Award-winning artist Nekisha Durrett was born and raised in the Washington D.C. area and now teaches at the Duke Ellington School of the Arts. Here, she discusses two of her most recent installations, and how they relate to family memory, nature, and notions of black identity in the 21st century.

“For Then I Wished That I Could Come Back as a Flower, I started thinking about my relationship to the natural world, and one thing that came to mind was my experience hiking. When I go on trails, I am oftentimes the only black person. That led me to consider why it is that the black people that I know don’t have a relationship to nature—basically, the history of black people in outdoor spaces and what that meant for a black person’s safety to be camping in the woods.

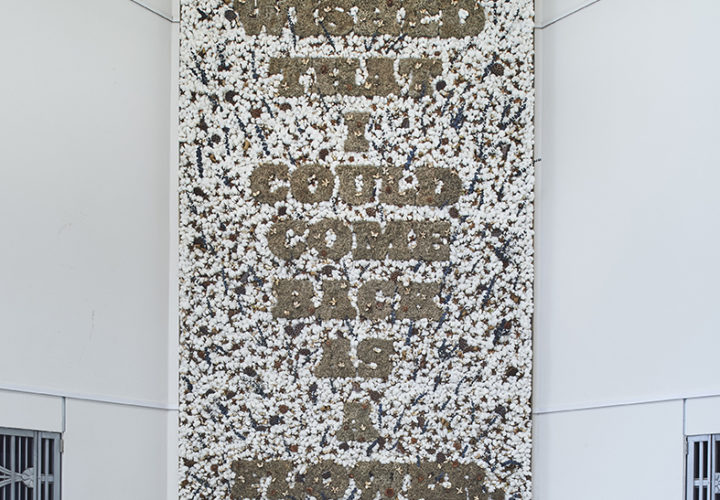

I thought about our history as it relates to cultivation and agriculture, as well. A few years back, I heard an interview on NPR about a book written in the 1970s called The Secret Life of Plants. The book compiled experiments that scientists had done about the sentience of plants—how they could feel and respond to pain, and how plants communicate with one another. So I started reading about these ideas and thinking about what people and plants might have to say to one another. What would that conversation be like? At the same time, I was thinking about black people and our relationship to plants and how certain plants carry a certain meaning. Cotton, for example. All of the images of cotton and black people on Google were of slaves on plantations—awful, painful imagery. These images starkly contrasted with those of white people at Southern weddings, where the décor of choice was cotton bolls and mason jars. In 2017, the president of a university in Tennessee invited members of the Black Student Union over for dinner. He had placed cotton bolls on the table, and the students were horrified. The president hadn’t set out to offend the students, but the resulting controversy revealed the huge divide in how people perceive this one object. That was fascinating to me. If a cotton plant could communicate with the slave picking it, would it say, ‘I wish I could come back as a flower’?

The installation Out of the Blue Black, incorporates more than 20,000 polymer clay clovers. The idea for it came from the discovery of some of my grandmother’s letters and keepsakes after she and my grandfather passed away. My mom found a suitcase, hidden in the back of a closet, filled with things my grandmother had saved since she was a teenager. I went over one day to look through them, and ended up having a conversation with my mom about how my grandmother ended up in upstate New York. My grandmother and her parents originally lived in southern Virginia and moved north because of employment opportunities and general safety. Somehow my great-grandfather found a property in Poughkeepsie. The realtor said, ‘I found you this perfect house, but it’s in a white neighborhood and I can’t guarantee your safety, so you’re going to have to move in at night.’ So they did—they moved into the house at night. This raised so many questions for me. What was that like? How long did they have to stay in this house before they revealed themselves to the community around them? I know they eventually got along well with their neighbors, but how long did it take for that to happen? I think what they did was really brave and hopeful, so I wanted to create a space at the Arlington Arts Center that was a fantastical, magical place that paid tribute to my grandparents. In my grandmother’s suitcase, I had found four-leaf clovers that had been pressed, which was something that I used to do as a kid. I like the visual idea of being carefree enough to go out and pick these clovers and to believe in luck and magic enough to collect a bunch. So I replicated this tiny object thousands of times.”