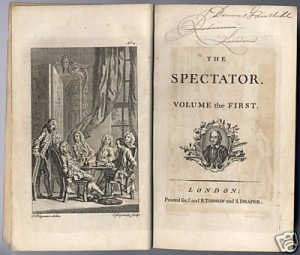

In the first of those casual essays that make up The Spectator, Joseph Addison declares: “I have observed that a reader seldom peruses a book with pleasure until he knows whether the writer of it be a black or a fair man, of a mild or choleric disposition, married or a bachelor, with other particulars of the like nature that conduce very much to the right understanding of an author.”

It’s a famous passage, or, at least, it once was. But is The Spectator still read today? By that I mean is it read for pleasure, by ordinary people, not just by students in 12th-grade English or by undergraduates taking a course in “Prose of the Augustan Age?” I wonder.

John Steinbeck, you may recall, carried a four-volume set of The Spectator on his “travels with Charley.” In his autobiography Benjamin Franklin tells us that he taught himself to write by first studying passages of Addison, then attempting to replicate them in his own words. In this he was, of course, following the celebrated advice of the Great Cham himself, Samuel Johnson: “Whoever wishes to attain an English style, familiar but not coarse, and elegant but not ostentatious, must give his days and nights to the volumes of Addison.”

Back in junior high school, I tried this same exercise with Thoreau, memorizing favorite passages from Walden so that I might infuse my eighth-grade book reports with sentences of oaken sturdiness and Shaker simplicity. Decades later, I discovered that E.B. White—the modern master of the plain style—carried a copy of Walden in his pocket for many years, like a breviary. As kids say, been there, done that.

Though my heart leaps up when I hear the gorgeous music of 17th-century prose (Thomas Browne, Robert Burton, Jeremy Taylor), such organ-concert grandeur is simply beyond me. If only I had a flair for striking similes and metaphors! Alas, nothing ever reminds me of anything else. Equally elusive are the twists and turns of intricately layered, Ciceronian syntax: I have enough trouble holding a thought in my head for more than a couple of lines, let alone carrying it through serpentine clause after clause. I do sometimes console myself by remembering Isaac Babel’s famous dictum: “There is no iron that can pierce the human heart with such stupefying effect as a period placed at just the right moment.”

Because of journalism’s paramount need for clarity and objectivity, working at The Washington Post only reinforced the natural austerity of my prose. An old copy editor I knew used to say, when striking out a needless epithet or intensifier, “No vivid writing, please.” Beauty, I learned, grows out of nouns and verbs, and personal style derives from close attention to diction and sentence rhythm. When Yeats decided that his poems had become too ornamented and flowery, he took to sleeping on a board. Before long, he’d put the Celtic Twilight far behind and was producing such shockingly blunt lines as “Nymphs and satyrs copulate in the foam.”

In my youthful days as a reviewer, I studiously avoided using the first person singular. With some dexterity, one can achieve a sense of intimacy without it, as The New Yorker’s Janet Flanner demonstrated in her wonderful letters from Paris. But the personal essayist needs to master the graceful use of “I.” So … I try.

A writer’s greatest challenge, though, is tone. I like a piece to sound as if it were dashed off in 15 minutes—even when hours might have been spent in contriving just the right degree of airiness and nonchalance. Not that I make it easy on myself to achieve that lightness of touch, given my almost antiquarian penchant for quoting all sorts of authors. See the previous paragraphs for examples.

At all events, let me honor Addison’s injunction: I am neither black nor fair but somewhat in between, my disposition tends toward the ironic and self-deprecatory, and I am married with children (now grown). Other “particulars of the like nature” will emerge over time. Onward!