A few months ago in my adult pre-intermediate class, we started a new chapter in our textbook that was set up around a murder mystery. First, we discussed the vocabulary of crime, handy in all kinds of real-life situations, whether talking about recent shocking occurrences reported on the news, or about a favorite TV detective show, or about how mad you were at your daughter for leaving her wet towel in a heap on the floor. The students practiced the new vocabulary, including burgle and rob, steal and murder. By chance, it was the first day of Donald Trump’s hush-money trial, but we barely touched on that because the new vocabulary wasn’t extensive enough to cover all the crimes Trump was, or could be, accused of.

Then came the murder mystery. The students would hear an audio recording of two people talking on the street in the English village of Yately. Afterward, they were to identify the speakers from a cast of six characters presented in the book and then match all six names with the correct descriptors. This they did, identifying the two speakers as Mary, a village newcomer, and Alice, the owner of the corner flower shop, then the other characters: two business partners, the wife of one, and their son, Adam. In the audio, Alice tells Mary the big news: there’s been a murder! She drops in some gossip, namely that the victim, a married man, had been planning to leave his wife, who was distraught because her marriage provided the only joy in her life, especially since the couple’s son had been sent to prison for theft.

Then the task. The four students were to speak in pairs about who might have committed the crime. They didn’t have much to go on, but that was okay, they were game. I would listen in to both conversations, making quick corrections or taking note of common errors to point out later, for the benefit of all. Of the four students, one is a 50-year-old teacher and another a 30-something lawyer. The teacher practically smacks her forehead at a correction that reminds her again of what she already knows about verb tense or the pronunciation of a word with a silent letter. She appears equally annoyed at herself for making the error and at me for pointing it out. The lawyer squints and frowns as he searches for the exact word he wants.

The other two are young adults, one a computer programmer and the other a history student. The student is the youngest of the four, and his English is the best. His manner is calm and precise. When I correct him, he pauses almost imperceptibly before giving the smallest nod to signal that he has understood and absorbed my point. The programmer’s English is the worst, and he stutters and twists in his seat when he speaks. He practically writhes, giving a very convincing appearance of confusion and embarrassment. His thought process, however, is anything but confused. I think of him as someone who is locked-in, full of observations and insights but with no way to communicate them. His trouble with the language, his eagerness to succeed, and his auburn hair and creamy, freckled skin all contribute to a boyish mien. Beside him, the history student, who delivers his careful answers in a low tone, seems oddly mature. It’s an interesting group. Who, among the four, do you think will solve the murder mystery? The schoolteacher with her years of experience reading parents and children? The lawyer with his habit of sniffing out the truth? The student because he has the language skills to quickly evaluate the clues offered in the book? Or the programmer with his evident intelligence and energy?

Before making the first stab at guessing the murderer, the students listened a second time to learn when the murder occurred, where the body was found, when the new Yately Garden Centre had opened, what the two owners were arguing about the day before the murder, how the victim was killed, why the son, Adam, was sent to prison, and when he was released. That accomplished, I had the students review the information to make use of relative clauses: the man who, the place where, and so forth. “So,” I asked the students, “Who committed the murder and why? Talk with your partner.”

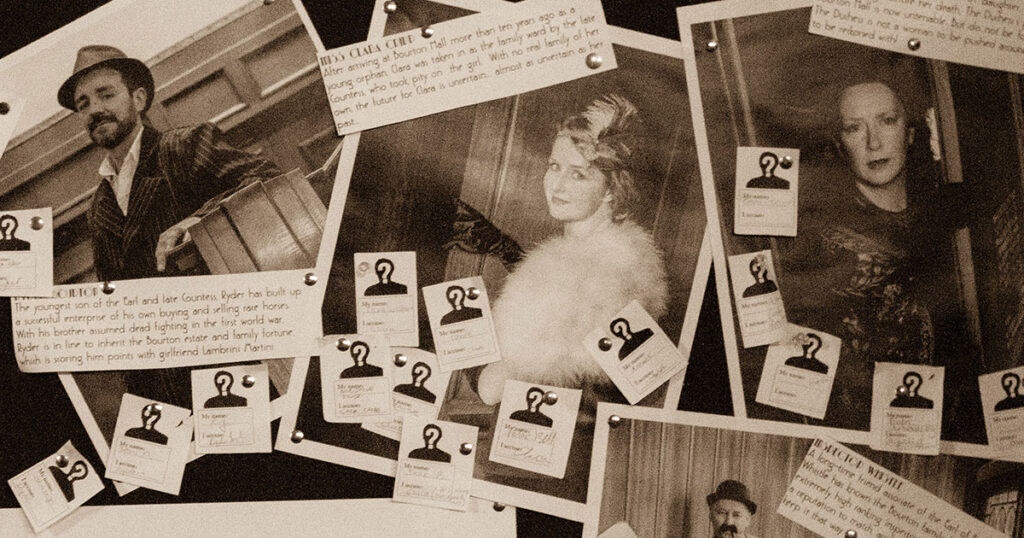

It was 7:40 in the evening. I glanced over the head of the programmer, seated with his back to the window. The sky was still blue but washed out at that hour of approaching dusk. Lights were on in the apartments across the street. A woman stepped out on her balcony, a cell phone in her hand, but she wasn’t talking, only holding it as she leaned on the railing to gaze into the street below. I turned my attention back to my students, concentrating with their partners on the murder at hand, books open before them instead of a detective’s dossier, a whiteboard on the wall instead of a bulletin board pinned with notes on the case. The students accepted the premise that to talk, you need something to talk about. These adults were better at entering into the spirit of such an exercise than are many other, younger students, especially the teens, who, despite their rebelling or scoffing or reticence, still worry about looking foolish. I loved that these four people, after their long days working or studying, would put their minds to this game of make believe. “Well?” I asked.

The programmer, with some clumsy phrases and some clever pantomiming, suggested a motive and a murderer. The others were more circumspect. “Maybe,” was as far as they would venture.

“Let’s look at the evidence the police turned up,” I suggested, and we continued on to the next exercise, which in the form of some hotel receipts with time stamps, a rose, and a black button, provided proof for the programmer’s theory. Yes, they all figured it out, but the programmer said it first. So three mysteries were solved: who killed the victim, who was able to guess, and how an hour-long class can pass in half that time.