Plucked from the Grave

The first female missionary to cross the Continental Divide came to a gruesome end partly caused by her own zeal. What can we learn from

I remember a particular autumn, when I was a girl in the late 1970s, traveling from Boise, Idaho, toward the town of Moscow. There were four of us in the car on our way back to school after vacation, returning to a state institution that our parents were certain would reinforce, would maintain, the western ideal in which we’d been raised. We drove the switchbacks of White Bird Hill and, some miles later, the twisty turns of Lewiston Grade. I crossed my arms over my stomach, closed my eyes, and held back the queasiness that inevitably came upon me by anticipating the flatter landscape ahead—over the last pass, I knew, lay calmer ground, the variations of yellow, the textures, the subtle relief of the stretch of land known as the Palouse. The North Idaho edge of the Palouse, that is, with its far edge in Eastern Oregon: a region of subtle humps and hollows formed in the last ice age and made fertile from a glacial silt known as loess, soil that’s ideal for the dryland farming of acres and acres and endless acres of wheat.

I was not yet 20 while on this drive, not at all worldly, far behind my contemporaries, I’m certain, in other parts of the world. I was a young woman who’d been born and raised in Idaho, who was permitted to apply to only this university (which my parents and grandparents had attended as well); who couldn’t grasp, I realize now, the dream of a life other than the one prescribed by the time in which I was living, my place, my people. I’d rarely left the state, unless I can count the travel made possible by books, and in that case I departed regularly. In a freshman English class, I’d read, for instance, Hemingway’s short story “Hills Like White Elephants.” I had only a hazy notion about the terse discussion between the man and woman in the story, more enthralled with the geologic mounds that appeared in the distance of their conversation. The great restless beasts looming over their dark quandary. Driving into the Palouse that autumn day, I sat in the back of my friend’s car, having begged for a ride because my father forbade me from bringing my own VW bug to college (a car, he said, would lead me into trouble). I stuck my head out the window, with Steely Dan’s “Hey Nineteen” on the tinny stereo, and gazed at the rolling treeless hills of the Palouse. Not like white elephants these, but like brown women. Open, vulnerable, sexual, though those weren’t words I could have applied then to the rise and fall of the hips, the goddess thighs, the swooping breasts, the angled shoulders of wheat crops. I knew only that the waving grasses—stunningly golden—trundling to the horizon both excited and released something in me, as if a switch had been turned that allowed me a glimpse of possibilities that were tantalizing and forbidden at the same time.

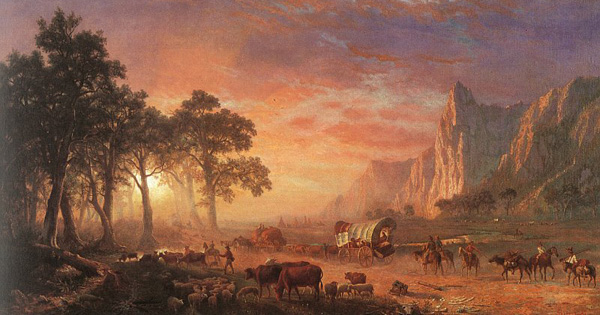

The first woman of European descent to settle in the Palouse—the first white woman, like the women of my family, like me—was Narcissa Prentiss Whitman. On July 4, 1836, she and another missionary wife named Eliza Spalding, along with their husbands and a contingent of guides, reached the apex of the Continental Divide, at South Pass in Wyoming, with a wagon full of household goods, including her precious trunk, a small piano, bolts of cloth, and pretty dishes—and walked to the other side. This moment, according to journals the women left behind, wasn’t one marked or celebrated in the moment, but simply regarded as another difficult mile on this more-difficult-than-they-could-have-imagined trek, which had begun in upstate New York nearly five months earlier. But the crossing soon became momentous—word quickly reached those east of the Mississippi that women had not only passed over the jagged and untamed Rocky Mountains, but had done so with a wagon, and a long pent-up desire to move west burst into the phenomenon known as the Oregon Trail. Within a few years, tens of thousands of women and wagons—and men and children and dried goods and animals and furnishings—headed off to begin again in a startlingly new, mysterious, and distant land.

My own pioneer ancestors were among those who sought new life in the West in the 19th century, and in this way, tenuous as it is, I consider myself linked to Narcissa Whitman. She, especially in the wake of her violent death 11 years after her arrival in the West, was regarded as a hero by people like mine. A tireless martyr, an “angel of mercy.” With her journey and her settlement in the far reaches of the West, she opened a door of sorts that my great-great-great-great-grandparents strode right through. These relatives also shared plenty of her attitudes about the frontier: an assumption that the land out here was theirs to claim, to take as their own by divine right; a determination to stay put, to grow crops and animals, to bear children and teach them to be fiercely loyal to one place. They believed in the divide between women’s work and that of the men. A way of thinking that remains, even now, at the core of my family’s sense of itself.

It’s curious to me that Narcissa’s primary aim was not to pave a path for the onslaught of new westerners. Instead, she felt she’d been called by God to save the godless creatures living on the far side of the continent before the Indians were exposed to the vagaries of the inevitable settlers. I try to imagine the drive stirred in this young woman: a spiritual awakening at the age of 11 potent enough that she became compelled to give up every comfort, her home, the family that cherished her. She had a certainty in her heart that allowed her to believe pagan strangers in the forests of the wild would bend in gratitude at the message she’d come to deliver. She thought if she could only teach the “savages” the ways of civilized white people, they’d assimilate into the settlement of the frontier. Narcissa could have easily stayed in upstate New York, become a teacher as her parents hoped, and married a kind New Englander, famous as she was for her singing voice, like an angel’s, and her beauty, her pious nature, her long strawberry blonde hair. Instead, she arranged to wed a man she’d only met once, twice at most, a man equally consumed with the missionary spirit. Marcus Whitman and Narcissa Prentiss each provided the other the means to travel to virgin country—the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions would consider only couples, not individuals, for the western trek. Narcissa departed with her husband a few hours after the ceremony, still wearing her black bombazine wedding dress, for a destination so frightening that no other missionary couples would accept the challenge. The others opted for Hawaii, for Guam, for anywhere but the dark and dangerous West.

In September of 1836, Narcissa, newly pregnant, along with Eliza and their husbands—Marcus Whitman and Henry Spalding—reached what was known as Oregon Territory, a tremendous expanse of geography, and began to plan the locations of their respective Protestant missions. The Spaldings went on to what’s now Idaho, near current-day Lapwai, to live among the Nez Perce. The Whitmans set down on the grasslands of the Palouse—outside the town later called Walla Walla, about a half day’s travel from one of the West’s first forts and smack in the middle of Cayuse Indian land. This was the tribe the couple would try to convert to Christianity, though in the end not one Cayuse Indian signed on to the Whitmans’ religion—the tribe did not care for the Whitmans’ inflexibility regarding spiritual practices; they certainly did not like that, although Marcus Whitman claimed to be a healer, vast numbers of their people were dying of new diseases that seemed to have no cure; most of all, the tribal members could not accept the missionaries’ constant threats of an eternal and fiery hell.

Tribespeople the Whitmans settled among didn’t refer to themselves by the name Cayuse. That word derives from the French cailloux, meaning “people of the rocks,” and was used by French trappers. (The origin of the word palouse is French as well: pelouse, meaning “land with thick grass.”) The Cayuse referred to themselves as “the superior people.” They lived on land they identified not as rocky, but as grassy: Waiilatpu—“place of the rye grass people”—and they relied on this bulrush, known also as tule, for their baskets, some of their clothing, their longhouse dwellings. The Whitmans, for the decade plus one year that they lived in this place, also called their mission “Waiilatpu”—their one concession to the native language—though Marcus cleared and burned the grasses around the compound in order to introduce the Indians to the plow, to dig irrigation ditches, and to make way for expansive gardens that would feed his family and a growing number of white pioneer visitors. He yanked up the rushes and planted wheat, built a mill. In her writings, Narcissa, without a flinch, and believing she was correct in excoriating the Cayuse for a belief system she’d traveled all that way to fix, refers to the Indians as “heathens” and “savages.” She once wrote that they “have been serving the devil faithfully,” apparently feeding the need in herself to make these people just that desperate for redemption.

[adblock-left-01]

Despite her single-mindedness, her severe tunnel vision, I have fallen into a fascination with Narcissa Whitman over the past few years. Part of my intention is to seek hints of my younger self in her younger self—to draw a line of sorts from her to me, from the first Caucasian woman to settle down in the West to those of us still here, deeply rooted in the attitudes that came with her, 162 years after her death. I’m not personally taken with her fervent evangelism, which met a bitter end, but I am drawn in by her zeal to give up everything she knew and loved to set off on an unprecedented journey, the first woman to do so. I wonder if she understood that she’d unwittingly provided a course and a rationale for thousands of pioneer women, including the ones I’m connected to five generations back. I’ve read her journals and letters—chock full of praise for her Lord and the fanatic determination to turn souls in His direction. But at times, under the thick layer of hallelujahs and amens, I’ve also detected a tender vulnerability—a yearning for her mother’s “pork and potatoes,” a plea for one of them, any of the ones she’d left behind, to please come to Oregon and ease her loneliness. In other words, she was complex and conflicted. Human. Reading Narcissa’s language, the beat of her own syntax, it occurs to me that she was in over her head before she’d left St. Louis. I wonder if she’d made a choice she wasn’t so sure of anymore—traveling with a relative stranger into utterly unknown territory—and, rather than turn back, she took to shouting louder about God’s intention for her life every day of the trip, every day of the 11 years at the mission. Putting together the numerous accounts of her life, it seems she grew more hardened by disappointment the longer she stayed in Oregon Territory, and, after the accidental drowning of her only child, two-year-old Alice, Narcissa became as impenetrable as stone.

Last summer, I asked to examine a rare book about Marcus Whitman, one volume within the vast holdings of the library of the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts. I’d applied for a research fellowship at the library because I wanted to dig around in this question: who was the real Narcissa Whitman? Not the myth, not the icon, but the actual woman who might teach me something about the women who followed her west, who might reveal to me my own calcified inclinations, bred into me through five generations of western women and men. I’d started my research some months before at Whitman College in Walla Walla, where a lock of Narcissa’s hair, set in a simple frame, rests chillingly atop a filing cabinet in the basement archives. In the college library, located a scant few miles from the Whitman mission at Waiilatpu, I sat at a table while the young archivist gingerly slid a set of her letters from a sturdy box. These letters were written on the journey out to Oregon Territory and, later, from her new home, her fine, straight handwriting barely decipherable on original paper that’s now turned crisp and yellow. In every one, she expounds upon her Christian duty to save the heathens of the frontier—even toward the end, when she and Marcus both suspected that they were in danger from tribesmen who’d grown angry and disenchanted with the missionaries, when her hopes were dashed and plans crushed, her life threatened—she vehemently defends her unyielding sense of right and wrong.

Once I arrived in Massachusetts, I began to read books about the people who had, it seems to me, swept in to take advantage of Narcissa’s death, as well as Marcus’s death and the deaths of others on November 29, 1847, at the mission. Fourteen people were killed by the Cayuse that day and another 50 taken hostage, precisely as the movement to get a government launched in Oregon was at fever pitch—reformed mountain men now aiming for a sheriff’s badge or a legislative seat joining early settlers to push for laws and regulations to enhance their property holdings and a burgeoning commerce. The timing was uncanny. White people were killed at Waiilatpu, violence was translated into fear, and fear was transformed into governance in an astonishingly brief period, and all under the great big cloud of Manifest Destiny. Out of Narcissa’s end came laws that increased the rights of white settlers, that provided justifications for killing native people and taking their land. Narcissa was instantly cast as an innocent martyr, and the complicated woman she was—a lonely woman, a woman who wanted to serve God only under her own terms, a woman who’d surely contributed to the conflict that led to the murders at Waiilatpu—was simply swallowed up.

One book I’d asked for at the American Antiquarian Society Library was delivered to a small carrel, as was protocol, and I set it on a dustless plastic cradle, more protocol, and squeaked open the cover that had, based on stiff and unblemished paper, remained unopened for decades. Peeling away the stuck-together pages, I found a blue piece of paper tucked into the middle of the spine—onionskin thin, extraordinarily delicate, and maybe six inches by four. The note was folded in half: I unfolded it. I held the paper in my palm and, I have to admit, my hand trembled a bit. On one side was pressed a feathery green leaf in the shape, nearly, of a Christmas tree. On the other side of the dried vegetation, written in the leaf’s rusty shadow, was this notation in tiny and formal handwriting: “Plucked from the grave of Eliza Whitman, October 12, 1848.”

That line both exhilarated me—what a thing to discover so far from my home, so far from her home—and rubbed me wrong, for these two women, Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding, had hugely different ways of being in the world, and of coping with the challenges and difficulties of missionary life. Documents left behind regarding Eliza’s sojourn with the Nez Perce describe her calm demeanor, her placid presence. She, too, was deeply religious—but she’d been willing to learn the Nez Perce language, and she’d accepted some of their ways as her own. Eliza made concessions around Nez Perce religious practices, formed friendships with many people in the tribe. Her life had not been threatened. The leaf on the paper in my hand had been picked from near Narcissa’s resting place, not Eliza’s (particularly since Eliza lived some years past 1848). It was the fierce and determined Narcissa who’d died at the hands of those she’d come to save. Seeing her name mixed up with another’s so soon after her death—not even a year—filled me with an odd frustration, a sadness that she had been quickly forgotten, already confused with a different person instead of remembered for the distinct force, confounding as the force may have been, that was Narcissa Whitman.

I abandoned the reading of the book that day in the library and concentrated instead on the piece of ephemera that had fallen into my hands. Since the library provided the means to do so, I tracked down the donors: Edwin Marble and Harriet Chase Marble, born in 1828 and 1830 respectively, which would have made them teenagers when the note was written. Was it one of them, or perhaps one of their parents who’d gone out to Oregon Territory in the late 1840s? This was my first question, the reason for an easterner to stand at the heap of soil over the mass grave of people who’d been killed 11 months earlier. There was no marked grave at that time. No place of internment for Narcissa. Her remains, which had been dug up by animals, were combined with the body parts of the others who’d been killed, all of which were hastily reburied in a shallow hole and covered with a wagon bed, topped with dirt. Waiilatpu in October of 1848 was nothing like the tourist attraction it is today, with tidy displays, a well-marked gravesite, a memorial atop a hill, and, on the valley floor, white lines painted in the golf course-like grass showing the shape and sizes of the mission’s buildings, weirdly reminiscent of the boundaries painted around a dead body at a murder scene. In October of 1848, the war the new government of Oregon had declared on the Cayuse was raging, the Cayuse, despite clever tactics, were losing, and their people hidden in the mountains were half-starved, aching for their land and their way of life. A few local mountain men—Joseph Meek, Robert Newell, Wesley Howell—had stormed onto the mission grounds not long after the killings to help with the reburying of the dead and to pick up pieces of Narcissa’s strawberry blonde hair, strewn across the quiet compound, one strand of which now sits atop the filing cabinets in the Whitman College library archives.

Who else besides the military and these rugged men would have cause to visit the scene of death? Some ancestor of the Marbles? Why would that person tear a leaf from a plant growing in the rubble, carry it all the way home, and press it flat? And why did this person, who went to the trouble to place the folded note into the book, and not just any book but one about Marcus Whitman, a book that happened to be owned by a family in Massachusetts that would put the volume away, undisturbed, for 160 years—why would this person conflate the two women’s names?

[adblock-right-01]

Perhaps whoever penned the note was thinking of young Eliza, daughter of the Spaldings, who’d been in residence at Waiilatpu during the attack. Nine years old, she emerged from the violence and was returned to her mother eerily unscathed—two of her closest friends lay dying of measles during the month following the killing spree but she managed to evade the illness; she was a few years too young to be considered “wife” by the Cayuse men, which saved her from being raped, as several teenage girls were. She’d watched Marcus die of a tomahawk embedded in his brain; Narcissa shot once in the breast, fired upon again and struck in several places on her body, then (so loathed was she by the people set on ending her life) dragged through the dirt and whipped by a leather quirt in front of the compound’s children as she moaned in pain. Eliza had witnessed the deaths of two teenage boys—Frank and John Sager—whom she’d also come to know well. Frank’s throat was cut and a piece of cloth stuck in the wound to delay his death and increase his suffering; John was dragged down from a hiding place in the schoolhouse and shot dead in front of his sisters. Eliza and the other children were made to walk out into the meadow the day after the dead were buried to regather body parts dug up and strewn about by animals. Eliza made it out alive, yes, but like the other survivors she spent the rest of her life reliving the images of November 29, 1847.

The same images—laced with a long and terrible anger that had built up in the Cayuse in regard to the Whitmans and toward Narcissa in particular—were sharply on the minds of those set on white settlement in Oregon Territory. Once the survivors were rescued, a month after the initial violence, a brand new government militia set out after the Cayuse. Not just the ones who did the killing, but every person related to the Cayuse tribe. Soon the tribe was decimated to the point that not a single full-blooded Cayuse Indian is alive today.

I was unaware of this history when I drove over the mountains to Walla Walla, Washington, one weekend during my senior year of college—a western trip now rather than those north-south trips back and forth from school. I had forgotten about Narcissa Whitman, a historic figure I’d last studied in the fourth grade during Pacific Northwest lessons, and I failed to notice that we were a few miles from where she’d lived, where she’d been killed. The purpose of my trip, with my mother and sister in 1979, was to buy a wedding dress. A long drive—125 miles from Moscow, two and a half hours, more switchbacks until we reached the Washington version of the rolling brown-women hills, miles of wheat under a brilliant spring sun. I’m rather surprised to this day that my mother went along with the plan, as there were plenty of dress shops in our town of Boise. But I’d seen a particular dress in a magazine, a gown I was sure I had to wear to my May wedding, with layers of lace, creamy edges, and a train fit for royalty. The dress was available only in this Walla Walla store and I, swept up in the illusions of romance, swept up in doing my part as a young woman of the West, wanted it.

Maybe I had an opportunity to reconsider what I’d committed to during our quiet drive out of Idaho and into Washington, out of one corner of the Palouse and into another. I was 21, scared out of my mind about leaving the cocoon that college had become for me, my nearly perfect grades and lofty conversations (so it felt at the time) with English-major friends about lines of poetry and passages of prose. I was unsteady about leaving the place that had invited me, for the first time, to form ideas of my own, to wonder about my own possibilities. Yet I was incapable of other considerations, finding a job, attending graduate school, traveling to some distant place in the world. I’d been raised to adhere to an unspoken code—so embedded that I’m not sure I have language for it even now—that had to do with loyalty to place and an obligation to certain family mores, including the staunch support of your husband’s fierce independence and little of your own. I opted for what seemed like the easiest and most logical step into adulthood. I’d marry a boy who both awed and troubled me deeply.

If I let some of the panic I’d hidden away about our relationship, his and mine, bubble up in me as we drove to Walla Walla, I don’t remember doing so. I’d convinced myself it was the thing to do, get married, so my mother transported me toward the shop—toward the gown deemed too expensive when we arrived—and my sister (who wed soon after me) and I chose another, more conventional, with less lace and a conservative train, to wear at our respective weddings. The trip was accomplished, the gown purchased, another stone set hard, another detail that made it impossible for me to change my mind. I’ve sometimes allowed myself anger at my mother—why didn’t she say something, why didn’t she point out the obvious disasters ahead with this boy-man whom I’d soon meet at the altar? But of course I wouldn’t have listened to her. Her arguments wouldn’t have mattered. And, besides, this is what young women in Idaho did. They found husbands and raised families. She’d married my father at a ridiculously young age, already pregnant with me. I, too, was pregnant on this wedding-dress-shopping day, though my mother didn’t know it yet. I’d hardly let myself know it. Another unconscious stone set hard, this baby on its way, the most convincing strategy yet to keep me headed toward the only future I would let myself consider.

Last spring, many years divorced from that first husband and our children raised to adulthood, I returned to Waiilatpu, a location I have visited several times now. The day was hot, and I sweated all the way up the steep rise of Memorial Hill at one end of the mission grounds. At the top, I stood next to the marble column erected in tribute to the white people who’d died at the mission on that November day. There still is no memorial there for the Cayuse: nearly half the tribe died from measles brought in the wagon trains that pulled into the Whitman compound; hundreds of others killed in retaliation for the deaths of the missionaries and others at Waiilatpu; five chiefs publicly hanged in Oregon City, men who were made a hideous spectacle and thrown in an unmarked grave.

When I first began reading histories of Narcissa Whitman, I wanted to despise her for the damage she’d done, for the movements, some of them severe, she’d set in motion. Because this young woman had a religious fire in her breast that propelled her to travel thousands of miles to spread her version of the Gospel, people lost their lives and their land, their very way of life. But is it easy to draw that straight line after all? Narcissa’s own intentions, if her journals are to be believed, was to have an effect on a small group of people—not to influence the entire white settlement of the West. The changes writ large were an accidental consequence of her mission. The Whitman Massacre, as it’s known, provided exactly the right excuse at the right time for wiping out a once-mighty tribe and to plant the ground with prosperous white farmers. To plant that ground with acres and endless acres of wheat.

On the afternoon of the attack on Waiilatpu, Narcissa pulled the tomahawk from Marcus’s head and packed his wound with ashes from the fireplace, an act that probably extended his life by some hours. Survivors said that he spoke to her before he died, and that she spoke to him. And then he was gone and she was left alone to manage the dozen and some children and women in the house with her, and to face the mayhem outside—men being hacked or shot from one end of the compound to another, buildings trashed, fires started. Her husband was dead in the living room, her only biological child was buried at the bottom of the hill, her mother and sisters absent from her life for over a decade. She was alone: staring directly into her own demise.

On this last visit of mine, I walked back down the hill and over to the shady section of the grounds, to the communal grave of the 14 people killed at Waiilatpu. In 1897, the bodies were disinterred, reburied with dignity, designated with a marble slab. Narcissa Prentiss Whitman is listed second among the dead, after her husband, on the weather-beaten stone. I stood there for a moment and thought of my own failures, which hold, of course, significantly smaller stakes and consequences—private failures that few others know about, but that, nonetheless, hurt people I love. A young marriage I should not have entered into despite the pressure I felt to do so, the children we brought into the world who are reeling, still, from the sparring and snarl of their parents. My four daughters understand I was a product of my time, my culture—they seem to accept that it was necessary to break out of my conventional marriage if I was to feed the imagination that would save me from a lifetime of dulled bitterness. But was that excuse enough for the unraveling they had to endure?

There at the gravesite at Waiilatpu, I pulled from my bag a scan of the note, the plant, I’d discovered in the book and squatted to the ground—searching out a piece of matching vegetation. Before long, I found a feathery green weed growing in shade. Tansy. The same type of plant rooted in the same place in 1848, perhaps placed in the soil by Marcus or Narcissa as part of a medicinal herb garden for his treatments. I reached over to pluck a leaf from near the grave of Narcissa Whitman. I tucked that leaf in my pocket for the return trip to my room downtown in the Marcus Whitman Hotel, an inn so highly decorated and refined that Marcus would not have known what to do with himself there.

And now the small piece of plant rests between two sheets of parchment paper, dried and flat. My sprig of tansy is pressed in a book that lies here on my table. The volume is a history of a woman, Narcissa Prentiss Whitman, who came west and stirred unprecedented change; an obdurate woman who, I believe, was increasingly conflicted about her decision to leave home forever to deliver a message that native people did not want or need, and who lived in terror that someone might notice the pinch of her disenchantment. A woman who still promises to teach me much about where I came from and who I am.