The world was my oyster. So said my father, anyway, on those nights when he’d been drinking and we were cruising around in his two-tone Buick Riviera. This was the late 1950s in Brewton, Alabama, and Daddy was sending me away to the same boarding school in Rhode Island that he’d attended, Portsmouth Priory, a school run by Benedictine monks. In his mind, he was setting me on a path that would lead to an apartment on Park Avenue, a seat on the Stock Exchange, and an entry in the Social Register. There was nostalgia in his voice when he talked about New York City, where he’d grown up and where he spent a few years after graduating from Portsmouth, skipping college to work at a bank and devote himself to hard, decorous partying. His life as a young man about town, a hanger-on at the fringes of society, was well documented in the scrapbooks that filled a long shelf in our “library,” their pages stuffed with invitations and clippings from gossip columns and photographs taken at nightclubs. I might have been the only kid in Alabama who could name the Deb of the Year in 1938 (Brenda Frazier). Even at the age of 13, however, I understood that the future my father envisioned for me was the one he’d once wanted for himself, but he’d only gotten as far as the Stork Club. If he’d known how to make a go of it in New York, he wouldn’t have been living in a town he disdained, working for his father-in-law, and sidling in and out of the American Legion Hall to wet his whistle.

I went to Portsmouth on a scholarship. It came as news to me that I needed one. My grandfather, Baba, owned two textile mills and a dye plant named after me, Stephen Spinners, where the fabrics were dipped into vats of pungent chemicals. Some of my first memories are of wandering around in the house that Baba built for himself on a piece of land that had once been a pecan orchard. A few years later, my parents built our house next door and filled it with furniture that my mother picked out in one day at W. & J. Sloane in New York. By local standards, both houses were show places, not as grand as some of the old houses in town with their porches and columns, but solid and substantial. We had maids and cooks who wore aprons, and a yardman, Buster, who tended the displays of azaleas and cut the broad lawns with a gang mower pulled behind his Jeep. When my grandmother wanted to go somewhere, Buster put on a chauffeur’s cap and drove her in the big blue Chrysler Imperial. In the summer, we all took the train to Pennsylvania and stayed at my grandparents’ house, the one my mother had grown up in. There were so many kids in the family that we filled most of a Pullman car, and in those years of plenty we took help with us, our maid Ruth and her snaggle-toothed husband, David. The train normally sped right through Brewton, but for us it made a special stop, with sparks flying and steam hissing and the wheels singing on the rails, with the voices of the conductor and the porters ringing out in the sultry darkness. On those nights, my brothers and sisters and I felt just like royalty.

So I could not help knowing that we were better off than most people. In my childish way, I also knew that there was another order of wealth, a world of tycoons in top hats and millionaires with yachts, but I had glimpsed it only in movies and comic books. Maybe because that world wasn’t quite real, and was more than a little ridiculous, it had never occurred to me that I’d actually know people who belonged to it, or that I should care what they thought of me. As my father wanted me to understand, however, there would be rich boys at Portsmouth, and he didn’t want me to seem like a bumpkin. Daddy wanted to squeeze the hayseed out of me, and he spoke with reverence of his own rich schoolmates, pronouncing their names as though they belonged to a race of demigods. One lasting memory of those drives in his Buick is of the urgency in his voice as he tried to impress upon me the importance of learning to move easily in their moneyed orbit.

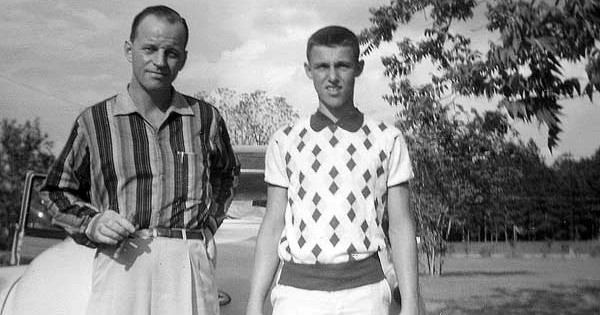

A familiar story: the son is given the task of living out his father’s unfulfilled dream. Daddy took me to buy clothes and taught me how to wear them—how to match the knot of the tie to the collar of the shirt, what sort of collar went with what sort of lapel, how to position the clasp of the garter between the shin bone and the calf muscle. He despaired of my accent, though he’d always done his best to purge it of “y’alls” and “ittents” and other southernisms. He tried to teach me the right way to comb my hair—like Cary Grant, not Elvis. The father who’d once, and only once, thrown me a baseball and said, “Never say I didn’t play ball with you”—this man had now focused his attention on me, and I was flattered. Throughout my childhood, we’d had battles about my clothes and haircuts and my accent, but now I wanted to do as he said. I wanted to please him.

He and my mother drove me to Rhode Island. On the day they delivered me to the school, it took him forever to dress and he fussed over me as if preparing me for a coming-out party. When we passed through the gate and onto the grounds, I felt a kind of relief. The place was nowhere near as grand as I had imagined, just a sprawl of white clapboard buildings, a few of which looked like barracks. And the other boys I saw looked like … boys.

But my father, I could tell, was all nerves. It was strange to see him like that, my father who was usually so utterly sure of himself and so dismissive of everyone else. As I watched him talking to the other parents, to the monks and the masters, I was surprised, and surprised to find that I was also embarrassed. There was too much tooth in his smile, too much eagerness in his laugh, too much Vitalis in his hair.

He must have felt like a failure that day, though I wasn’t thinking that at the time. I just wanted him to get back in the Buick and drive away. Of all the lessons he’d tried to teach me, the one that sank in was the one I learned the day he left me at Portsmouth, a lesson he never intended to teach. I didn’t want ever to have to try to pass myself off as rich, or to pass myself off as anything that I was not.

Put another way, I didn’t want to end up like my father.