What Columbus Day Really Means

If you think the holiday pits Native Americans against Italian Americans, consider the history behind its origin

During the run-up to Columbus Day I usually get a call from at least one and sometimes several newspaper reporters who are looking for the latest on what has become one of the most controversial of our national holidays. Rather than begin with whatever issues the media are covering—topics like the number of deaths in the New World caused by the European discovery; or the attitude of Columbus toward the indigenous inhabitants of the Caribbean (whom he really did want to use as forced laborers); or whether syphilis really came from the Americas to Europe; or whether certain people (the cast of The Sopranos, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia) deserve to be excluded from or honored in the parade in New York—I always try to remind the reporters that Columbus Day is just a holiday.

Leave the parades aside. The most evident way in which holidays are celebrated is by taking a day off from work or school. Our system of holidays, which developed gradually over time and continues to evolve, is founded upon the recognition that weekends are not sufficient, that some jobs don’t offer much time off, and that children and teachers need a break now and then in the course of the school year. One characteristic of holidays is that unless they are observed widely, which is to say by almost everyone, many of us wouldn’t take them. There are so many incremental reasons for not taking time off (to make some extra money, to impress the boss, or because we’re our own bosses and can’t stop ourselves) that a lot of us would willingly do without a day’s vacation that would have been good both for us and for society at large if we had taken it. That is why there are legal holidays.

But which days should be holidays? Another way of posing the question would be to say, “Given that holidays are necessary, but that left to their own devices people would simply work, how do you justify a legal holiday so that it does not appear completely arbitrary, and so that people will be encouraged to observe it?” Most of the media noise around the Columbus Day holiday is about the holiday’s excuse, not the holiday itself. Realizing that helps to put matters in perspective.

In a country of diverse religious faiths and national origins like the United States, it made sense to develop a holiday system that was not entirely tied to a religious calendar. (Christmas survives here, of course, but in law it’s a secular holiday much like New Year’s Day.) So Americans do not all leave for the shore on August 15th, the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin, the way Italians do; and while St. Patrick’s Day is celebrated by many Americans, it is not a legal holiday in any of the states. The American system of holidays was constructed mostly around a series of great events and persons in our nation’s history. The aim was to instill a feeling of civic pride. Holidays were chosen as occasions to bring everyone together, not for excluding certain people. They were supposed to be about the recognition of our society’s common struggles and achievements. Civic religion is often used to describe the principle behind America’s calendar of public holidays.

Consider the range and variability of the meanings of our holidays. Certainly they have not always been occasions for celebration: Memorial Day and Veterans’ Day involve mourning for the dead and wounded. Labor Day commemorated significant hardships in the decades when unions were struggling to organize. Having grown up in the 1960s I remember how Abraham Lincoln’s Birthday (now lumped in with Presidents’ Day, and with some of its significance transferred to Martin Luther King, Jr. Day) took on special meaning during the Civil Rights movement and after the JFK assassination.

[adblock-right-01]

When thinking about the Columbus Day holiday it helps to remember the good intentions of the people who put together the first parade in New York. Columbus Day was first proclaimed a national holiday by President Benjamin Harrison in 1892, 400 years after Columbus’s first voyage. The idea, lost on present-day critics of the holiday, was that this would be a national holiday that would be special for recognizing both Native Americans, who were here before Columbus, and the many immigrants—including Italians—who were just then coming to this country in astounding numbers. It was to be a national holiday that was not about the Founding Fathers or the Civil War, but about the rest of American history. Like the Columbian Exposition dedicated in Chicago that year and opened in 1893, it was to be about our land and all its people. Harrison especially designated the schools as centers of the Columbus celebration because universal public schooling, which had only recently taken hold, was seen as essential to a democracy that was seriously aiming to include everyone and not just preserve a governing elite.

You won’t find it in the public literature surrounding the first Columbus Day in 1892, but in the background lay two recent tragedies, one involving Native Americans, the other involving Italian Americans. The first tragedy was the massacre by U.S. troops of between 146 and 200 Lakota Sioux, including men, women and children, at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, on December 29, 1890. Shooting began after a misunderstanding involving an elderly, deaf Sioux warrior who hadn’t heard and therefore did not understand that he was supposed to hand over his rifle to the U.S. Cavalry. The massacre at Wounded Knee marked the definitive end of Indian resistance in the Great Plains. The episode was immediately seen by the government as potentially troubling, although there was much popular sentiment against the Sioux. An inquiry was held, the soldiers were absolved, and some were awarded medals that Native Americans to this day are seeking to have rescinded.

A second tragedy in the immediate background of the 1892 Columbus celebration took place in New Orleans. There, on March 14, 1891—only 10 weeks after the Wounded Knee Massacre—11 Italians were lynched in prison by a mob led by prominent Louisiana politicians. A trial for the murder of the New Orleans police chief had ended in mistrials for three of the Italians and the acquittal of the others who were brought to trial. Unhappy with the verdict and spurred on by fear of the “Mafia” (a word that had only recently entered American usage), civic leaders organized an assault on the prison to put the Italians to death. This episode was also troubling to the U.S. Government. These were legally innocent men who had been killed. But Italians were not very popular, and even Theodore Roosevelt was quoted as saying that he thought the New Orleans Italians “got what they deserved.” A grand jury was summoned, but no one was charged with a crime. President Harrison, who would proclaim the Columbus holiday the following year, was genuinely saddened by the case, and over the objections of some members of congress he paid reparations to the Italian government for the deaths of its citizens.

Whenever I hear of protests about the Columbus Day holiday—protests that tend to pit Native Americans against Italian Americans, I remember these tragedies that occurred so soon before the first Columbus Day holiday, and I shake my head. President Harrison did not allude to either of these sad episodes in his proclamation of the holiday, but the idea for the holiday involved a vision of an America that would get beyond the prejudice that had led to these deaths. Columbus Day was supposed to recognize the greatness of all of America’s people, but especially Italians and Native Americans.

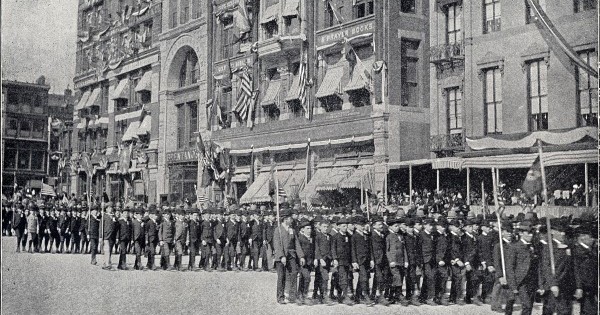

Consider how the first Columbus Day parade in New York was described in the newspapers. It consisted mostly of about 12,000 public school students grouped into 20 regiments, each commanded by a principal. The boys marched in school uniforms or their Sunday best, while the girls, dressed in red, white and blue, sat in bleachers. Alongside the public schoolers there were military drill squads and 29 marching bands, each of 30 to 50 instruments. After the public schools, there followed 5,500 students from the Catholic schools. Then there were students from the private schools wearing school uniforms. These included the Hebrew Orphan Asylum, the Barnard School Military Corps, and the Italian and American Colonial School. The Dante Alighieri Italian College of Astoria was dressed entirely in sailor outfits. These were followed by the Native American marching band from the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, which, according to one description, included “300 marching Indian boys and 50 tall Indian girls.” That the Native Americans came right after the students from the Dante Alighieri School speaks volumes about the spirit of the original Columbus Day.

[adblock-left-01]

I teach college kids, and since they tend to be more skeptical about Columbus Day than younger students, it’s nice to point out that the first Columbus Day parade had a “college division.” Thus 800 New York University students played kazoos and wore mortarboards. In between songs they chanted “Who are we? Who are we? New York Universitee!” The College of Physicians and Surgeons wore Skeletons on their hats. And the Columbia College students marched in white hats and white sweaters, with a message on top of their hats that spelled out “We are the People.”

So Columbus Day is for all Americans. It marks the first encounter that brought together the original Americans and the future ones. A lot of suffering followed, and a lot of achievement too. That a special role has been reserved for Italians in keeping the parades and the commemoration alive for well over a century seems right, since Columbus was Italian—although even in the 1890s his nationality was being contested. Some people, who include respectable scholars, still argue, based on elements of his biography and family history, that Columbus must really have been Spanish, Portuguese, Jewish, or Greek, instead of, or in addition to, Italian. One lonely scholar in the 1930s even wrote that Columbus, because of a square jaw and dirty blond hair in an old portrait, must have been Danish. The consensus, however, is that he was an Italian from outside of Genoa.

So much for his ethnicity. What about his moral standing? In the late 19th century an international movement, led by a French priest, sought to have Columbus canonized for bringing Christianity to the New World. To the Catholic Church’s credit, this never got very far. It sometimes gets overlooked in current discussions that we neither commemorate Columbus’s birthday (as was the practice for Presidents Washington and Lincoln, and as we now do with Martin Luther King, Jr.) nor his death date (which is when Christian saints are memorialized), but rather the date of his arrival in the New World. The historical truth about Columbus—the short version suitable for reporters who are pressed for time—is that Columbus was Italian, but he was no saint.

The holiday marks the event, not the person. What Columbus gets criticized for nowadays are attitudes that were typical of the European sailing captains and merchants who plied the Mediterranean and the Atlantic in the 15th century. Within that group he was unquestionably a man of daring and unusual ambition. But what really mattered was his landing on San Salvador, which was a momentous, world-changing occasion such as has rarely happened in human history. Sounds to me like a pretty good excuse for taking a day off from work.