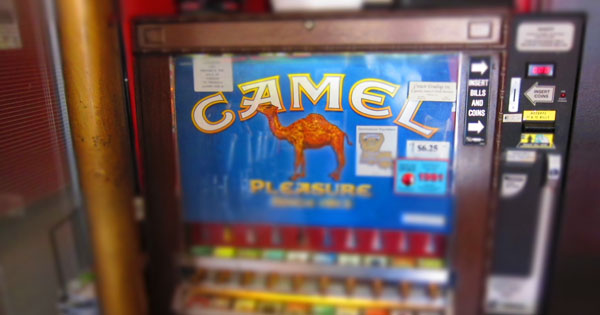

So this happened: New Orleans banned smoking in bars. Until recently, the odds of this occurring seemed about as good as a water slide opening in Nunavut. But on January 30, New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu signed a municipal ordinance that banned cigarettes, cigars, and e-cigs in virtually every bar citywide. The law, which follows a 2007 ban on smoking in restaurants, goes into effect in 90 days, after which New Orleans falls into line with most other major American cities when it comes to smoking indoors.

And that falling into line, more than the loss of indoor smoking itself, seems to aggrieve many of those who opposed the ban. In fact, the loudest grousing I heard came from friends who are nonsmokers. They saw this as an attack on what makes New Orleans New Orleans.

This is, after all, a city where you can not only misbehave badly, but also misbehave baldly. Bars don’t have a closing time, and you can carry your drink down the street to the next bar, possibly behind a brass band that’s snarling traffic. The smoking ban was seen as the first step on a regrettable journey, the final stop of which is a New Orleans indistinguishable from Columbus, Ohio.

“We’re becoming like every other nanny state in America,” wrote one friend on Facebook. “Now that’s the real death of an original American city. I’m telling ya, GoCups are next.”

Behind all the rar-rar-rar on my social media feeds, this is essentially a continuation of the same argument that’s been running here for centuries—neatly summed up by several observers, including Tulane geographer Richard Campanella and Loyola University English professor C.W. Cannon, as “Americanism vs. exceptionalism.”

The Americanists think New Orleans is more or less like the rest of the nation, albeit with a few cosmetic differences. The city owes its reputation in part, Campanella notes, to visitors and travel writers zeroing in on the few differences while ignoring the many similarities. (“Be sure to check out the new Pei Wei on North Carrolton Ave.,” wrote no guidebook ever.) And Americanists tend to believe the city’s fondness for embracing its old habits and differences holds it back. In the run-up to the smoking ban, one city councilor noted that 27 conventions had refused to convene here because of indoor smoking. Adopting best practices from elsewhere is the way to attract more visitors, residents, and investment, and move the city forward.

The exceptionalists argue the opposite. They see the quirks of New Orleans—smoking inside, drinking outside, music everywhere—as worth celebrating and defending. They argue that the city’s laissez-faire approach to vice is at the heart of the city’s culture, and that’s likely to draw more than enough free-spending visitors to replace those 27 conventions. The pride of being apart from the rest of the country was nicely captured in an anecdote I heard at a literary conference a few years back. A writer from Jamaica was talking about his first trip to the city, and said that his friends back home assured him he’d love it. “It’s got great food and music,” they told him. “And it’s so close to America!” The audience howled.

Throughout the city’s nearly 300-year history, New Orleanians and visitors alike have celebrated its cultural idiosyncrasies, starting with those who marveled at the French Catholicism and curious food at the beginning of the 19th century, and followed by those who waxed romantically about remnants of lapsed Creole culture at the end. In the last century, New Orleans was lauded for creating a world where jazz was born and sin reigned immortal.

The Americanists won this round in passing the smoking ban, but in some ways this was an exception. A couple years back there was an effort to dampen the city’s second line parades—essentially weekly roving street parties, with live music and dancing and unlicensed vendors selling $2 beers out of rolling coolers. But this was shelved following local uproar. Second lines these days continue pretty much as they have for decades.

Likewise, the city has been grappling over what the Americanists call “noise” and exceptionalists call “music.” Every large city in America has had to deal with amplified music spilling out of clubs late at night. But no other city is so closely tied to music as New Orleans. Efforts last year to pass a one-size-fits-all citywide noise ordinance were tabled after fierce blowback, which included a small army of brass instrument musicians parading loudly through city council chambers.

I’m a nonsmoker, and I’m rather ambivalent about the smoking ban. I’m all for it if this means healthier musicians and bartenders, and a wider selection of bars to watch the Saints without feeling like I’ve walked into a “Pittsburgh 1963” Instagram filter. But I’m totally opposed to the smoking ban if it’s a shot across the bow, and signals a larger push on curbing music and marching and drinking in the street.

Come April, I’ll watch how this all plays out from a nearby barstool. A number of bar owners believe that, despite evidence to the contrary, the smoking ban will ruin them. I plan to help prove them wrong by stepping up my drinking. It seems the least I can do.