The Psychologist

Vladimir Nabokov's understanding of human nature anticipated the advances in psychology since his day

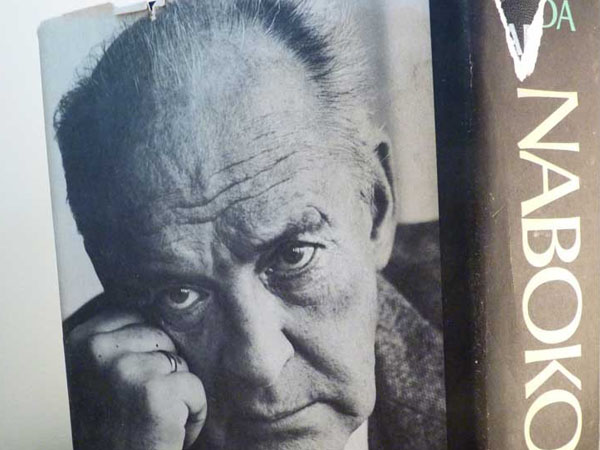

Vladimir Nabokov once dismissed as “preposterous” the French writer Alain Robbe-Grillet’s assertions that his novels eliminated psychology: “The shifts of levels, the interpenetration of successive impressions and so forth belong of course to psychology,” Nabokov said, “—psychology at its best.” Later asked, “Are you a psychological novelist?” Nabokov replied: “All novelists of any worth are psychological novelists.”

Psychology fills vastly wider channels now than when Nabokov, in the mid-20th century, refused to sail the narrow course between the Scylla of behaviorism and the Charybdis of Freud. It deals with what matters to writers, readers, and others: with memory and imagination, emotion and thought, art and our attunement to one another, and it does so in wider time frames and with tighter spatial focus than even Nabokov could imagine. It therefore seems high time to revise or refresh our sense of Nabokov by considering him as a serious (and of course a playful) psychologist, and to see what literature and psychology can now offer each other.

We could move in many directions, which is itself a tribute to Nabokov’s range and strengths as a psychologist: the writer as reader of others and himself, as observer and introspector; as interpreter of the psychology he knew from fiction (Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Proust, Joyce), nonfiction, and professional psychology (William James, Freud, Havelock Ellis); as psychological theorist; and as psychological “experimenter,” running thought experiments on the characters he creates and on the effects he produces in readers. We could consider him in relation to the different branches of psychology, in his own time and now (abnormal, clinical, comparative, cognitive, developmental, evolutionary, individual, personality, positive, social); in relation to different functions of mind, the limits of which he happily tests (attention, perception, emotion, memory, imagination, and pure cognition: knowing, understanding, inferring, discovering, solving, inventing); in relation to different states of consciousness (waking, sleeping, dreaming, delirium, reverie, inspiration, near-death experience, death experience). And we could consider what recent psychology explains in ways that Nabokov foresaw or all but ruled impossible to explain.

He used to tell his students that “the whole history of literary fiction as an evolutionary process may be said to be a gradual probing of deeper and deeper layers of life. … The artist, like the scientist, in the process of evolution of art and science, is always casting around, understanding a little more than his predecessor, penetrating further with a keener and more brilliant eye.” As a young boy he desperately wanted to discover new species of butterflies, and he became no less avid as a writer for new finds in literature, not only in words, details, and images, in structures and tactics, but also in psychology.

He declared that “Next to the right to create, the right to criticize is the richest gift that liberty of thought and speech can offer,” and he himself liked to criticize, utterly undaunted by reputation. He especially liked to correct competitors. He was fascinated by psychological extremes, as his fiction testifies, in for instance the obsession of the suicidal Luzhin in The Defense, the murderous Hermann in Despair, the pedophile Humbert in Lolita, or the paranoid megalomaniac Kinbote in Pale Fire. But he deplored Dostoevsky’s “monotonous dealings with persons suffering from pre-Freudian complexes.” He admired Tolstoy’s psychological insight, and his gift of rendering experience through his characters, but while he availed himself of Tolstoy’s techniques for scenic immersion, he sought to stress also, almost always, the capacity of our minds to transcend the scenes in which we find ourselves. Although Nabokov admired Proust’s ability to move outside the moment, especially in untrammeled recollection, he allotted more space to the constraints of the ongoing scene than Proust did. In The Gift, Nabokov gives Fyodor some of Proust’s frustration with the present, but he also locates the amplitude and fulfillment even here, for those who care to look. And where Proust emphasizes spontaneous, involuntary memory in restoring our links with our past, Nabokov stresses memory as directed by conscious search. He revered Joyce’s verbal accuracy, his precision and nuance, but he also considered that his stream-of-consciousness technique gave “too much verbal body to thoughts.” The medium of thought for Nabokov was not primarily linguistic: “We think not in words but in shadows of words,” he wrote. Thought was for him also multisensory, and at its best, multilevel. As cognitive psychologists would now say, using a computing analogy foreign to Nabokov, consciousness is parallel (indeed, “massively parallel”), rather than serial, and therefore cannot translate readily into the emphatically serial mode that a single channel of purely verbal stream of consciousness can provide.

Famously, Nabokov could not resist deriding Freud. And for good reason: Freud’s ideas were enormously influential, especially in Nabokov’s American years, but his claims were hollow. Nobel laureate Peter Medawar, perhaps the greatest of science essayists, declared in his book Pluto’s Republic, in terms akin to Nabokov’s, that Freudianism was “the most stupendous intellectual confidence trick of the twentieth century.” Nabokov saw the intellectual vacuity of Freudian theory and its pervasiveness in the popular and the professional imagination. He thought it corrupted intellectual standards, infringed on personal freedom, undermined the ethics of personal responsibility, destroyed literary sensitivity, and distorted the real nature of childhood attachment to parents–the last of which has been amply confirmed by modern developmental psychology.

Nabokov treasured critical independence, but he did not merely resist others; he happily imbibed as much psychology as he could from the art of Tolstoy and the science of William James. He was also a brilliant observer not only of the visual and natural worlds but also of the world of human nature, from gesture and posture to outer character and inner self. We can see his acute eye for individuals throughout his letters and memoirs, and in others’ recollections of his sense of them, even many years later, and of course in his fiction.

In one example from the fiction, Ada’s fourth chapter, we see Van Veen on his way from his first school, the elite Riverlane, just after his first sexual experiences, with the young helper at the corner shop, a “fat little wench” who another boy at the school has found can be had for “a Russian green dollar.” The first time, Van spills “on the welcome mat what she would gladly have helped him take indoors.” But “at the next mating party” he “really beg[a]n to enjoy her … soft sweet grip and hearty joggle,” and by the end of term he has enjoyed “forty convulsions” with her. The chapter ends with Van leaving to spend the summer at Ardis, with his “aunt” Marina:

In an elegant first-class compartment, with one’s gloved hand in the velvet side-loop, one feels very much a man of the world as one surveys the capable landscape capably skimming by. And every now and then the passenger’s roving eyes paused for a moment as he listened inwardly to a nether itch, which he supposed to be (correctly, thank Log) only a minor irritation of the epithelium.

Nabokov writes fiction, not psychology, but this typically exceptional passage, a mere 67 words, depends on, depicts, and appeals to psychology. These words and psychology have much to offer each other.

In a sudden switch, Van and Nabokov (VN) contrast the tawdriness of the “fat wench” possessed “among crates and sacks at the back of the shop” with the opulence of the train and Van’s fine apparel. The “elegant first-class apartment” and the “gloved hand” make the most of a cognitive bias, the contrast effect: our minds respond to things much more emphatically in the presence of a contrast, especially a sudden one.

“One feels very much a man of the world,” the passage continues. We can all recall and imagine sudden moments of self-satisfaction, especially at points where life clambers up a level in childhood and adolescence. Recent evolutionary biology has focused on life history theory, species-typical patterns of development and their consequences across species. (Although before life history theory showed our human life patterns in a comparative light, we knew the importance of, and the unique delay in, the onset of human sexual activity.) Psychology long neglected emotion. Now it explores even the social emotions, like those associated with status, which boost levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin in the brain. After puberty, this rise in serotonin increases the inclination to sexual activity—for example in Van, who wakes up at Ardis early the next morning to a “savage sense of opportune license” when, in his skimpy bathrobe, he encounters the 19-year-old servant Blanche.

[adblock-left-01]

In “one’s gloved hand … one feels very much a man of the world,” Van invites us to a common human emotion through the generalizing pronoun “one.” We take this appeal to shared experience for granted. Recognizing shared experience, and wanting to, are at the basis of fiction, and the social life fiction feeds on. But psychology should do more than just take these facts for granted: it should help us explain them.

Mirror neurons, discovered in the 1990s, fire in the same part of the motor area of my brain activated both when I grasp something and when I merely see someone else grasping. This unforeseen component of neural architecture, especially elaborate in humans, helps us to understand and learn from others, and perhaps to cooperate or compete with them. We also have from infancy a far stronger motivation to share experience than do other animals, even chimpanzees: think of an infant’s compulsion to point out things of interest. This heightened motivation to share experience seems to lay the foundation for what has been called human ultrasociality.

We understand the actions of others when we see them by partially reactivating our own experience of such actions, stored in our memories. But more than that, we also attune ourselves to others’ actions and empathize with them, unless we perceive them as somehow opposed to us. Over the past 15 years, psychology has begun to study the remarkably swift and precise ways we attune ourselves rapidly, and often unconsciously, to what we see in others. Van-and-VN appeal here to our shared experience, to our recollection of our pride in reaching a new stage in life, like learning to walk, starting school, or mastering the rudiments of sex.

Recent neuroscience research in grounded cognition shows that thought is not primarily linguistic, as many had supposed, but multimodal, partially reactivating relevant multimodal experiences in our past, involving multiple senses, emotions, and associations. Just as seeing someone grasp something activates mirror neurons, even hearing the word grasp activates the appropriate area of the motor cortex. Our brains encode multimodal memories of objects and actions, and these are partially reactivated as percepts or concepts come into consciousness.

Nabokov rightly stressed that imagination is rooted in memory; that was the very point of entitling his autobiography Speak, Memory. Since the early 1930s it has been known that we store episodic memories, memories of our experiences, as gist, as reduced summaries of the core sense or feel of situations, rather than all their surface details. Our stored knowledge of past situations and stimuli allows us later to, as it were, unzip the compressed file of a memory and to reconstruct an image of the original. Recent evidence shows that memory’s compression into gist evolved not only to save space on our mental hard drives but also to make it easier to activate relevant memories and recombine them with present perception or the imagination of future or other states not experienced. If memories were stored in detail and the details had to match exactly, mental search would be slow and rarely successful. But once memories have been compressed into gist, many memories can be appropriate enough to a new situation or a new imaginative moment to be partially reactivated, according to their common mental keywords or search terms.

Minds evolved to deal with immediate experience. And although human minds can now specialize in abstract thought or free-roaming imagination, we still respond most vividly and multimodally to immediate experience. For that reason more of our multimodal memories can be activated by language that prompts us to recreate experience, as fiction does, rather than more abstract, less personal, less sequential texts. Nabokov was right to insist on the power of the specific in art to stimulate the imagination. In the passage I’ve cited, he and Van appeal to the groundedness of cognition through their use of details like the velvet side-loop and the gloved hand to activate our multimodal memories of their look and feel.

So far I have stressed how these first few words appeal to experience we share, but the passage also implies different kinds of distance. There’s the distance between Van as adult narrator–as by this stage we already know him to be, despite his third-person presentation of young Van as a character–and Van as a 14-year-old feeling himself “very much a man of the world.” The word “one,” which generalizes from his situation, as if adolescent Van can now grandly sum up a new truth he has reached from his lofty vantage point of experience, can only seem absurd to Van many years later, after much more sexual exploration than a few furtive convulsions with a shopgirl. As narrator, he can see a 14-year-old’s pride in his experience as proof of his past self’s relative innocence. But that distance between Van as character and Van as narrator also sets up something for us to share with the latter: we have all reflected ironically later in life upon satisfactions that had seemed robust when we first felt them. We see here how memory compression into gist may help us retrieve a whiff of similar episodes we have experienced or witnessed.

But apart from this multiple appeal to what we share, Van and especially Nabokov behind him also know that the way Van’s recollection is worded will also establish a different kind of distance between Van and the reader. Many readers never travel first class, and few males, however “elegant,” now wear gloves on a summer’s day. Van has a strong element of dandified class-consciousness mingling with his pride at being “very much a man of the world.” The generalizing pronoun “one,” which on one level invites readers to share a common experience, on another level also discloses Van’s intellectual pride in arriving at the new generalization, and his foppish indulgence in his sense of superiority to others. The upper-class English use of “one,” applied to oneself, seen as a mark of high-toned speech, reinforces the snobbery that amplifies Van’s self-satisfaction, and complicates the appeal to our identification with him–although we too will recognize moments when we have felt superior to others.

Let’s move one more clause into the passage: “one feels very much a man of the world as one surveys the capable landscape capably skimming by.” Here Van-and-VN comically evoke our human tendency to see the world through the tinted lenses of our emotions, or even to project our emotions onto what we perceive. “Capable” applies legitimately only to entities that can act; Van-and-VN absurdly apply it to the landscape, and then, adverbially, to the way the landscape skims past Van’s train window. Narrator and author know the comedy of twice misapplying this term, which suits only Van’s sense of himself. Nabokov suddenly confronts us in this surprising, vivid, ironic, amusing way with an instance of our human tendency to project our emotions onto our world. Psychologists study this kind of projection through “priming,” what we notice or think of first if we have been exposed to, or primed with, say, positive or negative images. Yet despite the comedy of Van’s emotional priming, Nabokov and Van also appeal to our imaginations through our memories, in that landscape “skimming by.”

In the next, and final, sentence, “And every now and then the passenger’s roving eyes paused for a moment as he listened inwardly to a nether itch,” Van-and-VN activate our own multimodal memories and awareness. They tap both into our proprioceptive sense (our awareness, from inside, of our body positions and sensations) of the ways that our eyes move as we attend to an inner discomfort or pain and into our memories of others glancing sideways in thought or hurt. The surprise and yet the naturalness of the metaphor, “listened to a nether itch,” trigger another multimodal activation (roving eyes, inner ears, touch) of multimodal memories of monitoring our inner sensations.

[adblock-right-01]

But Van, attending to this nether itch, supposed it “to be (correctly, thank Log) only a minor irritation of the epithelium.” We are invited to infer that Van has a few momentary worries about a venereal disease he could have contracted from the “fubsy pig-pink whorelet” at the shop near his school, and that sometime later, when the itch does not recur, he confirms to himself that it had been no cause for real alarm. Nabokov stresses the importance in the development of modern fiction of writers’ learning to trust readers’ powers of inference, because we prefer to imagine actively, to see in our mind’s eye much more than what the page spells out explicitly. We intuit Van’s concern through our familiarity with his context. Because we now share that common ground with him, things don’t have to be spelled out in order for us to infer the whole situation, and that successful inference further confirms our sense of the ground we share with Van.

Van’s unfounded fears of venereal disease may add another note of comedy, but they also prepare us structurally both for the romance of love and sex with Ada at Ardis, where Van’s train will take him, a romance highlighted by contrast with the schoolboy lineup for paid sex, and for the tragic aspects of Ardis as sexual paradise, not least in the venereal disease that, through Blanche, enfolds itself into the romantic myth of Van and Ada there.

This brief paragraph, immediately accessible, immediately evocative of multiple sensations, emotions and memories, typically embodies a multiple awareness: of Van at 14 on the train; of him a little later that summer, when he can feel sure he has not caught a venereal disease; of him as a much older narrator recalling his young self and inviting his readers to sense what we share with him, but also to recognize young Van’s cocky sense of what makes him privileged and apart. As narrator, Van evokes and reactivates the experience, yet he also sees himself from outside: “And every now and then the passenger’s roving eyes paused.” Psychologists distinguish between a field and an observer relationship to an experience or a memory: an inner view, as if amid the field of experience, and an outer view, observing oneself as if from the outside. Ordinarily we experience life in the “field” condition; but precisely because we can compress memories into gist, we can also afterward recall our experience as if from the outside, as in the radical recombinations of our memories in our dreams. As we read, we also tend to toggle or glide between imagining ourselves within the experience of a focal character (Van seeing the landscape swimming by, or listening to his nether itch)and an outer view—(seeing Van with gloved hand in the velvet side-loop).

Think how different our experience of reading Nabokov is from our experience as readers of Tolstoy. In Tolstoy we seem to enter immediately into the minds and experience of the focal characters, because he conjures up all the relevant elements of the situation, the physical presence, the personalities of those involved, the interactions between them, and the relevant information about their past relations. Our imaginations seem contained entirely within the scene; we feel ourselves within the space the characters occupy. But Nabokov prefers to evoke and exercise our recognition of the manifold awareness of consciousness: the different Vans here, character now, character slightly later, narrator much later, felt from inside or seen from outside; the different appeals to recognize what we share and what holds us at a distance from Van; the awareness on rereading of the appeal to first-time readers and to our accumulated knowledge of the rest of the book. Tolstoy also builds up scenes gradually, coordinating characters’ actions and perceptions. Nabokov speeds us into his railroad scene without warning, without explicitness (only “first-class compartment,” “skimming,” and “passenger” specify the situation), without lingering (the scene ends here), and without spelling out the when or where until we infer them at the beginning of the next chapter. He has confidence in our pleasure in imagination, inference, and orientation.

Clinical, comparative, developmental, evolutionary, and social psychology in the past 30 years have devoted a great deal of attention to theory of mind and to metarepresentation. Theory of mind is our capacity to understand other minds, or our own, in terms of desires, intentions, and beliefs. Metarepresentation is our capacity to understand representations (pictures, reports, perceptions, memories, attitudes, and so on) as representations, including the representations other minds may have of a scene. Although some intelligent social animals appear to understand others of their kind in terms of desires and intentions, only humans have a clear understanding of others in terms also of what others believe, and they factor beliefs effortlessly into the ways in which they draw inferences. By adolescence, we can readily understand four degrees of intentionality: A’s thoughts about B’s thoughts about C’s thoughts about D’s. As adults, we start to make errors with, but we can still manage, five or six degrees: our thoughts as rereaders, say, about our thoughts as first-time readers about Nabokov’s thoughts about Van the narrator’s thoughts about Van’s thoughts at Ardis about Van’s thoughts on the train to Ardis.

Nabokov values the multilevel awareness of the mind and works to develop it in himself and in his readers and rereaders, as he discusses most explicitly through his character Fyodor in The Gift. Fyodor deliberately sets himself exercises of observing, transforming, recollecting, and imagining through the eyes of others. Frustrated at earning his keep by foreign language instruction, he thinks: “What he should be really teaching was the mysterious thing which he alone–out of ten thousand, a hundred thousand, perhaps even a million men–knew how to teach: for example–multilevel thinking,” which he then defines. The very idea of training the brain in this way, as Fyodor does for himself, as he imagines teaching others to do, as he learns to do for his readers, as Nabokov learned over many years to do for his readers, fits with neuroscience’s recent understanding of brain plasticity, the degree to which the brain can be retrained, fine-tuned, redeployed.

Play has been nature’s main way of making the most of brain plasticity. It fine-tunes animals in vital behaviors like flight and fight, hence the evolved pleasure animals take in chasing and frisking and in rough-and-tumble fighting, nature’s way of ensuring they’ll engage in this training again and again. In my book On the Origin of Stories I look at art as a development of play, and as a way of fine-tuning minds in particular cognitive modes that matter to us: in the case of fiction, our expertise in social cognition, in theory of mind, in perspective taking, in holding multiple perspectives in mind at once. As I made that case, I was not thinking of Nabokov, but he takes this kind of training of the mind–perception, cognition, emotion, memory, and imagination–more seriously, and more playfully, than any other writer I know.

I have used one brief and superficially straightforward example from Ada to show how much psychological work we naturally do when we read fiction, and especially when we read Nabokov’s fiction, and how much light psychology can now throw on what we do naturally when we read fiction. Literature’s aims differ considerably from those of research psychology. Nevertheless literature draws on human intuitive psychology (itself also a subject in recent psychology) and exercises our psychological capacities. Literature aims to understand human minds only to the degree it seeks to move human minds. It may move readers’ minds, in part, by showing with new accuracy or vividness, or at least with fresh particulars, how fictional minds move, and by showing in new ways how freely readers’ minds can move, given the right prompts. Psychology also wants to understand minds, both simply for the satisfaction of knowing and also to make the most of them, to limit mental damage or to extend mental benefits. It uses the experimental method. We can also see fictions as thought experiments, experiments about how characters feel, think, and behave, and about how readers feel, think, and behave, and how they can learn to think more imaginatively, feel more sympathetically, act more sensitively. Fictions are experiments whose results will not be systematically collected and peer reviewed–and then perhaps read by a few psychologists–but might well be felt vividly by a wide range of readers.

Nabokov thinks that at their best, art and science meet on a high ridge. Psychology, after wandering along wrong paths to Freud or behaviorism, has just emerged onto the ridge. Nabokov may have doubted psychology could crest this particular ridge, but I think he has met science there.