The Letters of Sylvia Plath, Volume 2: 1956–1963, edited by Peter K. Steinberg and Karen V. Kukil; Harper, 1,088 pp., $45

The story of Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes began as a kind of fairy tale, or—to be more contemporary—a True Romance. When we last encountered the lovers, at the end of the massive first volume of Plath’s letters, they were addressing each other in passionate prose: Sylvia was Ted’s “kish and puss and ponk”; he was her own “Teddy-ponk.” Volume two begins with the same romantic enthusiasm, as Sylvia tells American friends about her secret Bloomsday marriage to a “roaring hulking Yorkshireman,” “exactly the sort of person I’ve always needed [a] strong brute with dark hair, in great unwieldy amounts, & green-blue-brown eyes [who] sings ballads, knows all Shakespeare by heart” and is not only her erotic ideal but her literary and spiritual soulmate.

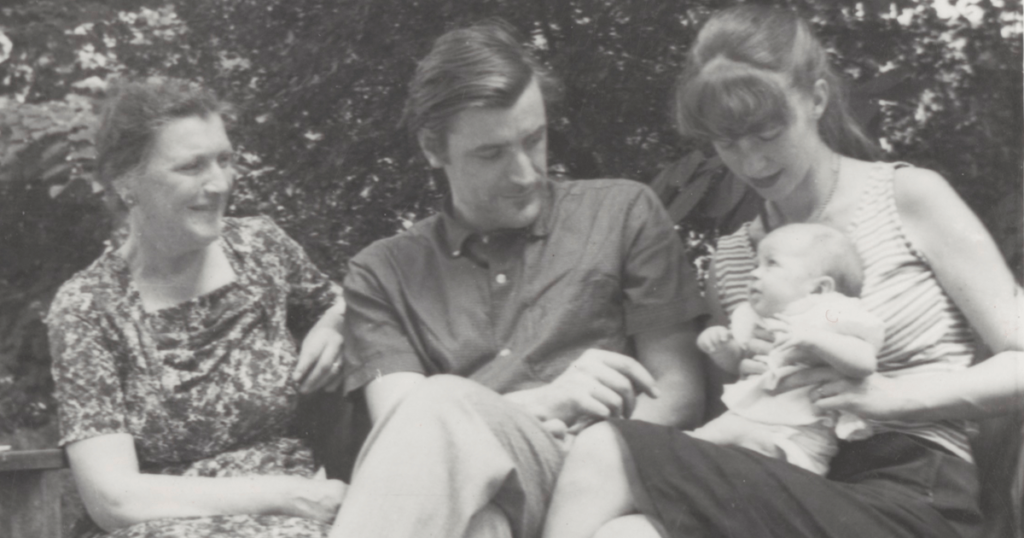

Too good to be true? It might seem so, but the portrait of a marriage that Plath limns throughout most of these pages is ecstatic. In the first five years of their communal life, the preternaturally gifted pair virtually conquer the literary world. Ted publishes two books of poems, captivates BBC audiences, wins prize after prize. Sylvia publishes a first book of poems, writes and sells a novel, and regularly appears in The New Yorker, Poetry, The Atlantic Monthly, all while vigilantly housekeeping, inventively cooking, beekeeping, and home-birthing and nursing two babies. Together the two teach undergraduates (at Smith and the University of Massachusetts Amherst), travel the States, reside at Yaddo, spruce up a shabby London flat, vacation in France, then finally move to Devon, where they take on the painstaking task of renovating Court Green, an 11th-century farmhouse with a thatched roof and a view of “a wall of old corpses,” a yew tree, and an impassioned elm. At the center of all this activity, a dream invitation that would transport any aspiring young poet to literary heaven: dinner at the home of T. S. Eliot and his wife, Valerie, along with another couple, Stephen Spender and his wife, Natasha. Plath’s description of the scene was glowing: she had “[f]loated in to dinner and “sat between Eliot & Spender, rapturously,” she told her mother. And this was the sort of thing that kept on happening while the couple, who then seemed touched by magic, was still living in London.

Court Green, in North Tawton, Devon, was another matter. The house was huge and hard to furnish, and its gardens had been taken over by stinging nettles. Plath was pregnant with her second child, Nicholas, but at first she found the “utter peace” quite “heavenly.” At last the two poets had studies of their own, their daughter, Frieda, had a playroom, and there would be ample space for the many children Plath said the two of them wanted.

Within a few months of Nicholas’s birth, the charm of extra space disintegrated rapidly, as did the peace Plath had initially felt. Though there were wonderful moments—for instance, when the garden bloomed with astonishing masses of daffodils, about which both poets wrote—the loneliness and rigor of country life, together with the sheer arduousness of caring for two little children while keeping house in an old manor without central heating and a modern kitchen, exhausted the pair. “We can hardly see each other over the mountains of diapers and demands of babies,” she told her mother.

The story of what happened next is perhaps too well known to recount, and it emerges only fitfully from the letters. How Assia and David Wevill, to whom the couple had sublet their London apartment, came for a weekend, with the glamorous Assia having already confided to a colleague that she planned to “seduce Ted.” How Ted fell for Assia right away. How Sylvia, with what her husband called her “death-ray quality,” intuited that something was wrong. How Ted sent Assia a love note. How Assia responded affirmatively with a symbolic blade of grass in an envelope. How the lovers met and steamily copulated in various hotel rooms. How Assia called Ted, speaking in a pseudo-masculine voice, and Sylvia, picking up the phone before he could get to it, tore the black machine out of the wall “by its root.” How her mother, Aurelia, came for a visit and saw so much marital discord that Sylvia was horrified and humiliated. How Sylvia forced Ted out but sought for his return. How Frieda said, “Where is daddy?”

The frantic letters toward the end of this volume tell the dire tale of the separation—Plath’s dreary, even scary autumnal months alone in the big old house with two young children and, sometimes, no nanny; her vexed trip with Ted to Ireland, where he abandoned her after four days to sneak off to Spain with Assia; her hopeful but ultimately horrific move to Yeats’s former house in London; her ambivalence about her future. Most revealing are the desperate missives written to her American psychiatrist, Ruth Barnhouse Beuscher, powerful new contributions to our understanding of Plath’s emotional state throughout her life but especially in this period.

As Frieda Hughes, the lone survivor of the Hughes-Plath-Wevill melodrama, notes in a moving forward to the book, these letters function as “snapshots” of a marriage that crashed during “what would be an unsustainable idyll” in pastoral Devon. Now, as the pastoral devolved into the purgatorial, Plath gasped out painful assertions to her distant reader. Ted had never wanted children, and in particular disliked Nicholas: “He has never touched him since he was born, says he is ugly and a usurper.” Earlier, back in London, she had had a miscarriage a few days after “Ted beat me up physically” because she had angrily torn some of his papers in half. Ted “has never paid a bill” and has no idea of the family’s finances. Worse still, she confesses, are her fears that she will turn into a replica of her mother, who suffered in her marriage and was widowed early. Plath wrote to Beuscher, even “while she [Aurelia Plath] was here she began it: ‘Now you see how it is, why I never married again, self-sacrifice is the thing for your two little darlings etc. etc.’ till it made me puke.” But then, again, the poet’s thoughts obsessively return to Ted and his “girl”: “I am just dying. I could stand tarts. She is so beautiful, and I feel so haggish & my hair a mess & my nose huge & my brain brainwashed & God knows how I shall keep together.” Yet “I still love Ted, the old Ted, with everything in me & the knowledge that I am ugly and hateful to him now kills me.”

A month later, on the verge of moving to London and no doubt revitalized by the stunning advent of her great Ariel poems, she confides to Beuscher that she is on the upswing. Ted “was furious I didn’t commit suicide, he said he was sure I would!” she writes in a passage whose irony is too poignant to bear, but “I see … that domesticity was a fake cloak for me” and now “I like being alone … being my own boss. … I am so happy, everything intrigues me, I have become a verb, instead of an adjective. It is as if this divorce were the key to free all my repressed energy.”

Alas, the energy dissipated under the strain of the move to London, the infamous “snow-blitz” that hit the city in the winter of 1963, and the bouts of flu that felled Plath along with her two children. By February 4, 1963, when she wrote her last letter to Beuscher—the final letter in the volume—she knew what was happening to her: “the return of my madness, my paralysis, my fear & vision of the worst.” Her loyal London doctor struggled to get her a hospital bed but couldn’t find one in time. Her cry across the Atlantic told a ghastly truth: “I am suddenly in agony, desperate, thinking Yes, let him take over the house, the children, let me just die & be done with it [though] Now the babies are crying, I must take them out to tea.”

A week later, of course, she was to “die & be done with it.” This last letter suggests that her suicide was not—as some biographers have thought—a call for help but a deliberate act of self-destruction. She had fought the impulse to die, but now she wanted everything to be over; she was no longer “a verb.” Writes Frieda Hughes, in a sentence that offers a fitting epitaph to a marriage of heaven and hell, “the spark of my parents’ first meeting ignited a fire, which then burned so brightly in the microcosmic universe they constructed for themselves that they ran out of oxygen.” At least, Sylvia Plath ran out of oxygen, as she turned on the gas and entered the world of “Dachau, Auschwitz, Belsen,” which she had described so sardonically in her poem “Daddy.”