As the leading public intellectual of the Civil War era, Ralph Waldo Emerson built his reputation on the lecture circuit, traveling by train, steamboat, and stage from his country seat in Concord, Massachusetts, to rising Yankee outposts all over the “nervous, rocky West,” and dispensing inspirational calls for self-reliance and the fulfillment of “American genius.” Since the 1850s, he has been known far and wide as the “Sage of Concord,” a title bestowed by his friend Margaret Fuller when he was still a parochial figure speaking chiefly to audiences in New England and the Northeast.

Critics ridiculed Fuller’s tribute as a fawning act of “hero-worship,” but her sobriquet reveals an important insight into Emerson’s career as an “American prophet.” Concord, the ancestral home of his forebears and his permanent residence after 1834, was where, as much as Boston, New York, or Philadelphia, Emerson forged his style as a speaker and articulated at its most radical and visionary his ideal of free, self-defining individuals in a democratic society. Emerson took his message to his neighbors year after year, from his first outings to his final days at the lectern, and they eventually embraced him for that service, even when they struggled to grasp what he was saying. One woman admitted that she didn’t understand a word of Emerson’s lectures but went anyway because “I like to … see him stand up there and look as if he thought every one was as good as he was.”

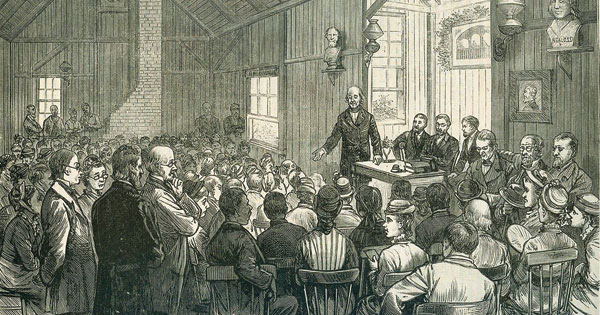

That homely anecdote evokes an image of Concord as the classic small town, where democracy was a vital force in everyday life, with inhabitants of every class and condition—bankers and blacksmiths, farmers and laborers, manufacturers and operatives—mingling together in shops, churches, and town meetings. There, we nostalgically imagine, lofty thinkers tested their boldest ideas in daily intercourse with common folk and in occasional addresses to neighbors thirsting for knowledge and enlightenment. Emerson himself contributed to this notion by celebrating Concord as an ideal combination of country and city, nature and culture, solitude and society. But in the decades after the high-minded graduate of Harvard Divinity School abandoned the security of a well-paying pulpit in an elite Unitarian church in Boston for the risks of freelance lecturing, Concord was itself a place in flux.

Although it numbered only 2,000 inhabitants when Emerson moved in and never reached 2,500 (the Census Bureau’s threshold for urbanity) before the Civil War, the community stirred with change, as the townspeople left behind the small, ordered society founded by Puritans and defended by Minutemen and entered an expansive, new world of capitalism and democracy offering unprecedented opportunities and unsettling uncertainties. The novel circumstances at once widened horizons, challenged inherited beliefs, and generated a flood of information and ideas from all over the globe. How to cope with this torrent and channel it to good use? Anxious, striving New Englanders were eager to know how best to thrive in those new, uncertain times. They constituted a ready audience for such aspiring lecturers as Emerson, who would reinvent himself in the “secular pulpit” of the lyceum movement and offer the lessons of his wide reading, extensive travels, and hard-won experience to listeners embarked on similar journeys.

Concord in the age of Emerson was therefore not the pastoral place fit for poets and philosophers long enshrined in popular memory. It was rather a crucible of change, where new roles and identities were forged for citizens and scholars alike. On April 19, 1775, the town had supplied the stage on which the Revolutionary War began, when Minutemen confronted British Regulars at the Old North Bridge and, in Emerson’s words, fired “the shot heard round the world.” Six decades later, Concord provided a setting for another momentous transition in American life: the making of the public intellectual in a democratic society. Emerson, followed by his sometime disciple Henry David Thoreau, would test out the possibilities of that figure in numerous conversations with his neighbors at the Concord Lyceum, a local organization with an agenda of its own. In that role he was no longer the preacher expounding and applying a timeless gospel to the faithful but a man speaking from one soul to another in the urgency of the moment. He not only instructed but also responded to the concerns of an audience. He learned to be flexible. He adjusted to shifting expectations. He initiated change. Concord helped make Emerson as a public speaker, and he, in turn, left his imprint on the town, helping advance a broad-based movement for continuing education and self-improvement.

Emerson delivered more than 100 lectures to the townspeople over the course of five decades. The talks were much the same as those he gave in Boston and elsewhere, but the arrangements were different. In the city, he hired a hall, advertised a program, and sold tickets to whoever was willing to pay; like other entrepreneurs of the day, he sold his wares in an impersonal marketplace. Not so in Concord, where the squire of Coolidge Castle, as he dubbed his house on the Cambridge Turnpike just outside the village, gave his discourses at no charge. He did not come before the townspeople as an independent agent; now he spoke under the auspices of the Lyceum. Although he made his living as a professional lecturer, he was merely one among equals in town, participating in a forum full of volunteers. The audience was likewise more inclusive than in Boston. Members of the Lyceum could bring their wives and children, and tickets were available to any inhabitant upon request. Concord residents thus had an extraordinary opportunity: they got to hear, at no charge, most of the lectures the Reverend Emerson—he did not drop the title until 1840—gave to the crowds flocking into the Masonic Temple in Boston every winter. If Emerson was in his radical heyday in these presentations, no one in Concord need be unaware.

[adblock-right-01]

Emerson’s first public lecture was “The Uses of Natural History.” Given in early November 1833, just four weeks after his return from an intellectually formative trip to Europe, it was well suited to its audience, the Boston Society of Natural History. He repeated it in Concord on New Year’s Day, 1835—the first of his presentations to the Lyceum whose title is definitely known. Here, too, the lecture fit the bill, for no subject was of greater interest to the members in the group’s earliest years. To disseminate the latest knowledge about science and technology was why the lyceum movement had originated in Connecticut and Massachusetts in the first place.

Its impetus had come from a visionary schoolmaster named Josiah Holbrook, who developed a passion for science after attending Professor Benjamin Silliman’s lectures on chemistry and geology at Yale. Intent on putting such knowledge into practical use, Holbrook opened an “agricultural seminary” on his family’s farm in Derby, Connecticut, where young men combined manual labor with the study of natural science. The enterprise was on the verge of collapse in 1825, when Holbrook read an article about the British mechanics’ institutes, which aimed to expose workingmen to the branches of science so that they could cooperate more effectively with employers in the pursuit of technological progress and thereby improve their wages and status. Traditionalists in England were appalled at the prospect of teaching algebra and chemistry to laborers, for fear that education would blur class lines, raise the sights of workers, and eventually lead to “a state of anarchy.” Holbrook seized on the idea, adapted it to American circumstances, and made it the mission of his life.

Holbrook’s plan called for the establishment of “associations for mutual instruction in the sciences, and in useful knowledge generally.” The target audience was young men in need of “an economical and practical education,” who would come together for lessons in “Mechanics, Hydrostatics, Pneumatics, Chemistry, Mineralogy, Botany” and “any branch of the Mathematics, History, Political Economy, or any political, intellectual, or moral subject.” Holbrook treated all knowledge as “useful” if it could be incorporated into daily life, aiming to “diffuse” it not just to workingmen but “through the community generally.” Central to this effort were the sponsorship of lectures and the assembling of books, laboratory equipment (then called “apparatus for illustrating the sciences”), and collections of minerals. Participants in the associations would learn both by listening and by doing.

Holbrook wrote up his scheme, published it in an educational journal, and then took to the road in a campaign to plant lyceums all over the land. The “Lyceum” was the name of the building in which Silliman conducted the “scientific demonstrations” Holbrook had attended in New Haven. It now came to signify the new association that would sponsor lectures and experiments for aspiring Americans. Holbrook headed for the manufacturing villages rapidly expanding across the New England countryside, such as the appropriately named Millbury, Massachusetts. There, a civic-minded gun maker gathered together the workers from his armory to hear Holbrook’s plan, and they were quickly persuaded to form “Millbury Branch No. 1” of “the American Lyceum.” Within a year Holbrook claimed to have inspired the creation of 50 to 60 associations. The last week of October 1828 found him in Concord, lecturing on geology to a “large audience anxious to profit by his instructions.” A week later the Concord Debating Club took up the question: “Would it not be expedient to establish a lyceum in this town?” The affirmative side prevailed. By late November the organization of a Concord lyceum appeared to be a done deal.

But the initiative faltered. When a “large and respectable” body of citizens came together to implement Holbrook’s design, it confronted two stumbling blocks. One major objection was the supposition that Concord could never come up with “a sufficient number of lecturers, especially among our own people,” to accomplish the worthy goal of disseminating useful knowledge. The second disagreement turned on the question of dues. Under Holbrook’s model, the annual membership fee would be $2 for adults and half as much for men under 18. That policy did not go over well with people who lived outside Concord village. Surely, they argued, heavy snows and storms in the winter would prevent some folks from attending all the lectures. It was unfair to impose the same dues on them as on residents of the town center. The plea went nowhere. Only after the Lyceum fell short in its bid for subscribers were fees set at half-price for inhabitants in the outer districts. Fifty-seven males signed up, the oldest a toughened saddler of 81, the youngest 12-year-old Ebenezer Rockwood Hoar, future attorney general of the United States. No matter where they lived, each member was entitled to bring “two ladies” to the lectures and, “if married, his children in addition.”

Science was very much on the members’ minds when the Concord Lyceum went into operation. The inaugural lecture was an attack on “popular superstitions” by the Unitarian minister Bernard Whitman, from the textile-manufacturing town of Waltham. Presented to some 300 persons in the Court House on the common, this discourse took at least two hours to expose the “ignorance of correct reasoning” that gave rise to so many traditional beliefs, from the foolish faith in lucky days and credulous fear of ghosts to the ill-considered practice of timing farming chores, such as slaughtering swine, by the phases of the moon. “The moon has no more to do with … hogs,” the faithful shepherd opined, “than the Pope of Rome.” Eleven months later the Lyceum celebrated the commencement of its second season of lectures with an address by Cornelius C. Felton, the new tutor of Latin at Harvard, who took the audience on a long historical tour of “the Progress, Dignity, and Importance of Knowledge” from the Greeks and Romans through the Middle Ages and Renaissance down to the contemporary activities of “Mechanics’ Institutes and Lyceums.”

These performances were aimed at fostering scientific reasoning; other talks delved into specific fields of inquiry, from astronomy, botany, and chemistry to geology, mechanics, and zoology. Altogether, the Lyceum hosted 143 lectures in its first five years; 50 of them discussed science or technology. No other topic came close. That intellectual fare evidently pleased the townspeople. Membership in the Lyceum doubled from 57 in 1829 to 118 in 1832, and so many inhabitants took up the offer of free tickets to the lectures that paying subscribers complained they could not find seats.

As it turned out, the fears that Concord could not supply enough lecturers proved groundless. Twenty-seven local men volunteered in these early years, delivering 82 addresses, more than half of the total number through 1834. That was a notable achievement. But it is not altogether clear that the self-taught citizens, reading up on a subject to inform the neighbors, diffused as much “useful knowledge” as Josiah Holbrook hoped.

Consider the case of Nehemiah Ball, a tanner who appeared before the Lyceum 12 times from 1829 to 1834, more than anyone else. Ball had grown up on a hardscrabble farm, learned the craft of tanning without a formal apprenticeship, and entered the leather business with his brother-in-law. Luckily, he married well, and he parlayed that good fortune into lucrative investments. One contemporary recalled him as a pompous, calculating, formal man who was “never known to make a joke,” and insofar as he ever appreciated the wit of others, could summon up little more than “a grim smile” or “a feeble chuckle.” The one thing about which Ball felt passionate was education, for which he “spared nothing” in raising his children, including his daughters. He was equally zealous about educating himself and his neighbors on the subject of natural history.

One of his lectures, on the animal kingdom, was illustrated with a magic lantern projecting images of “every known species of ape, monkey and baboon” onto a white sheet, as Ball set forth “a very precise and accurate statement of their length from the tip of the nose to the insertion of the tail.” To one teenager in the audience, the future lawyer John Shepard Keyes, the presentation was ludicrous. “This is a very ferocious animal,” Ball would supposedly say as the image of a lion appeared before everyone’s eyes. The speaker punctuated his remarks with a frequent refrain: “I apprehend.” That “I apprehend,” Keyes recalled decades later, “became a byword among the young people of that day, who could hardly keep from laughing in his face at its constant repetition, notwithstanding the eminent gravity with which it prefaced his conclusions.”

Then there was the medical student Edward Jarvis, lecturing about the “anatomy and physiology of vegetables” in May 1829. At age 26, the Harvard graduate had long cultivated the study of botany as a hobby, but the prospect of sharing his knowledge with the Lyceum audience was profoundly unnerving. For days, in between medical lessons in Boston, Jarvis pored over the authorities, notably Linnaeus and Humphry Davy, and prepared his lecture “with much care.” He wrote it out, copied it, and corrected it. On the day of the meeting he went over the text again and again, without alleviating his anxiety. “I felt quite uneasy, could think or talk of nothing else.” Jarvis showed up in the lecture hall to find the room “nearly full,” and as he approached the lectern, “the people seemed to me an indistinct mass. I could not distinguish any.” Yet, when he began to speak, the words flowed. He had been instructed to “be brief,” but the first part of the talk—a discussion of anatomy—took some 40 minutes, and then there was the account of physiology left to go. Luckily, nobody was squirming in the seats: “The audience were particularly silent and attentive.” The debut proved a success, and Jarvis would address the Lyceum nine times through 1834, second only to Ball.

Emerson’s “Uses of Natural History” lecture may well have sent a fresh breeze into the room. Unlike other speakers, Emerson grasped that a merely factual presentation would not do. It was imperative to establish a relation between the listeners and the subject. He thus began with the proposition that humans were drawn, by the very circumstances of their being, to study the natural world. How else could they get a subsistence? And how could they resist nature’s aesthetic appeal? “The beauty of the world is a perpetual invitation to the study of the world.” So Emerson had concluded from the emotional epiphany he had experienced while visiting Paris’s Jardin des Plantes, the vast botanical and zoological garden displaying the “inexhaustible gigantic riches of nature.” There he had felt profoundly, at the core of his being, the interconnection among all living things, from “the very worm” and “the crawling scorpions” to himself. A relation to nature was thus not so much utilitarian—the premise of the lyceum movement—as fundamental, built into the very constitution of man.

On this basis Emerson proceeded to lay out the advantages to be gained from the study of natural history: it was good for your health to be outdoors in the “fresh and fragrant fields”; it was equally good for your mind and character, training the intellect to be “exact, quick to discriminate between the similar and the same, and greedy of truth.” The knowledge thereby gained would directly serve the economical needs of mankind for “food, clothing, fuel, furniture, and arms.” Most lyceum lecturers would have ended there. Not Emerson. For him, the great advantage to studying nature was the sheer “delight which springs from the contemplation of this truth”: “the knowledge itself, is the highest benefit,” for it promised to “explain man to himself.” “Is there not a secret sympathy which connects man to all the animate and to all the inanimate beings around him?” In effect, Emerson suggested, the aims of the lyceum were too low. The truths of science mattered for their own sake and not merely for the technological advances and the economic benefits they conferred.

By the early 1830s the Concord Lyceum had grown into a lively center of cultural life. On the annual calendar of activities geared to a mixed population of villagers and farmers, the lecture season began just after fall harvest and closed by spring planting. In those months, rural residents could find the time to travel into the center on Wednesday evenings for a varied program of “Lectures, Discussions, and Instrumental Music.” Soon after its formation, the Lyceum had merged with the local debating club and broadened its scope to include regular forensic exercises. In a republic where office holding was no longer restricted to a well-educated elite and where politics was a constant topic of conversation, men of ambition sought to cultivate skills in public speaking. At the Lyceum they could inform themselves on the pressing issues of the day and practice the arts of persuasion. To avoid partisanship, individuals were expected to take a side and argue a case, no matter what their personal opinions. The presiding officer would decide the question.

On these ground rules the members took up the most divisive controversies of the Jacksonian age. “Whether Georgia has a right to extend her laws over the Indians within the limits of her state?” That was the question in November 1830, as the Cherokee Indians were struggling to prevent that state from imposing its sovereignty over them. The verdict was no. “Is the Union threatened by the present aspect of affairs?” “With much spirit” the participants considered the gathering confrontation between South Carolina and the federal government in November 1832, about to explode into the Nullification Crisis. No conclusion. Should capital punishment be abolished? No. “Would it be an act of humanity to emancipate at once, all the slaves in the United States?” Undecided. “Does the light of nature teach the immortality of the soul?” Yes. In theory, the outcome of these debates turned on the rhetorical performance of the disputants and not on the substance of the questions. In practice, the results favored the Unitarian and Whig sentiments of the majority of members.

The debates invariably came first, followed by an interval in which the Concord Band played instrumental music. In Emerson’s view, these exercises were merely preliminaries to the main business of the evening: the presentation of lectures. But that high purpose was increasingly being forgotten. After two years at the podium, the idealistic Emerson felt constrained by the pinched agenda and the paltry record of the lyceum movement. Here was a fast-growing institution with infinite potential to inspire people with fresh ideas and new life. Once, that exalted role had been performed by the clergy, who were, for the founders of New England, “the oracle from which went forth decrees to the people.” But those days were gone, and having given up his perch at Boston’s Second Church, this descendant of Puritan preachers looked for the “lecture-room” to replace the pulpit as “the great organ” of popular instruction. Unfortunately, he told a young admirer in Concord, too many of “our common lyceums” fell short of their great promise, with speakers often presenting “superficial” notions on the “easiest subjects” for no better reason than to fill up a season’s schedule. Enough of this routine “manufacturing”! If lectures are to secure “permanent value,” Emerson demanded, men must hold forth on things that “interest them—upon a subject that the time, the age, calls forth—upon a subject which has not been written upon before, or else they must treat it in a new way.”

[adblock-left-01]

Emerson captured a new mood. His challenge to the narrow utilitarianism of the Lyceum coincided with the members’ gradual shift away from scientific inquiry. Between 1835 and 1839 the society continued to mount a heavy schedule of lectures, some two dozen a year. But science and technology now competed with other subjects for attention. Of the 118 lectures given in the latter 1830s, 18 focused on science and technology, 15 on historical subjects. Interest in science diminished still more between 1840 and 1845: only eight lectures took up the subject.

Into the space vacated by lecturers on science and technology flowed speakers on biography as well as history, and on economics, law, politics, and contemporary affairs. The programs examined “the character of the Indians” one week, the “life of Sir Walter Raleigh” the next; practical accounts of tariffs and manufactures were followed by treatments of the conditions of modern Greece, the history of Poland, and Egyptian hieroglyphics. One area of inquiry covered a miscellany of topics distinctive only for the lecturer who discussed them. This special category for Emerson steadily gained in importance, accounting for eight percent of all lectures in the late 1830s and double that share in the first half of the 1840s. At first glance, local speakers were still holding their own at the lectern, giving more than half of all lectures between 1835 and 1839 and 44 percent in the next half-decade. But take Emerson out of the picture and Concord inhabitants occupy the podium in lesser numbers: 18 from 1835 to 1839 and 10 from 1840 to 1844. By 1845 locals accounted for but one in 10 lectures, about the same share as at the lyceum in Salem, Massachusetts, where Nathaniel Hawthorne would become curator. Taking their place was a growing corps of professionals recruited by the group’s officers and paid anywhere from $3 to $10 per appearance (the latter sum equivalent to an honorarium of $325 today).

Well before outsiders took over the platform, the Concord Lyceum pursued a course increasingly at odds with public sentiments. From the start, the organization called itself nonpartisan and nonsectarian, and its curators took care to keep controversial speakers off the platform. It was one thing to debate hot topics for the sake of argument, quite another to advocate a divisive position under Lyceum auspices. The group thus patronized mainstream views. Agents of the American Colonization Society twice made the case for freeing slaves and sending them back to Africa, but no advocates for the immediate abolition of slavery, not even William Lloyd Garrison or Wendell Phillips, a stage drive away in Boston, spoke to the Lyceum during the 1830s. Such constraints were usually tacit, but occasionally a group would make its preferences plain, as the Salem Lyceum did in 1837 when it invited Emerson to lecture on any subject he wished, “provided no allusions are made to religious controversy, or other exciting topics upon which the public mind is honestly divided.” He declined.

Concord policed its platform by favoring speakers with a predictable point of view. Clergymen came before the local audience more often than any other occupational group, but one denomination stood out. Unitarians were rapidly losing support in eastern Massachusetts, especially after voters ended state support for religion in 1833. But ministers of the liberal faith continued to reach a broad audience through the Lyceum. Two out of three clerical lecturers in Concord were Unitarians. Some, like the Reverend Bernard Whitman, were not shy about their opinions. In his inaugural lecture, he declared that popular superstitions, including the conviction that a sinner could be converted to Christ in a single instant, demonstrated “ignorance of true religion.” That view surely did not please the evangelicals in the audience.

The politics behind the Lyceum proved even more explosive. The Concord association launched its activities just a few months before John Quincy Adams was obliged to turn over the White House to the populist Democrat Andrew Jackson. Concord’s voters had nearly unanimously supported the state’s favorite son, with only four citizens dissenting. In the wake of that calamity, the leaders of the Lyceum quietly promoted much the same agenda as the town’s emergent Whigs. With good reason: they were pretty much the same people. Ever since the 1820s these merchants, manufacturers, lawyers, and gentleman farmers had been altering the economic landscape and transforming the everyday lives of their neighbors by integrating the town ever more deeply into metropolitan, regional, and national markets. They pushed for agricultural reforms that would make farming more efficient, commercial, and profitable. They speculated on land and supplied mortgages to the enterprising and the desperate alike. They founded banks and insurance companies and did a cash business in their stores. They would soon be bringing the railroad to town. Not surprisingly, these businessmen and professionals were the biggest beneficiaries of the dramatic changes, which heightened inequality, sharpened class divisions, and splintered the town into competing factions suspicious of one another. Yet these agents of capitalist revolution clung to an inherited rhetoric of community, even as they pulled apart the older fabric of life.

The Lyceum embodied that contradiction. The lectures were meant to break up older ways of thinking and acting—the ancient lore behind moon farming and other folk practices—and to encourage more productive uses of labor and leisure. Instead of haunting taverns and relaxing with neighbors, farmers and mechanics were urged to improve their minds in rational recreation. Attending lectures at the Lyceum and reading at home, these industrious inhabitants would acquire valuable information and skills for use at work. Even more important, they would cultivate the mental discipline essential to continuous growth and upward mobility in a capitalist world of relentless change. This message of self-help, along with support for Whig economic policies at the state and national levels, forms the leitmotif of the lectures, with few explicit voices of dissent. Hardly a Democrat appeared at the podium, even though, from 1834 on, Concord was divided bitterly over public policies and experienced its own populist uprising against the very men who had long dominated the town.

Naïvely, the leaders of the Concord Lyceum anticipated that the steady chorus of lectures favoring the culture of capitalism would build unity. But by 1837, they were fighting for their political lives. In an election-eve appeal, they sought to put the Lyceum to partisan advantage. “Who have been the leaders of every project for the benefit of the town,” demanded the Yeoman’s Gazette, now an organ of the Whigs, “—whose names are at the head of every society for the promotion of philanthropy?” The opposing paper, the Democratic Concord Freeman, rejected the premise. Public-spirited? Hardly. “Who turns our Lyceum into a Whig caucus, puts down the discussion of all such questions and the attendance of all such lecturers as they do not like?”

The Concord Lyceum weathered the storm, although annual membership fell from a peak of 118 in 1832 to 55 or 60 in the late 1830s, about the same number as at its founding. The group kept up its annual programs of lectures and discussions at a time when the lyceum movement was static and many local chapters were closing up shop. Emerson’s lectures were a bonus, but the Concord Lyceum, like those elsewhere, faced growing competition for the leisure time and dollars of its inhabitants. Concerts, circuses, and magicians came to town, offering popular entertainment rather than useful information; freelance lecturers against slavery and for temperance found platforms outside the Lyceum and appealed to reform sentiments.

As the first decades of the Concord Lyceum make plain, continuing education can never seal itself off from the raucous voices, the vociferous conflicts, and the varied tastes of ordinary people in a democratic society—what Emerson once characterized as “the rough, spontaneous conversation” of men in the streets. Even as the Lyceum aspired to disseminate knowledge and refine manners, it had to contend with such performers as Signor Blitz, “the most laughable and greatest of all magicians,” whose feats of ventriloquism and prestidigitation treated the natural world as a source of marvel and mystery. Where Nehemiah Ball and Edward Jarvis instructed lyceum-goers in the rational laws of nature, Blitz and his fellow performers entertained crowds with astounding displays of occult knowledge and secret skills. Undoubtedly, many townspeople patronized both the lectures and the shows. Antebellum Concord sustained a variegated, at times undiscriminating culture.

Emerson lived through the phases of the lyceum—mechanics’ institute, Whig speakers’ bureau, reform platform, and entertainment medium—without explicitly commenting on the transitions. Even so, it is tempting to suggest that he played a crucial role in breaking down the limitations on speech at the Concord Lyceum and opening it up to the most expansive ideas of the age. In late December 1842 the organization finally dropped its bar on abolitionism and invited Wendell Phillips to address the townspeople. Still early in his career as an antislavery activist, Phillips had recently inflamed public opinion with his rhetorical assaults on northerners’ support of the “Slave Power” and cooperation in returning fugitive slaves to the South, as required by federal law. “My curse be on the Constitution of these United States,” he thundered from the pages of the Liberator.

Phillips’s appearance, the first of three talks he would give in Concord through 1845, marked a turning point in local discussion of slavery, and came about thanks to a new openness among Lyceum members to the intellectual discontent and spirit of reform swirling throughout New England. By the early 1840s, some of the most progressive thinkers of the times were traveling to Concord and holding forth at the Lyceum: besides Phillips, there were the erstwhile Transcendentalist ministers Orestes Brownson, James Freeman Clarke, and Theodore Parker, Democratic politician and historian George Bancroft, newspaper editor Horace Greeley, and utopians Bronson Alcott and Charles Lane reporting on their alternative community at Fruitlands. Several locals, notably Emerson and Thoreau, filled out the season. The mid-1840s saw an ongoing school of reform.

After the mid-1840s the Lyceum dropped the spotlight on reform and no longer featured abolitionists; when Wendell Phillips returned to its platform in 1851, it was to discuss the “Lost Arts” of antiquity—the achievements in chemistry, metallurgy, and physics—that were being rediscovered by contemporary scientists. But controversial issues did not vanish altogether. Women’s rights gained a hearing, with the writer and activist Elizabeth Oakes Smith, the first female speaker to appear before the townspeople, taking the lectern in 1851. A feminist, Smith gave her lecture, “Womanhood,” in the same season as Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes (“Love of Nature”), Henry David Thoreau (“Excursion to Canada”), and Thomas Wentworth Higginson (“Muhammad”); others spoke on geography and history, California, Falstaff, and Lorna Doone. Even the redoubtable Edward Jarvis was back with “The Causes of Insanity,” a discourse on his new area of expertise.

But lecturing was fast becoming a profession for dedicated performers, such as Emerson, on a national circuit. When the Reverend Barzillai Frost mounted the podium in the mid-1850s to deliver “Bleeding Kansas,” he felt compelled to apologize in advance for his defects. “In the present stage of popular Lecturing,” he noted, “gentlemen of the finest talents and culture devote their whole time to it as a profession.” But he was speaking for free, to help the cash-strapped Lyceum fill out its program. “So you must depend upon charity,” Frost mused, “and as beggars cannot be choosers.”

Emerson’s dream of the public lecture as a “secular pulpit,” with impassioned speakers inspiring earnest men and women with prophetic discourses, was as visionary as Josiah Holbrook’s scheme for a national network in the cause of scientific instruction. As a venture in adult education, dependent at first on volunteers to occupy the podium and fill the seats, the Concord Lyceum inevitably reflected the varied interests and the competing agendas of the citizens it served. Still, viewed from a time when online courses and commercial e-books bid to be the latest advances in continuing education, one can only admire the self-improving zeal that motivated the inhabitants of Concord in the early 19th century to spend Wednesday evenings in a crowded schoolhouse listening to Edward Jarvis and Nehemiah Ball hold forth on the vegetable and animal kingdoms, and perhaps wondering when the next traveling circus would come to town.