The Good Spy: The Life and Death of Robert Ames, By Kai Bird, Crown, 430 pp., $26

In the preface to his 2010 memoir, Crossing Mandelbaum Gate, Kai Bird ruminates about the two “bookends” of his life, the Shoah and the Nakba. The significance of the Shoah, or the Holocaust, owed to his wife’s parents, both survivors. The Nakba, or Catastrophe, is the Arabic term for the establishment of the state of Israel, and its salience emerged from Bird’s youth as the son of an American diplomat posted to a number of Arab capitals, and from Bird’s young adulthood, which included a year at the American University of Beirut. These two touchstones, he writes, enabled him to identify with both sides in the long struggle between Zionism and Palestinian nationalism. One of the interesting things about his new book is his willingness to choose a side.

Like American Prometheus, a biography of J. Robert Oppenheimer for which Bird and co-author Martin J. Sherwin won the Pulitzer Prize in 2006, The Good Spy focuses on an American who had an outsize influence on the fortunes of his homeland: Robert Ames, an intelligence official who specialized in the Middle East from the late 1960s until his death in the 1983 bombing of the U.S. embassy in Beirut. Ames’s choirboy attraction to brutal people makes him a promising choice for a biography, quite apart from the lack of other accounts of his life and the fact that, except within the intelligence community, his memory has largely faded.

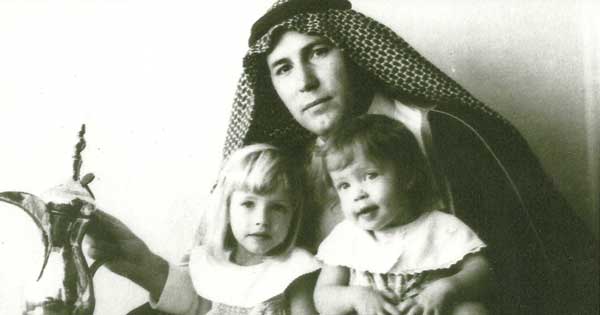

In the decade preceding his death, Ames really did seem larger than life. Tall, handsome, and athletic, he was a teetotaling workaholic who generated an amazing amount of reportage and analysis from the field and a succession of Washington desks. For a man in a high-pressure job, he was also unusually loyal to his family and staff. Bird makes much of Ames’s love for the Middle East and Arab culture, but his preoccupation with his subject’s eagerness to master Arabic becomes irritating: he deploys it to demonstrate a kind of institutional incompetence or cultural bias in the intelligence community but ignores the Cold War context, in which understanding the Soviet Union and its allies was of overriding importance. A huge number of young Americans were then learning Russian, a language no easier than Arabic.

Nevertheless, mastery of Arabic did serve Ames well in the field, giving him a useful feel for the mood on the street and facilitating access to local players who couldn’t speak English. These attributes, combined with his bookishness, helped him forge good working relationships with American diplomats—not always the case in those days—and these ties, in turn, helped advance his career in Washington. Indeed, one of the striking things about

Ames’s career—as reconstructed by Bird and in Ames’s own self-conception—is the mismatch between the Ames who speaks truth to power and is ready to sacrifice his career on its altar and the Ames who is swiftly promoted to positions of increasing authority by his presumably benighted superiors.

But apart from all this, what makes Ames such an attractive biographical subject, at least in Bird’s view, is the tragically unfulfilled possibility of his career. At the same time that, as the national intelligence officer for the Middle East, he was advising senior policymakers in Washington, Ames was also cultivating a relationship with Ali Hassan Salameh, a Palestinian terrorist, playboy, and confidante of Yasser Arafat’s. Bird makes large claims about this dynamic, but overdramatizes it. He appears to believe that the friendship between the two men might ultimately have catalyzed a peace process by facilitating a diplomatic relationship between the United States and the Palestine Liberation Organization. This presumes that Ames’s influence on the Washington policy process would eventually have encouraged the sort of evenhanded U.S. role that, Ames believed, a successful peace process would demand. And from a certain grim standpoint, Bird is safe in making these claims, for both of his protagonists were destroyed by their nemeses: Salameh by the Mossad, which implicated him in the massacre of Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics in 1972, and Ames by Hezbollah in an attack allegedly orchestrated by Imad Mughniyah (himself assassinated in Damascus in 2008, probably by the Israelis). Who, therefore, is to say that events would not have unfolded along the lines that Bird lays out?

Perhaps no one. Disappointingly, Bird documents encounters that suggest influence on Ames’s part, but he apparently did not have access to primary sources that would show what specific positions Ames was advancing in those meetings. One assumes that the evidence is still classified. Ames was in a lot of meetings with principals, and on at least one occasion, the secretary of state sought out his advice. But then, just by virtue of his job title, Ames would have been included in high-level meetings as a matter of course, extending even to those held in the White House Situation Room. The Nixon administration likely saw some utility in the Ames-Salameh channel, both because some deniable interaction with the people around Arafat was seen as potentially valuable, even if not essential, and because Salameh allegedly offered to keep Palestinians from targeting Americans. However, then as now, the Israelis tended to kill terrorists with blood on their hands, and as Bird argues, the U.S. government did not consider Ames’s relationship with Salameh important enough to request that the Mossad not assassinate him—a point on which the Israelis, according to Bird, specifically queried the CIA.

Bird is critical of Israel’s decision to kill Salameh, but one wishes his reasoning were clearer. On the one hand, he derides the decision as an example of the Israeli propensity to think tactically and reflexively, which in this case eliminated a brake on Palestinian terrorists even worse than Salameh. On the other hand, Bird regards the assassination as part of Israel’s strategic and profoundly Machiavellian determination to eliminate Palestinians who might make plausible partners for peace. There are two Israels at work here. The first seems more plausible, although the Israelis would certainly have argued that the net effect of killing Salameh was to weaken Palestinian offensive capabilities, an important tactical gain, especially where strategic victories were frustratingly elusive.

Here Bird jettisons the sympathetic neutrality with which he sought to portray the Arab-Israeli conflict in Crossing Mandelbaum Gate. Readers inclined to see Israel as having stupidly or cynically foreclosed opportunities to reconcile with Palestinian nationalism, and who consider U.S. policy unduly constrained by domestic politics will find comfort in Bird’s book. Indeed, one of Bird’s set pieces, a description of the Phalangist massacres at the Sabra and Shatila camps, does show Israeli policy at its worst. But readers who see Israeli policy in this period as a frequently inept effort to grapple with the emergence of Palestinians as a meaningful player in an already complicated regional framework will find it less satisfying.

Whichever the case, Ames never enjoyed the kind of decisive influence that Bird implies. Nor could he have. The Middle East peace process has always been the province of the White House. Midlevel officials generally have not exercised the kind of clout that Bird attributes to Ames. The political stakes are too high, and as a practical matter, the extent of direct contact between U.S. and Israeli political leaders tends to convince both that they know all they need to know about the other side. Moreover, American intelligence officials are constrained in the kind of policy advice they can offer without appearing to overstep their role in the process, and the bureaucracy, especially in its upper reaches, generally does not advance people perceived to be fundamentally at odds with established policy. And Ames advanced rapidly and apparently felt at home in the corridors of power, even if by virtue of his lesser status, he was not in a position to wield it.

Is this book worth reading? For a sense of what life was like for an intelligence officer in the Middle East and Washington over the course of 20 turbulent years, the answer is yes. And perhaps also as a tribute to an exceptionally inspiring civil servant. The depth of Ames’s bond with Salameh is compelling, as is Bird’s portrait of Salameh himself. It almost made me nostalgic for the days when terrorists drove fancy cars, seduced ingénues, took their drinks shaken not stirred, and hung out with CIA operatives. But for an understanding of the policy process in Washington or of Palestinian politics, there is not much to be gleaned. And as for the question that Bird leaves lingering tantalizingly in the air—would we have an Palestinian-Israeli peace had Ames and Salameh lived—we now know that to the degree there has been progress, it began with Palestinians and Israelis in a Track II process in Oslo in the complete absence of American awareness, let alone participation.