The Crisis of University Research

Academia’s pursuit of corporate and government dollars has undermined its commitment to learning

The debate over the role of research in the life of the university was settled a long time ago. In a classic 1852 book, The Idea of a University, the Catholic priest and future cardinal John Henry Newman made what in retrospect appears to have been a last stand against the proposition that research should be an intrinsic part of university life. The Newman argument went something like this: if university professors are properly doing their work—seriously keeping up with the reading in their fields, preparing and revising lectures, grading exams and papers, engaging broadly in the life of the university, and guiding students in the decisions they must make at such a crucial time in their lives—then they are not going to produce original scholarship on top of everything else. To Newman, teaching and research were fundamentally incompatible activities, requiring very different talents and skills. Because universities are teaching institutions, research can have no proper business in them. Research, he concluded, should take place in institutes created for that purpose.

Newman was on the losing side of the argument about university research. The great 19th-century historian Leopold von Ranke energetically countered the kind of arguments put forward by Newman, asserting that in his field the capacity to produce and publish original archival research was the real measure of a scholar. Primary sources found in archives were for Ranke the premier form of reputable historical evidence. Young historians in German universities would be trained in seminars to investigate archives. Ranke’s relentless emphasis on the primacy of such research produced a revolution in historiography, and the modern scholarly community of historians is to a large extent a reflection of his wishes for the profession. Scholarship in the university generally came to abide by the spirit of Ranke’s principle that the production of original research determined the professional worth and standing of an institution of higher learning.

For historians especially, the German research university served as the model for graduate programs in the United States, beginning in the 1880s at Johns Hopkins. Historians in America thereafter underwent a rigorous graduate school apprenticeship. An elaborate testing structure evolved, featuring oral and written examinations, foreign language qualifying examinations, and theses and dissertations—leading to the doctorate in philosophy, a German degree. By about 1900, the PhD had become the highest badge of professional competence in American universities. The academic world of conferences, papers, publications, scholarly periodicals, and book reviews took shape in this period. The university as we know it today is a direct consequence of the late-19th-century professionalization revolution associated with Ranke’s name.

Ranke’s model of historical scholarship, however, is not without difficulties. Some of Newman’s concerns about the burden of fully carrying out the responsibilities of teaching, service, and research seem legitimate to many critics inside and outside university circles. Publishing more and more about less and less, the disappearance of grand narrative history, and the loss of a public audience for academic scholarship have been some of the consequences of Ranke’s influence.

The problems of Ranke’s approach notwithstanding, I take his part against Newman on the question of university research. Jaroslav Pelikan, the late Yale University historian of religion and a fervent admirer of Newman, spoke here at the University of Montana several years after publishing The Idea of the University: A Reexamination (1992). He told us that Newman’s eloquent defense of the humanistic tradition was the most profound book ever written about higher education. Newman’s adamantly argued distinction between the liberal education he admired, for the formation of taste and judgment, and what he called servile education, or job training, would always be a rallying cry for real universities. Nevertheless, Newman was wrong on the issue of university research, Pelikan contended. He thought that research and teaching were mutually reinforcing. As lectures are being prepared, important research projects can come to light by a teacher’s discovery of gaps in the scholarly literature on a given subject. Moreover, the mental exercise acquired through research gives intellectual tone to a teacher’s classroom presentations. In other words, the Rankean formula deserves to hold its place as the gold standard for professional life at the university. I agree with Pelikan.

The intellectual integrity of university research, however, is today beset with difficulties caused by corporate and government pressures on the schools. To survive, research universities need the money that only corporations and government can bestow in sufficient amounts. Such patrons as these are not in business for artistic and intellectual aims alone. They have ulterior motives for granting research support to scholars and scientists, with the unavoidable result that the ensuing work bears the mark of its extra-intellectual parentage. Newman’s concerns about university research, significant as they are in scholarly terms, have been superseded or at least dramatically supplemented by the emergence of an academic culture true to the principle of he who pays the piper calls the tune.

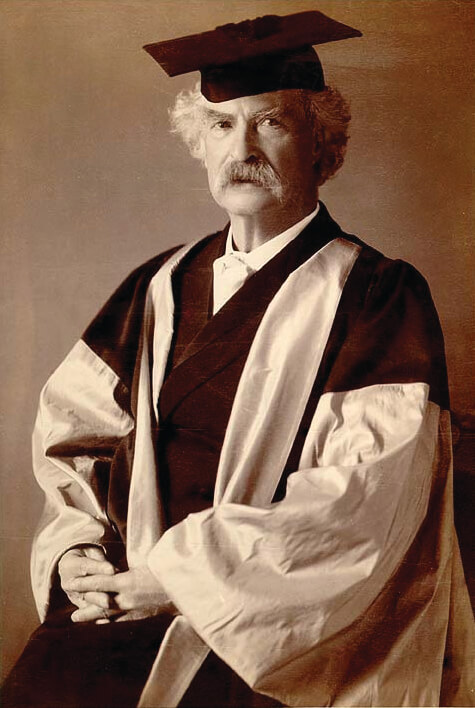

Future cardinal John Henry Newman argued in the 1850s that research was antithetical to the university’s role of promoting humanistic values. (Wikimedia Commons)

To determine where the moral and economic crisis in university research began, we might consider the case of Mark Twain. For some years I have been working on a book about his career as a critic of American imperialism. During a recent research trip to the University of California–Berkeley, I consulted the Twain papers in the Bancroft Library and made discoveries that have inspired me to think of him in a new way. I see him now as someone who represents cultural values that are in steep decline. Their virtual disappearance has contributed decisively to the transformation of the university’s research mission today.

I spent a week examining Twain’s notebooks, having perused his correspondence on an earlier trip to the archive. The notebooks, bound in leather and dated by year, contain jottings and extensive comments about what he was reading and researching at every stage of his adult life. They reveal the workings of a restless, intellectually curious, and probing mind. Reading them, one must wonder where this intellectual zest and prowess originated. Although his formal schooling ended when he was 12, as near as I can tell from the historical documents, Twain seems to have read his way to enlightenment. He read voraciously but in a disciplined way, always with a purpose in mind, usually concerning the book he was writing at the time.

Twain trained himself to become a skilled researcher. Working on his 1896 novel Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc, he wanted to learn about the economics of medieval warfare: who paid for the soldiers, how were they assembled into an army, and for what political purposes in historical reality as opposed to the stated purposes in the government propaganda of Joan’s time. His correspondence from this period is filled with requests for information about historical sources that would enable him to depict authoritatively the Hundred Years’ War in which Joan played an epic part. A source of great use to him was Jean, sire de Joinville’s Histoire de Saint Louis, a chronicle of the Seventh Crusade (1248–1254). This is a book I have my students read in our great-historians course at the University of Montana. It impressed me deeply to see how much Twain learned from Joinville’s firsthand account of the stupidity, greed, and cruelty of warfare during the Crusades, research findings that he then transformed into his last completed novel. It was the book of his that he loved the most.

I was also struck in reading the notebooks by Twain’s passion for foreign-language study. Living in Austria in the late 1890s, he made a sustained but not entirely successful effort to become fluent in German. He once claimed in the Twain manner of comedic hyperbole to have made 63 grammatical errors in one 47-word-long German sentence. But he relentlessly pursued the language with lessons and tutors, relishing every opportunity to speak German with his Austrian friends and neighbors. He saw to it that his children learned German and insisted that for two hours every day they speak only in that language. His notebooks are full of German words and phrases. When in 1892 he and his wife, Livy Langdon Clemens, had spent time in Rome, Florence, and Venice, his notations suddenly acquired an Italian flavor. Columns of Italian words and phrases fill up the notebook for that year. There were intrinsic benefits to learning foreign languages, Twain believed. He thought that Europe was the mother culture for Americans, and language study would help us keep in touch with it. Any activity that weaned Americans away from their inveterate provincialism would be worth encouraging.

Mark Twain, begowned to receive an honorary degree at Oxford, worried about the oligarchy’s influence in the Gilded Age. (Wikimedia Commons)

The notebooks document Twain’s transition from rollicking entertainer to anti-imperial moralist. Although Americans of his generation thought of Twain primarily as a comic writer, he believed that some subjects were not funny. He was living in Austria when the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898. Twain expressed revulsion at the outcome of this conflict, which he saw as the beginning of an American empire in Latin America and the Pacific. After that war, he began to identify American imperialism and militarism as existential threats to the country. American foreign policy in the 1898 war and in the Filipino-American War following it he thought larcenous in intent. He joined and took a leadership position in the Anti-Imperialist League, writing such antiwar essays as “To the Person Sitting in Darkness” and “A Defense of General Funston.” His reading, as the notebooks disclose, became more historical and strongly tended in the direction of social criticism.

The most interesting and important research discovery that I made was in Twain’s 1902 notebook. In the December 22 entry, he recorded meeting at a New York dinner party “Hobson of England.” This would have been John Atkinson Hobson, the author of Imperialism: A Study, which had appeared earlier that year. Hobson is rightly faulted today for his anti-Semitic views, but as a general proposition, he made profound points about the power of money over domestic politics and foreign policy. I am in no doubt about how Twain would have conducted himself at that dinner party. He would have peppered Hobson with questions about the prodigious research and brilliant reasoning that went into the book, the better to formulate the arguments he was making in his own anti-imperialist writings.

I am still formulating some of my historical judgments about Twain, but at this point I have a clear idea of him as a man. Despite many inconsistencies in his character, particularly regarding an obsession with money and stock speculation, I hold him in the highest esteem. He started out in life with nothing, no advantages of education, family, or money. He was a junior high school dropout who by all odds should have left this world without a trace of historical significance. Yet, he ranks as one of our greatest writers and one of the most perceptive and courageous witnesses of the age in which he lived.

It did not surprise me to find Twain’s pervading influence in Steve Fraser’s The Age of Acquiescence: The Life and Death of American Resistance to Organized Wealth and Power (2015). Fraser compares the political responses to the Gilded Age of the late 19th century with those to the Gilded Age of today, both eras of sharp income inequality and tight political control by financial elites. Indeed, the name for this period in American history comes from Twain’s 1873 novel, The Gilded Age, co-written with Charles Dudley Warner. In the 1860s, Twain had worked as the secretary for William Morris Stewart, a U.S. senator from Nevada. Twain called Washington politics the least complicated subject that had ever come to his attention. Essentially, the system worked as a form of legalized bribery. A chapter titled “How Appropriation Bills Are Carried” is a satirical examination of the turbid world of lobbying for land, water, and railroads. Beriah Sellers, the supreme conman, and the utterly corrupt Senator Abner Dilworthy are the paramount human symbols in American literature of the defects in our nation’s politics, past and present.

Fraser explains why the resistance to plutocratic power was much tougher and more biting for Twain’s generation than is the resistance of today’s Second Gilded Age. Our 19th-century forebears did not take their exploitation supinely, the way we do. Why, Fraser asks, has there been so little resistance to modern plutocracy? Minority rights and gender equality have scored some important successes, but they have not carried over into effective opposition to economic inequality and corporate domination. Based on ideas drawn most importantly from historian and social critic Christopher Lasch, Fraser theorizes that the absolute triumph of capitalism and consumer culture has undermined the American national character. When the United States began its rise as an industrial power in the 19th century, Americans still possessed an agrarian work ethic characterized by “frugality, saving, and delayed gratification, as well as disciplined, methodical labor.” These traditional values are at odds with the moral and psychic economy of the Second Gilded Age—a time when the country’s manufacturing base has been outsourced and the values of the family farm almost entirely erased from the collective memory. The first economy depended on the work that produced the necessities of life, the second on consumerism and finance, leading to a culture of debt, speculation, risk, and waste.

The corporate domination of American society decried by Fraser extends to the universities. Like the media, the institutions of higher learning are intertwined with the country’s power blocs. Although concerned primarily with the broad cultural consequences of the structural transformation of American society, Fraser does write in passing about student debt as a factor negating the critical energies that formerly quickened university life. Many other factors contribute to the problem of campus timidity and conformity today, but the real crisis of higher education stems from the assimilation of the university into the corporate order.

This deep penetration of universities by marketplace forces compels higher education administrators to seek market share through curricular maneuvers motivated by concerns about customer relations, rather than educating students in the humanistic values conducive to self-governing citizenship. The university world has transformed itself into an upwardly striving parody of the marketplace. While rhetorically invoking bygone academic standards and values, school leaders as a class, by their policies and decisions, reveal a serious commitment only to bottom-line realities.

The writer and critic of higher education William Deresiewicz [a contributing editor of this magazine] has addressed how the transformation of American culture during the Second Gilded Age has affected university life. Neoliberalism in a university setting, Deresiewicz explains in Excellent Sheep: The Miseducation of the American Elite and the Way to a Meaningful Life (2014), deceives students into thinking that they are valuable only for their activity in the marketplace, meaning their success in obtaining employment and getting ahead in a remunerative career. Consequently, undergraduate life consists, on its serious side, of résumé building as a means of meeting workforce needs. With college costs and student debt sharply rising, students no longer feel free to explore the life of the mind. They are compelled to make every tuition dollar and college credit count toward their own professional advancement. For all but an ever-shrinking minority of students, other academic considerations lag far behind. Thus, we are witnessing on college campuses a stampede into vocational fields and an abandonment of the humanities, indeed of the very idea of learning as a means of enriching the mind.

The crisis in higher education deeply conditions university research. Marcia Angell, the first female editor of the New England Journal of Medicine and a member of Harvard University’s Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, published in 2004 The Truth About the Drug Companies: How They Deceive Us and What to Do About It. Academic medical centers and teaching hospitals figured prominently in her analysis of the pharmaceutical industry’s tainted system of research and development. She describes a research culture corrupted by conflict-of-interest relationships involving university scientists with grant and commercial ties to the companies whose products they were testing. For the more than $200 billion then spent on prescription drugs every year, Americans were not getting, in many cases, honestly tested products from the drug companies and the universities that did research for them. Moreover, science itself has become increasingly commercialized by the economic blessings of a technology transfer policy excitedly encouraged by university administrators in thrall to the revenue stream gushing from marketable research for vested economic interests. Campus technology transfer offices have become hives abuzz with entrepreneurial gusto at all the better schools.

Two years later, Angell’s shocking follow-up article, “Your Dangerous Drugstore,” appeared in The New York Review of Books as a warning about the real costs to public health of prescription drugs. She calls into question the scientific integrity of clinical trials where the sponsoring drug companies themselves intervened in the research and conditioned it. Through the suasion of money or manifold professional inducements, they have succeeded in keeping a corrupt system in place. To fall out of the loop of corporate sponsorships could involve serious career consequences for uncooperative researchers. It is impossible to find in these hustling arrangements an unbiased and impartial role for the scientists. In a 2009 lecture on our campus, Angell raised some extremely troubling concerns about the dangers threatening the integrity of university research and the need for a truly independent review process. Concerns such as those she presented affect the university in its entirety, not only science faculties involved in research on prescription drugs.

The greatest distortions in the university’s research mission originate in the relationship between industry and the military. Sociologist C. Wright Mills noted in 1956 in The Power Elite that with scientific and technological development increasingly part of post–World War II American military preparedness the government became the country’s largest single financial supporter and director of science research. The militarization of science made the university increasingly dependent on the permanent war establishment. In its various defense-contractor capacities, higher education stood at risk, Mills feared, of functioning as an adjunct of the war machine. War, long known to be the health of the state, was proving to be the health of university science departments.

President Eisenhower made a similar argument in his farewell address on January 17, 1961, warning the American people about the dangers present in what he called the military-industrial complex. In particular, he worried about the detrimental impact of military spending in charting the direction of university research. Department of Defense contracts, he reasoned, would have a determining effect on what university scientists chose to research and how this work would be funded. Since 1961, federal expenditure on the military has continued to grow, along with the university’s direct and indirect role in weapons research projects. The Reagan administration accelerated military spending at record rates, and no president since has been able to curb the Pentagon’s voracious appetite for tax dollars. In retrospect, Eisenhower’s forebodings about the Pentagon’s effect on university research appear to have been understated.

The militarization of scientific research at leading universities intensified after 9/11. Henry A. Giroux observes in The University in Chains: Confronting the Military-Industrial-Academic Complex (2007) that Department of Homeland Security funding has added a whole new network of teaching and research initiatives on university campuses. Militarized knowledge and research are now fully compatible with university life. A 2002 report estimates that some 350 colleges and universities conduct Pentagon-funded research. Department of Defense funding now includes grants for research in the fields of electrical engineering, computer science, metallurgy and materials engineering, and oceanography. Intelligence agencies recruit social scientists and use their research for counterinsurgency purposes. Giroux sounds an alarm about the transformation of a university world riddled with secret military and intelligence projects for the advancement of the corporate globalist order. The book ends with a lament for the annexation of university research by defense, corporate, and national security interests.

In 2014, Giroux updated his concerns about the military-industrial-academic complex in Neoliberalism’s War on Higher Education. In the seven years between the two books, the national security state had become even more entrenched in American universities. As adjuncts of corporate power, the schools had steadily lost their primary character as liberal arts institutions. Classrooms had become increasingly open to the Department of Defense and the national intelligence agencies, a process epitomized for Giroux at Yale University. In that illustrious academic setting, the Department of Defense was slated to fund a program—the U.S. Special Operations Command Center of Excellence for Operational Neuroscience—to teach new intelligence-gathering techniques, with New Haven’s immigrant population as test subjects. Community outrage scuttled the plan. Even the Ivy League might not be immune to the intellectually disfiguring effects of a militarized academic environment.

Seymour Melman, the late professor of industrial engineering and operations research at Columbia University’s Fu Foundation School of Engineering and Applied Science, argued in The Permanent War Economy: American Capitalism in Decline (1974) that the country was in systemic economic crisis. Through the mystifications and malversations of high finance, the economy would continue to do well for economic elites, but ordinary people could forget about living the American Dream. He judged the American economic and industrial system to be in a condition of imminent doom because of the depredations of a 30-year military economy created under government control for the benefit of corporate interests.

Based on the production of goods and services that are not economically useful for living, he wrote, the permanent military economy had become a parasite that in its growth had proceeded to devour the vital organs of its host. A byword for corruption and cost overruns, the wasteful military economy originating in the Second World War had grown to dominate the whole American economy while infecting and undermining its productive capabilities. Big military budgets and ever-increasing defense spending by a Congress obedient to the lobbyists of giant defense contractors were starving other government-investment fields, such as health care, housing, education, and infrastructure. Research and technical manpower had been drawn off from civilian industry into work supporting the military economy. The country’s ever-growing trade imbalances revealed how uncompetitive and inefficient the American system had become. The acceleration of the globalized economy would aggravate all the negative trends identified by Melman in his book 45 years ago.

About education, Melman had relatively little to say, but he predicted that as a segment of the enterprises and research organizations serving the country’s defense needs, universities would be enmeshed in the disastrous consequences of a permanent war economy. The main business of the Pentagon concerned the defense and augmentation of a world Pax Americana for corporate interests. Like all past empires, the current American model would find helpers, rationalizers, and enablers to meet its needs. Research dollars would be the prime method of getting universities to ignore the larger issues of imperialist domination and control.

A campaign for the salvation of American universities might begin with a fresh look at Thorstein Veblen’s 1918 The Higher Learning in America: A Memorandum on the Conduct of Universities by Business Men, which he began to write in 1906. Even then, Veblen worried that the university could not remain loyal to its fundamental calling of conserving and extending the domain of disinterested knowledge. Fearing the corrupting influence of utilitarian and commercial pedagogical approaches on scholars and scientists, he predicted that true university teaching and research would fade as higher learning yielded to the demands of pecuniary power elites. Though favoring American intervention, he subsequently argued that the Great War, through rampant chauvinism and invidious patriotism, created the danger of yet another check on the pursuit of learning. The full development of the military-industrial complex and its heavy presence on campuses lay in the future, but Veblen soon understood that the captains of war would be joining the business elites in adapting the university to nonacademic ends. He foresaw a dark future for science and scholarship at schools hawking commercially feasible instruction and, as an added infirmity, making sports the centerpiece of university life.

Veblen argued that everything in the American university should be made subordinate to the pursuit of academic excellence. Because the single-minded quest for knowledge and the transmission of it constituted the only authentic purposes of the university, the role of research would have to be paramount. Indeed, the research work of professors was indispensable to their classroom success. A great admirer of the 19th-century German research university, Veblen stood squarely with Ranke on this matter. Research time for professors had to be protected and not dissipated with various forms of fluff. The academic culture of proliferating committee assignments deeply offended him as something much worse than a distraction: it was becoming a replacement for real university work. Above all, university research had to be undertaken in a critical spirit, not in an echo chamber of support for ruling class opinions and interests.

The ideals that Veblen set forth remain worthy of contemplation. What he said, particularly about the limitations on university research, is even more apt today than it was early in the 20th century. The best writing on higher learning in America continues to draw from the ideas and values in his bitter but never hopeless jeremiad. He could not have written it without hoping that university scholars of the best type would continue to arise and keep the worst from happening.

As a practical matter, the integrity of university research can be restored only by fulfilling the promise of American democratic civilization. In the lengthy introduction to Henry Adams’s posthumously published The Degradation of Democratic Dogma (1919), his brother Brooks lamented how the cause of democracy had been subverted in America by oligarchy. President John Quincy Adams, the grandfather of the Adams brothers, had tried to advance the common welfare by means of an “American System,” a plan for collective development. He advocated a role for the federal government in supporting education and science to aid the advancement of republican virtue in American society. The fundamental question then facing the country, President Adams reasoned, concerned the choice between an education of conservation and an education of waste. The country proceeded to make the wrong choice and gave free rein to the speculators. Instead of a cooperative national agenda of internal improvements, with education leading the way, the common welfare became subordinated to private profit.

The way was made straight for Beriah Sellers, Senator Abner Dilworthy, and their flesh-and-blood heirs down to today. Twain did not need the superb education and extensive political experience of John Quincy Adams to understand the prevalence of oligarchic realities over American democratic ideals. To write his obituary for American democracy, The Gilded Age, Twain only had to keep his eyes open to see how matters stood in Washington. Everything in the country—the land, timber, water, railroad rights of way—was for sale to the highest or most connected bidder, with no concern for a higher civilization than the market kingpins and their lobbyists would allow. Inevitably, university education and research would come under the same market imperatives. The American university stands before us today as a leading example of the degradation of democratic dogma, and only genuine democracy can save the universities and the country from the fatal ravages of oligarchy. Neither of the Adams brothers gave the American people a fighting chance to save democracy from the forces degrading it. We have little choice but to prove them wrong.