A slaveholder wrote the Declaration of Independence and a man who believed in black inferiority later transformed the ideas it laid out into universal gospel. Thomas Jefferson and Abraham Lincoln were men of their times, of course, times in which the idea of white supremacy was far more prevalent than in the 21st century. Or so it seemed.

White supremacy is more visible and vocal than it has been in decades. Its reemergence can be traced to several developments: a reaction against the Black Lives Matter movement that began in 2013, the massacre of black worshippers at the Emanuel AME Church in Charleston in 2015 that led to a reexamination of the meaning of Confederate symbols, and the election of Donald Trump in 2016. These issues fused tragically in Charlottesville on August 12.

Unfortunately, many Americans fail to realize that white supremacy is not an aberration in this country but for most of its history the norm, forced into retreat only by the actions of those who struggle to make liberty and equality, not slavery and racism, the polestars that guide the nation.

My guess is that Jefferson would have been appalled by the events at the University of Virginia, which he considered one of his greatest achievements along with the Virginia Statute of Religious Freedom and the Declaration of Independence. Those accomplishments alone grace the monument above his grave.

But Jefferson, like many Americans in his time, never shed his belief in black inferiority. Blacks, he thought, were incapable of self-governance, “as incapable as children of taking care of themselves” and free blacks were “pests in society.” He feared servile insurrection and believed the only solution to the problem of race was to remove free blacks from the United States, “beyond the reach of mixture.” Jefferson recognized that slavery as an institution was “a hideous blot,” but he never emancipated his slaves, except for relatives of Sally Hemings with whom he fathered children, and he showed few qualms about breaking up families and selling off slaves to reduce his indebtedness.

It took Lincoln to salvage the Jefferson we desire from the one who lived. Lincoln grounded his understanding of the nation on the Declaration of Independence and argued time and again that the phrase all men are created equal included blacks. “All honor to Jefferson,” proclaimed Lincoln. The Declaration “set up a standard maxim for free society . . . constantly looked to, constantly labored for, and even though never perfectly attained, constantly approximated and thereby constantly spreading and deepening its influence, and augmenting the happiness and value of life to all people, of all colors, everywhere.”

Lincoln embraced gradual, deliberate change and exemplified that approach. He too had believed in white superiority: “I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races. … There is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together.” Lincoln supported colonization, though he realized it was not possible on a large scale. He always hated slavery, but as president refused at first to act against the institution or make provisions for whites and blacks to live peacefully in freedom.

The Civil War compelled Lincoln to bring Jefferson’s maxim of a free society to fruition. We can watch him change his mind over time. He moved from saying he could not attack slavery where it existed to freeing slaves in Confederate areas not under Union control, and then advocating for a 13th Amendment abolishing it throughout the United States; he shifted from embracing colonization to authorizing the enlistment of black soldiers; he stopped believing that blacks could not attain political equality and, in the last speech he ever gave, publicly endorsed black suffrage. Thinking about Lincoln, civil rights activist and historian W. E. B. Du Bois exclaimed, “I love him not because he was perfect but because he was not and yet triumphed.”

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Southern states began erecting monuments to the leaders and events of the Confederacy. Many of them went up decades after the war, well into the 20th century. Try as some Southerners might to claim that the statues merely celebrated Confederate heritage and the principles of duty and honor, that heritage is inseparable from support for white supremacy. Alexander Stephens, vice president of the Confederacy, declared that the cornerstone of the Confederacy “rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.” The Southern Poverty Law Center has documented more than 1,500 public symbols of white supremacy in the former Confederacy. And not only there: a statue of Alexander Stephens is displayed in the U.S. Capitol, along with fellow Confederates Jefferson Davis and Robert E. Lee.

Some of those memorials, such as the recently removed Liberty Monument in New Orleans, honored violent white supremacist groups such as the White League, which sought in 1874 to take control of the state government. In explaining its removal and that of various statues to Confederate leaders, Mayor Mitch Landrieu said, “These statues are not just stone and metal. They are not just innocent remembrances of a benign history. These monuments purposefully celebrate a fictional, sanitized Confederacy; ignoring the death, ignoring the enslavement, and the terror that it actually stood for.”

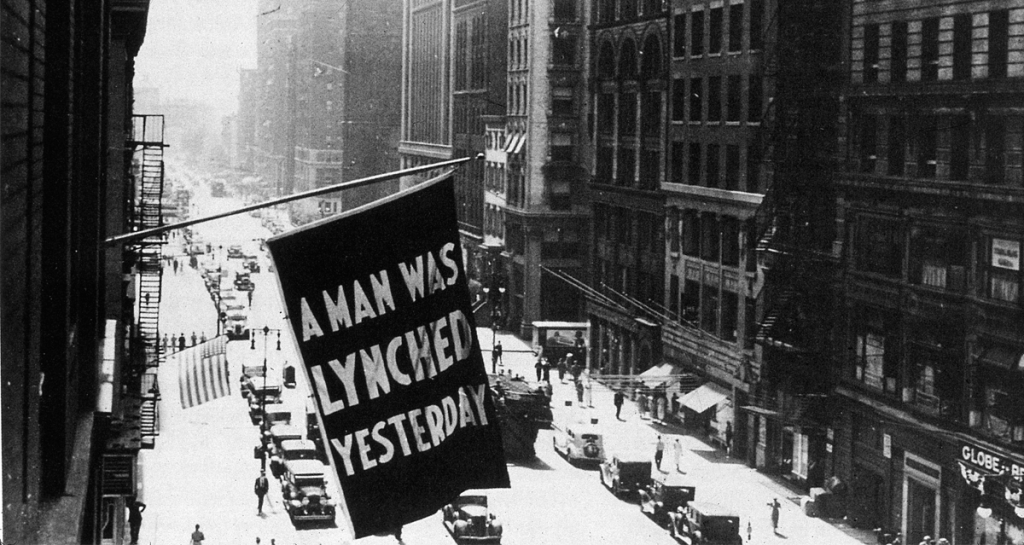

Those memorials were meant to send a message to the black population. In case they did not receive it, in the decades following the Civil War and reaching well into the 20th century, white supremacists lynched thousands of free blacks. In the 1920s and 1930s, Du Bois, who served as director of publicity and research for the NAACP, flew a flag from its Fifth Avenue offices that read “A Man Was Lynched Yesterday.” There are many aspects of American history that are inexplicable and unconscionable, perhaps none more so than the failure of Congress to pass antilynching legislation in the 20th century. In 2005, the Senate formally apologized for not acting.

In the aftermath of the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s, many Americans believed that Jefferson’s maxim had at last become policy. Legal segregation had been defeated. Equal rights had been recognized. White supremacy had been forced into the shadows. But it seems it hasn’t taken much for an assault on people of color and the erosion of the principles of the Declaration of Independence to begin again.

So it is time to renew the battle, to continue the struggle. White nationalists can’t be convinced, but perhaps white moderates can. This was the thrust of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Letter from Birmingham Jail in 1963. Religious leaders must step forward. Moderates must take a stand. White supremacists, and the politicians who support them, will be defeated only by those willing to continue to fight for what King called “the sacred heritage of our nation,” a heritage not of hate but of hope.