When we identical twins were growing up on a farm on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, psychologists would arrive from The-Lord-knows-where. They had driven across Chesapeake Bay to Chestertown, driven from Chestertown seven miles out Quaker Neck Road, turned down the wide dirt road of Johnsontown, and turned again to bump down our mile-long dirt lane to Comegys Bight Farm, where our father worked as the dairyman and where we lived. The psychologist would administer lengthy questionnaires to us individually, questions that I remember thinking were dumb. I’m sure I made up the answers but maybe they revealed my nascent personality anyhow. I tried to make my answers the opposite of what I thought my sister’s answers would be. I suspect her of doing the same.

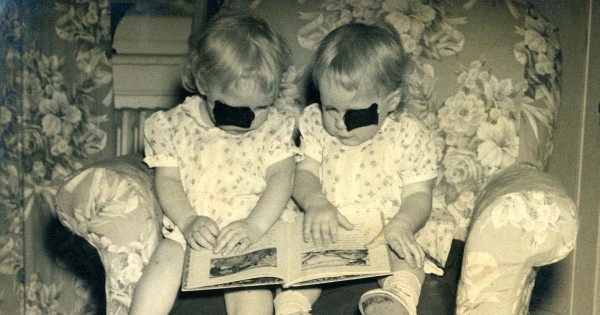

We liked being twins but strove to be as different as possible. Around age eight we refused to ever again dress alike. (A recent issue of National Geographic illustrated 20 pairs of identical twins, of which 18 were dressed like duplicates. Whose fashion idea was this? Is the choice of a T-shirt genetic? Come on.)

According to Nessa Carey in The Epigenetics Revolution, 10 million pairs of identical twins are alive today. In other words, to be an identical twin is not all that strange. Like all identical twins, my clone and I began as a single fertilized egg. This zygote, a single cell, begins to multiply and becomes a blastocyst. A blastocyst is a blob of about 100 cells, which become the fetus, surrounded by a circle of other cells, which become the placenta. In the case of identical twins the blastocyst splits in two and grows into two genetically identical infants.

But the big news is that having identical genes does not make you identical. Identical twins can be up to 12 percent different. This being the case, the term “identical” has been replaced by “monozygotic.” The difference is caused by epigenetics, which is, in Carey’s words, “the set of modifications to our genetic material that change the ways genes are switched on or off, but which don’t alter the genes themselves.”

Genes are rows of base pairs within DNA that provide the code for the production of proteins within the cell. Genes in liver cells express proteins that do the work of the liver; genes in skin cells or eye cells express proteins that do the work of the skin or the eye. So, what causes certain genes to turn on in one cell and stay off in another? Why don’t we grow eyes on our fingertips? After all, each cell in our body contains our entire genome.

The answer is that some genes code for proteins whose job it is to lie down on a gene and keep it turned off. Other genes code for proteins whose job it is to enhance transcription—the first step in making a protein. This regulation of gene expression is epigenetic.

The epigenetic process is influenced by chance and by the environment and produces what is known as clone discordance. For example, if you drink way too much alcohol (environment), the genes in your liver cells express more and more of a protein called dehydrogenase, which breaks down alcohol. This is why heavy drinkers can hold booze that would make a nondrinker fall drunk to the floor. Other examples include diseases that involve gene expression, chance, and environment (many cancers, schizophrenia, etc.). These diseases can fell one monozygotic twin and spare the other.

Carey encourages us to think of DNA as a script, rather than a template. With a template you stamp out identical gingerbread cookies. With the same script you can make two very different movies. My monozygotic twin and I, whether because of environment, predilection, or epigenetic switches, are two very different movies.