Few things in nature remind you of the transience of human life so vividly as moss. Compared to these ancient and primitive nonflowering plants—which first evolved on land at least 470 million years ago—human existence is like ‘a passing shadow, a fading cloud, a fleeting breeze.’

Although they may seem soft and tufty, moss plants are so tough that they can survive freezing for as many as 1,530 years. Last year, researchers led by Catherine La Farge at the University of Alberta in Edmonton revived moss plants entombed in ice during the Little Ice Age (1550-1850 AD) on Ellesmere Island, in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The blackened plants had been exposed to the air again after the rapid retreat of a glacier in response to the warming climate. This year, British Antarctic Survey researchers reported that they had regrown moss trapped in Antarctic ice for a millennium and a half.

Now researchers led by Ralf Reski, professor of plant biotechnology at the University of Freiburg in Germany, have discovered why: mosses owe their extraordinary resilience to cold to an array of genes—some unique to mosses—that turn on as the temperature drops.

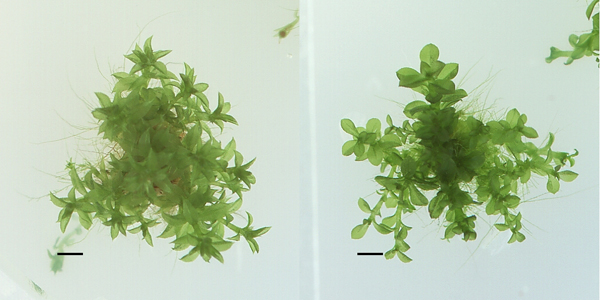

Reski and his colleagues analyzed the genome of a moss called Physcomitrella patens, which he had earlier developed as a model system that is now studied by researchers worldwide. The team exposed four-week-old P. patens moss plants to a temperature of 3.5 degrees Celsius for between one hour and 24 hours, and discovered that the expression of 3,220 genes—some 11 percent of the moss plant’s total—was “significantly affected” as the temperature dropped. Some of the genes, the team found, code for abscisic acid, or ABA, a stress hormone that in higher plants causes leaves to fall in autumn. Rising levels of ABA trigger a second wave of activity among genes that code for cold-protective proteins and sugars.

Reski’s research, he wrote to me via email, indicates that “mosses are generally more resilient to environmental changes than the more specialized higher plants” and they may therefore survive a changing climate more efficiently than other plant groups. The findings also suggest that mosses deserve more respect than they now get. “Mosses ‘saw’ the dinosaurs coming and going, they ‘saw’ us coming. And if we are not careful with our planet they will ‘see’ us going. But they will survive,” Reski says. And besides, he adds lovingly, “mosses are very beautiful tiny creatures.”