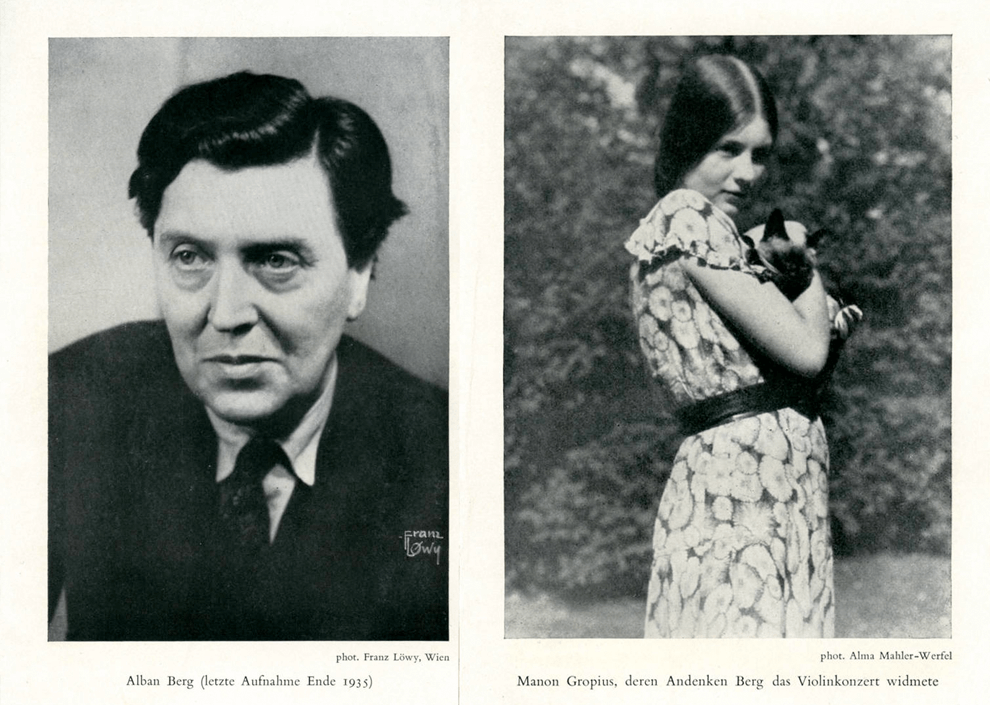

A few weeks ago, I saw the Canadian violinist James Ehnes perform Alban Berg’s Violin Concerto with the National Symphony Orchestra, under the direction of its music director, Gianandrea Noseda. It was an intensely moving, lyrical reading of a seminal 20th-century work—if ever one needed convincing that this 12-tone masterpiece is songful, tender, and achingly beautiful, this was the performance to attend. The concerto, Berg’s valedictory work, bears a famous dedication: “To the memory of an angel.” The celestial being in question was Manon Gropius, a girl of wide renown who had died from polio at the age of 18. Scholars now believe that the music also contains a hidden program—a tribute to Marie Scheuchl, a servant from Berg’s adolescence with whom he had an affair and an illegitimate child. A requiem, then, and a love letter too. What is less well known about the Berg Violin Concerto is the story of its premiere—one of the most tense and distressing, I’ll bet, in the history of music.

By the time Berg began writing his concerto in 1935, at the behest of the American violinist Louis Krasner, his health was in decline. Although he was hardly prolific and composed in a labored fashion, he worked feverishly on the piece that spring and summer, perhaps sensing that his time was short. He did so while ensconced at his country house, to the west of Klagenfurt, Austria, on the picturesque banks of the Wörthersee. When Manon died in late April, Berg decided to memorialize the girl who had enchanted the Viennese elite with her talent, beauty, and grace. The daughter of Alma Mahler (Gustav’s widow) and the architect Walter Gropius, Manon was, in her mother’s words, “a fairy-tale being; nobody could see her without loving her. She was the most beautiful human being in every sense. She combined all our good qualities. I have never known such a divine capacity for love, such creative power to express and to live it.” The writer Elias Canetti had a more objective perspective, yet he too was enraptured. In The Play of the Eyes, the final volume of his three-part autobiography, he described a “light-footed, brown-haired creature disguised as a young girl, untouched by the splendor into which she had been summoned, younger in her innocence than her probably sixteen years. She radiated timidity even more than beauty, an angelic gazelle, not from the ark but from heaven.”

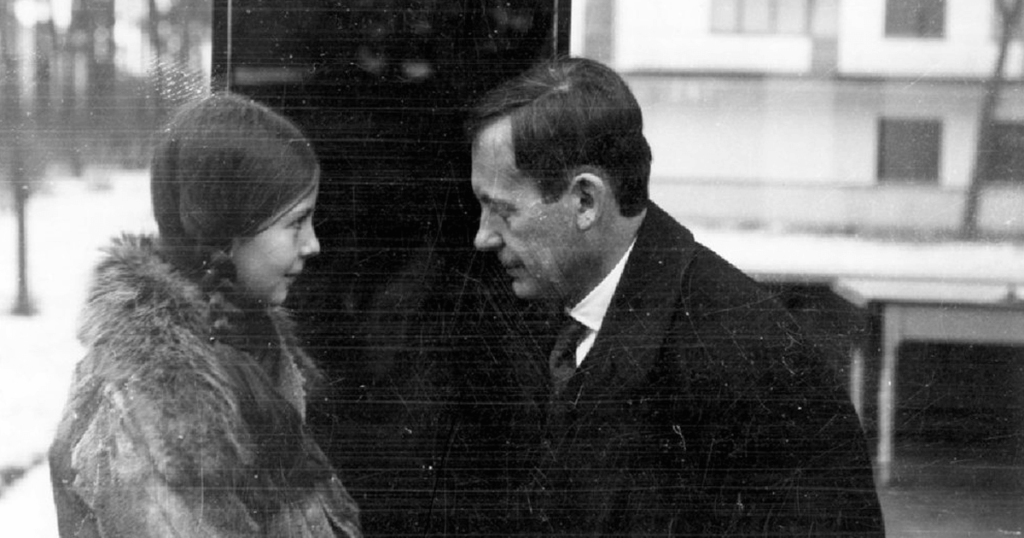

During an Easter trip to Venice in 1934, Manon contracted the polio that would paralyze her, confine her to a wheelchair, and lead to the failure of her organs. Her death was mourned by many (Canetti sketched a memorable description of the funerary procession from Vienna’s Heiligenstadt Church to the Grinzing cemetery), and especially by Berg and his wife, Helene, who thought of her as a daughter. The Bergs had no children of their own, and so it was Manon’s photograph that could be seen at Helene’s bedside.

The governing structural element of 12-tone music is the row—a sequence of the 12 notes of the chromatic scale from which all harmonic and melodic relationships are determined. For his concerto, Berg chose a row that allowed for both major and minor triads throughout the score. Thus does the music sound at once atonal and tonal, and the row made it possible for him to incorporate two tonal quotations into the work: a lilting, bucolic, Carinthian folk song as well as the Lutheran chorale “Es ist genug” from Bach’s cantata O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort (“I’m going to my heavenly home, / I’ll surely journey there in peace, / My great distress will stay below”). The concerto begins quietly, the rise and fall of the opening orchestral phrase echoed by eight notes on the solo violin—G-D-A-E E-A-D-G—played on the open strings, a sound that is utterly simple, utterly pure. From such simplicity, however, a work of incredible complexity and nuance evolves. The piece is by turns gracious and turbulent, tranquil and demonic, exuberant and solemn—a daunting challenge for both the soloist and the orchestra. Berg did not, however, live long enough to hear Krasner, or anyone else for that matter, perform it. While noting the score’s final details, the composer was stung by a wasp. A severe abscess resulted, and seven days after checking into a hospital, Berg was dead from blood poisoning. His great violin concerto, then, turned out to be a requiem for two.

Other than Helene Berg, perhaps nobody took the composer’s death harder than his close friend Anton Webern, who sank into a profound spell of depression. He and Berg had studied together with Arnold Schoenberg, the three of them subsequently becoming the leading lights of the Second Viennese School, fighting against merciless critics and an often-hostile public, yet convinced that their musical language was the true way forward. In January 1936, Webern wrote to Schoenberg: “There goes one of us (who were only a mere three), and now we two must bear this isolation alone.” Too heartbroken to attend Berg’s funeral, Webern knew that the Violin Concerto had to be performed as soon as possible. As president of the Viennese chapter of the International Society for Contemporary Music, he journeyed to Barcelona, determined to get the concerto scheduled at the society’s annual festival, to be held that spring in the Catalonian capital. He succeeded. Louis Krasner was engaged as soloist. Webern would conduct.

As he spent more and more time with the score, however, Webern’s depression worsened, the responsibility of introducing the work to the world weighing increasingly upon him. By the time he and Krasner journeyed to Barcelona together, in April 1936, he was very much regretting his decision. Sure enough, the rehearsals were a fiasco. The musicians of the orchestra had trouble coping with their complex parts—and with Webern’s perfectionist tendencies—and furthermore, could make little sense of the conductor’s heavily accented Viennese German. Webern sensed disaster and grew more paranoid with each passing minute. Finally, he suffered a breakdown. He declared that the performance simply could not take place. He seized the conductor’s score (the only copy), fled to his hotel room, and locked himself inside.

Only when Helene Berg intervened—upon gaining access to Webern’s room, she knelt down before him in tears, pleading with him to relinquish the score—did he relent. Webern returned to Austria mortified and embarrassed, forcing the conductor Hermann Scherchen to step in. He pulled an all-nighter with Krasner and conducted the concerto’s premiere after just one rehearsal.

Krasner would later blame Webern’s poor conducting abilities for the debacle. Yet Webern’s podium technique was well noted; he had led many distinguished ensembles in both traditional and contemporary repertoire. Indeed, Berg considered Webern to be the finest conductor since the death of Mahler. Krasner’s irritation may have had another source, stemming from their journey to Barcelona. In those days, the most sensible route to Spain would have bypassed Nazi Germany entirely, cutting through Switzerland and France instead. Webern, however, in the full bloom of his naïveté, insisted that no harm could possibly come to the Jewish Krasner if the two of them journeyed by train through Germany. No matter that the Nazis had branded Webern a “degenerate” and banned his music, or that his dearest friend, Schoenberg, had already escaped to California. Krasner was incredulous but went along, and in the end, nothing happened. Still, the grave and harrowing risk they took may have turned him, understandably, against Webern.

Nevertheless, two weeks after Barcelona, they collaborated on the Berg Violin Concerto in England, with Webern leading the BBC Symphony Orchestra (an ensemble he knew well). To say that the performance was successful is something of an understatement. For me, there is no finer account of the concerto than this—the only example of Webern’s conducting on record—serene and majestic, tormented and pure, an interpretation as authentic as can be, given how intimately the soloist, and especially the conductor, knew the composer and his idiom. The affair in Catalonia may have been Webern’s lowest point, but the concert in England soon thereafter was one of the glorious triumphs of his life.

Listen to Louis Krasner play the Berg Violin Concerto, with Anton Webern leading the BBC Symphony, from this live concert held on May 1, 1936: