On a sunny day this past June, I stood with hundreds of restless, excited Hamilton-lovers in front of the Richard Rodgers Theatre on West 46th Street in Manhattan, waiting for the Ham4Ham show, a brief weekly performance held before Wednesday matinees of the musical. June 2016 was the month of peak Hamiltonmania. The asking price for a single orchestra ticket was well into five figures. People were camping out for days on end in the cancellation line for just a chance at getting in. The press coverage was relentless, some of the leading players no longer left through the stage door after performances but were hustled out some subterranean passage to avoid the crush of fans seeking selfies and autographs, and on and on.

The frenzy has ended. It’s still the toughest ticket in town, but secondary market prices have dropped (a little). Most of the original leading cast members have moved on to other projects. The final Ham4Ham show was the Wednesday before Labor Day. Hamilton is on its way to its second life as a touring staple and a Broadway stalwart, running for so many years that, eventually, there will be cast members who saw it when they were 12, decided that their life goal was to be good enough to be on that stage when they were in their 20s and made it there.

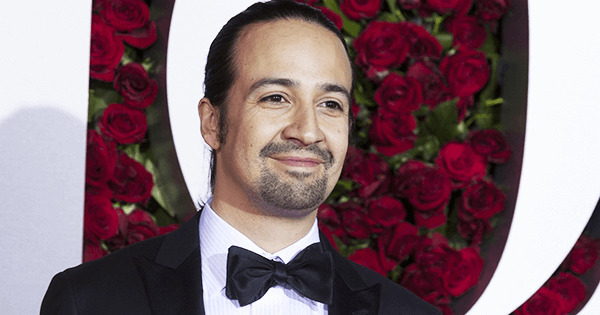

For now, let’s return to the Richard Rodgers in June: This school’s-out crowd had a post boy-band concert vibe: predominantly white, a lot of tweens, teens and women in their early 20s (though they were not the only people there by any means, just the loudest). Around 12:30, Lin-Manuel Miranda, who wrote the music, the lyrics, the book for the show, and at the time was its leading man, emerged through the doors in front of the theater, wearing jeans and a faded gray T-shirt that read “Hunter Football,” his shoulder-length hair in two tousled Princess Leia-ish buns. (An aside about that hair: silky and jet black, it was something of a sacred object to many fans. When he got a haircut following his final performance and tweeted a picture of the shorn locks, the outcry nearly broke the Internet.) He’s slight-framed and not very tall. You can imagine him as the sweet, smart nerd in the back of the classroom whom everyone likes but who doesn’t exactly run things. But that was then. He’s sure as hell running things now. At the sight of him, the girls started screaming. They screamed like he was Elvis Presley. They screamed like he was Paul McCartney. They screamed like he was Justin Bieber. They screamed for this 36-year-old Manhattan-born, bilingual Puerto Rican the way girls have always screamed for some lovely man on stage. But this time the man isn’t white. Not only does he not obscure or ignore his ethnicity, but he insists on multiracial casting for this show, now and forever. This time they’re screaming for someone who is not only a performer but also the creator (in collaboration with a host of other remarkable theater artists) of a musical that has audiences humming along as they reconsider exactly who founded these United States.

To my mind, the adoration of Lin-Manuel that has grown within the church of Hamilton takes the meaning of this particular type of fandom to a different, intriguing place. Sure, folks have adored black and Latino actors and singers before—but never has someone who’s become a scream-worthy pop idol found his devotees via a complex, innovative work of theater. The young women and girls screaming for Miranda on West 46th Street have seen a black man in the White House for most of their lives. But that’s political power. Miranda and the musical he created have a hold over the emotions of these women and girls (and thousands of fans of every gender, race, and age) in a way that—as near as I can tell as an old hand at deep-rooted, formative, and meaningful celebrity crushes—has not been widely seen before for an artist of his caliber. At a moment of so much anti-immigrant sentiment, a moment when a demagogue who exploits racist fears stands a very real chance of being elected president, what does it mean that an omnipresent object of fan adoration is a supremely talented man whose work isn’t disposable and who isn’t white?

The Hamilton ticket lottery was initially meant to be a lottery like any other—you’d throw your name into a hat and if you won, pay a nominal price for the prize. Here, the price was $10 and the lottery was given a name. A Hamilton for Hamilton, get it? At the first Broadway preview, about 700 people came to the Richard Rodgers Theatre to enter the lottery, so many that Miranda was moved to come out and thank them. The next day, again a large crowd. This time he and Jonathan Groff (who played King George) came out onto the little steps in front of the theater and rapped for a minute, using bullhorns. It grew from there. At first, the performances were haphazard but grew increasingly organized and star-studded, though never longer than five minutes or so. It got so popular that they had to limit the live performances to once a week, for Wednesday matinees. During the winter, Miranda came up with what he called Digital Ham4Ham, video performances that were posted to YouTube every Wednesday. In the spring, it was back to the live shows, which were also recorded and posted on YouTube, and have been viewed millions of times in aggregate.

By the time I attended, the audience in front of the theater routinely numbered in the low thousands. A couple of jovial cops and barricades kept us on the sidewalk so we wouldn’t get run over. Many people, like me, were there just to see what Ham4Ham would bring that day, not to enter the lottery. I caught one of the last ones Miranda hosted. I didn’t go as a sociologist or writer; I was there as a fan.

I had seen Hamilton with my husband, son, and daughter on February 25, 2016—a day I’ll always remember. We paid more than we’d ever paid to go to a Broadway show before, wanting to see this piece of theater history and have a significant family outing before my daughter left for college in the fall. I expected something big: no one, it seems, has a neutral response to Hamilton. Most people have a great time—but some, like me, are staggered. I came out of the theater uplifted, thrilled, dazzled, grateful, soul-shifted. I had expected to be very emotional—crying, deeply moved, that kind of thing. And perhaps I will be the next time I see it. But the first time (and there’s nothing like your first time, is there?), it was too overwhelming for tears. It was like riding a rocket. It was like surfing a wave. It was like … insert simile here that describes enormous force and enormous pleasure. It was like that.

And that’s where it all began. At this writing, I’ve listened to some portion of the cast recording every single day since that February night. Like thousands of other people, I’ve spent a lot of time hanging out with the YouTube/Twitter/Internet version of Miranda. There is a huge amount to hang out with. While his skill with the quill is undeniable, so is his skill at navigating and placing himself in the image-soaked world we live in. I have lyrics to various Hamilton tunes in my mind 24/7—when I wake up in the morning, they’re just there. I’ve got it bad. And that’s good.

Hamilton came to me at a time when I was despairing about my life as a writer, as an artist. I’d been stuck on a novel for four years, stalling and starting, avoiding, beating myself up. Finally, I set it aside, uncertain what to do. When I saw Hamilton, I hadn’t written anything for months. I wondered, after having published four novels, if I had anything left. Maybe I’d said all I had to say. This made me sad, but it seemed possible.

So I saw Hamilton while I was stuck, and then I was in love with it and then, as I spent more time with it, the musical kicked open the door—or rather, it helped me kick open the door. By July, I had been thinking about aspects of Hamilton and Miranda for months. One fine day, all of a sudden, a paragraph came to me, and then another and another—the first draft of this essay was written in a matter of hours. It was the first time in years I’d written anything with joy and enthusiasm. It was like something out of a movie. But, as any writer will tell you, a rush of inspiration like that is a miracle—a miracle that can’t be summoned, a miracle that rarely happens. A miracle that one artist can sometimes give another, even if they never meet. Like others have said—sometimes glibly, sometimes sincerely—Hamilton changed my life.

At first I was devoted to the show itself, not so much to Lin (that’s what his friends call him). First the constant listening to the cast album, learning its rhythms and depths, then the babbling about it to ever-less-interested friends (and family; after the excitement of show night, it became clear that although they had enjoyed themselves, I alone was possessed), and then the obsessive posting and reposting of articles and videos on Facebook. Then I started watching YouTube—getting interested in Miranda’s pretty black hair, being impressed by his freestyling skills, thinking how charming it was that he was so easily moved by the artistry of his fellow performers at the Ham4Ham shows. But then came the video that pushed me over the edge: the digital Ham4Ham in which he sings “What You Own” from Rent with Adam Pascal of the original cast. It’s shot in a tiny room (backstage somewhere?) with a piano and a sofa wedged into it. Miranda is perched on the arm of the sofa and as he harmonizes with his idol, he looks more and more like he just might tip over from excitement. As they finish the song, he finally does collapse next to Pascal, laughing and clapping his hands. All four men in the video (Pascal, Miranda, guitarist Kenny Brescia, and Hamilton musical director Alex Lacamoire) share such an earnest musical-theater-geeks-in-their-dorm-room lack of self-consciousness that I just couldn’t fight it any more. I was in love.

Love may seem a peculiar word to use here. I mean it’s not like I know the man at all. But I know the feeling. When I was 15, I fell in love with Mikhail Baryshnikov, the greatest ballet dancer of the late-20th century—an affection that came as a complete surprise. I had never taken a ballet class, had no pointe shoes hidden in my closet, had no ballet fans in my family. Though I’d been to modern dance performances, I’m not sure I’d even seen a ballet before his 1974 defection from the Soviet Union to the United States. I can’t remember when I first became aware of him. These days it’s hard to imagine a ballet dancer being a pop culture fixture, but back then he was as omnipresent as Miranda. I read ballet books voraciously and bought every photo-packed coffee-table tome he was in. I started studying ballet myself, but didn’t get very far. I was 15; it was too late for me to develop turnout, the strength for pointe work, the narrow, breastless body of a dancer. But I tried for a while, at one point taking 10 classes a week. Baryshnikov was one of the stars of the 1977 ballet-based movie The Turning Point, so I saw it at least 20 times.

He was born in Latvia; I was born in Cleveland. He’s 12 years my senior. He’s white; I’m black. I didn’t ever see him perform. None of this mattered in my emotional relationship to his public persona. I use the word persona because, as is obvious in this kind of love, the man I conjured is not Mikhail Baryshnikov. We don’t know these guys—we just feel as if we do, as if we must. When you are 14, 15, 16, the man you carry in your mind is real, even though he’s not in your real life.

But it affected my real life. My love for Misha (that’s what his friends call him) helped lead me on a path out of my life in Cleveland in a completely unexpected way, a way that was solely my own. A path he influences to this day—my first novel, Another Way to Dance, my subscription to New York City Ballet, the novel I set aside that I might get back to, my love of this esoteric but so, so gorgeous art form. Without him, I don’t know if I’d even have been a writer. He showed me something else. He pushed me toward my own dreamworld.

There is also the fact of race in my love for him. Ballet has a long history of racism—of assumptions about body types, of who can dance it “correctly” and who can’t. I became well aware of this as I learned about the form. But I couldn’t not love it. I couldn’t not love him. So I had to think my way through the bias. I had to think—or rather feel—my way to how I would love something where there weren’t many people like me on the stage or in the audience. I had to learn not to give it up, to have the strength to hang onto what it gave me, even across that racial divide.

Miranda’s gift is as dazzling as Baryshnikov’s. But unlike Baryshnikov, who danced for us but didn’t talk to us much, Miranda’s engagement with his audience is enveloping, enthusiastic, and generous. What he gives, nonstop, is an invitation to share his love of, well, the whole world. There’s a meme that reads, “Find someone who looks at you the way that Lin-Manuel Miranda looks at literally everyone.” As near as we out here in the dark can tell, he regards just about everything with an entirely open heart and with a nearly unwavering focus. It’s as if he wants to know everything, hear everything, talk to you about everything. In the photos in this meme, no matter who he’s looking at, he’s looking at them, almost into them, lovingly. No matter what he’s listening to, he’s listening to it; the music that influences Hamilton is everything from ’90S R&B to Rodgers and Hammerstein to hip-hop from its creation the present day, and so much more. He shows up for all of life. And he wants us to do it too. For years he’s exhorted his nearly 800,000 Twitter followers to do just that, morning and evening, almost every day. An example:

“Gmorning. You can fume at the world if you like. You can also use your words, art & gifts to let us in. Build us a bridge to where you are.”

He is sure of the power of love, the power of language, and the power of art. He wants you to be sure of it too.

It isn’t just talk. He’s taken real-world measures to improve lives in arenas he cares about. He and the show’s producers worked with the Gilder Lehrman Institute to develop a curriculum about the Revolution that uses Hamilton as a teaching tool. With the help of the Rockefeller Foundation, 20,000 New York City public school students (from schools with a high proportion of students receiving free lunch) have seen or will see the show for $10 apiece, with a chance to interact with the cast, write their own history-based raps, and read The Federalist Papers. There are plans to offer the same program in public schools in other cities where the show will be produced. He leapt immediately into fundraising to aid the families of the victims of the Orlando shooting, nearly all of whom were gay Latino men. Like the real Hamilton, Miranda has written his way into a position of influence, which he’s used in the service of people who are often overlooked.

And you’re unlikely to ever find another teen idol who asks his audience to consider that death is coming for us all, sooner or later. Speaking at a summer program for theater teachers, he said,

Charge your kids with that, the notion that life’s a gift, it’s not to be taken for granted, it’s not to be taken lightly. You’re born with gifts and you’re born with an honesty that can never really leave you. What are you going to do with your time? What are you going to do with your time on this earth?

I remember being a teenager and thinking, ‘We have so much time, we have time to kill.’ Man, what I would do to get that time back. I think the continuing awareness that being here is a real gift, that whatever is happening in the world, make the most of it and sink your teeth into whatever you’re doing. That’s your biggest charge and the rest flows from there.

That charge is an explicit theme of Hamilton (“Why do you write like you’re running out of time?”), something the work forces you to consider. Imagine taking this idea in when you are 14, 15,16. It would knock you out. You’d fall apart.

Through his every act as a public figure, Miranda reminds us of the full humanity of people of color, all the ways we contribute, all the ways we are and all the ways we matter. Through his work (both Hamilton and his first musical, In the Heights, which was inspired by the Latino community in Washington Heights where he was raised and still lives), he joyously reminds audiences that we helped build this nation, that we belong here and whether you like it or not, we’re staking our claim. We must be acknowledged. We will be acknowledged. The young fans are taking that in too.

There are a lot of comments under the many YouTube videos in which Miranda appears, about how “adorable” he is, what a “cinnamon roll” he is-the sort of declarations of affection more commonly made about a stuffed animal, or a child. But Hamilton is very much the work of a grown man—epic, authoritative, and frankly, kind of sexy. So’s the guy who wrote it, not because of what he looks like, but because of what he thinks like. Both as performer and writer, Miranda knows exactly how to take pleasure in every moment—and how to give it as well. You can hear it in the flirtatious snap of Hamilton’s dialogue with Angelica Schuyler in “Satisfied” and in his drawn-out moans of “yes” to Maria Reynolds in Hamilton’s cheating-heart song, “Say No to This.”

An example of the attractiveness of his mind at work is a 2014 performance with Freestyle Love Supreme (a rap group he helped start pre-Hamilton) that I found in my Miranda-related YouTube peregrinations. It’s about making a mixtape for a girl, mourning that long-gone, oh-so-romantic technology. In it, he looks directly into the camera, extends his hand toward you, and speaks with such intensity (and a pretty slick double entendre that he made up on the spot)—“Yeah, I’m’a give you good and plenty / I don’t need the 60, I need the 120 / of that Maxell cassette and oh please believe it / I’ll start it uptempo so we can achieve it”—that you just know he’s making that mixtape for you. This guy is not a stuffed animal. He’s thinking fast and paying exquisite attention. And he’s gonna make you feel really good.

Hamilton makes you feel good using the same extraordinary verbal dexterity and attention to detail. In performance, the staging and choreography turn up the thrill-o-meter even more. The opening number, “Alexander Hamilton,” begins with a black man standing alone on stage, wearing a simulacrum of 18th century dress. He begins to tell us a story, handing the phrases of the tale off to first one, then two, then three, then four men, all black or Latino, emerging onto the stage one by one, moving back and forth through the spotlight. We then meet Alexander Hamilton, also Latino, alone, also framed by a spotlight, declaring his name so firmly that we dare not challenge him. These guys are in charge—we have to go with them. The power residing in this image—all these beautiful young men with their beautiful shades of brown commanding the stage—is unprecedented in a Broadway musical.

You don’t have to see the show to hear the strength inherent in so fluently and unapologetically using an assertively masculine idiom created by African-Americans. The cast recording conveys the same fiery energy. Miranda, in taking hip-hop prosody and shaping it to the conventions of musical theater, has offered audiences (both young and old) a new understanding of the possibilities of this language.

The versatility of the language sinks into the ear over time, as do the many layers of the lyrics themselves. Somewhere around the millionth time I listened to these lines in “My Shot”: “Rise up! / When you’re living on your knees, / You rise up. / Tell your brother that he’s gotta rise up. / Tell your sister that she’s gotta rise up” I realized that they weren’t lines that only applied to the 13 colonies. They might well be addressed to brothers and sisters—young black and brown men and women—listening right now, living right now.

So the show takes a stand, and makes you laugh and turns you on. Offstage, there is a different aspect of Miranda’s personality that invites the love his fans feel: he cries, like, all the time. He cries about good things like the gorgeousness of performances by other actors and singers he admires, at reading aloud from the Ron Chernow biography that inspired the musical, at having a dream come true when he gets a small part in Les Misérables on his day off. And he cries about horrible things like the Orlando massacre, which happened early in the morning on the day of the Tony Awards. That night, when he won the award for Best Original Score, rather than pulling a brief list of thank-you’s from the pocket of his tux, he wept openly as he read a sonnet he had written acknowledging the horror and celebrating love.

The poem and his heartbroken reading of it demonstrate a different aspect of masculinity than the one seen in Hamilton’s opening. Being strong and being gentle and open to experience do not cancel each other out. Being angered to the point of tears by atrocity and responding with art doesn’t make you less of a man. That’s a hell of a message for a young person, male or female, to get. And to see this kind of emotion coming from a man of color—whose roles are so narrowly defined in our culture and who are so rarely seen as gentle or sensitive or smart—well, it’s gonna leave a mark.

Falling truly, madly, deeply in love with the image and the work of both Mikhail Baryshnikov and Lin-Manuel Miranda has inspired me, taught me, woken me up. It was dizzying and intense to a teenager and no less so (though more surprising) in middle age. That’s why I know what I know: Those screaming girls and the 10-year-old boys who can sing and rap along with the whole two and a half hour cast album are truly, madly, deeply in love, too. As they pay attention to the music, the message and the man himself, they are learning and being inspired and pushed to grow in some ways they recognize now and in some ways they won’t recognize until they are older. Where will this passion take them? No way to know now. But if my experience is any guide, it will hold many blessings. Love has a way of doing that.

When I think of the cast of Hamilton, I think of Spike Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It and the black filmmakers (and others who work in the industry) who followed through the doors he shouldered his way through. I think of The Cosby Show which, despite Cosby’s dark hidden life, helped pave the road that led Barack Obama to the White House. I think of the fact that those in the audience are not the only ones being inspired. In the book Hamilton: The Revolution (which contains the libretto and extensive commentary about the making of the show), Okieriete Onaodowan, who played Revolutionary War spy Hercules Mulligan in the first act and James Madison in the second, says how sick he is of playing a “messed-up black kid.” And how happy playing James Madison made him: “I’m a black man playing a wise, smart, distinguished future president.” In the same book, Daveed Diggs says that seeing a black man playing a founding father when he was a kid would have meant a great deal to him: “A whole lot of things I just never thought were for me would have seemed possible.” He adds, “I always felt at odds with this country. You can only get pulled over by the police for no reason so many times before you say, ‘Fuck this.’” The man who said this won a Tony Award for his performance in the dual roles of the Marquis de Lafayette and Thomas Jefferson. That won’t keep him from getting pulled over, but it matters. Representation doesn’t mean everything. But it does mean something.

Not long ago, I met a 93-year-old black woman who said this when asked about the grim state of race relations in the United States: “I’ve seen an awful lot. Change is evolutionary, not revolutionary.”

We live in a confusing time when it comes to culture and race. Black men and women are shot with horrific frequency by police officers and a new civil rights movement has sprung up in response. Economic inequality is at an all-time high, with African Americans and Latinos near the bottom by almost all markers. The invective at a Trump rally or on Fox News is terrifying in its stark, unrelenting racist and anti-immigrant rhetoric.

At the same time, works of art and works of thought that challenge the status quo about how black people and immigrants live in and are accepted by this country (sometimes with humor and a light touch, sometimes with utter seriousness) are numerous and are succeeding, often hugely. There’s Ta-Nehisi Coates’ steely, and best-selling, indictment of white privilege and racism, Between the World and Me. There’s the sitcom Black-ish, which is downright hilarious—and had an episode dealing with police brutality. There’s the work of visual artists like Simone Leigh and Kehinde Wiley, subverting and questioning tropes of white dominance in art.

Hamilton stands tall within this exciting cultural moment. It is striking that a musical that reimagines the founding fathers (and mothers) of the United States as people of color has arrived to this much acclaim at a time when the country is undergoing an inexorable, fundamental change.

According to the U.S. Census, white people overall will be a minority in this country by year 2044; white people under 18 will be in the minority by 2020. While racism and xenophobia are part of the DNA of the United States and unlikely ever to leave us entirely, perhaps today’s particular manifestations of hatred are the frantic death throes of white dominance and the birth of a different nation. In her essay in The Los Angeles Review of Books, “The Ecstatic Experience: Hamilton, Hair and Oklahoma,” Laurie Winer considers the particular strength of the form of musical comedy itself as a way to wrestle with notions of what it is to be American and speculates that part of Hamilton’s vitality and timeliness comes from its awareness of and enthusiastic embrace of our transition to a primarily multiracial nation.

She writes: “No essay, no treatise, no satire can alter brain chemistry in the way that this kind of musical theater experience does. As Oscar Hammerstein might say, believing in, or being transported to another world, is the first step to realizing that new world.”

As an object of fandom, Miranda and his musical stand at the edge of this hoped-for new world, reflecting the possibilities that might lie ahead should the better angels of our nature triumph. We stand at a moment so rife with horrors it can be hard to believe that they will. A musical will not save us. A musical can’t undo evil and terror and racism and atrocity. And I in no way want to sound naïve or minimize or gloss over that evil and terror and racism and atrocity. And yet. Change is evolutionary, not revolutionary.

For a lot of teenage girls to adore a Nuyorican guy and the multiracial cast of his musical offers a new vision of who is valued, who is worthy of idolatry. For thousands of young people to take into their bones a work of art that raises provocative questions of race and ownership and power in the founding of our country may change how those bones are formed. The inner lives of those young people are being shaped by a man who is woke, and whose work presents the possibility, the suggestion, that they get woke too.

In the epilogue of another masterpiece of American theater, Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, Part Two: Perestroika, the character Prior Walter says, “We won’t die secret deaths anymore. The world only spins forward. We will be citizens. The time has come.” With my shrieking new friends in front of the Richard Rodgers Theatre on that summer day, I found myself hoping that all of this screaming and all of this love—this love I know so well—was a small spin forward. Back in 1980, the now largely forgotten band The Knack had an album entitled “… But the Little Girls Understand.” Perhaps they do.