky enough to become separated from their comrades were seized and executed with shots fired point-blank to the head. Rumors began reaching the city of similar reprisals across the state; in towns too small to have any Germans, Republicans were slain or “abolitionist” churches burned.

Meanwhile, in the wealthier neighborhoods of St. Louis, it was said that the “Dutch” were about to sack and burn the city. “The ‘upper ten,’ the rich, proud slaveholders,” as Boernstein called them, loaded up draymen’s wagons with mahogany furniture and chests of linen and fled by the thousands, crowding aboard ferryboats, seeking the safety of the Illinois shore.

But Captain Lyon’s sights were now set beyond St. Louis. He had accomplished everything he needed to do there.

Within a matter of weeks, Lyon, Sigel, and their German volunteers were marching toward central Missouri in hot pursuit of Governor Jackson, who by this point had unilaterally declared war on the United States and called for 50,000 volunteers to defend against Yankee invasion. (Boernstein and his men stayed behind to guard St. Louis.) Jackson fled Jefferson City at the troops’ approach, accompanied by most of the pro-secession legislature and the Missouri state troops. Lyon caught up with them 50 miles away, at Boonville, where he dealt them a quick but decisive defeat. After just a few casualties on each side, the state troops broke ranks and fled, hotly pursued by the German regiments, into the far southwestern corner of the state. Missouri would never again be in serious danger of falling into rebel hands.

Grant himself would believe for the rest of his life that but for Lyon and his Germans, the Arsenal, and with it St. Louis, would have been taken by the Confederacy. By seizing the initiative—by transforming the Wide Awakes into soldiers and moving against the secessionists before they could properly organize—the “damn Dutchmen” had sent their enemies reeling, never to regain their balance. In effect, a small band of German revolutionaries accomplished in St. Louis what they had failed to do in Vienna and Heidelberg: overthrow a reactionary state government. And they had done it in a matter of weeks, while in the East the armies were stumbling toward a war of attrition that would last almost four years. If Lincoln and his generals in 1861 had been more like Lyon and his Germans, the Union’s conquest of the South might have played out very differently.

But even swift victory did not come without a price. For the rest of those four years, Missouri would be the scene of atrocities unlike any seen elsewhere: ceaseless guerrilla warfare that erased distinctions between soldier and civilian almost entirely; violence with no greater strategic purpose than avenging the violence that had come before; in a few notorious instances, hundreds lined up and executed in cold blood. There would be many more shattered buildings, dead children and dead mothers, gutters awash in blood.