Empire of Sin: A Story of Sex, Jazz, Murder, and the Battle for Modern New Orleans, by Gary Krist, Crown, 432 pp., $26

Several years ago on a Mardi Gras morning in New Orleans, I inadvertently fell in with three dozen or so blue-T-shirted Christian youths as I walked across the levee in the French Quarter. They were setting off to save souls and were pumping each other up in the manner of a football team about to confront a crosstown rival. Some shouted, “C’mon, we can do this!” while others shook their compatriots by the shoulders or punched their fists into open hands. They descended the low rise and plunged into the sodden, costumed crowd. I didn’t follow along—my plans for the day did not involve soul saving—so I never learned whether they recruited any penitents.

Almost since its founding, in 1718, New Orleans has attracted a steady parade of those intent on diverting the misguided down a more virtuous path. (My favorite is still the bearded man who shows up every Mardi Gras, standing placidly amid the mob holding a large sign reading, “Ask Me Why You’ll Burn in Hell.”) Never mind that the reformers have little to show when it comes to concrete evidence of progress in their war on waywardness. This hasn’t slowed them, and I suspect the city’s untiring turpitude will continue to serve as a beacon to reformers for years to come.

Gary Krist’s Empire of Sin is a chronicle of one such extended and unusually successful period of reformist zeal, running from 1890 to 1920. At the end of the 19th century, the city was widely regarded as a corrupt, licentious, and racially confused cesspool of wickedness. And reformers set about cleaning it up.

Standing tall amid the social and political tempest that would follow was a man named Thomas C. Anderson, the most recurrent of several persistent characters in Krist’s narrative. A Scots-Irishman raised in the city’s unruly Irish Channel neighborhood, Anderson began as a bookkeeper but by his 30s had acquired interests in saloons and the nascent oil industry. He soon added sporting gentleman to his résumé, managing boxers and dabbling in horseracing. Anderson was “dapper and always well groomed with his pomaded

reddish-brown hair and carefully waxed mustache,” Krist writes. A photo of Anderson depicts a man of supreme confidence with a mustache that today would incite envy from Williamsburg to Bushwick.

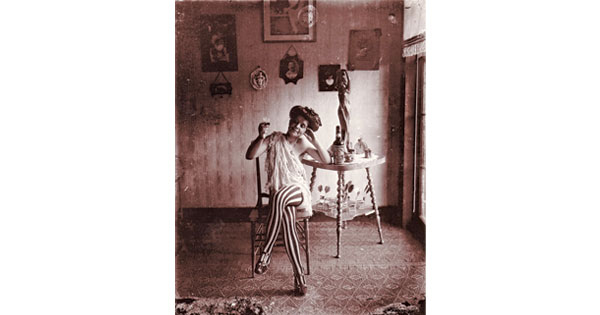

In 1897, when reformers created an 18-block legalized prostitution district called Storyville to sequester vice far from respectable neighborhoods and “pure and noble womanhood,” Anderson was foremost among the wildcatters staking a claim. He opened several businesses in the bordello zone, including the Annex, which served as Storyville’s de facto city hall. Anderson became Storyville’s de facto mayor and hosted an annual Mardi Gras ball in which local prostitutes played the part of the queen and her court.

“Vice and hydrocarbons had proved to be the twin engines of New Orleans’ prosperity,” Krist writes, “and Tom Anderson had a hand in both.” It may come as no surprise to anyone familiar with Louisiana politics that Anderson also was elected to the state legislature.

Anderson looms large in the reader’s mind, but this is no biography. Krist deftly weaves Anderson’s rise and fall into a much broader tale involving race relations, prostitution, jazz, and the underworld of Italian immigrants. This was, after all, a period of considerable ferment. Among the happenings: a light-skinned, Creole New Orleanian named Homer Plessy refused orders to leave a whites-only train car, leading to the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court decision, which codified Jim Crow laws for more than a half century.

Violence within and against Italian immigrants (especially Sicilians) is a darkmotif. Krist recounts the assassination on a dim, rainy street of police chief David C. Hennessy. When asked who shot him before he died, Hennessy replied, “Dagos.” Italians were rounded up and tried. When the acquittal of the first three proved unsatisfactory to city reformers, more than 6,000 agitated New Orleanians rallied and stormed the city jail, resulting in the lynching or shooting of 11 Italians, most of whom hadn’t yet been tried. Their bodies were left on grisly display for the gawking hordes. Afterward, an uptown lawyer instrumental in inciting the bloodthirsty mob declared, “You have today wiped the stain from your city’s name.”

This period also saw the rise of jazz, with cameos by legends like Buddy Bolden, Joe Oliver, Kid Ory, Freddie Keppard, Sidney Bechet, and Louis Armstrong, the last of whom discovered the cornet after being picked up as a teen for misbehavior and sent to a home for wayward youth. Jazz was seen as an outgrowth of urban filth and racial mixing; the local paper railed against it as “demoralizing and degrading” and “wholly forced and unnatural.” Reformers put on the squeeze, and jazz soon dispersed to cities like Chicago and New York.

The demimonde over which Anderson presided became somewhat more demi as the 20th century rolled on: “[T]hose who tried to operate in the old ways now paid a price,” Krist writes. Arrests that once could be dismissed as the costs of doing business became more difficult to slough off. Anderson tried to keep his prostitutes discreet, but undercover investigators had little trouble finding them at his remaining establishments. (“A woman sitting at the next table poked me in the back and winked her eyes,” one of them reported.) Even his status as a Louisiana state legislator didn’t offer Anderson full immunity. His name became a local adjective, and in later political campaigns, reformers warned of a “tomandersonized” atmosphere. In time, Anderson’s political power and that of his cronies waned. “For the first time in a generation, New Orleans’ city government was in the hands of the reformers.”

This was ultimately a Potemkin victory, of course. “New Orleans had not really been cleaned up,” Krist notes in the next chapter. “As in other cities around the country, a visitor … would now have to look slightly harder for a drink, a woman, or a poker game.”

At times, Empire of Sin can lose its thread, and the reform narrative makes for a somewhat rickety superstructure for the engaging tales that Krist recounts. And here and there it can feel like a disjointed but overlapping lecture by a beloved professor fond of storytelling. Yet bit by bit, when viewed from a sufficient height, the mosaic of events, attitudes, and people forms a larger and more informative picture.

What keeps it going are well-crafted vignettes and deftly rendered character profiles, in which reformers aren’t necessarily holy, and their targets are often possessed of considerable charm.

When famed ax-wielding prohibitionist Carrie Nation came to town in 1907, she marched into one of Tom Anderson’s saloons, where she found him awaiting her in his elegant evening clothes. Undeterred, she smote some whiskey glasses on the bar with her ax and then asked, “Want to make some thing of it?”

Anderson bowed, and replied, “Mrs. Nation, the pleasure is all mine.”