The Dawn Watch: Joseph Conrad in a Global World by Maya Jasanoff; Penguin Press, 375 pp., $30

When someone sent me a link to a New York Times essay by Maya Jasanoff recounting her boat trip down the Congo River, copy of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness in hand, my first reaction, I have to admit, was one of weariness: “Oh, that again.”

It wasn’t the most original idea. Norman Sherry, another Conrad biographer, beat Jasanoff to it as early as 1966, and Helen Winternitz wrote the experience up in the ’80s. More recently, there have been macho accounts by Jeffrey Tayler and Phil Harwood, both of whom traveled down the river by canoe. British writer Tim Butcher, in contrast, attempted the journey on motorbike, and alongside all the books, there have been numerous television documentaries and journalistic articles.

Predictably, the essay’s tone got Jasanoff into trouble, triggering a ministorm on social media, angry articles in Quartz and The Washington Post, and letters to the editor complaining about her “Orientalist” and “colonialist” approach. Ever since the Nigerian author Chinua Achebe denounced Conrad as “a thorough-going racist” in the ’70s, any writer referencing Heart of Darkness flirts with danger. That Jasanoff, a Harvard history professor, is herself not white—she describes herself here as “half-Asian” and “half-Jew”—was never going to make a difference.

All of this was a distraction and rather a shame. For while the Congo River journey tops and tails this book, Jasanoff’s gaze extends far beyond that one slim novella (not even among the most popular of Conrad’s books during his own lifetime) and the increasingly stale intellectual debate it has fueled. In Dawn Watch—part biography, part history, part literary critique—she presents Conrad, the Polish exile who became an Englishman because it meant he could go to sea, as one of the first writers to track the process of globalization.

Focusing on four key novels—The Secret Agent, Lord Jim, Heart of Darkness, and Nostromo—she shows how Conrad, publishing between 1900 and 1904, already pinpointed the themes that preoccupy our uneasy times. The ordinary citizen’s panic at the rush of technological innovation (Conrad himself was dismayed by the transition from sail to steam), society’s fears over immigration, the sinister spread of international terrorism, the way corporate capital and government conspire to present the looting of natural resources as philanthropy—all are explored in his work. “For better and for worse,” Jasanoff writes, “Joseph Conrad was one of us: a citizen of a global world.”

Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, as he was christened, was perfectly positioned to chart such tectonic shifts, for he was the ultimate outsider, a melancholy, rootless man flailing in search of safe harbor. The son of two ridiculously idealistic revolutionaries who saw their country swallowed by the Russian Empire’s greedy maw, he experienced internal exile before being orphaned by tuberculosis at the tender age of 11. “Konrad had been adrift his whole life,” writes Jasanoff. “Going to sea just made it official.”

If post-Brexit Britain is turning in on itself, the opposite was true in Conrad’s day. “Freedom turned London into Europe’s beachcomber, collecting refugees washed up by waves of political change,” writes Jasanoff. It was natural to head there. A series of testing merchant navy jobs in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, the China Seas, and central Africa gave Conrad a unique perspective on an era of roiling change, while the tedium of life aboard offered time in which to set things down in the impressionistic, not-particularly-accessible Conradian voice. “Rarely in modern human society are so few people so isolated so regularly for so long,” comments Jasanoff. “Sailors, famously, spin yarns … which—like the lines they coil and mend—come at length, and with twists and turns.”

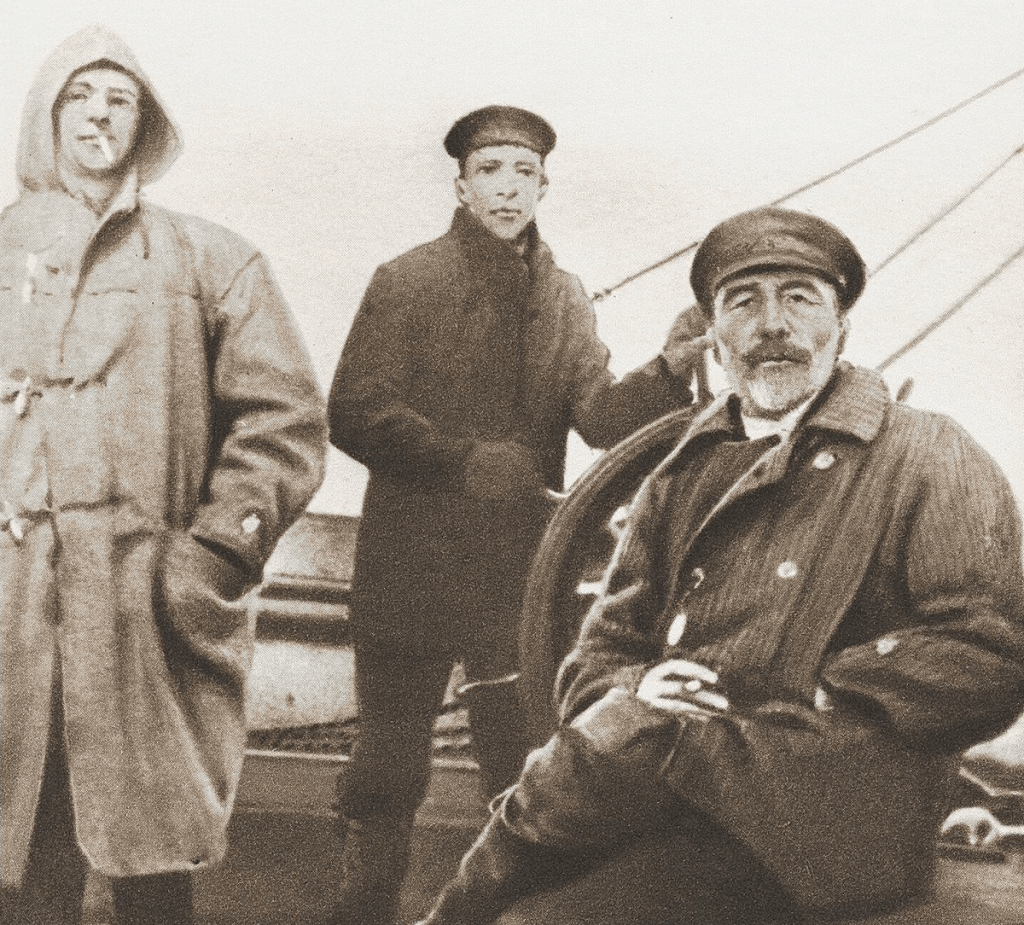

Although Jasanoff relies on previously published work, hers is a fresh take and makes for a rewarding, richly textured read, sprawling in its reach and full of surprising cross-connections. It was good to be reminded, for example, that Conrad, who in photographs appears the archetypal Victorian gentleman—stiff-backed, all whiskers and starched white collar—was actually a contemporary of a young Ho Chi Minh and the lawyer who went on to become Mahatma Gandhi.

Along the way, Jasanoff acknowledges that Conrad rarely showed any interest in or understanding of a woman’s perspective, was casually anti-Semitic in the manner of his day, and took white superiority over “savages,” whether Asian or African, as a given. The same man, according to this account, also probably played a greater role in highlighting the hypocrisy of the West’s so-called civilizing mission and the evils of colonialism than any writer of his epoch. To fail to grasp that both these things can simultaneously be true is to fall into the trap of historical illiteracy.

Historians can be pedestrian stylists. Not so Jasanoff, who shares with her subject the knack of capturing human experience in poetic fistfuls of language, although it’s sometimes hard to know where Conrad’s magic stops and her own starts. Recounting her subject’s voyage up the Congo, she describes how “great black fronts of rain advanced toward the boat, trampled over it like ten thousand jackboots, and marched swiftly away.” I remember being caught by those storms when living in Kinshasa, the Leopoldville of today, and waiting for the weather to tramp on.

She could have gone even further than she does in pointing out the contemporary echoes in Conrad’s work. For any modern resident of Paris, London, Brussels, Nice, or Barcelona, the world of The Secret Agent, with its covert cells, police surveillance, and suicide vests that detonate accidentally, seems very familiar. We are accustomed now to the routine of sirens, public lockdown, Facebook-framed grief, and belated revelations of how a listless young man was radicalized via laptop in a suburban bedroom. Yet Jasanoff skirts shy of any direct reference to ISIS or al-Qaeda.

Conrad would surely have seen plenty of analogies, too, between the cynicism of the “material interests” that shape events in the fictional Latin American country described in Nostromo, his most ambitious work, and the picture painted by Financial Times journalist Tom Burgis in The Looting Machine, a despairing, recent account of how corrupt local elites get into bed with anonymous multinationals and shadowy Chinese middlemen, the better to rape Africa. In Conrad’s Costaguana, hunger for the country’s silver deposits powers the narrative; today’s plunder is timber, diamonds, potash, coltan, and oil. As Poland’s most extraordinary export warned: “There is no peace and rest in the development of material interests. They have their law and their justice. But it is founded on expediency, and is inhuman.”