No Harmony in the Heartland

Two small towns in northeast Iowa are caught up in the national struggle over immigration

In the summer of 1893, the Czech composer Antonín Dvořák took his wife and six children to the frontier town of Spillville, Iowa, for a three-month stay. This was not a random choice. Having arrived in America the year before, Dvořák had been living near Gramercy Park in New York City and working as the director of the National Conservatory of Music of America. Though he had managed to compose his Symphony No. 9, From the New World—a grand triumph at its New York Philharmonic premiere and to this day his most popular work—the babble and chaos of the city grated on his nerves.

The composer’s secretary, Josef Kovařik, who had accompanied him to America, offered a suggestion: Why not take a vacation in Spillville, a prairie town populated almost exclusively by immigrant Czechs? This was where Kovařik’s father lived and worked as a schoolmaster. It was an idyllic place where Dvořák could speak Bohemian on the dirt streets, drink pilsner, play the card game darda with his countrymen, perhaps find some further inspiration for his music.

Upon his arrival there, Dvořák did all of that and more. He took early-morning walks along the Turkey River and found a stump of a white oak on which to sit and listen to songbirds. He played the organ in the loft of St. Wenceslaus Catholic Church during morning Mass and strolled the brick sidewalks in the evening under kerosene lamps. People in town began to call him “the master.” He would later describe the summer as among the happiest of his life.

He wrote in a letter home: “These people—all the poorest of the poor—came about forty years ago, mostly from the neighborhood of Pisek, Tabor, and Budejovice. And after great hardships and struggle, they are very well off here. I like to hear stories about the harshness of the early winters and the building of the railroad.” The residents of nearby frontier towns expressed a grudging admiration for the industriousness of the Bohemians in Spillville but also frowned on their drinking, their ineptitude with English, their Catholicism, and their clannishness. In larger cities such as Chicago, the Czechs picked up an unflattering nickname: bohunks, or hunkies, the likely antecedent of the slur honky.

This past Independence Day weekend, 125 years after that Dvořák summer, I went to Spillville, to a city park not far from the white oak stump upon which the composer had sat. The town has a population of approximately 350—almost exactly what it was in 1893—some of whom are the great-great-grandchildren of those who heard Dvořák play the organ at St. Wenceslaus. Most still have Czech names. Their neighbors no longer consider them suspicious. On the day of my visit, hundreds of people from the region had descended upon the town, spreading blankets on the grassy part of a baseball field, eating ice cream, and watching their children chase each other around the evening shadows, while waiting for the start of what I’d heard was the best fireworks show in northeast Iowa.

It had been an uneasy year in this part of the state, especially when it came to the subject of immigration. After President Trump instituted a policy to separate young children from their asylum-seeking parents at the U.S.-Mexico border, some in Iowa worried that—after a long period of easing tensions—federal agents were going to once again raid meat-processing plants that employed foreign laborers. Anxiety over immigration was also threatening to spill into the upcoming congressional election between the incumbent Rod Blum, a 63-year-old Republican millionaire with roots in the Tea Party, and Abby Finkenauer, the 29-year-old daughter of a union pipefitter and welder and a rising star in the Democratic party.

I drank a beer with Randy Ferrie, a 59-year-old supervisor for a company that makes horse trailers in the nearby town of Cresco, and asked him about the election. He told me he didn’t like the new closed-door attitude of the United States.

“It wasn’t like this when I was younger,” he told me. “A lot of people in this country are indeed very generous, but to be honest, we’ve gotten selfish and stuck up. Now it’s about, ‘If new people coming here doesn’t benefit me, why would I want to help?’ The American Dream is eroding, and it is scary.”

Ferrie said that although business was good, he was having a hard time finding qualified laborers. The answer, he said, was simply to make coming here easier. “If we want to have business or manufacturing, then we need to have bodies.”

The fireworks began, and we paused to watch the red, green, and purple flashes exploding in the summer sky, reflecting off hundreds of upturned faces. A recorded medley of Van Halen, Lee Greenwood, and a Kate Smith imitator singing “God Bless America” boomed from a set of outdoor speakers while the fireworks fizzed off from three battle stations on the lip of a nearby sewer lagoon. A lightbulb display flashed military iconography: a jet, some tanks, clustered soldiers lifting a flag Iwo Jima–style. And the inevitable finale of a multicolored cannonade, which left the air fragrant with sulfur.

Most people folded their blankets, trashed their ice cream wrappers, and joined the scrum of cars inching for the exit at Highway 325, but about three dozen hardcores stayed to drink more beer inside the Inwood Ballroom, a wood-framed dance hall built in the early 1920s that has been expanded and lovingly restored over the years. Bobby Goldsboro and Louis Armstrong, Glenn Miller and Lawrence Welk all played here on their tours through corn country. Tonight’s act was a band called Yukon, featuring the mayor of Spillville, Mike Klimesh, on lead guitar. He wore his blond hair in a large swoop on top with buzzcut sides and a red plaid button-down over a T-shirt with the legend “I’m a Badass.”

Klimesh is a direct descendant of one of the six Czech families that founded Spillville in the 19th century, and he has a pragmatic view of his mayoral post, which he has held for nearly two decades. “I’m like a plumber,” he told me. “When they flush the toilet, they want to know the shit stays gone.”

Like many who live here, he’s a lifelong Republican. The rural precinct in which Spillville is located came out heavily for Donald Trump in 2016, by a 30-point margin over Hillary Clinton. “They weren’t Trump supporters so much as Republican presidential candidate supporters,” Klimesh explained. “Their tolerance is based on neighborliness. I can be conservative about my guns and the government sticking its nose where it doesn’t belong. But I’m not paranoid about immigrants.”

As the mayor’s band launched into a cover of “Copperhead Road,” I stood next to a farmer with a baseball cap and a Czech last name. He swayed gently back and forth and told me he would vote for the incumbent president even though the recently announced tariffs on soybeans would cost him thousands of dollars.

“It’s going to hurt, but we have to get through it,” he said. “We have to shake things up. We have to make things right again.”

The state that novelist and short-story writer T. C. Boyle once called “the Mesopotamia of the Midwest, the glorious, farinaceous, black-loamed hogbutt of the nation,” is often held up as a bellwether for the collective American mood, and this has a lot to do with Iowa’s outsize role in electing presidents.

Its quadrennial January caucus—conceived in the early 1970s as a way to strip nominating power from party elites—takes place not in the solitude of the voting booth but inside school gymnasiums, living rooms, church basements, anywhere that neighbors can gather, politely talk among themselves, and cast their votes to steer our national destiny in ways that resemble a lithograph of old-style, face-to-face democracy.

Politicians are expected to court favor in the same ponderous way: by buttonholing those of voting age at county fairs or on the street, and eating enough dinners in the reserved back room of the local Golden Corral to double their diastolic blood pressure. As an old local joke goes, a farmer is asked if he’s going to vote for a particular famous presidential candidate. “Don’t know,” he answers. “I haven’t met him yet.”

Wikimedia Commons

The U.S. representative of the district that includes Spillville, Rod Blum, supported Trump’s ban on travel to the United States by residents of seven predominantly Muslim countries. He told me in an emailed statement that although he wants to improve the visa program for farmworkers, “the massive influx in illegal immigration is driving down wages and making jobs less lucrative for those here legally. This must end.”

Finkenauer, his opponent, broke out of a crowded Democratic pack in part with a campaign video in which she held up her father’s welding sweatshirt, covered in burn marks. “I’m running for Congress so families like mine have a champion in D.C.,” she said. But immigration didn’t figure heavily into her message. No statement about her position appeared on her website until deep into the summer, and even then, it largely rested on platitudes.

I went to hear her speak at the opening of a Democratic Party office in the city of Decorah, and the crowd was so big that the event was moved to a larger space next door. After the customary thank yous and warm-up speeches from local office seekers, Finkenauer got up and spoke in the flat-vowel accent particular to the Upper Midwest.

“This does the heart good to see this,” she said. “Folks in Iowa care about others. That’s who we are. We are not a country or a state that grows out of fear and division. We grow out of hope. That’s what’s on the line—hope. The future of our state is on the line here.”

It wasn’t a bad five-minute stump speech, though it was devoid of specifics. I edged out to the sidewalk in hopes of asking her a question on immigration. Several emails to her campaign had previously gone unanswered. When I had visited her Dubuque office, her staff promised me callbacks that I never received.

I introduced myself, and she smiled, but when I mentioned the word “immigration” in connection with the race, an unhappy look crossed her face. “We need commonsense immigration reform that treats everyone fairly,” she muttered, barely above a speaking voice, and moved away quickly down the sidewalk, as if embarrassed.

Her campaign also went mum about a notorious incident on the western side of the district—the arrest of a migrant from Mexico in connection with the murder of 20-year-old college student Mollie Tibbetts. National conservative media jumped all over the story as supposed evidence of an immigrant crime spree. Blum used the incident to rail against “sanctuary cities.” Finkenauer offered prayers to the Tibbetts family over Twitter and said little else.

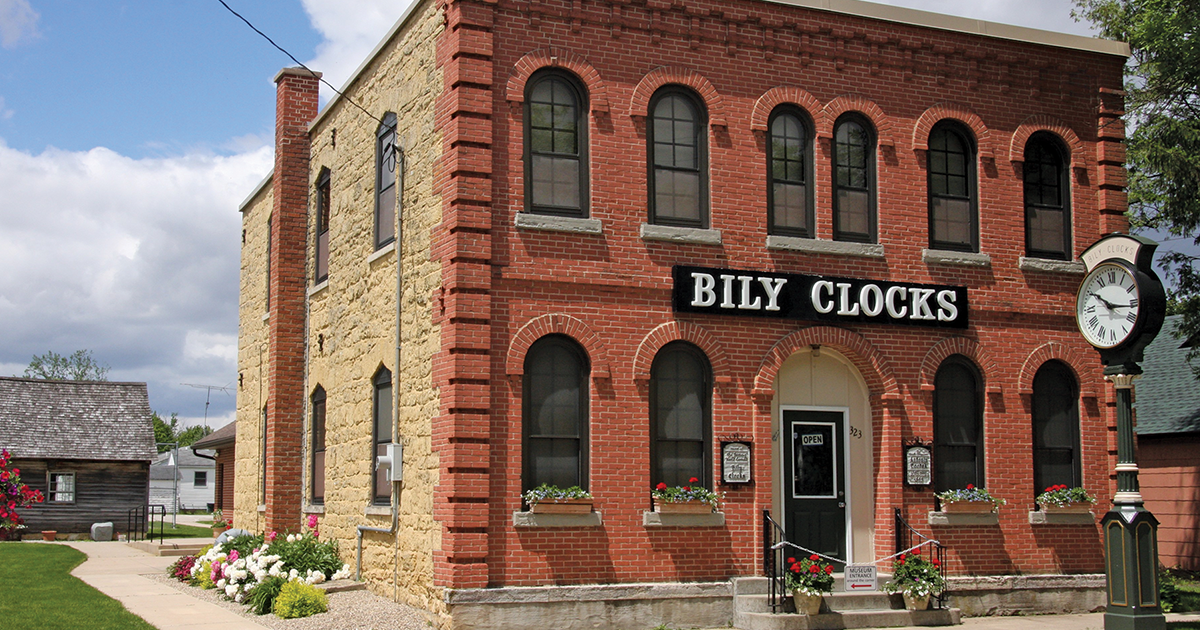

The house where Antonín Dvořák lived, as it is today; while there, the composer completed his String Quartet, op. 96, commonly known as the American. (Courtesy of the Bily Clocks Museum)

A longtime observer of the Iowa political scene, who could not speak on the record because of his job, told me that the sine qua non of state politics is the quality of neighborliness. Does a politician seem likely to help a stranger out of a jam? To listen to country music and drink a Budweiser with you? To solve a problem in a practical way while looking you in the eye? The last Democrat to have held this seat, Bruce Braley, lost his race for the U.S. Senate in 2014 at least in part because of a public mistake he made when a neighbor’s chickens had strayed onto his vacation property. He threatened legal action—a brazen violation of rural protocol.

Being neighborly, however, can get complicated when the neighbors happen to be new immigrants. Iowa’s conflicted legacy on immigration can be traced back to 1975, when the state’s Republican governor, Robert Ray, bucked elements of his party to accept more than 1,000 refugees from Southeast Asia. In recent years, in addition to immigrants from Mexico and other parts of Latin America, small clusters of Bosnians, Liberians, and Congolese have arrived.

“We’re very cautious about it,” the political observer told me. “It’s the toughest issue anyone faces. The polling numbers are not good. Immigrants save Main Streets, they save these little towns, but there’s so much frenzy around the issue.”

“I was raised in an atmosphere of struggle and endeavor,” Dvořák liked to tell his music students. He was the son of a butcher, and it was expected of him that he would go into his father’s trade. But he was spared the life of the block and the cleaver when his aptitude for music persuaded his father to allow him to pursue it as a career. He learned the violin, then later the piano and the organ, which he played during church services as a teenager, while living with his uncle in the Bohemian town of Zlonice. His rise to international prominence as a composer was gradual, though by the time he arrived in America, he was an eminent figure, admired for his symphonies, concertos, and chamber music. No matter how welcome it must have been, leaving New York for the vast expanses of northeast Iowa must have caused something of a shock.

“It is very strange,” Dvořák wrote to a friend back in Bohemia, describing the open spaces that he found at once intoxicating and alienating. “Few people and a great deal of empty space. A farmer’s nearest neighbor is often four miles off. Especially in the prairies (I call them the Sahara), there are only endless acres of field and meadow and that is all. You are glad to see in the woods and meadows the huge herds of cattle which, summer and winter, are out to pasture in the broad fields. And so it is very ‘wild’ here and sometimes very sad—sad to despair. But habit is everything.”

Spillville is on the edge of the physically lovely Driftless Area, which was spared the flattening impact of the glaciers during the last ice age and is thus characterized by dramatic hills and ridges that can remind the viewer of Provence. Vistas extend across 20 miles of small groves, hayfields, tidy farmhouses, and lonely silos. Corn is the big crop here, almost all of it meant for livestock feed, and it is planted in robotically precise configurations by mechanized planters guided by GPS technology.

Open space between two towns in the Driftless is dominated by an unbroken tableau of broad corn leaves waving in the breeze, but every now and then, a traveler passes a hog barn with big exhaust vents. Somebody has to feed the hogs, change the heat setting, shovel the manure, and move the hogs to processing, and this is the source of a good percentage of Iowa’s subterranean workforce that few want to talk about. The laborers live discreetly, often in basic housing on the farm itself. According to a recent study by three Iowa State University economists, American pig farmers spent more than $837 million on temporary labor in 2012, paying out increasing sums of money for low-status jobs that few Americans will do.

The more visible concentration of immigrants is in the slaughtering facilities of major meatpackers. About 20 miles down the road from Spillville is the larger town of Postville, which has a sign on the edge of U.S. Highway 18 proclaiming it to be the “Hometown to the World.” Not long after that, you pass the reason why: a processing plant called Agri Star Meat and Poultry.

In many ways, Postville is arranged—literally and economically—like a perfect company town in which every dollar flows from the factory gates. Such towns are often brutal, but they have a rawness and honesty about them that the immigrants of Dvořák’s time would have recognized instantly. Loyalty equals survival: loyalty to the bonds of work, company, family, and ethnicity. In this sense, Postville has changed very little, even as its racial demographics have shifted, something its neighbors regard with a mild sense of alarm. Where else in the midwestern Corn Belt will you find, on an ordinary downtown street, African men wearing flowing Islamic robes, black-suited Orthodox Jews with curly peyos, and a Mexican evangelist preaching the risen Christ through a loudspeaker?

The transformation of Postville into an immigrant-heavy Iowa town began in the 1980s with a hunch by a Brooklyn butcher named Aaron Rubashkin, who specialized in custom kosher meat for the borough’s growing population of ultra-Orthodox and Hasidic Jews. But transporting cattle to New York for slaughter under rabbinical supervision was expensive. Could industrial livestock slaughter—a specialty of the Midwest since the days of the 19th-century Chicago feedlots—be married to a regimen of rabbinical oversight? And could a new market be developed among younger Jews who wanted to broaden their religious life by way of the kitchen table? Rubashkin wanted to find out.

According to Stephen G. Bloom in his book Postville: A Clash of Cultures in Heartland America, Rubashkin bought Postville’s old HyGrade plant, renamed it Agriprocessors, and persuaded a staff of rabbis to move out to rural Iowa to certify that steers and chickens were killed according to kashrut standards, then developed methods for vacuum sealing and shrink-wrapping that kept the meat fresh for weeks. His business sense proved correct: sales were immediately strong, and annual revenues eventually reached $250 million. But Rubashkin and his son Sholom also developed a reputation in Iowa as bad neighbors who stiffed creditors on their bills, dumped effluent in streams, harassed union organizers, and started arguments among rabbis over what some considered sloppy and unnecessarily cruel practices on the kill floor.

The end of their reign came on May 12, 2008, when U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents raided the plant and arrested 389 people for various immigration-related offenses. Buses took the arrestees to the city of Waterloo, where, inside an improvised federal “courtroom” located in a cattle fairgrounds hall, most were sentenced to five months in prison and later deported. Sholom Rubashkin denied knowledge of the illegal workers, but he was eventually charged with 67 violations of child-labor law. He was found not guilty but received a 27-year federal sentence for financial crimes (President Trump would commute his sentence in 2017). Postville lost a quarter of its population practically overnight, and Agriprocessors went bankrupt within six months.

Pledging to operate a more ethical business, a new set of Jewish owners bought the plant in 2009, renamed it Agri Star Meat & Poultry, repainted the water tower, spent $7.5 million to renovate the decaying plant, and brought in a crew of legalized Somalian refugees who had been living in Minnesota and Wisconsin. Guatemalans and Mexicans also started to come back, and today, the factory is once again paying an average of $9 per hour to approximately 350 workers who kill, disembowel, and partition livestock.

On a bright morning in July, I met Nathan Thompson, a young employee of the Northeast Iowa Resource Conservation and Development office, who took me on a walk around Postville I will never forget.

He first pointed to an old two-story, red-brick hall next to his office. “That’s the Turner Hall,” he said. “There were lots of these in German-American communities all over the Midwest. They were like a gymnasium, an opera hall, and a social service agency all in one. Kind of like a YMCA. The German roots of this place go pretty deep: the Mass at the Lutheran church was said in German up until the 1950s.”

We then crossed Lawler Street and went into a combined restaurant-carnaceria named El Pariente, run by a man in his 50s named Ricardo Garcia. By any measure, he is an American success story. Born in Aguascalientes, Mexico, he crossed the border and took a job in a slaughterhouse in Glendale, Arizona—work he didn’t enjoy. But he was known as a charismatic man with functioning English, Hebrew, and Chinese who could round up a lot of employees on short notice. One day he got a call from the owners of Agriprocessors, who offered him a job as a supervisor on the condition that he bring dozens of Mexican and Central American laborers with him.

Spillville’s school (left) and St. Wenceslaus Catholic Church (right), as shown in a 19th-century photograph. The town’s population is still 350. (Everett Collection)

“I told them that I’d need them to guarantee there would be places for these guys to live,” Garcia said, “some cash deposits on housing, and a little food money before they got their first paychecks. Otherwise, don’t waste your time dealing with me.” The owners came through, and they had their workers within six weeks. The new arrivals soon bore the telltale signs of work in an abattoir: bent fingers, scars on their lower arms.

“I don’t really like being here,” Garcia told me. “But I love the business opportunities.” Too many people in town do drugs, he said, and many of the white residents give subtle and overt snubs to the Latinos. “When I was younger, I fought all the time. Ruined a lot of relationships. Now I just let it go in one ear and out the other. It will one day be a good town. We’re not there yet.”

Thompson and I then went around the corner and found a group of black men in long robes and short rounded caps called taqiyah, sitting in plastic chairs and gossiping in Somali. In a different time in Iowa, in Dvořák’s time, they might have been old German farmers in overalls, cracking jokes and complaining about the weather. Thompson pushed the door into what is now called the Juba Grocery & Halal Market and introduced me to Ibrahim Sharif, a slender man wearing a purple button-down shirt and business slacks. Originally from Somalia, he worked at Agri Star for five years but has since gone into business as a seller of basic household goods and the occasional delicacy of camel meat. He tells me he closes the store three times a day for Muslim prayers. His competitor in North African goods across the street shares a wall with a synagogue, the Congregation Degel Machane Yehuda Stretin, which itself stands near the Iglesia Apostolica de Cristo and a nameless storefront mosque with sheets taped up in the windows.

A few doors down from the Juba grocery is the simply and elegantly named Kosher Market. Racks of tinned borscht, crackers, candy, and other goods with Hebrew labeling stand in front of glass-doored coolers containing beef products bearing the labels Aaron’s Best and Shor Habor—the big national brands used by Agri Star, which is just down the street.

I talked with Yaakov Yitzak, a native of Israel with roots in Argentina, who wears a baseball cap emblazoned with the Brazilian flag. “Around the world, there are problems between Muslims and Jews, for sure,” he said over the counter. “But when somebody is right in front of you, they are your friend. We didn’t create the world, we only live in it, and we have to accept it.”

He was articulating the basic rule of Postville, Iowa, which functions in the classic state of cultural détente known to multiethnic cities such as Beirut, Montreal, Dubai, and Hong Kong, all founded on keeping the peace among different races and religions in the name of a liberal capitalism that accepts anybody willing to work.

Back in Spillville, at the Farr Side bar, a farmer named Jerry, on his third Calvert whiskey sour of the night, held forth on the peril facing the country. “What good do these immigrants do us?” he said to a small crowd gathered near his stool. “All they want is to take our welfare and send it back to their home country to make bombs.”

Sitting next to him was Lisa Costello, a dental assistant who, like the farmer, voted for Trump. She has gotten to know several Mexican migrants and their children through her practice, and she offered some mild pushback. “They are hard workers, Jerry. They are here to make the most for their families. But I agree with you that this has to be straightened out.”

“They don’t know how to work,” Jerry roared back. “It’s against the Constitution. They have to be here the right way.”

Listening to the tumult without getting involved was Mark Kuhn, a member of the county board of supervisors. “Very few cows get milked around here without an immigrant,” he told me in a low voice after Jerry had migrated to another part of the bar. “Your average hog farmer out here? He’s a Trump supporter. But he hires immigrants to shovel the manure.”

“How did this happen?” he wondered, sipping a beer. “When did we become such a closed nation?” It’s a question that even reluctant politicians must address. In November, Abby Finkenauer defeated Rod Blum by a convincing margin of more than 16,000 votes. And even though Finkenauer had hardly made immigration a cornerstone of her campaign, Republicans immediately predicted that she’d be a prime target for unseating in 2020. As a headline on Breitbart put it, on the evening of the election: “Mollie Tibbets’ District: Pro-Amnesty, Pro-Sanctuary City Democrat Wins.”

The Farr Side bar is two blocks from where Dvořák had lived. In the months before he came to Spillville, while living in New York, he had invited several black performers to sing tunes for him that had their origin in the plantations of the South, and he incorporated parts of them in his New World Symphony. Dvořák knew that there could be no consideration of the folk music of America without first paying homage to the Negro spiritual; moreover, he believed that American composers had an obligation to draw from this material, just as he had worked rural Bohemian melodies into his own symphonic and chamber works.

While in Spillville, Dvořák indulged his fascination with America’s indigenous people. He went to see a traveling medicine show put on by the Kickapoo Tribe, who played drums and sang in a way he had never heard—the ensemble included two black Americans who incorporated Native American musical elements into their performances on banjo and guitar. He took a side trip to Minneapolis to see the waterfall mentioned in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem “Song of Hiawatha.” He later wrote an article for Harper’s that expounded on the specific style of American music he felt was emerging. “It matters little whether the inspiration for the coming folk songs of America is derived from the Negro melodies, the songs of the creoles, the red man’s chant, or the plaintive ditties of the homesick German or Norwegian,” he wrote. “Undoubtedly the germs of the best in music lie hidden among all the races that are commingled in this great country.”

Within a week of his arrival in Spillville, Dvořák finished the first sketches for his String Quartet in F Major, op. 96, now known as the American. “Thank God!” he wrote at the bottom of the score. “I am content. It was fast.” It received its first performance in private, at the home of Jan Kovařik, the town schoolmaster and father of Dvořák’s secretary.

Music critics have since read all manner of native sounds into the American Quartet. Dvořák was a notoriously democratic sampler, and he never made it clear whether the third movement was supposed to channel a songbird, or if the second movement did indeed incorporate one of the African-American spiritual hymns that he loved. Others have discerned within it the rumble of the Chicago Express train that took him to the Midwest, or the delighted laughter of friends mingling in a country tavern, or a Stephen Foster melody, or the ritual drums of the Kickapoo Tribe. It all blends together without a firm answer. This American Quartet yields whatever its listeners want to hear within it.