Union: The Struggle to Forge the Story of United States Nationhood by Colin Woodard; Viking, 432 pp., $30

The anthropologist Sally Falk Moore thought that some portion of legal reasoning was really masquerade. Studying colonial East Africa, she found that legal changes billed as rational reforms were, when viewed over a century, simply mirroring economic and political changes.

The implication? Seemingly disinterested law is a cover for politics. Judges and lawyers may not realize it, Moore wrote, but their careful arguments of legal norms really function as a means of displacing responsibility. Those involved are not reasoning; they are unwittingly disguising the exercise of power behind a vague abstraction called The Law.

I kept thinking of Moore’s argument while reading Colin Woodard’s Union: The Struggle to Forge the Story of United States Nationhood, an exploration of the ideas that guided the country from its first days as a fragmented alliance against England—what Woodard calls a “contractual agreement”—to a monolithic Great Power after World War I.

In Woodard’s version of this story, it is not judges and lawyers who mistakenly think they are engaged in a rational inquiry when they aren’t, but intellectuals. Woodard’s subjects sincerely believe that their work is original, that they are thinking independently. But he makes us see that their most cherished accomplishments are but flecks of foam on the tide of history moving through them.

Woodard, whose previous book American Nations (2011) plumbed the regional divisions of early America, has chosen as his subject five influential American writers and leaders of the 19th century, beginning with statesman and historian George Bancroft, Confederate novelist William Gilmore Simms, and abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Historian Frederick Jackson Turner joins the action later, along with his lifelong friend Woodrow Wilson, for whom Woodard reserves some of his most scathing passages. Union culminates with an exegesis of the 28th president’s resolute racism, as well as his distasteful habits. (He routinely used a siphon to empty the contents of his stomach.)

Through the stories of these men, Woodard traces a gradual, emerging consensus of American unity. It’s a dark tale. This country purchased its sense of itself as a unified whole at a high price, he writes: that of racial equality. He shows how Bancroft’s vision of the nation’s triumphant destiny and Simms’s fanatical white supremacy fused and made possible Wilson’s reconciliation of the white North with the white South at the expense of everyone else, especially the descendants of its former slaves, whose aspirations Wilson decisively crushed. As a writer of history, Wilson was vague, stilted, and conciliatory, cheerfully insisting on the “mischief of Reconstruction” as he whipped the work of other writers into a smooth concoction of American and Aryan superiority. As a politician, he was ruthless, callously betraying the civil rights advocates who supported him and segregating the federal workforce, which had been peacefully integrated for 50 years.

Woodard starts with Bancroft, whose long life makes a ready vehicle for exploring high-minded American preoccupations in the 19th century. The son of a Unitarian minister, Bancroft attended Harvard and spent his formative years in Germany when it was a fragile multiethnic alliance of formerly independent kingdoms, principalities, duchies, and free cities, like the weak association that was the early United States. Woodard

re-creates in magical detail the hike Bancroft took across the European continent in the early 1820s. He covered hundreds of miles and met, it seems, every luminary of the era: Alexander Humboldt, the Marquis de Lafayette, Washington Irving, Lord Byron.

Yet the priggish young man returned home with his astonishingly provincial worldview intact. He would live his entire life smug in his conviction that faith and reason were compatible, that enlightened rationalism and Puritan hopes of a godly society had produced a chosen nation. The vast history Bancroft would eventually pen was rife with wishful thinking. But a fragmented young country seized on his argument that America was destined by Providence to carry the torch of human freedom handed off from Europe, and all who followed Bancroft had to contend with this script, even as his Yankee contemporaries deplored his politics. (Although antislavery, Bancroft ultimately served Democrats who sought to secure the future of slaveholding in Texas.)

Simms, a contemporary and fervent advocate of Anglo-Saxon racial superiority, grafted Bancroft’s prophetic sensibility onto his views that slavery was the natural order and sectional loyalty was paramount. Douglass, the escaped slave, took Bancroft’s script in a different direction, turning the torch of American freedom back on itself and illuminating the nation’s hypocrisies. By the time Turner and Wilson have their turn at the unifying theme, we are growing used to the way American thinkers keep rehashing the same mishmash of Calvinism, the German Enlightenment, expansionist ambition, Romantic nationalism, and whatnot in an effort to make America cohere.

When Wilson’s vision of Anglo-Saxon ethno-nationalism finally prevails—subtly recasting Abraham Lincoln as a hero of reconciliation rather than of abolition, and segregation as renewal—we understand how provisional that victory is and how unrelated to actual intellectual insight. Wilson’s triumph is a purely political one; his ideals merely disguise unity on southern terms under an abstraction called “progress.” Even so, invisible tides keep surging: already, by the close of Union, the first mass African-American civil rights demonstrations are being organized in response to Birth of a Nation (1915), a film Wilson endorsed.

Much of this is familiar history. But in Woodard’s hands, it leaps to life. He shows just how powerful a form popular nonfiction can be in the hands of a disciplined writer who won’t tolerate generality or abstraction. Union moves quickly, skipping from one anecdote to the next. The lens is narrow. Physical detail is prominent. The writing is relentlessly accessible. We learn a great deal about his subjects’ petty concerns and shortcomings and of the long stretches between accomplishments when they merely muddled along. We learn of unhappy marriages, children who die, problems with procrastination and fame. And all of it matters. Beginning with the simplicity of fable, Union quickly builds into a surprisingly complex work of intellectual history. Woodard’s earthy description of Simms’s first journey into the Mississippi backcountry in 1824 reveals more about the fragmented character of early America than any political science treatise could. The journey through war-torn swamps and dense woods takes weeks, the track so rough that Simms’s fellow passengers have to pile to one side of the coach to keep it from flipping over.

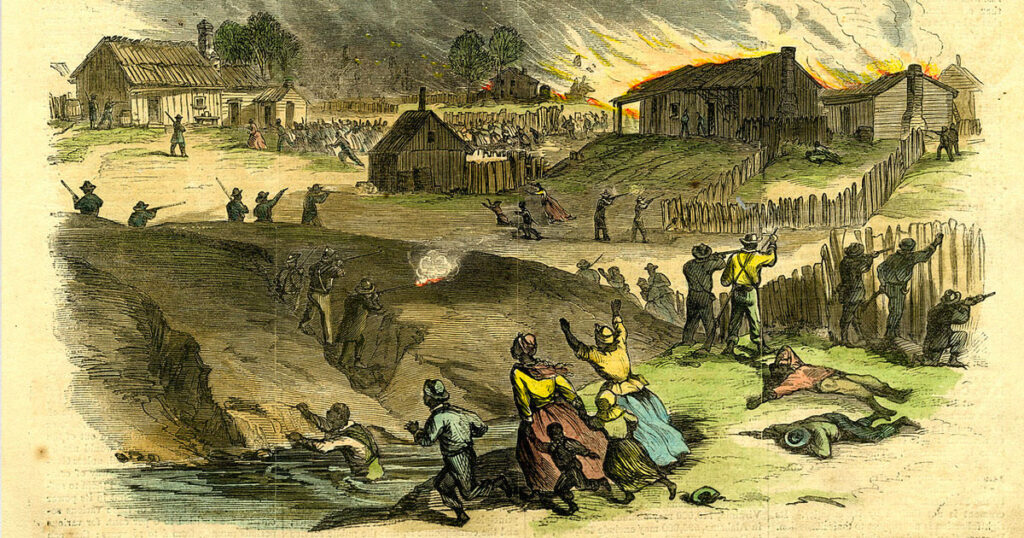

Two-thirds of the way through Union, I realized that the slowly accumulating detail was giving me a tight throat. Just about any history of the Civil War and its aftermath—of Lincoln’s assassination, of the failure of Reconstruction—makes for painful reading. But Woodard’s spare style makes this history especially depressing. “Regulator gangs murdered five blacks in as many days in the summer of 1865: one for being a preacher, two more for having witnessed the killing, another for having attended a dance, and a child whose hands and ears were cut off and throat slit for pleasure,” he writes of Reconstruction-era Mississippi. Woodard is businesslike in his narration and doesn’t linger on such episodes. But it’s enough: we know where this is headed.

And so Woodard’s subjects lurch from youth to old age. Bancroft, blinkered as ever, fades into fusty irrelevance; his works would be mostly forgotten. A despairing Douglass takes a last chance on marriage. Turner, ravaged by grief over the loss of two children, quietly doubts the frontier thesis that made him famous and perennially disappoints his publisher. This is that rare history that tells what influential thinkers failed to think, what famous writers left unwritten. Douglass emerges as the most consistent figure of the century, the one whose convictions were the steadiest and most authentically won. Yet even he appears tossed by tides he can’t fathom.

For anyone who places a high value on thought, this book gives pause. Not just the familiar story of intellectuals drafted as mouthpieces, it shows how even the most exceptional minds serve prevailing currents. Woodard demonstrates that something more complicated than reason is always afoot, some swirl of politics, events, and wordless popular sentiment that sweeps the hapless thinker in its wake.