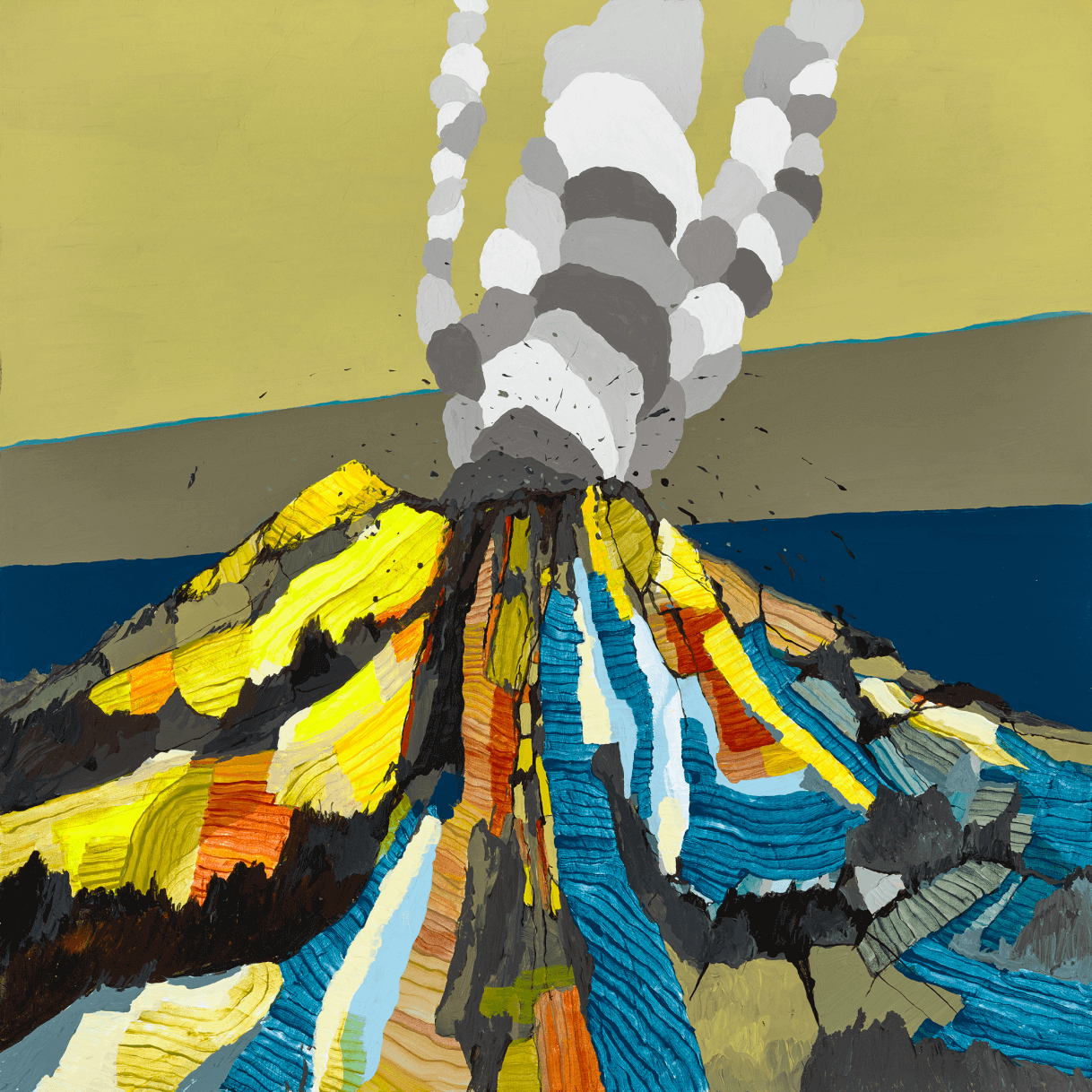

Ryan Molenkamp has lived in the Pacific Northwest his entire life and was just three years old when Mount St. Helens erupted in 1980. For the past four years, he has painted more than 106 works as a part of his “Fear of Volcanoes” series, which depicts various mountains—both real and imaginary—in states of turmoil or unrest. Here, he discusses the historical inspiration for the series, the real-life implications of active volcanoes, and why he doesn’t want to be known as the “volcano guy.”

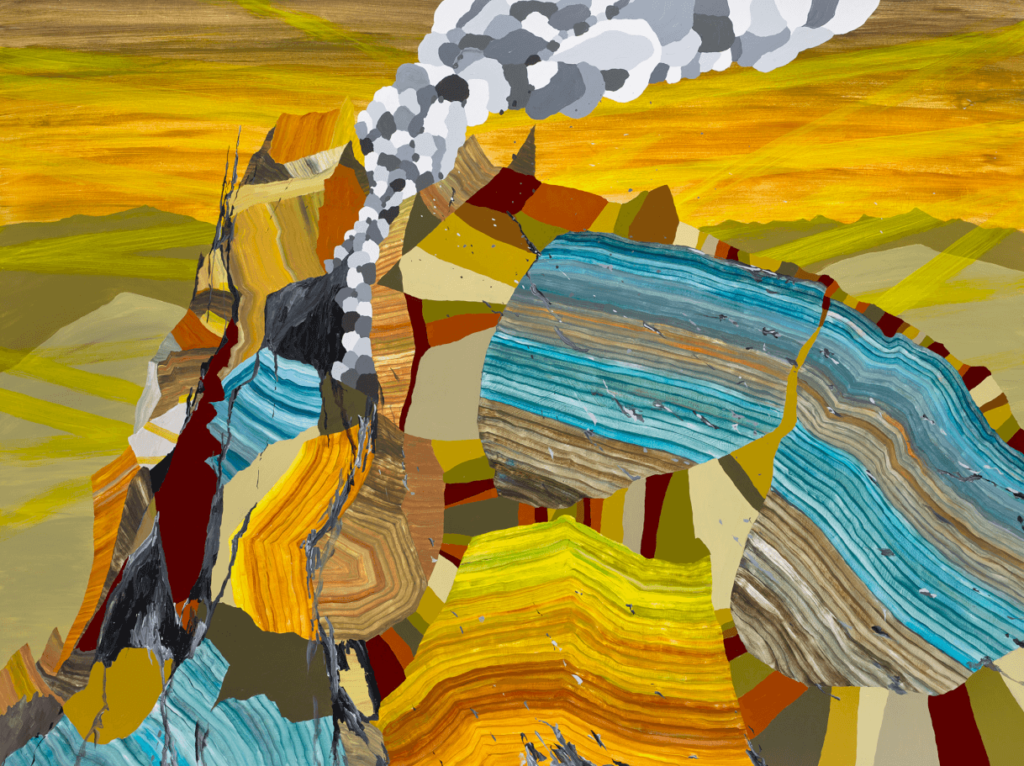

“I grew up mostly in Lake Stevens, Washington, which is at the foot of the Cascade Mountains. I also spent two years in Anchorage because my dad was in the salmon business, so he was working in Alaska throughout most of the year. And so that time definitely influenced my interest in the wilderness, in mountains, and in volcanoes—my work is informed by the landscape that I grew up in and inhabit now. I don’t remember the eruption of Mount St. Helens itself, but we traveled to the park shortly after that, when they opened up sections of it. I remember seeing the lines on the trees where the lahars had come through and finding big chunks of pumice on the ground. I had an interest in rocks and geology as a kid, so seeing that stuff stuck with me. The Everett Herald published a book that had photos of the eruption and the evacuation, showing the sheer scope of the damage—fallen trees everywhere—and I loved looking at a series of four photographs of the mountain erupting.

There have been quite a few paintings in my ‘Fear of Volcanoes’ series, but I still have new ideas that I want to explore within it. And there’s a danger—as there is with any art—of getting bored with it or boring your audience. But because there are so many possibilities for subject matter, I don’t know if I will ever get bored. It’s a two-edged sword to have a career defined by a specific style or a series of work: you don’t want to be known as the “volcano guy,” but at the same time, if people know you as the “volcano guy,” then at least they know of you. That’s useful in terms of having a successful art career, but it’s also the last thing you want to think about when you’re making work.

Real mountains inspire my paintings, but most of the time, I make a lot of changes to the imagery. I’ve never been interested in rendering an image exactly as it appears but exploring the things we do to the landscape—especially the way we interact with it, build upon it, and destroy it. In trying to control nature, we’re not going to leave much of a planet that’s livable for humans. We think we can control the earth, and then a volcano erupts—it’s just a reminder of the sheer destruction that nature is capable of, and how insignificant we humans really are to the planet.

Volcanoes do scare me, but I’m not waking up with nightmares of them or anything. I live right at the foot of these things, and they’re beautiful and dangerous. That’s very attractive, too—there’s a primal thing of nature and danger. But before Mount St. Helens erupted, there were periods of inactivity and relative calm, which is not unlike what’s happening with Mount Rainier right now. There are a lot of buildings along the rivers of Mount Rainier, and if that sucker goes, it’s going to be far more destructive than Mount St. Helens. These volcanoes also have the power to affect the entire planet, not just our local region—if they erupt, they could lower the temperature of the planet by several degrees and create a kind of nuclear winter effect. And let’s not even get started on the caldera of Yellowstone.”