“Can I have a Band-Aid?” There was a time when, in response to such a request from one of my small children, I would have looked for evidence of bleeding. But then I realized it’s not about the blood. It’s about a child’s growing understanding of how the human body functions.

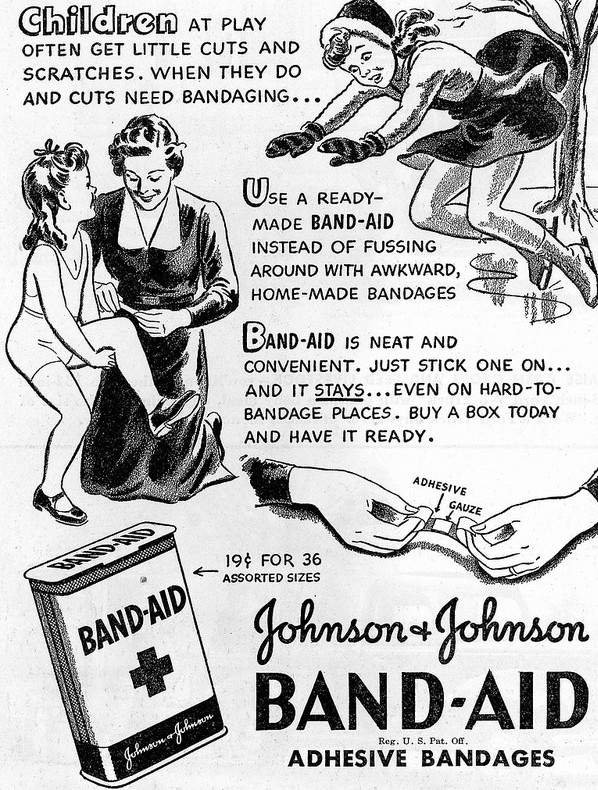

The urge to stick an adhesive bandage on even the faintest of scratches—or imaginary ones—appears to be universal among toddlers. Parenting blogs are rife with anguished reports of children with “a half-box a day habit” whose parents blame companies that stamp the strips with the ubiquitous, mouthless Hello Kitty or characters like Dora the Explorer and SpongeBob Squarepants.

But the childhood fascination with adhesive bandages almost certainly predates the branding of Band-Aids, which, according to the manufacturer’s history, were first sold in 1920 and first decorated in 1956. As psychoanalyst Selma H. Fraiberg wrote in 1959 in her book The Magic Years: Understanding and Handling the Problems of Early Childhood, the fuss over faint grazes and scrapes typically coincides with the realization, in the third year of life, that a child has become an individual person. “The more conscious the child becomes of himself as a person,” she wrote, “the more he values this body which encloses and contains his personality.”

How does a child perceive the inside of his or her body? “Until a surprisingly late age, even eight or nine,” the child “imagines his body as a hollow organ, encased in skin,” Fraiberg wrote. “It is all ‘stomach’ in his imagination. … And since the child, at an early age, has discovered that if his skin is scratched or cut, blood will appear, he visualizes the interior of his body as a kind of reservoir in which blood, food and wastes are somehow contained.”

Research published last year suggests that children understand the functioning of their own vital organs earlier than Fraiberg postulated 56 years ago. Georgia Panagiotaki and Gavin Nobes, clinical psychologists at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England, compared attitudes toward the human body among 188 children between the ages of four and seven from three cultures: rural Pakistani Muslim, British Muslim, and white British.

By age four or five, the researchers found, children in all three cultural groups knew the location of organs—heart, brain, lungs, blood, and stomach—and their knowledge was expanding. Although the British children were better able to explain the biological function of vital organs (because they learn about them earlier in school) the Pakistani Muslim children “were considerably better at explaining that organs are important for keeping us alive,” say the authors. “These children did not know—or could not explain—what the vital organs are for, but knew that without them one would not be able to survive.”

The reason for their greater understanding, the authors suggest, is that the Pakistani Muslim children were more likely to observe or participate in the killing of domestic animals for religious or other purposes; thus, they were more likely to understand what happens to the body when the heart or blood ceases working. By contrast, the British children’s contact with animals was limited to “looking after pets and visits to the zoo.” As Panagiotaki said in a press release, “British children are quite protected, maybe too much so, from discussions about life and death, subjects that can be seen by adults as difficult to talk about.”

Perhaps it is also the difficulty of talking about life and death that prompts children to seek the consolation of an adhesive bandage at the slightest hint of blood. After all, as others have observed, the ritual of applying one usually takes place in a parent’s arms, where wordless cuddles offer more comfort than Hello Kitty ever can. That view is reiterated by Lauri Nummenmaa, a cognitive neuroscientist at Aalto University in Espoo, Finland, and the author of a study on how we experience emotions in different parts of our bodies. As he explained to me via email, placing a Band-Aid on a tiny cut can provide a strong placebo effect, whereby the attention itself is beneficial. “The act of putting on the plaster with nice colors and pictures distracts the mind from the pain, and again we know that such refocusing of attention away from the pain itself is a powerful way to alleviate pain.”