A professor of painting and drawing at the University of Washington, Philip Govedare has been painting landscapes for the entirety of his career, and his work has been exhibited across the country. Here, he discusses why his depictions of the environment aren’t site-specific and how he navigates the difficulties of portraying the contemporary landscape in the midst of climate change.

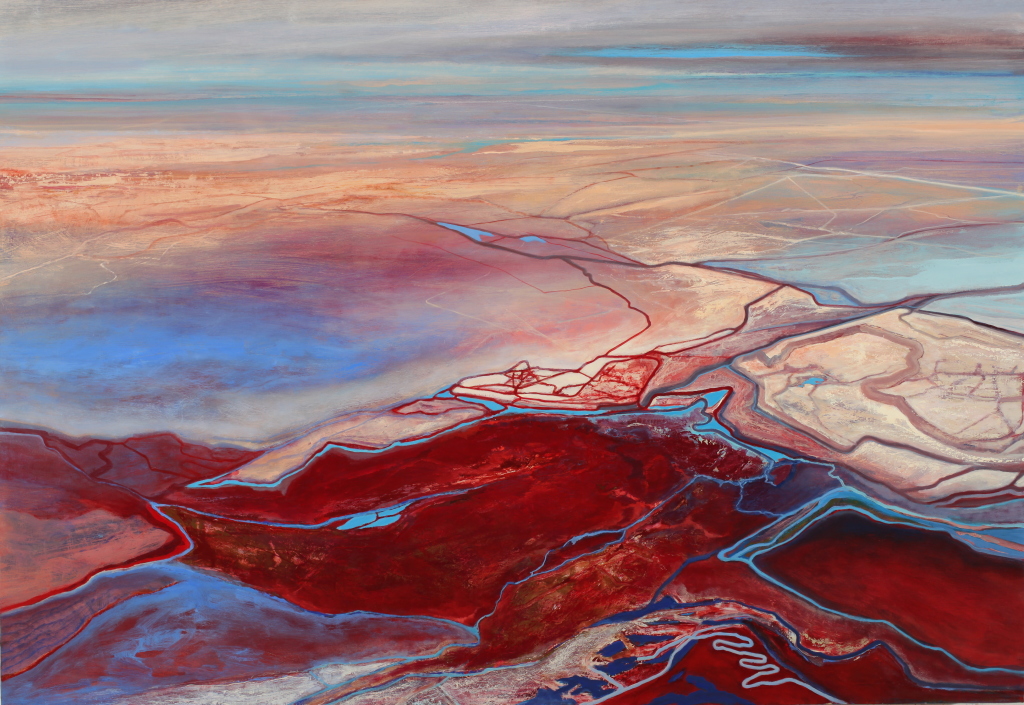

“Growing up in a small town in eastern Oregon, my relationship to nature has always been important. That may be why I chose landscape as my subject for painting. The experiences you have growing up are formative to your sensibilities and how you see the world. My paintings are informed by observation and the experience of being in a particular place. But they’re really the intersection of imagination and a feeling—they’re not referential to any specific site in the real world. I don’t use photography, except as a means to remember something that interests me. I like being in the landscape, and I do drawings onsite to remember things I have seen. I’ve worked a bit in southern Utah, and that sense of vastness and monumentality has inspired me. But the big paintings are done in the studio through an exhaustive process, arriving at a place that comes mostly from my imagination, but which is informed by the experiences of being in the landscape. I work with color and atmosphere to arrive at a quality of light, and then I start imposing certain structures that I’ve seen. These allude to geological formations or rivers, but also the imprint of development, like roads and structures that are human-made.

I’m very much aware of how we’ve changed the biosphere of the planet since the Industrial Revolution. As a species, we have become a geophysical force and changed the course of evolution for life on earth. So that is something that is a backdrop for how I see landscape. The kinds of changes that are taking place are visible, in terms of development, but also there are changes that are partially visible or invisible because of pollution, changes to the conditions of the atmosphere and climate change. And that’s one of the challenges of painting: How do you represent a contemporary landscape and pose these questions about our relationship to nature without being overbearing? The landscape seen from a great distance is vast and evokes the eternal. It can be unsettling and humbling. And while my work may allude to the more troubling aspect of human development and the environment, I would ultimately like my paintings to inspire awe, wonder, and elicit questions about our place in the world.”