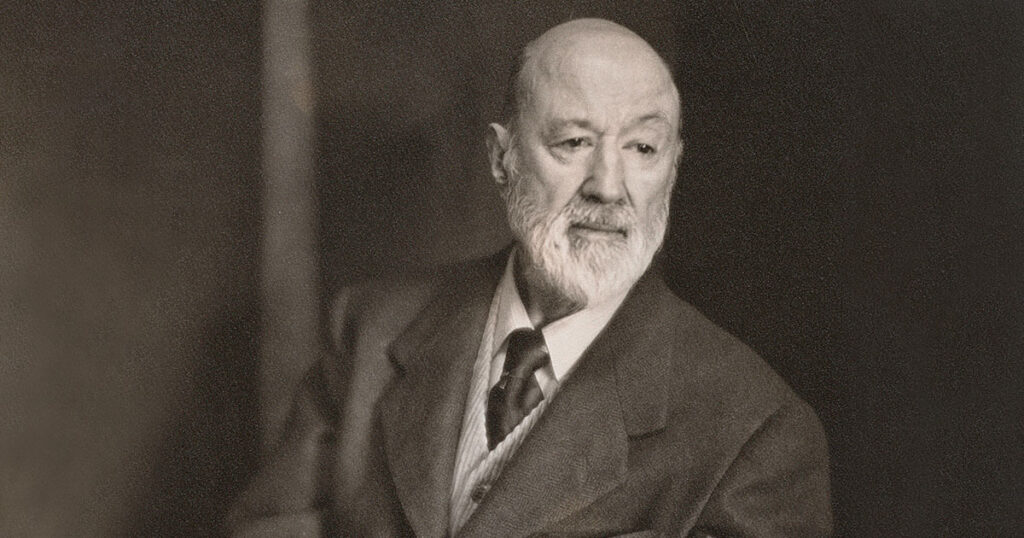

Listen to just about anything Charles Ives wrote—his symphonies, his songs, his string quartets, his monumental, fiendishly difficult Concord Piano Sonata—and you may experience a range of simultaneous emotions: awe, nostalgia, exhilaration, but also perhaps bewilderment. Ives remains, in his 150th anniversary year, too little known, often misunderstood, woefully underperformed. The time for reassessment is now.

In our Autumn issue, Joseph Horowitz—who has long championed Ives’s music, both as a cultural historian and as a concert producer—makes the connection between Ives and Gustav Mahler, two composers who drew from the past to root themselves in an unstable present. Here we continue our Ives exploration with three additional essays. In “The Power of the Common Soul,” the distinguished musicologist J. Peter Burkholder delves into Ives’s scores and finds a pervasive feeling of hope, one that is eminently necessary in our fraught times. In “The Sound of the Picturesque,” Tim Barringer, one of our leading authorities on 19th-century American art, considers how deeply Ives was influenced by the visual. And in “Battle Hymns,” Allen C. Guelzo brings his considerable expertise on Abraham Lincoln and 19th-century America to bear on Ives’s connections to the Civil War. Read this package of essays, and you’ll see how wide a swath Ives cuts across American arts and letters, from the Civil War and its prolonged aftermath through the first half of the 20th century.

This year, with a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, Horowitz and Burkholder are co-curating a major festival—“Charles Ives at 150: Music, Imagination and American Culture”—to be held at Indiana University’s Jacobs School of Music from September 30 to October 8. Several leading artists will take part, including the pianists Jeremy Denk, Gilbert Kalish, and Steven Mayer; the Pacifica Quartet; the baritone William Sharp; and the violinist Stefan Jackiw. Nearly every important Ives piece will be performed: the Second and Third Symphonies; the piano sonatas, violin sonatas, and string quartets; a wide range of songs; and the symphonic poems Three Places in New England, The Unanswered Question, and Central Park in the Dark. The performances will be multidisciplinary, with extensive commentary providing context and background and illustrating Ives’s central contributions to the narrative of American culture. The performance of the Three Places in New England, moreover, will feature a visual presentation created by Peter Bogdanoff, who uses audio, video, and computer-based media to present the arts to new audiences. There will also be master classes, talks, colloquia, and panel discussions.

The festival in Bloomington is the largest of this year’s Ives sesquicentennial events, but it isn’t the only one. In July, the Brevard Music Festival in North Carolina held a week’s worth of concerts and classes, and forthcoming celebrations will take place at Bard College (“The Orchestra Now,” November 9–21) and in Chicago and Normal, Illinois, featuring the Chicago Sinfonietta in collaboration with Illinois State University (February 17–22, 2025). All four Ives festivals are supported by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, and a list of program highlights can be found here.

Why are these commemorations so vitally important? And what makes Ives such an original? Earlier American composers such as John Knowles Paine, George Whitefield Chadwick, and Edward MacDowell looked largely to the Germanic symphonic tradition for idioms to adapt and emulate. Ives, meanwhile, drew from his Danbury, Connecticut, boyhood. He recalled the sounds of brass bands, church choirs, crowds cheering loudly on a village green, a church bell tolling in the distance, haunting echoes of a specific New England time and place that he manipulated in harmonically and rhythmically complex ways. It was as inventive a mix of the vernacular and the modern as any composer had dared imagine. And yet, for most of his life, Ives lacked the recognition he deserved. Perhaps it didn’t help that despite first-class professional training as an organist and a composer, he chose as his profession not music but the life-insurance business.

When Leonard Bernstein evangelized on behalf of Ives’s Second Symphony in the 1950s, it may have seemed as if the composer’s time had finally come. More recently, Michael Tilson Thomas and other musicians have taken up the cause, but Ives’s pieces have never really enjoyed a sustained presence on the concert stage. In his sesquicentennial year, we will have a chance to encounter his music anew, to understand his contributions to the American experience, to see him not as some isolated genius but as the rightful heir to the Transcendentalists, Melville, and Twain—to understand why so many believe him to be the supreme creative genius in American classical music.

Charles Ives at 150

- “Anchoring Shards of Memory” by Joseph Horowitz

- “The Power of the Common Soul” by J. Peter Burkholder

- “The Sound of the Picturesque” by Tim Barringer

- “Battle Hymns” by Allen C. Guelzo