I’ve been married twice, but have only had to deal with one father-in-law. In my first marriage, undertaken when I was 20, Carol had a very strong if ambivalent connection to her father, Paul, who was a Viennese psychoanalyst. My present wife, Cheryl, was unfortunate in that her father, once he’d divorced her mother, disappeared from his daughter’s life; but that meant by the time I met her and proposed, I did not have to live up to another father-in-law’s stringent standards.

Paul was a romantic figure—or at least his daughter romanticized him, as did I. He had escaped the Nazis by fleeing Austria when he saw soldiers with swastikas in front of his building. A Jewish graduate student in German literature, he left behind the love of his life. In a displaced persons camp he met Ellen, the woman who would become his wife: not that he had the same strong feelings for her, but she was a decent, sensible woman who adored him and she would do. They came to the United States, where his sponsor convinced him to switch professions, and he went into training as a psychoanalyst in Topeka, Kansas. The family—which by now included two daughters, Carol and her younger sister, Barbara—moved to Bethesda, Maryland, just outside Washington, D.C., when he was offered a job at the National Institute of Mental Health. There he engaged in research while seeing private patients in his suburban home.

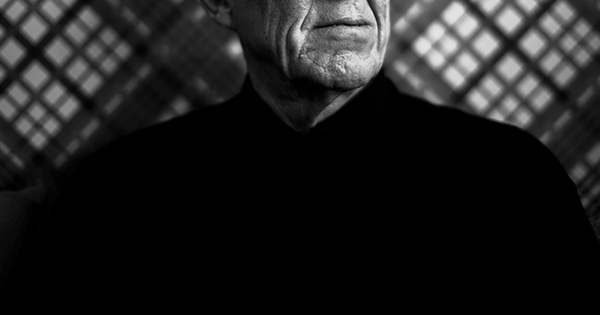

The whole family had accustomed itself to being silent while he was seeing patients. Some of that silence persisted even after the patients had gone; I got the feeling that everything in the household revolved around this melancholy man’s taciturn moods. He seemed to me almost a parody of the German intellectual: pipe-smoking, listening to the classical music station, picking up and reading a professional journal by his armchair, only to lay it down irritably for one of several books on the coffee table; he was a little stiff in his manner, not a chatterbox, and you had to instigate the conversation each time and hope to engage him. I learned through others that he was something of an eclectic freethinker when it came to psychotherapeutic practice, and I would have liked to quiz him about his departure from standard Freudianism, but he was not forthcoming on professional matters. I sensed he regarded native-born Americans as childish, naïve, and intellectually primitive. He also had, like Theodor Adorno, that European snobbishness toward American popular culture, and grumbled about the poor quality of American baked goods. I was fascinated by him, as if I were encountering one of Thomas Mann’s characters in real life. Though I mocked him behind his back, I wanted desperately his approval. That was not to be: he was one of those people who draws others to him by withholding his approval, just a little, just enough to keep you believing it might be possible.

His daughter Barbara resisted his somber air and clowned around; he loved her mischievous sassiness, craved its lightness. But Carol was more the thoughtful, sad type, like him: she kept getting pulled into his dark, heavy orbit, hoping for his approval by shining academically. When she was a teenager, he had used her at times as his library assistant, fetching books. Precisely because he identified with her, he worried that she was in for a troubled life. He had a way of making her doubt herself. Then she met me and started to break away from his influence. I encouraged her to rebel against him. We were enacting that typical pattern of a first love that allows two young people to distance themselves from their parents.

But I myself was drawn to him—physically, even more than mentally. He was a good-looking man with a masculine, character-filled face, full head of hair, big shoulders and strong hands, and he liked to wear plaid woolen shirts. He had that typically Tyrolean appetite for hiking, the mountains, and the outdoors. The family always took camping vacations, something I never did when I was growing up. I came from a Brooklyn slum, more like a ghetto, and I think he was put off both by my working class manner and my obvious Jewishness. A secular humanist, he downplayed his religion all the way—the kind of Jew who tells his children once and only once that they are Jewish so that they will know in case the Gestapo comes again.

As for the whole bourgeois suburban setup, so foreign to me, I was both enchanted and repelled by it. The house had so many rooms that everyone was always going off into their own sanctuary; it was too quiet, too lonely. I did like the comfortable couch, the spacious living room, the back yard whose trees concealed next-door neighbors from view. But my impulse was to hide in the basement, which I did for part of my wedding party.

Shortly after the ceremony, Paul took me by the arm and said: “I know you want to be a writer. In every century there are maybe three writers who count. In the 19th century, it was Goethe, Balzac, and Tolstoy. In the 20th century, Proust, Joyce, maybe Kafka or Rilke. If it doesn’t work out, you can always do something with television. I have complete faith in you.” Meaning, he had faith that I would give up this impractical dream and decide to make money. I think he saw me (quite rightly, it turned out) as an unreliable provider. At the time I was very offended. Now that I’m the father of a young woman who is dating boys I find lacking in maturity, I understand why he had worried about this unshaven wannabe writer’s ability to take care of his daughter. He kept inquiring whether we were planning to get health insurance. At 21, who bothers about health insurance? Ridiculous, right? Now I know better.

Surely there was some competitiveness between us over the writing game. He had been a student of literature, after all. His letters to his daughter were filled with quotes from Goethe, Schiller, Hölderlin, and Novalis. He had precise handwriting, he used a fountain pen with light green ink, and there would always be indented lines of poetry, half a stanza, let’s say, in German. I would get Carol to translate them for me, then I would make fun of him: it seemed so pompous to write your daughter that way, with little wisdom nuggets from classical German poets. Still, the fact that he had committed all these poems to memory was impressive, I had to admit.

In one of his letters he said with a sigh that he always spent an hour every day reading literature, and often he was disappointed. I thought this was the most preposterous, asinine thing I had ever heard. Who was he to be disappointed in literature? I worshipped at the shrine of literature; it could never fail me. I mean, I understand now that he saw patients during the day, and at night, tired, he would pick up a novel or a book of poetry and … well, okay, he was disappointed, I get it. He had a right to be disappointed. But we were coming from such different places. One time he was reading James Baldwin’s Another Country, that season’s most-praised novel. He picked up the book and said solemnly: “This man has known suffering.” I wanted to laugh out loud. From my sampling of the book, I thought Another Country was corny and contrived—still do, in fact. I love Baldwin’s essays, but not his novels. Regardless: it was Paul’s willingness to be so touched by this black American writer (overcoming his customary disdain for his adopted country’s culture) that resonated in me long after. At the time, though, I was the sworn enemy of solemnity.

A few years later, Carol and I were at a film festival in Montreal when we received a phone message: Paul had died of a massive heart attack on a camping trip. We rushed to the burial. Not long after, our marriage broke up. Perhaps my father-in-law had been keeping us together all this time by the force of his disapproval.