Sin

“It was enough that I was there, mutely listening as he recited his sorrowful dreams, or spooled out what he called his misgivings, his guilts,

By the last week of April, the parking lot’s long chainlink fence already bristles with its hundreds of attachments: coiled wire, duct tape, butterfly clips, boat hooks, coat hangers, pellets of industrial glue, nylon strips, braided strings, and whatever other contraptions stubborn ingenuity can dream up. Elsewhere, there are the uptown galleries, discreet and sleek as salons, with their Japanese pots on polished lion-pawed tables, and the walls behind them hung with small framed paintings ratified by catalogs signaling critical repute. And of course the grand museums

with their marble stairs and broken-nosed Roman busts in halls mobbed by foreign tourists. —Well, so what and hoity-toity and never mind! With us fence daubers, it’s catch-as-catch-can, whoever happens to pass by, and it’s smelly too, because of the pretzel man’s salty cart on one end of our sidewalk and the soda man’s syrupy cart on the other, and always the sickening exhaust from the cars grumbling every half hour in and out of the parking lot. And the hard rain, coming on without so much as a warning cloud to shut down business for the day, and all of us scrambling to cover our merchandise with plastic sheeting, which anyhow the wind catches up and tangles and carries away, along with someone’s still life.

I call it merchandise. I don’t presume to call it art, though some of it might be, and our customers, or clients, or loitering gawkers, or whatever they are, mostly wouldn’t know the difference. As for us, we’re all sorts—do-it-yourself souvenir peddlers (you can pay a dollar to coat a six-inch plaster Statue of Liberty in silver glitter), or middle-aged Bennington graduates in jeans torn at the knee who speak of having a “flair,” or homeless fakes, soused and stinking and grubbing for coins, who put up pages cut from magazines, or part-time coffee-shop servers self-described as art students. With the exception of the sidewalk chalkers who sprawl on their bellies, indisputably sovereign over their squares of pavement, we are warily territorial. We are all mindful of which piece of fence belongs to whom, and which rusted old folding chair, and who claims the fancier plastic kind swiped from outdoor tables set out by restaurants in the good weather. And there are thieves among us too: if you don’t keep an eye out, half your supplies will disappear, and maybe even your wallet.

I am one of those art students, though it’s been a long while since I stood before an easel staring at a bowl of overripe pears while trying to imagine them as pure color and innate form. This was happening in the Brooklyn studio of my mentor at the time—mentor was his word for it—at a fee of $75 per session. He had a habit of repeating a single, faintly sadistic turn of phrase: what I needed was discipline, he told me, and as my mentor he was naturally obliged (the meanly intended clever laugh came here) to be my tormentor. I had an unhealthy tendency toward literalism, he explained, which it was his responsibility to correct. He regarded himself as a disciple of the legendary Philip Guston, but only in his early period. After three months or so, I couldn’t bring myself to believe in the Platonic souls of pears, and besides, my uncle Joseph in Ohio, who was subsidizing those pears even while under the impression that I was learning fashion illustration, was coming to visit the Avenue A walkup I shared with a Cooper Union engineering student and his girlfriend. Joseph had taken me on as a good deed after my stepfather died. He wasn’t exactly my uncle; he was my stepfather’s brother, and he was proposing, along with attending to some necessary business in New York, to look me up to see how I was doing. I saw then that the flow of money was about to dry up—the money for my tormentor and the money for my half of the rent: the engineering student was soon to graduate and marry and start a job upstate. Within two days Joseph flew back to Cincinnati, betrayed.

“Goddam it, Eva, you’re a goddam orphan,” he threw back at me, “and look at you, cohabiting with a pair of degenerates, and those imbecile oozings piled up in that dump, you’ve played me for a fool—”

He hadn’t believed me when I told him that the study of swirls and random swipes was a prerequisite for fashion design.

Joseph’s sloughing me off left me nervous: fences can’t supply steady cash the way uncles do. Still, I knew I wasn’t meant for the garment industry. Only a year ago I had been blissfully in love with the pre-Raphaelites.

I began to wait tables from seven to midnight at La Bellamonte, an Italian restaurant down the street from the fence. And it was I who carried off two plastic sidewalk chairs, one for the portraitist (this was what we called ourselves), and one for the sitter. It was good to be literal—to work up a reasonable likeness—though not too much. For portraits, a bit of prettying was always preferable. Beginning about May, when the weather warmed up, straight through the middle of October, the money was reliable. I would charge according to how my sitter was dressed, though I was often wrong. I was amazed by the vanity of what I took to be, from the condition of their shoes, the poor: they were willing to pay as much as $5 without giving me an argument, and sometimes I just tore the sheet off the pad and handed it over for free. Of course I sold what I could of the stuff I hung on the fence: these I splashed out quickly, between sitters—fanciful birds on branches, Greek-shaped vases overflowing with flowers (I had a botany book to copy from), invented landscapes, some with mountains, some with lakes. If there were lakes, I sketched in a boat with French lovers in old-fashioned headgear, huge feathered brims for the women and top hats for the men. From the local pharmacy, one of those acres-wide brilliantly lit warehouses where you could find anything from cheese crackers to lampshades, I bought cheap wood frames and painted them white. This gave the pictures on my three yards of fence almost a look of settled elegance.

Weekends, Sundays especially, are our busiest time, when people stroll by with their sodas or dripping popsicles (there’s an ice cream vendor one block over) to watch the portraitists at work. For onlookers like ours, a portrait is an event requiring the courage to decide which of us to choose, and a certain daring even to submit to a 20-minute sitting, surrounded by all the public kibbitzers who comment on the process, whether this person’s nose is really wider than it’s been shown, or taking note of a wattle that’s been brushed away. Generally the crowd works itself up into a mood of untamed but not unfriendly hilarity. Yet sometimes it will be cruel.

It was cruel to the woman in the blue suit. She was not unfamiliar. I had spotted her yet again when, on the third Sunday in a row, she turned up, gaping with all the others circling round my easel. The weather was unusually hot for a late August afternoon coming on toward evening, and the baking pavement, with its crackle of pretzel crumbs, was still burning the feet of the pigeons; they were hopping more than pecking. Or else they were sated. As for me, I’d already counted $152, more than enough for a single day’s work, and was beginning to pack up the little it was my habit to take away for the night—brushes, paints, botany book, easel (the folding kind). The paintings I would leave where they were. I threw a worn tarp (pilfered from a car in the lot) over my part of the fence and with a piece of narrow rope knotted it through the gaps in the steel. What if rowdies came and ran off with my landscapes and flowers and boats? I would deem it a compliment, and anyhow I could readily splash out a few more.

By now many of the gawkers had dispersed, and the pretzel and soda men were long gone. But the diehards were still milling on the sidewalk, with bottles in paper bags bulging from hips and armpits. The woman in the blue suit was among them, cautious, attentive. Watchful.

As I was maneuvering the easel into its carrier, she called out, “Not yet, not yet!”

“Sorry,” I said, “I’m just leaving, I can’t be late.”

“Why should I care, I’ll take my turn now. I don’t like it with that riffraff all around. So now.”

“Sorry,” I said again. “I’ve seen you before, haven’t I? Then maybe next time? Or instead”—I lifted an edge of the tarp—“you could take home one of these, I’d let you have this one for half the price. A scene on the water.” It was the feathered brim and the top hat.

“I don’t want that kitsch. I want you at the easel. I want to see up close how you do it. I know what I want.” This hint of disputation drew the diehards. Some of them already had the mouths of the bottles in their mouths. “All you people, get out of my way. Scum!”

Here was authority. And authority was money. The austere blue suit, of some summery fabric I couldn’t name, the lapis necklace, the crucial absence of earrings, the gold loops on her wrists, and especially the tiny laced shoes, of that blue called midnight. Oddly small feet, a tidy head on a thin neck—she was small all over. Voice an uncontained ferocity. She looked to be—she could easily have been—a regular at the uptown galleries. And with her surliness she had mocked the surliest remnant of the crowd.

They mocked back. They called her cross-eyed (this she was, very slightly), they laughed at her skinny neck and her little feet, they laughed at me for surrendering to her whim. Once again I set up the easel. She took her place on one of the plastic chairs with an angry stubbornness that soon became a barrier. My own chair I had shoved aside; if I stood, I might dominate. Her face, I thought, had traces of insult, the eyelids tightened at the outer corners. How old was this woman? A portraitist, even my sort of sidewalk quick-job, relies on age; it animates character. But her fixed stare, guiding the brush and judging its pacings, gave out nothing. I bent closer to see the color of her irises. In the lessening light they had a yellow tint.

“Stop ogling,” she spat out, “just get on with it, I’m not sitting here all night—”

The sun was dropping behind the parking lot. The last of the hecklers, finally bored, dwindled and scattered. I hurried to finish, forsaking detail, drizzling a mist of hair of indeterminate tone (was it brown, was it gray?), and privately calculated my price. The woman in the blue suit was rich; she had money. Rich people have good clothes, nice shoes, fine teeth. My uncle Joseph had paid thousands for his implants. On the other hand, this woman had sought out a street painter at a parking lot fence, so perhaps she was no different from the forlorn in their rotted sandals … yet how could this be? Her insistence had the brittle scrape of worldliness. She was a force. I lifted the sheet from the easel and held it out to her.

“Look at that thing, what would I want with that? It’s the hand I’m after, I told you, seeing it up close, the grip, that little bit of hesitation just after—”

She snatched up her likeness—I’d caught her well enough, that angry lower lip, those inharmonious eyes—and tore it in two.

I said, “You have to pay anyway, I’ve done the work, you have to pay.”

She drew from a flap of the blue suit a tiny blue purse. “Here, take this”—it was four hundred-dollar bills—“and there could be more. Does Sol Kerchek mean anything nowadays? I didn’t think it would, you’re too young.”

I contemplated the name: nothing. I contemplated her money. It was still in her grasp.

“He’s ancient history, people don’t remember. I had someone all picked out last month, a boy, I found him crouched in a corner so the guard wouldn’t see. He was copying a Klimt. But in the end, he was no good. He had the hand, but the whole thing was over his head. So,” she said, “are you taking these or not?”

She wiggled the four bills under my chin. The engineer and his girlfriend, I knew, were already packing their belongings. In a few days they’d be gone, and my rent would instantly double.

“In the beginning,” she pushed on, “you’d only have to clean brushes and so on, keep the place from getting overrun with rags. After that it’s all up to him, whatever he wants.”

“I’ve got a job, I don’t have time for another—”

But already I saw that La Bellamonte would not soon claim me again.

She gave me that askew look; there was triumph in it.

“You don’t have time for Sol Kerchek? You don’t have time for a man whose work sits in Prague, in Berlin, in Kraków? In London? Those were the old days, but he’s not dead yet, he’s worth something. You should get on your knees for the privilege, you don’t deserve what I’m offering—”

I shot back: “You ripped up my work, you called my stuff kitsch!”

“I say what I say, and I see what I see.” She stuffed the bills into the pocket of my shirt. “Come on, it’s only a 10-minute walk from here.”

I followed her then, threading through the gathering evening crowds on the sidewalks, past the red and green neon blinks of bars and suspect dance halls, past newsstands hung with key chains and caps and sunglasses, past check-cashing storefronts, bauble vendors, boys handing out flyers for fortune tellers. The air was seeded with the fumes of lemony hookahs, and from the open doors of a row of ill-lit cafés, many with insolent old awnings, came the whine of guitars and a scattered pattern of clapping. We were coming now into darkened streets lined with tall silent after-hours glass-coated office buildings. A few windows were randomly lit.

“This is his place,” the woman in the blue suit said. Between a pair of these giant vitrines stood a small clapboard house with a high stoop. Part of the siding was covered with stucco; the stucco showed meandering cracks, barely visible in the glow of the street lamp. Crushed by the brutes on either flank, the little house seemed to quiver with its own insufficiency.

“We put in a skylight a few years ago, but with the way his eyes are now, there’s no point, all that construction debris and birdshit and whatnot, even the sun can’t push through. And these monoliths they put up, there’s no light anyhow. They tried to bribe us to sell, that’s how they do it, but he wouldn’t give in, it’s like that with the old. Well look, here’s something convenient.”

I saw a concrete city trash bin.

She grabbed my easel—I had been carrying it tilted over my shoulder, like a rifle—and tossed it in. The plastic carrier tore with a screech.

“You won’t need that anymore. There’s a better one upstairs.”

I trailed her up the eight steps of the stoop, denuded.

“It’s these steps,” she said. “He never goes out. And then the staircase going up, it’s too much.”

In the vestibule, an abrupt patter of foreign voices. The smell of something frying. Sol, she told me, had the apartment at the top. The whole place, from end to end, was his studio. The people on the lower floor were a Filipino couple, the man ailing; only the woman mattered, she brought Sol his dinner every night, she cleaned his awful toilet, she changed his sheets. I wouldn’t have to do anything like that, she assured me. Maybe now and then I could boil water for his tea, find him a cracker to go with it. My responsibility was solely to his art, did I understand?

I asked about the hours and the money.

“The hours are whatever he says, whatever he wants. And let me worry about the money.”

She showed me what I took to be a business card and then pinched it away. I had only a moment to see Mara Kerchek, Consultant, and a row of digits below.

“He won’t have a phone, he doesn’t like to be bothered, he says he can’t hear. If you think you might want me, you can text me.”

“I can’t,” I admitted. “Someone swiped my phone. Nothing’s safe at that fence—”

“Oh fine, incommunicado, the blind leading the blind. Go get yourself a new one.” It was a command. “Not that you’ll ever want me up there.”

Mara Kerchek. So the old man must be her father. His door, a heavy thing with carved scrolls, was half open. A relic purloined from some nobler house.

“Sol!” she called. “I’ve got someone.”

I had expected him to be small, like Mara Kerchek. He was stooped, with the bony spikes of massive shoulders leading down to a pair of uncommonly large and dirty hands. Every fingernail carried its load of dried paint, mostly blackened. A wayward white thicket smothered his big head, and around it a hint, even a halo, of hugeness, like a ghost of the mountain he must once have been. The fuzz on his slippers was trembling.

“Mara, Mara!” With tentative balance he tipped forward to embrace her, and I saw that his eyes, droop-lidded and milky pale and full of sleep, were emphatically unlike hers. She let him hold out those monstrous hands long enough for a single heave of his breath—ponderous, sluggish—and then patted them away. Or was it a mild slap?

“My little Mara,” he said. “All in blue, all in blue, look how beautifully she dresses, she’s always dressed that way, she knows how to do it, she always knew, even at the start—”

But she cut him off. “He likes to talk a lot, don’t you, Sol? You don’t have to listen,” she told me. “And he won’t use his cane. The way he moves, make sure he uses his cane.”

The little blue shoes quick-tapped down the stairs.

“She indulges me, you saw that.” He was looking me over with, I felt, a dubious fastidiousness. “Last time it was that boy, couldn’t tell his left from his right. But she means to please me, she has a merciful heart.”

“She was in a hurry to get away,” I said.

“She has her work.”

Under the muddy skylight (it was night now), I took in a scene of stasis. Stillness and disuse. A tall thick-legged tripod, naked and faceless as a skeleton, and near it a low table littered with dozens of dried-out paint pots and a jar of hideous brushes, heavy and stiffened. A four-footed cane hooked over a battered wooden chair. The dusky room itself as long and narrow as some corridor in a gloomy hotel. At the far end I made out a pair of dirty windows—dirty even in the dark. And when I switched on the only lamps I could discover—all three had torn silk shades—the cluttered walls on either side of Kerchek’s studio (it was Mara Kerchek who had named it that) bluntly revealed what I had caught sight of but hadn’t accounted for. Those lumpy silhouettes were canvases, masses of canvases stacked back to back, wild and unframed, flaming, stricken with a crisis of color, the paint as dense as if sculpted.

And between the walls, a chaise longue, tattered only a little, dangling crimson tassels over curly squat feet, islanded in the void under the blinded skylight. All around, a public smell—the smell of Kerchek’s toilet. It drifted from space to space, mingling, I imagined, with the fetid odors of worn and crippling age. It was clear that the woman in the apartment below was negligent; the care of the toilet, and the abhorrent hollow of the grubby cubicle that was Kerchek’s kitchen, and the jungly bed I glimpsed in the dim hollow behind it, would fall to me, and what was I, why was I here? If sometimes the woman below failed to turn up with his meal, would I be obliged to forage in some nearby midnight diner for whatever might pass for Sol Kerchek’s supper?

I got rid of the decaying brushes and filled the jar with my own. I made some small order in the sticky kitchen. I gathered up armfuls of paint-soaked oily rags furry with dust—the accumulation of years—and tossed them into the city’s trash bin; my easel was gone. From under Kerchek’s bed I pulled out a a roll of canvas grayed by grime, and a torn cardboard box heaped with stale tubes of oils. I twisted one open; out sputtered a clot of brilliant turquoise.

And all the while the four-footed cane still hung disobediently from the wooden chair. Mara Kerchek had snapped out an order; Kerchek refused it. Then why shouldn’t I defy Mara Kerchek, why must I satisfy Mara Kerchek? What would I do with a phone in this timeless feral place, where an old man’s breathings were measured only by a faraway sun moving languidly across an opaque skylight? Here was freedom, and leisure, and unexpected ease. My wages, delivered by the woman below, sometimes came, and sometimes did not, and always in the shape of hundred-dollar bills sealed in an envelope coiled in masses of tape, its thickness impossible to predict. One envelope might be skimpy, the next one fat. I was content; ever since my uncle Joseph had given up on me, I had never felt so flush. Mara Kerchek herself kept away.

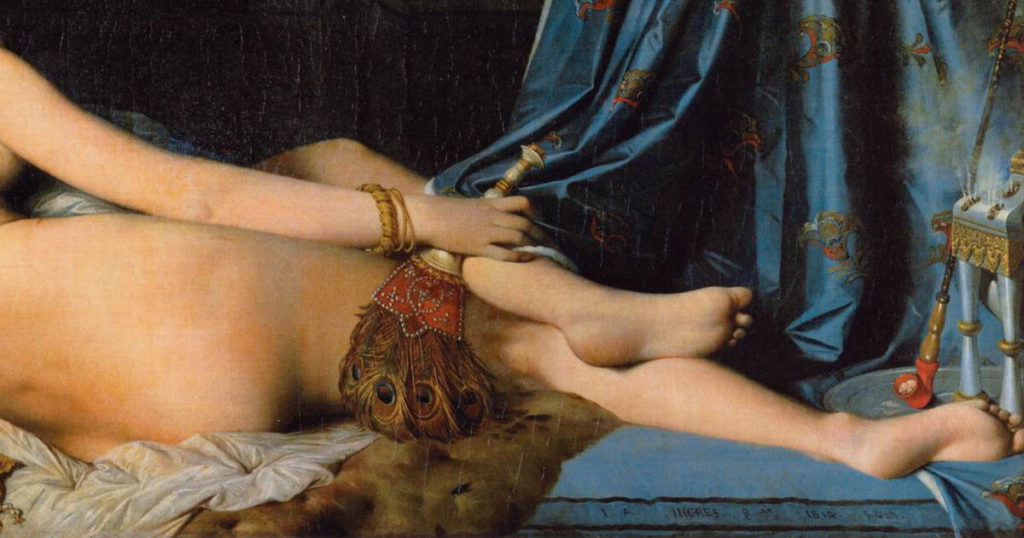

In the afternoons, it was Kerchek’s habit to totter, caneless, toward that grotesquely ornamental object under the skylight, where he dropped into a doze. He lay there among its royal cushions like some misshapen odalisque, dozing and waking, dozing and waking, and soon enough he would shudder, hotly aware, into an excited cry, a remnant of some dream. His dreams, he told me, were omens and alarms—catastrophic, shaming. And more than once he explained how this misplaced Oriental curiosity came to flutter its fringes between the walls.

“My paradise, my sanctum,” he said. “Look how my Mara indulges me. She found this marvel, who knows where she picked it up, she finds me everything, she found me that door, she found me that boy who didn’t know his left hand from his right hand, she found me you, and do you know why? My foolish little Mara believes in instinct. She believes in resurrection. It’s all mumbo jumbo. Superstition.”

His voice puzzled me. Ingratiating, taunting, as if it concealed a fear.

In those early weeks, in the empty hours when Kerchek clung to his divan, and at other times too, I might easily have wandered off into the city streets on musings of my own, or walked the halls of the great museums uptown, where the world’s imagination was stored. Instead, I searched out a pastry shop tucked among those glassed-in office buildings, and went every day to buy muffins and little cakes and canisters of foreign teas and blocks of oddly colored cheeses to fill Kerchek’s blighted cupboard. And once, in a half-hidden alley, I blundered into a lively bodega, and returned with eggs and onions and potatoes and a bit of fish. In the evening, if the woman below brought up a soup that was too thin, or dry chicken parts more bone than flesh, I would cook up a stew or fry an egg. He was indifferent to my comings and goings. It was enough that I was there, to sit with him over teacups, mutely listening as he recited his sorrowful dreams, or spooled out what he called his misgivings, his guilts, his remorse.

“In those days,” he always began, and then he would speak of the time before the war, and what war was that? All those wars, how was I to know, was it a war before I was born, or after? Why was I here, what was I meant to do?

The skylight was turning autumnal.

“Eva.” He rasped this out with a lordliness that surprised me. After so many muffins and little pink cakes and cups of tea—after so many rueful mutterings—it was the first time he had spoken my name. Then he asked how old I was.

“I can’t tell from your face. My eye can’t see eyes. Faces gone, color no, my Mara in blue—” All this staccato, like gunshot.

I told him I was 23. But I put my head down. To admit to this meagerness was a humiliation. Mara Kerchek had already parsed it: how could I deserve to be in this place with an old man’s spiraling regrets, when I had none at all?

“Well, so much for that. My little Mara was 26 when we started, and how ambitious she was! And how cleverly she dressed even then, the way she carried herself, it gave her entry, you know, to the galleries, they saw her belief, they took on her belief—”

He stopped to attend to one of his slowly toiling breaths. I watched his torso, bent as it was, climb and recede, climb and recede.

“She hawked my work. After a while they came to her from everywhere. She made us rich. Never mind that she exaggerates, she lies a little, she indulges me, she makes you think Louvre, she makes you think Prado, it was nothing like that, but in those days,” and he returned again to the time before the war, when his paintings were coveted, when his name was coveted, when there was everything all at once, everything newborn, a gluttony for the never before, schools and movements and trends and solemn revolutions, the orphists, the purists, the futurists, the vorticists, and soon the action painters, he was with it all, in the swim, in the maelstrom of all that delirium, and it was easy for Mara to make them rich. Especially during his divanist period (this was Mara’s flourish), his conceptual nudes, his minimalist nudes, his spatter nudes, all of them parting their legs on sprawling velvet couches.

And sometimes, he told me, it was Mara who posed naked for him on that cheap chaise longue they’d bought, in those days, right out of the Sears, Roebuck catalog.

I asked if Mara would come, if he expected her to come.

“She keeps away,” I said.

“She has her work. It wears her out.”

He stared me down with his milky eyes. Untamed wads of hair spilled over his collarbones. And again that stale aurora of things long eclipsed, those old grievances, if that’s what they were, unfurling hour after hour, the same, the same. And then again the same. The spittle on his lip when he scraped out yet another weighty breath. He looked, I thought, like someone’s abandoned messiah.

“My Mara is estranged,” he said. “I’ve disappointed her, I haven’t been good to her. She made us rich, I made her poor. After the war I made her poor.”

Poor? The lapis pendant, the gold bracelets, the perfected blue shoes with their satin laces, the silken blue suit (was it silk, was it something else), the hundred-dollar bills?

I asked him if he would allow me to trim his hair.

His mind was all Mara. Mara, Mara, my little Mara. And wasn’t I his echo? Daughter, father, banished words, useless here. Only Mara, Mara.

“She has a merciful heart,” he said, “she indulges me, but still she casts me out, she doesn’t relent. Year after year, after the war.”

He told me where I might find a scissors—under the dirty windows, at the far end of his studio, beyond the skylight, in the deep drawers of a tall corner cabinet. The scissors was there, and a hammer and a vial of small black nails, and a roll of new canvas, and a sack of fresh tubes of oils. And a crisscross of stretcher bars. Mara, he explained, had ordered that boy to bring in all these useless things, that boy who didn’t know his left hand from his right hand, and what good was any of it anyhow?

“The eye is the hand,” he said. “And without the eye, the hand is as good as dead.”

Shards of hair flew to the floor. I bent over him to do away with the tangled woolly forelock, and then his head was close against me, and I could feel in my ribs the heat of his history as he wove and unwove the knit of what was, how with all his generation of men (but he was older than most) he had been made to go to that faraway war, first in a massive ship, and then the landing on a blasphemous continent, its cities of slaughter, its trenches and shootings, planes like fleas in the sky, men who were wolves to men, women who covered their breasts with their hands, human flesh smoldering, and he saw and he saw and he saw, and he knew and he knew and he knew, and what he knew was that the body of the earth is cut in two by a ditch. A ditch between two walls.

But I had worked too close to the scalp. There was little left to cover the violated head. It was as if I had excavated a skull.

“In those days,” he went on, “when the war was finished, when the war had evaporated, everything swept back to before, again the new, the new,” and he told of the new office buildings, the new neighborhoods, the new hem lengths, the new markets, the galleries hungry for buyers, the collectors hungry for prestige, the contractors hungry to dazzle their suites, and oh how Mara believed! She assured him that he had only to resume. He was older than most, he was weary, he’d come out alive from the precincts of sin, and why, he asked, must he resume? She knew exactly, she was impatient to begin, she was inspired, the newest thing wasn’t the newest thing, the newest thing was the oldest thing, she had been gazing, gazing, walking the Guggenheim, walking MOMA, in library reading rooms paging through catechisms of paintings, their periods, their masters, they fed her instincts, she had the clairvoyance of her instincts, and she hummed out the names of the old divanists, the old luxuriant gods, Modigliani, Matisse, Delacroix, Morisot, even Millet, even Boldini, divanists all, and more and more! She was in the thick of things, she was in the know, she could scent what the market craved, what it ought to crave, what she would teach it to crave, what the collectors devoured.

It was naked women lying down.

“She wanted me to go back to the divans. She wanted me to remake them in the shapes of all the new crazes, dance to the new tunes, old profits in new clothes, all her contacts were waiting, all her old clients, all those rich men looking for the latest thing. Retrofit, assemble, usurp, they could call it any fool name they liked, it was divans, divans, and what else was it but my Mara undressed and lying down? Still,” he said, “look around, look around, and tell me if I haven’t repented—”

He drilled a thick finger with its thickened fingernail through the darkening air, as if it could span the ditch between the walls, where, on either side, those heaps of canvases leaned moribund in the dust. The woman below came with his evening meal. The soup was again thin. He spooned it up and sent the rest away. Already, for many days, he had spurned the cheeses, the muffins, the little pink cakes; but he went on warming his hands on his teacup. I no longer sought out the pastry shop; it sickened him. The bodega, hidden in its alley, had anyhow failed. He took to using his cane.

In late November a peculiar brightness fell. Overhead, soundless cushions folding and unfolding: it had snowed in the night. The burdened skylight, soaked in sun, poured down rivers of white. The light, the light!

I asked if I might turn the canvases to the light.

“She couldn’t move a single one,” he said. “Not a one. The bleedings of three years, when I still had the eye, when I still had the hand. She begged for the divans. Instead I gave her these. Go turn them if you want, but I warn you, I warn you—”

I saw how heavily he lowered his big shoulder bones and the warp of his spine into the wooden chair where the cane had been shunned; but now he cherished it. And in an instant of shame I regretted cutting his hair. There was nothing to conceal his meaning. His meaning was transgression. He sat like a witness. It was, I felt, a vigil. Or a rite. A judgment. The vacant tripod stood nearby.

In that unnatural snowy light—or because of it, because it illumined the shadowy walls with unaccustomed clarity—I was at liberty to turn and turn each canvas, to see into this one, to inhabit that one, even to be repelled by all of them. To be warned and judged and sentenced. I saw how they were afflicted by a largeness. Even the smallest conveyed a looming. I saw what I imagined to be scenes, a ferryboat overturned, fires ingesting whole towns, drownings, earthquakes, scorching lava—but almost immediately I knew these to be illusions, the tricks of color and form and the impulsive licks of the brush. The tricks of largeness, of appetite for ruin. I thought of the scored palms of Kerchek’s elephantine hands.

I crossed from wall to wall. Between these frenzies a ditch. Smoke, seared flesh, anguish, trains, engines, silent explosions. Yet hadn’t he warned me? I was not to do what that ignorant boy had done, the boy who didn’t know his left hand from his right hand. I was not to mistake a canvas on the left wall for a canvas on the right wall. I was not to misplace, I was not to compare. They were distinct, one wall from the other. And mutually alien: each an enemy to its opposite. Each wall was an archive. Each wall was a clamor. Each wall was a shriek. Right wall was at war with left wall.

These, he told me, were his repudiations, his repentance. In those days, when he still had his eye and his hand, they had the power to redeem. And now they festered.

“Mara couldn’t place any of them,” he said. “They weren’t wanted. She didn’t understand any of it, she didn’t expect anyone to understand, she wanted the divans, she wanted the profits, they were there for the plucking, the postwar markets all on fire, why was I scheming to make her poor, was it vengeance?”

The sun had passed over the skylight. Kerchek’s studio—how forlorn it was—returned to its daytime dusk. The canvases were again what they had been: dead things decaying. In a hidden corner of each of them, an obscure sign: SK, intertwined like an ampersand.

I confessed that I could see no breach between one wall and the other. The wall on the right seemed no different from the wall on the left.

“You don’t see, you don’t see? You with your eyes, you can’t see? It was Mara, my Mara, who made me see—”

I waited while he searched for his breath; I had learned to wait. A little snake of a laugh crept out of his throat. It frightened me; it meant he was waning. His afternoon dozes had grown longer and longer. I had cut his hair too close to the scalp, his head was naked, and what if he died before Mara came, what was I to do? And when would she come?

It was Mara herself, the joke of it, he told me, who drove him on, who drove him into the work of the walls, if not for Mara he might have succumbed to the divans, scores of divans, hundreds of divans, seduced by the schools, the movements, the profits, the old made new. If not for Mara, after the war. She came to him, straight out, or how would he know to tell it now? An inchling, she called it, she did away with it, what else could she do, it was only an inchling, a pinch of fat in the womb, so why did it matter? His poor little ambitious Mara, hoping to lure her clients, her collectors, to please, to appease. Even then, even then.

And that discarded pinch of fat in the womb, was it the same as the poisonous brown seed of the apple, and if you crush the seed, you give the lie to the tree? Was it the same as the capsized ferry and its drownings? Was it the same as the bridge that collapses from age? Or the floods when the tide comes in, or the fires the winds ignite? Is the inferno in the belly of the earth the same as sin? Or the fever that kills? Is the river that dries no different from will? Who dares to fuse the two? Only a pinch of fat in the womb, so why must it matter?

“But I wept, you know,” he said. “I wept. And then, because nothing mattered, not even a pinch of fat in the womb, I began to see again. I saw with all the strength of my body. Sin on one side, calamity on the other, with a ditch to keep them apart. Only men sin. Only women. It’s an innocent God who wakens ruin.”

I can’t say that these were Kerchek’s words. I can only say that this is what I heard. After all, he never spoke of God. He never mentioned sin, and hadn’t he sneered at superstition? In fact, I remember that he said very little, only that once, long ago, while up to his knees in running blood on that blasphemous continent, Mara Kerchek conceived a child and did away with it.

And afterward—after letting out this small note—he went on dabbling his spoon in his soup.

The next day all that was forgotten. He warmed his hands on his morning tea and asked me plainly if I knew why Mara Kerchek had brought me to him.

“To be your assistant,” I said. What else should I say?

“Did she do her hocus pocus? Put you up for trial? My silly Mara with her sixth sense—”

“She called my work kitsch. She tore it up.”

“Eva,” he said, “come here. Give me your hand.”

It startled me to hear him speak my name yet again; it seemed almost conspiratorial. I placed my left hand on his right hand. It lay there like a small salamander nestled among the mounds of his knuckles.

“Hocus pocus,” he said. “Abracadabra. She means to make it all come back to life. And do you know why?”

I had no answer. I feared his confidings, I feared his trust. If he was dying—the skin of his head was pitted and rusted and crumpled—if he was beginning to die, it wasn’t for me to give him deliverance. He had a daughter for that.

“My Mara is sick of her work, it wears her out, I haven’t been good to her. I’ve brought her down, I’ve made her poor—”

It was his usual chant. I thought I would tear through it outright.

I said, “Mara’s work, what is it?”

“The same. Always the same. The clients, the consultations, the appraisals. These collectors, they want to possess but they don’t know what they want to possess. She takes them around and shows them. Or else she goes up to their palaces, their penthouses, whatever they call them, to appraise what they already possess. The richer they are, the more they want to spell out the worth of things. The price. They’re cautious, you know, so they pay in raw cash—”

Where was his breath? He was panting a little, a shallow gasp, and then another. A bit of a noise to go with it, and while I waited for the noise to subside, and for his breath to return, it came to me—how open it was—that Mara Kerchek in her silky blue suit, with her lapis necklace and satin shoes, was a woman of the night.

In early December the day gave way to dark in seconds. The lamps were switched on before three, and Kerchek slept on, hour after hour, through the afternoon gloom. His feet, with their slippers fallen, overflowed the divan; the toenails tall and thick and jagged. The head on the ornate cushion a pallid dome. The soft ears uncovered. A remnant of biscuit left uneaten.

From the cabinet under the far windows I retrieved the scissors, the hammer, the vial of tacks. Out of the web of stretcher bars I chose four. I cut a length of fresh canvas, and hammered the bars into a precise fir square. I drew the canvas as taut as could be and tapped it down until it resisted the lightest dent of a fingertip. Then I snipped off the last wavering threads.

Through all this commotion I was vigilant. I kept watch over Kerchek’s breast: was it rising and descending, was this wasted old man breathing? Was he deaf to the hammering? But he slept on. The pale canvas in its frame, resting now on the lip of the tripod, had the look of the white of an eye awaiting its pupil.

And meanwhile in these short December days that rush into night, the skylight turns biblical. Snow falls again, and then again, the wintry wind arouses the sun: let there be light! But the light is theatrical and brief, and must be made much of while it lasts.

It was in just such a snowstruck radiant interval, when Kerchek refused his dry biscuit and took up his cane and shed his slippers and let himself warily down into those velvety cushions to revisit his dreams (but the itch to reveal them had lately weakened), that I began to paint the divan. The divan overflowing with Kerchek.

I painted him slyly, slowly, thickly, hugely, with a raptness new to my hand. I painted his collarbones, the bare ruined pallor of his heels. I painted, with pity, his hands. I painted his looted head, the flattened mouth, the wrinkled ovals of his shuttered eyes. The ways of the fence, speed and slapdash, all for the money, were wicked here.

And I painted the divan, the velvet, the crimson, the cushions, the curly squat legs, the kingly tassels. For 10 days I painted until it was too dark to see. I emptied the tubes of their greens and reds and yellows and taupes, and thickened and thinned them to grow into skin and weave and the gray of veins and the delusions of sleep: a vessel for Kerchek’s mind. I knew what was in it. Dread and pity for such a daughter. Intoxicated by such a daughter.

The woman below stopped coming. It was pointless, he turned away. How I regretted cutting his hair, unclean, even savage. I had meant it for his dignity. Instead it left the bones of his face jutting. I painted them as if they were the crumbling bones of a pharaoh. And it was with something like reverence that I painted the divan: its sultan’s cushions, its swaying tassels, its regally curlicued feet. Soon he would die there, I thought, on Mara Kerchek’s divan.

The skylight’s snow ebbed, the sun hid itself. The light was gone. A wind sent in the cold. The skin of Kerchek’s hands, how like a membrane of thinnest isinglass, and under it the wormy dying veins. I covered his shoulders and arms with a blanket. He had no one to warm him. Mara kept away.

It was enough. Why was I here? The thing was finished.

“I’m going now, I have to go,” I said, and looked down on him. “Mara will come,” I told him. “Any day now she’ll come.”

He didn’t wake. He didn’t hear. I left him and went back to see what I had made. The figure on the divan, was it Kerchek? The resemblance was poor, who would know him? A heap of wornout passion. An unforgiven seer. The traitor father of a traitor daughter.

But the thing was done. Or almost. I picked up the brush with the slenderest tip and in a hidden fold of the canvas painted a tiny emblem: SK. It looked like an ampersand.

“Eva,” he called. A voice hollowed by a stranded dream. “Eva, come here, I’m cold—”

His milky eyes were on guard. He took my hand, but this time he held me by the wrist and passed his heavy fingers over the palm. I felt how coarse they were.

“Do you have a mother? A father?”

“A stepfather, but he died.”

“A child’s hand. Small, like Mara’s. She sees things in the fold of a thumb, in the turn of a crease.” His fingers hardened on mine, one by one. “Mumbo jumbo, my Mara sees, she sees what she wants to see—”

It fell out like a plea.

“No,” I said, “It’s her father who sees.”

“Mara? Mara’s father is dead.”

Was he a man condemning himself? Was it a sentence? A punishment? For the sin of making Mara poor.

“No, no, your daughter has a merciful heart, you say this yourself, she’s bound to come soon—”

“My daughter? I have no daughter.”

Was he grieving, was he lost? Or was it shame?

“You have Mara,” I said.

I saw him let down his legs. I saw him pull himself up from the divan. The crimson tassels swung. His old man’s head shook.

“What are you saying? I have no child, I have no daughter.”

I said again, “You have Mara.”

“Mara, Mara.” His throat thickened. His eyes blackened into char. He threw off his grip on my wrist. “Is that what you think? Is that what you believe? Who told you such blasphemy? That I am the man who would uncover his own daughter’s nakedness, that I am the father who would stretch out his daughter on a couch only to gaze on her lineaments? That I would oblige her to raise her hip for the curl of its arch, that I would beg her to part her thighs, and all for the sake of painter’s gold? Ignorant girl, you don’t know your left hand from your right hand, Mara is my wife, my little Mara, my wife, my wife—”

I can’t say that these were Kerchek’s words. I can only say that this was what I heard.

He sank back into the cushions. I saw his breast climb and recede, climb and recede.

“I have to go now,” I said. “I can’t stay,” and left him there. Someone would find him. The woman below would find him. Or Mara would come.

Well, I’m back at La Bellamonte. Guido, the manager, gives me a second chance, he says, on condition that I never again walk out on the job. As penalty, he’s taken $5 off my old wages. What with the rent on my place, I can barely afford a new phone. Anyhow I’ve bought one. Who nowadays can live without such a thing? I’ve got a new shirt, too, with a zippered pocket to keep it safe. As for the rent, I was lucky enough to scout out a pair of art students from Cooper Union, to pay for half—Richard and Robert. They’re focused and ambitious. Richard is heading for theater design, Robert for advertising. Like the engineer and his girlfriend, they sleep in one bed, mouth to mouth.

When the weather warms up, I’ll go back to the fence. I won’t do landscapes or seascapes or period lovers or flowers in vases or any of that sort of kitsch. I won’t put anything up on the fence. I’ll have a little table, the folding kind, and I’ll filch a couple of chairs when Guido isn’t looking, and what I’ll do is miniatures. On fingernails, female and male. The women generally like ladies in long gowns. The men want snakes and daggers and girls’ names circled in roses, the things you see tattooed on their biceps. All that, I’m told, is the newest craze down there at the fence, and brings in the money.