When Kerouac Met Kesey

The two counterculture heroes, one representing the Beat ’50s and one the psychedelic ’60s, had a lot less in common than you might expect

If the 1950s and ’60s belonged to Jack Kerouac, then the ’60s and ’70s belonged to Ken Kesey. Both of them were my clients, and I liked and admired each of them. Although they differed in age, personality, and writing styles, they overlapped as writers of their times, and there was room for both. Each man was an iconoclastic thinker whose writing and philosophy inspired passionate devotion in his readers.

Before I ever met Kesey, Tom Guinzburg, president of Viking Press, called me one day in 1961 to ask whether Kerouac would write a blurb for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Kesey’s first novel. Tom had bought the book, but Viking had not yet published it. Publishers are always looking for well-known writers to offer positive comments for the book jacket or a press release. A blurb can be particularly helpful if readers feel there is a creative relationship between the two writers. I had no idea whether Kerouac would help, because I couldn’t remember his having blurbed before, but I didn’t think he would be offended if I asked. I thought he might even be flattered. So I told Tom to send me the manuscript. I read it before passing it on to Jack, and I knew right then that I wanted to work with Kesey. His novel was a bold, creative story of what happens in a mental institution—a very daring subject for his time. In the end, Jack did not write a blurb; he felt uncomfortable doing it, perhaps not wanting to get into that arena and all that went with it,and I respected that.

I called Guinzburg to tell him I’d like to represent Kesey, who didn’t have an agent, and then got in touch with Ken. He was delighted, and we started working together. In 1963, Ken sent me his second novel, Sometimes a Great Notion, and soon came to New York for the Broadway opening of the play based on Cuckoo’s Nest, starring Kirk Douglas as McMurphy and Joan Tetzel as Nurse Ratched.

When I met him then, Ken shook my hand with a firm grip. He was 28 and had the piercing blue eyes and warm smile of Paul Newman—but with not as much hair. (Newman would play the lead in the film adaptation of Sometimes a Great Notion.) He was five feet 10 and trim, and he had bushy sideburns that were his signature and wore a woolen bill cap. He seemed to be enjoying everything he did.

Kesey had brought his family and friends with him to Manhattan, and I soon realized that despite his many interests and his peripatetic life, family was a major part of who he was. The night before the play opened, we were sitting around in my apartment on Central Park West, which had a great view of the skyline looking south toward the Empire State Building. But the Kesey contingent, after a day visiting the Museum of Natural History and the site of the upcoming World’s Fair at Flushing Meadows in Queens, ignored the view. They were totally absorbed with one another.

I had just finished reading the manuscript of Sometimes a Great Notion and was impressed and moved. I had never been to Oregon, but Kesey’s writing gave me a vivid picture of that part of the country.

“Ken,” I said, “I think you’ve written a novel that will become an American classic!”

“Thanks very much,” he said immediately, “but I don’t think you’re right. The story is too complicated.”

He turned out to be more right than I was. When I read it again, I realized that although the story bears all the markings of an epic American tragedy, the rotating first-person narrative (often blurring one character’s perspective with that of the next) detracted from the premise of the Great American Novel: no single character or situation serves as emblematic of the novel’s period, and there is no clear hero or villain. But the distinctions it explores between the East Coast and the West Coast, nature and civilization, rugged individualism and communitarianism, all seem very much in keeping with the spirit of the times.

Opening night for Cuckoo’s Nest, at the Cort Theatre on November 13, 1963, was memorable. The house was packed, and Dale Wasserman’s dramatization was superb. But the subject of a mental institution was not yet acceptable to all the theatergoers. Although it was a riveting performance, by the end of Act I about 15 to 20 percent of the audience had walked out. Those of us who remained were spellbound.

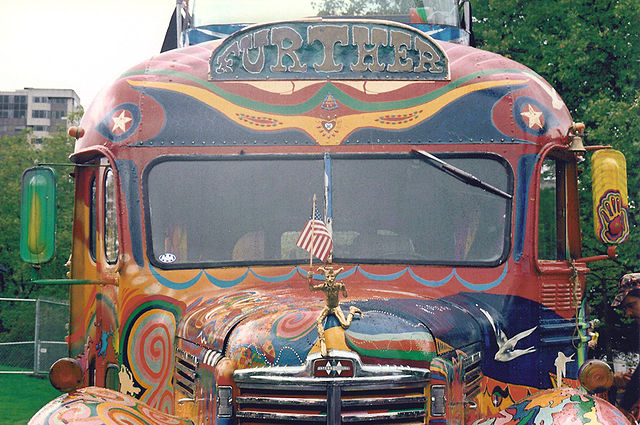

During his trip back to Oregon in 1963, Ken and his entourage began to think about what would become the Merry Pranksters’ bus trip to New York the following year to see the World’s Fair. The ’60s was rapidly becoming Kesey’s decade, especially once Further, the psychedelically painted 1939 International Harvester school bus bearing the Merry Pranksters, arrived in New York City in 1964. The Pranksters were a varied, fun-loving group of about 16 to 20 men and women, including Kesey, his family and friends, and their friends. Neal Cassady, the wiry, muscular inspiration for Dean Moriarty in Kerouac’s On the Road, drove the bus across the country.

[adblock-left-01]

Tom Wolfe would immortalize the Merry Pranksters in his 1968 book The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, which sold many more copies than either of Kesey’s novels had at that time. As a result, Kesey the man would become more of a legend than Kesey the writer.

All the Pranksters had nicknames for the trip relating to what they wore (or didn’t) or to things they did. Kesey wore a red, white, and blue bandana around his head, so he was Captain Flag. Ken’s wife, Faye Kesey, became Betsy Flag. Others were named the Intrepid Traveler, Hardly Visible, Camera Man, Stark Naked, Gretchen Fetchen, Zonker, Hassler, Highly Charged, Dismount, Generally Famished (Jane Burton, a Stanford philosophy major who was always hungry), Sometimes Missing, and Brother Charlie (Ken’s brother Chuck, who ran the family cooperative creamery).

When the bus reached what they all referred to as “Madhattan,” Kesey phoned me right away.

“How was it?” I asked, not knowing what to expect.

In a classic Kesey response, he said, “Sterling, when we hit Manhattan, the city just rolled over on its back and purred.”

I had never met Neal Cassady before Further arrived in the city, and I wouldn’t say I got to know him well: he didn’t tend to sit still on a trip like that one. I was told he shaved every morning with a dry razor, which seemed somehow appropriate. He had done two years in San Quentin on a minor drug charge, and in 1962 he showed up at Perry Lane, Kesey’s hangout near Stanford, where they became friends. One Prankster told me Cassady was an “all-time great talker who could go on for hours nonstop without repeating himself” and without talking nonsense, and that “he had a brilliant mind and could recite whole paragraphs of Proust.”

Although Cassady was friends with Kesey and Kerouac, the two writers met only once, and that was while the Pranksters were in New York on this trip. Kesey and the Pranksters were staying in a vacant Manhattan apartment owned by a cousin of one member of the group. The apartment was in a building on Madison Avenue between 89th and 90th streets. Further was parked in front of the 90th Street Pharmacy on the other side of Madison Avenue for about a week.

Ken and several other Pranksters were eager to meet Jack because they had been deeply influenced by On the Road. I told Kerouac that Kesey was going to be in town and would be in touch with him. Cassady contacted Allen Ginsberg, and the two of them, along with Peter Orlovsky, Allen’s partner, and Peter’s brother Julius, who was one day out of a 14-year stay in a mental institution, drove out to Northport on Long Island to pick up Kerouac and bring him into Manhattan.

Jack was 12 years older than Ken, and there was a marked difference in their energies and interests. Jack had been living in a house with his mother in Northport, although he still had to deal from time to time with the public adulation inspired by the 1957 publication of On the Road. His was a relatively passive life.

[adblock-right-01]

Kesey and the Pranksters, on the other hand, were on an extended high that peaked in New York. According to one of the Pranksters, Ken Babbs, every place they had stopped on the bus trip, they had gotten out their musical instruments, donned their regalia, turned on the cameras and tape recorders, and broken into “spontaneous combustion musical and verbal make-believe shenanigans.” The Pranksters were still doing a version of this in the New York City apartment.

This was the atmosphere into which Kerouac walked. Unlike the intrepid Pranksters, Jack sat quietly on the side, “slightly aloof,” as Babbs told me. They draped a small American flag over Jack’s shoulders, but he took it off, folded it neatly, and placed it on the arm of the couch.

There was absolutely no serious or colorful discussion between Kesey and Kerouac. Jack was never loud, or critical, or indignant. He seemed tired, but he was patient with the Pranksters’ antics. Still, an hour after he came, he left. In the end, he was uncomfortable with Kesey’s overwhelming display of exuberance.

But the Kerouac-Kesey encounter carried a message: Ken Kesey was not a part of the Beat Generation. Thanks to a CIA-funded drug experiment at a veterans hospital, which had introduced Kesey to psychedelic drugs, Kesey instead sparked the Psychedelic Revolution, which spawned the hippie movement. Kesey brought LSD to people’s awareness, and he and the Merry Pranksters spoke of its mind-expanding, life-enhancing properties.

Kerouac was of course not a part of that revolution. What I realized was that he was deeply committed to writing. Kesey was just as deeply committed to living and experiencing the lives of others; writing for him was just a part of living.

The Beats and the Pranksters showed us different ways of opting out of society. They were both countercultural movements. The Beats were trying to change literature, and the Pranksters were trying to change the people and the country. After Sometimes a Great Notion was published in 1964 and Kesey moved into the next chapters of his life, he often said, when anyone asked him what he was doing, “Our job is nothing less than saving the world.” And, “The only true currency is that of the spirit.”

Kesey was, in fact, his own cultural revolution, striving to keep the upbeat, freedom-loving spirit of America alive.

With all that happened to Kesey in the ’60s, why wasn’t he the darling of the East Coast literary world, as Kerouac had been in the ’50s? Kerouac was basically shy when outside his own milieu and in no way a self-promoter. But he lived much of the time in New York or nearby Long Island, and at least during the ’50s was accessible to the media, although he did not seek publicity or present himself well in public. They came to him. On the Road had electrified the literary community and sharply marked the arrival of a new generation, and he made good copy for the newspapers.

Kesey was anything but shy. He embraced people; he gave of himself to others. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest was the debut of a daring new voice, but in the end, Kesey’s profound impact on his generation and those to come was the result of his whole style of life—novels, bus trips, acid tests, public performances, and the like. Also, Kesey didn’t seek out the press and he lived so far away from what earlier journalists called “the ballyhoo belt”—New York City. Besides, as he put it, “fame gets in the way of creativity.”

I remember asking him toward the end of his 1963 visit to New York City what he planned to write next. His answer was that he planned to do a little living next.

Kesey had an open mind, but once he had made up his mind, he stuck to it. People often associate One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest with the movie and Jack Nicholson’s outstanding performance in it. But Kesey never saw it. Shortly before the movie was released, he and Faye met with a studio lawyer to clear up questions related to its future earnings. The lawyer managed to offend both Ken and Faye, and at one point he became so irate with Ken that he yelled, “When the movie comes out, you’ll be the first in line to see it.” Ken just glared at him and swore to himself he would never see it—and he never did.

When I was with him in New York City in 2001, a few months before he died, he still hadn’t seen the movie that so many people associate with him. We were sitting in the Royale Theater with David Stanford, Ken’s editor and longtime friend, and a reporter for The New York Times who was doing a story about Ken. We were watching a revival of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by the Steppenwolf Theatre Company from Chicago. I could tell that Ken was interested in the performance but not very enthusiastic about it. So I asked him, “Ken, what’s the best theatrical performance of Cuckoo’s Nest you’ve ever seen?” Without a moment’s hesitation, he said, “Sacramento High School.” I was really surprised. And then he added, “They caught the ambiance better than anyone before or since.”Age hadn’t changed him or dimmed his perception in any way. He was the same Ken I had come to know so well.

This article is adapted from Sterling Lord’s book, Lord of Publishing.