The Wine Lover’s Daughter: A Memoir by Anne Fadiman; Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 272 pp.; $25

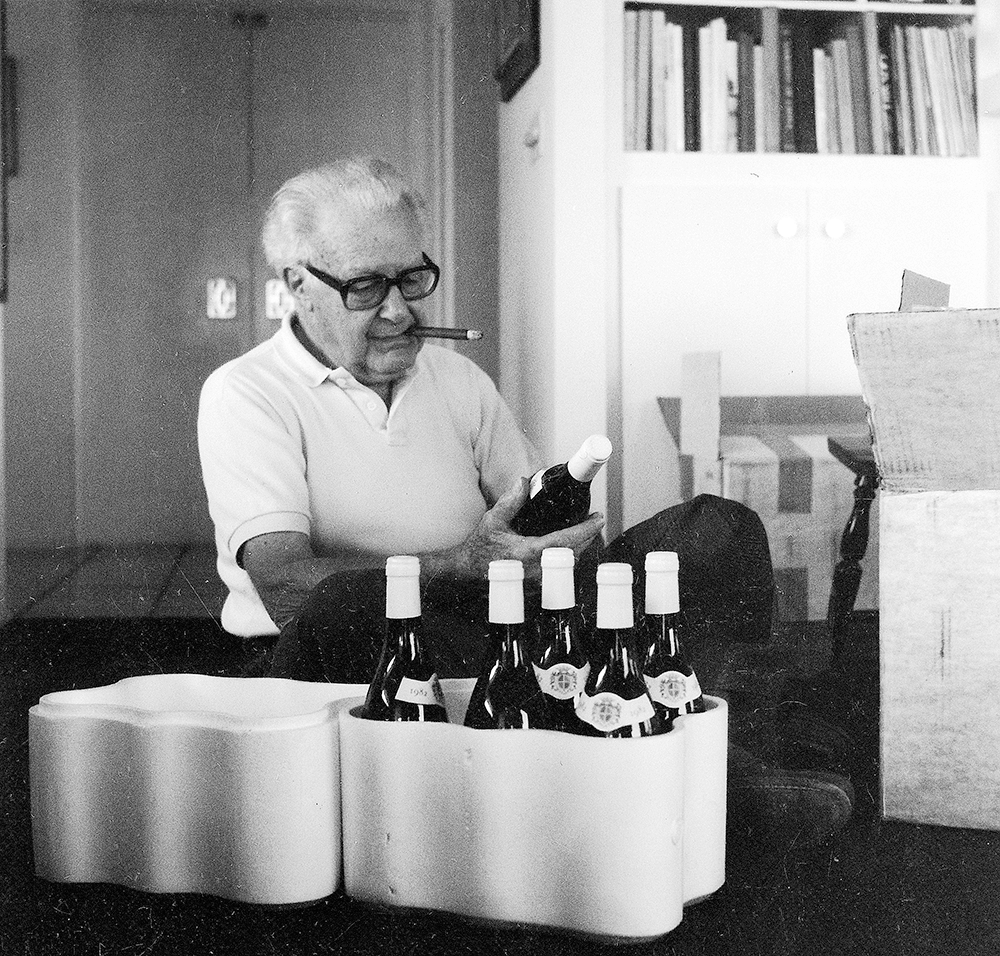

Clifton Fadiman was a foremost example of what has become an endangered species—the American public intellectual. Erudite and blessed with a prodigious memory, he cultivated a patrician sensibility. As the host of the popular radio program, Information Please, and then a series of television shows, he played with aplomb the role of an elegant, well-bred raconteur, always ready with the seemingly perfect quip or bon mot. Fadiman published a score of anthologies and editions, and his many jobs included serving as the book review editor for The New Yorker and helping establish the Book-of-the-Month-Club (followed by a 50-year stint on its editorial board). As his daughter, Anne, herself an essayist and a former editor of the SCHOLAR, writes in this memoir of her life with him, “he was witty, charming, and never, ever vulgar.” In public and apparently in private too, he exuded class, an integral element of which was a quite open love affair with fine wine.

In the 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s, when Fadiman was at the height of his renown, few Americans cared about wine. That would change in the decades to come, but back then wine remained reserved primarily for those who had grown up with it on their family dinner tables—immigrants to be sure, but more to the point, people who felt at home at cotillions or country clubs, and who lived in apartments on Park Avenue or in stately homes in Beacon Hill or on Philadelphia’s Main Line. Fadiman was not one of these. He instead had been born in Brooklyn, the somewhat frail, bookish son of Jewish immigrants who spoke ungrammatical English and whose family belonged, as he later told his daughter, “to the lowest level of the lower middle class.” Even as a boy, he wanted out.

He found escape first through books and then through what books, specifically the great books of western literature, brought him—exposure to a world of upper-class refinement and enlightenment, one that to his impressionable mind was far removed from the ignorant, uncouth Brooklyn of his childhood. This new world was embodied by his blue-blood professors and their wives at Columbia, where he enrolled in 1920 at the age of 16. Fadiman was not the only young, smart Jew there. His circle included Mortimer Adler, Lionel Trilling, and a host of others, all of whom Anne suggests had a choice to make: faced with an intellectual establishment that was almost entirely Anglo-Saxon and Protestant, they could either rebel against it or try to join it. “I don’t think anyone wanted to join more fervently than my father,” she writes. And once he joined, he never left.

To join what he thought of as an elite society, Fadiman had to adopt a persona, a crucial element of which was enjoying wine. Not just any wine, but the best wine, a category that back then included almost only French wines, particularly those from Bordeaux and Burgundy. He insisted that their appreciation was aesthetic as well as physical. He did not drink wine in college or even when first making a Manhattan living of his own. After all, Prohibition was in full jazz age swing, and speakeasies stocked smuggled whiskey and bathtub gin, not grand crus. Fadiman first tasted wine—an inexpensive white Graves—during a trip to Paris in 1927. He adored it, not just the taste, but everything he thought that taste represented—sophistication, elegance, class and charm, exactly the qualities that he wanted for himself. Six years later, after Repeal, he courted this new love with the same ardor that he had devoted to books as a student. He learned all about it, memorizing the 1855 Bordeaux classification and the various vineyards of Burgundy. By then he was starting to make real money, so he also began to collect many of these wines. They, and the cellar book in which he recorded his impressions of them over many decades, provided tangible, sensory proof that he had arrived.

Although certainly extensive, Fadiman’s knowledge of wine, like his knowledge of literature and art, did not much evolve over the succeeding years. Anne notes that he tried more so-called “New World” wines near the end of his life, but just as he displayed no interest in the challenges to the literary canon that arose in the second half of the century, he paid little attention to the challenges to the hierarchy of French taste being mounted by American, Australian, and South American wines during the same period. His understanding of what constitutes great wine was stuck in the past, no matter that a global revolution in both production and consumption was radically changing wine’s cultural role the world over. His love of wine certainly seems to have been genuine, but it also was limited by a preconceived notion of wine’s place in the construction of his own identity. Put another way, his understanding was antiquated from the start.

Fadiman insisted that wine, like great art, was both civilized and civilizing. “[It] forces one to think,” he once wrote. Much as when he chose what to include and what to exclude in his 1960 The Lifetime Reading Plan, he insisted that knowing what to value and why to value it is very different from just knowing what you enjoy. No one, this memoir makes clear, wanted to value wine in that elitist way more than his daughter. She learned about it early on, but the problem came in the simple fact that she never much liked it. “Keep on trying,” her father once told her; wine will seem one day “right and habitual.” That day never came. Anne records devoting considerable effort to trying to change her taste and then to trying to figure out why she kept failing. She sipped wines—all sorts—for decades, but the experiences remained unsatisfactory. She wanted to like them; she wanted to want them. But the only thing wine made her think was that it didn’t taste like her father said it should, meaning that it didn’t inspire or enthrall, let alone civilize. Instead, to her palate, it seemed sour and boring.

Using wine and its appreciation as an elaborate metaphor, this book is ultimately about two people trying to be true to themselves. For one of them, that self is in large measure an invention, modeled on others who inhabited a world he desired. For the other, it is at least in part an inheritance, one she worries she can never quite live up to or equal. But neither of them ever seems completely honest. The father was in many respects a fraud, but the daughter can’t admit as much about him. At the same time, she wants to be like him, no matter that she remains acutely aware of both her own and his inadequacies.

Anne speculates that shortly before his death, her father feared that his life had been an elaborate cover-up concealing the reality of the Brooklyn bookworm who turned his back on some essential part of himself. “But when he drank wine with friends,” she observes, “he always belonged.” At the same time, she admits that as a child of privilege, she needed to embrace, not escape her origins. Her taste, however, betrayed her. No matter how much she may want to, Anne Fadiman will never be a wine lover. As a result, her book is tinged with regret—for what was and what never was, as well as for what is said in its pages and what is not. That a great deal remains unsaid makes The Wine Lover’s Daughter seem incomplete and at times disappointing. But what ultimately redeems this book and makes it worth reading is that it is at heart a story of love. Not the love of books or ideas or even wines, but the love of two fallible people for each other.