A few years ago, during a shamanic ceremony in Colombia, I ingested ayahuasca, made of Banisteriopsis caapi, a South American vine employed for hallucinogenic purposes. Ayahuasca is a “plant teacher.” It pushes the mind into unforeseen realms. No wonder indigenous tribes in the Amazon make it an essential companion for religious quests.

Using words to describe what I went through defeats the experience. I wrestled with this challenge in my book The Oven: An Anti-Lecture (2018), which also became a one-man theater show staged across the United States. The extraordinary out-of-body education the drug afforded me left a deep mark. I felt unconfined, physically as well as spiritually—and at one point, I miraculously underwent a mutation that turned me into a jaguar roaming for prey in a vast landscape.

Once I got home, I immediately reread the Popol Vuh (1554–58), the sacred origin book of the Maya. I became fascinated by the multiple adventures of Hunahpu and Ixb’alanke, twins who at one point traverse the underworld, known as Xibalba—a habitat as intricate as Dante’s hell—where they face, among dozens of other creatures, bat monsters called camazotz. In the narrative, these creatures have the terrifying strength of the Cyclops in Homer’s The Odyssey.

I soon realized that in the shamanic ceremony, I had also visualized myself into an assortment of other creatures, a few of them impossible to describe: part human, part deity, with a few recognizable features but many more I had never encountered before. I delved into pre-Columbian sources in search of them—encyclopedias, testimonies of the Spanish conquest, historical chronicles of life in colonial times under European rule. What I found astonished me: the sources I looked at were themselves inconsistent and described these beasts in fanciful fashion.

It took me time to understand that this ethereal quality is precisely what makes these creatures distinct. I felt the inescapable urge to retell Popol Vuh for a contemporary readership; I also got the inspiration that led me to compile an anthology of pre-Hispanic imaginary beings, quoting from both real and fabricated sources.

In the land of Magical Realism, what better way to pay tribute to these creatures than to celebrate their insubstantial status? Julio Cortázar, in his 1967 book, Around the Day in Eighty Worlds, writes: “I have always known that the big surprises await us where we have learned to be surprised by nothing, that is, where we are not shocked by ruptures in the order.”

I grew up in Mexico, so I know how elusive is the line between fact and fiction. Latin America is where what is known and what is hoped for intermingle. Needless to say, fantastic animals have always been companions to human civilization. The Bible is full of them, not only unicorns and cockatrices (in the King James Version, 1611), angels and cherubim, but also Behemoth and Leviathan, and, obviously, the Almighty, an omniscient being with anthropomorphic qualities whose only limitation appears to be—surprisingly—not to have been able to clone itself.

The Greeks had sirens, centaurs, satyrs, chimeras, basilisks, phoenixes, Pegasus, Medusa, Cerberus, and other entities. The Middle Ages were a fertile era for the creation of these creatures too: golems, dragons, and griffins, among others, would all be considered cryptids today.

Modernity added its own contributions, such as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1823), Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), and the massive black earthworm known as Mihocão. The production of fantastic creatures has only intensified over the past century, especially in the English-speaking world, with J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1937), C. S. Lewis’s The Chronicles of Narnia (1950–56), and, more recently, J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter saga (1997–2007).

Of course, what is fantastic to one culture is mundane to another. I ask myself, What did the indigenous people of Hispaniola, the first Caribbean island on which Columbus set foot, think of the Italian explorer and his companions? They probably believed the visitors were ether demons or gods. As the Talmud (Tractate Berakhot) argues, we don’t see the world as it is; instead, we see it as we are.

The Americas have long been a popular location to find monstrosities. Scientists like Charles Darwin and Alexander von Humboldt and writers like André Breton, D. H. Lawrence, and Allen Ginsberg all presented these continents as puzzling, deceptive places. This isn’t surprising; even today, the so-called New World remains a testing ground in which Europe envisions all sorts of enigmatic occurrences.

Jorge Luis Borges, along with Margarita Guerrero, edited the 1959 anthology Manual de zoología fantástica (Manual of Fantastic Zoology), expanded in 1967 and again in 1969 under a different title: The Book of Imaginary Beings. It includes creatures like the pygmies mentioned by Aristotle and Pliny; the chimera, a beast with the head of a goat sprouting from its back, a lion’s head at its front, and a snake’s head on its tail; and Emanuel Swedenborg’s angels, “the perfect souls of the blessed and wise, living in a Heaven of ideal things.”

Perhaps most vividly, in Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, published in 1967, a series of bizarre creatures visit the town of Macondo, including the gypsy Melquíades, who dies dozens of times yet is always youthful, and the naïve and angelic Remedios la Bella, whose out-of-this-world beauty ultimately makes her fly into the sky—neither of which is portrayed as monstrous.

In truth, my interest in pre-Columbian creatures dates back further than my ayahuasca experience, to the late 20th century, when I first read Moacyr Scliar’s The Carnival of the Animals (1968), which is full of the most whimsical American fauna. In my personal library, I have an array of volumes that attempt to portray them, a few of them lavishly illustrated. I have acquired artesanías that are the equivalent of action figures.

The six selections described below are all American creatures, both existent and invented by me, grounded in oral tradition but also traced in texts, real and imagined as well as the quotes, dating back to the 16th century, although some came to be—and were certainly recorded in historical documents—after the Conquest and during the colonial period that stretched until 1810.

In my childhood and in travels during my adult years, I have personally seen a handful of these creatures with my own eyes. During a night of conversation, I described them in detail to the legendary Mexican artist Eko. His superb depictions, included here, are approximations based on indigenous codices.

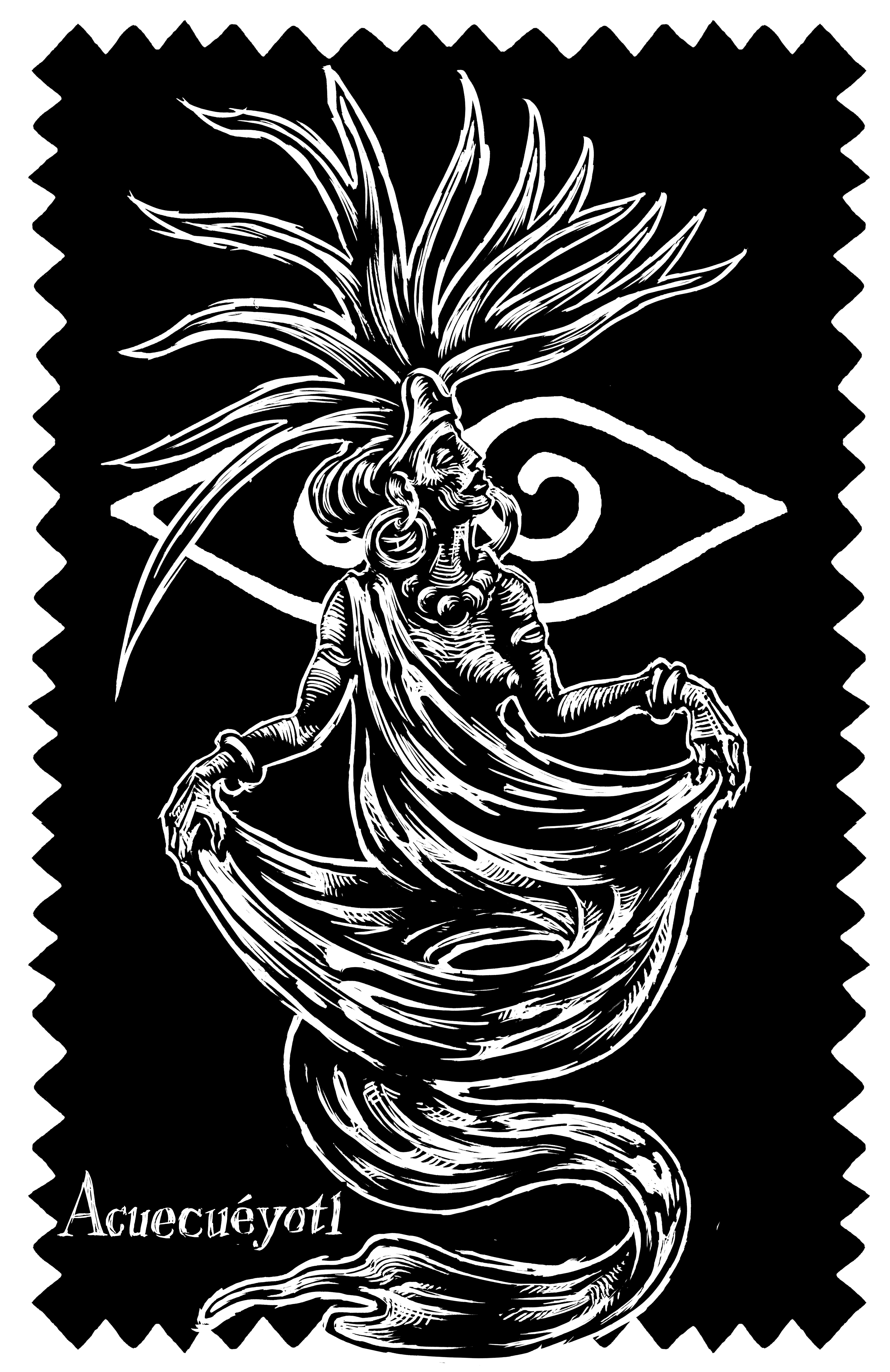

Acuecuéyotl

(ah-kueh-kueh-yoh-tl, Nahua)

The literal meaning of Acuecuéyotl is “wave of water” or “skirt of water.” The name refers to the sister to Tláloc, the god of celestial water. She also goes by the name of Chalchiuhtlicue.

She is similar to a nymph, and like the siren of Greek mythology, she lures sailors with her singing voice and enchanting music.

Acuecuéyotl is a wraithlike being who wears large round earrings, a pearl necklace, and a modest golden crown. Her beauty is delicate. Her physical appearance changes depending on the hour of the day. In lieu of hair, she has a sprawling maguey that leaks a seductive liquid.

For the Nahuatl, water was considered the earth’s nectar. Acuecuéyotl reigns harmoniously over rivers, lagoons, and the endless oceans. All those navigating on water are said to pay tribute to her. She is supported in her endeavor to fertilize the soil by the tlaloque, water creatures that, according to Ángel María Garibay’s 1985 book, Teogonia e historia de los mexicanos: Tres opusculos del siglo XVI (Theogony and History of the Mexican People: Three Small Works of the 16th century, 1985), are tasked with accumulating water in immense containers. The thunder that people hear in the middle of a rainstorm is the sound the tlaloque make as they smash the containers with enormous sticks, allowing the water to spill without aim.

Dominican friar Raúl Diego Santánder, in his book Libro de estrellas (Book of Stars, 1573–75), describes Acuecuéyotl as “a lover in a state of ecstasy.” He adds, “To be overwhelmed by it is to understand life’s true meaning.”

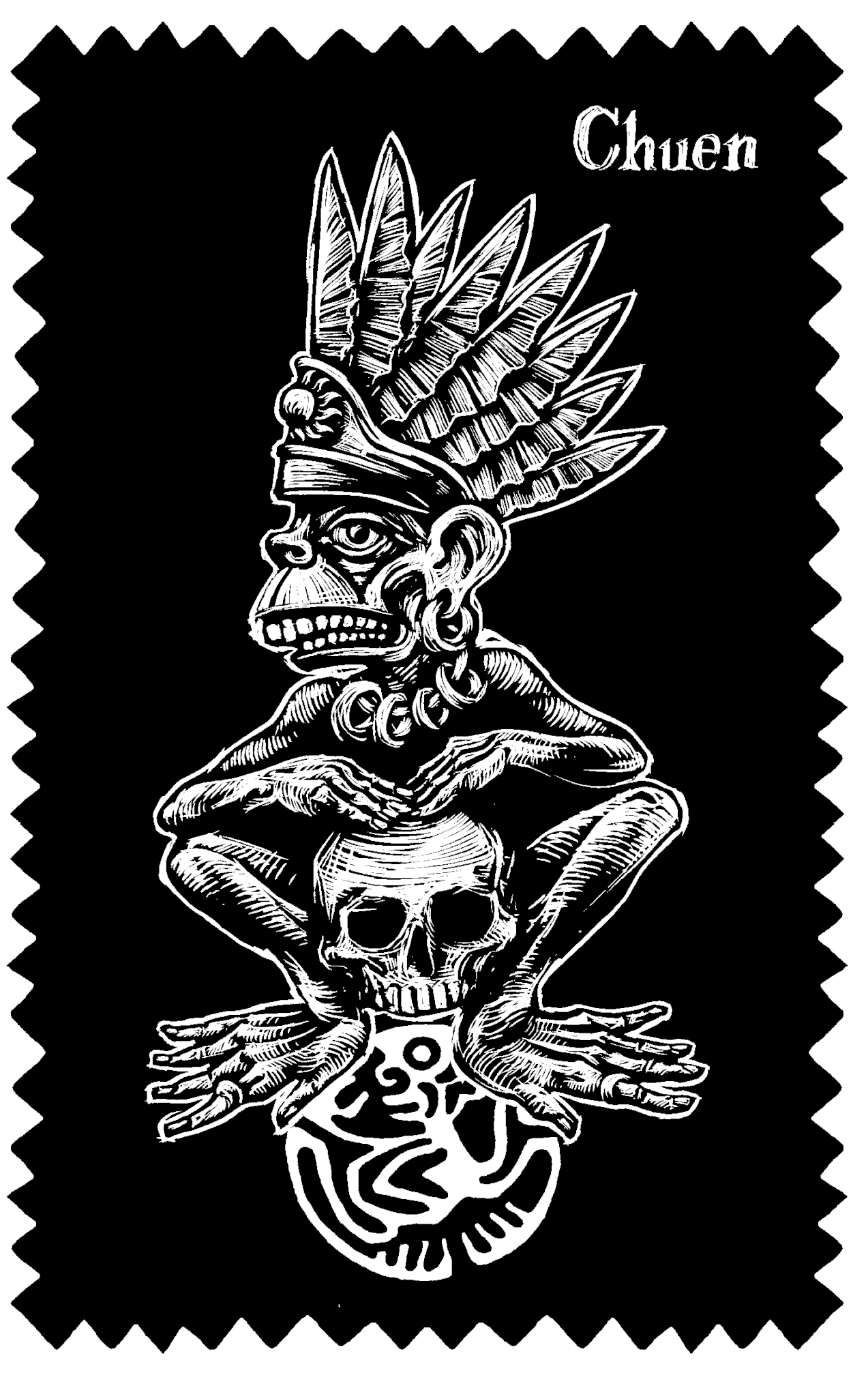

Chuen

(tchooen, Maya)

The Chuen is a symbol of irritation as well as harmony, opposites that attract each other. This creature is a monkey wearing a crown made of plantain leaves. In the front, the crown has an eye made of emerald, jade, and amethyst. The Chuen has human teeth and four human arms (two instead of legs), and it always wears onyx rings. It is accompanied by a skull, which the Chuen uses as a bongo to instigate anger. The monkey is rapidly annoyed by acts of human futility.

The Chuen is also a symbol of harmony. It knows the past, present, and future and is able to travel freely between them. Munro Edmonson’s Heaven Born Merida and Its Destiny (1986) described it as having been created with the vanished city of K’aak Chi (Mouth of Fire) in the Yucatán, in the crown’s eye, making it the city’s indispensable companion. (K’aak Chi was discovered by 15-year-old William Gadoury, from Quebec, Canada, through Google Earth images.) In a section called “The Birth of Uinal,” Edmonson describes the Chuen as prophetically counting steps back and forth in order to measure the landscape on which “a future city will be built one day.”

Occasionally, the Chuen has been confused with the carbuncle, a small creature spotted by Spanish conquistadores that, according to Borges and Guerrero’s Book of Imaginary Beings, supposedly “has some sort of shining mirror or jewel on its forehead, reminiscent of the gemstone by that name. Many explorers supposedly searched for it, hoping to secure a precious stone—but without success.”

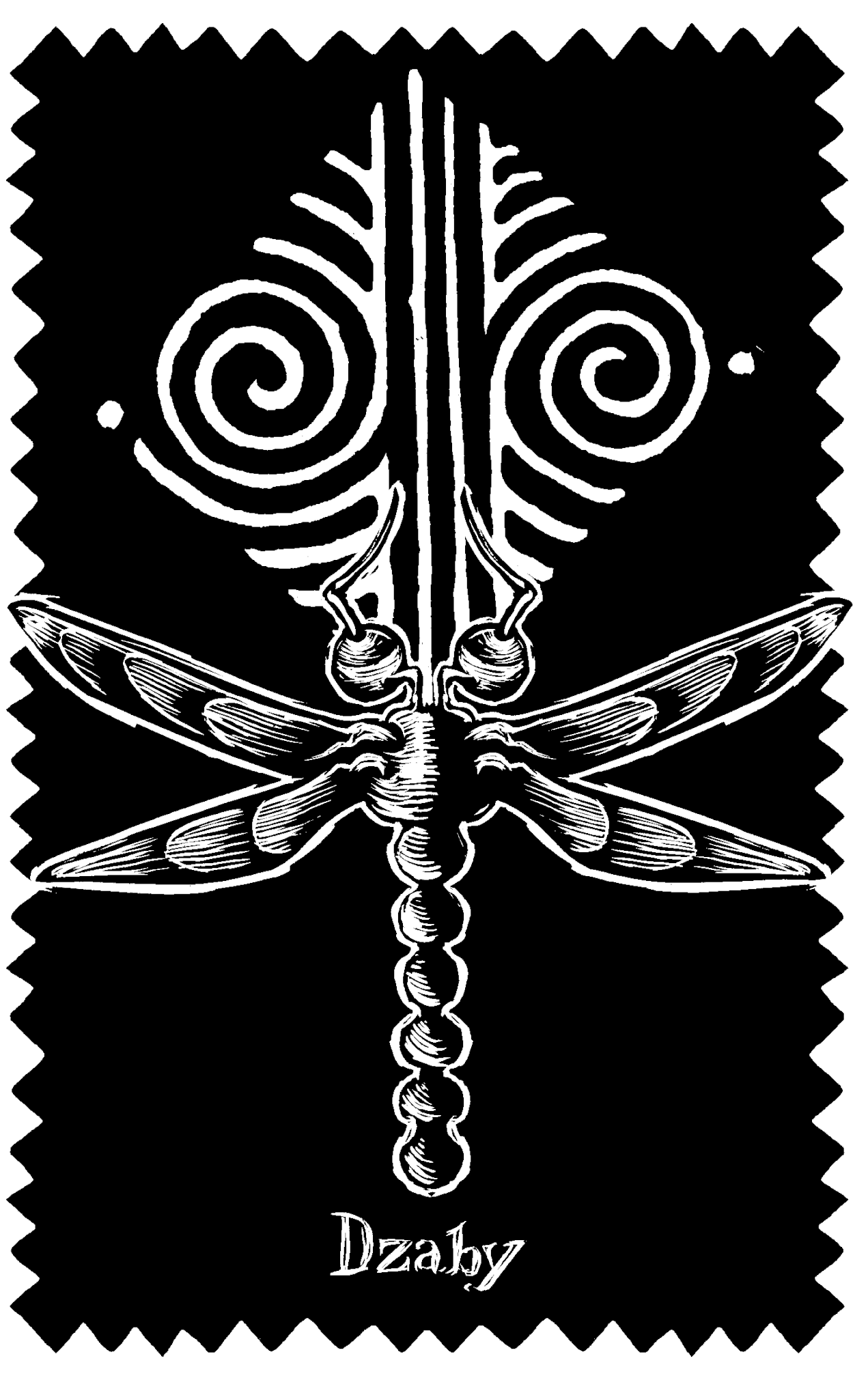

Dzaby

(dja-bee, Maya)

Known in English as a dragonfly, this insect belonging to the infraorder of Anisoptera is characterized by an elongated body, strong, transparent wings, and large, multifaceted eyes.

The dzaby is a uniquely logocentric insect. It feeds on a diet of letters. Different species prefer particular selections: in the Peruvian Altiplano, dzabys feed on Bs, Hs, Ts, and Zs; in the Mexican state of Quintana Roo, they prefer to Ns, Xs, and Ys; and in Hidalgo, dzabys pullulate toward three vowels: As, Es, and Os.

However, a Maya legend suggests that the first dzaby wasn’t attracted to the alphabet. Instead, it thrived in labyrinths, building nests in various locations inside them, then training itself to recognize various routes in and out of the maze.

Spanish romantic novelist and playwright Enrique Jardiel Poncela, author of the 1928 novel Amor se escribe sin hache (Love Is Spelled Without H), imported a dzaby colony from Cozumel to Madrid. He wrote a famous 1942 essay, “Una letra protestada y dos letras a la vista” (One protested letter and two letters on sight), in which he shrewdly called dzabys “the only creatures in the animal kingdom whose life is alphabetized.”

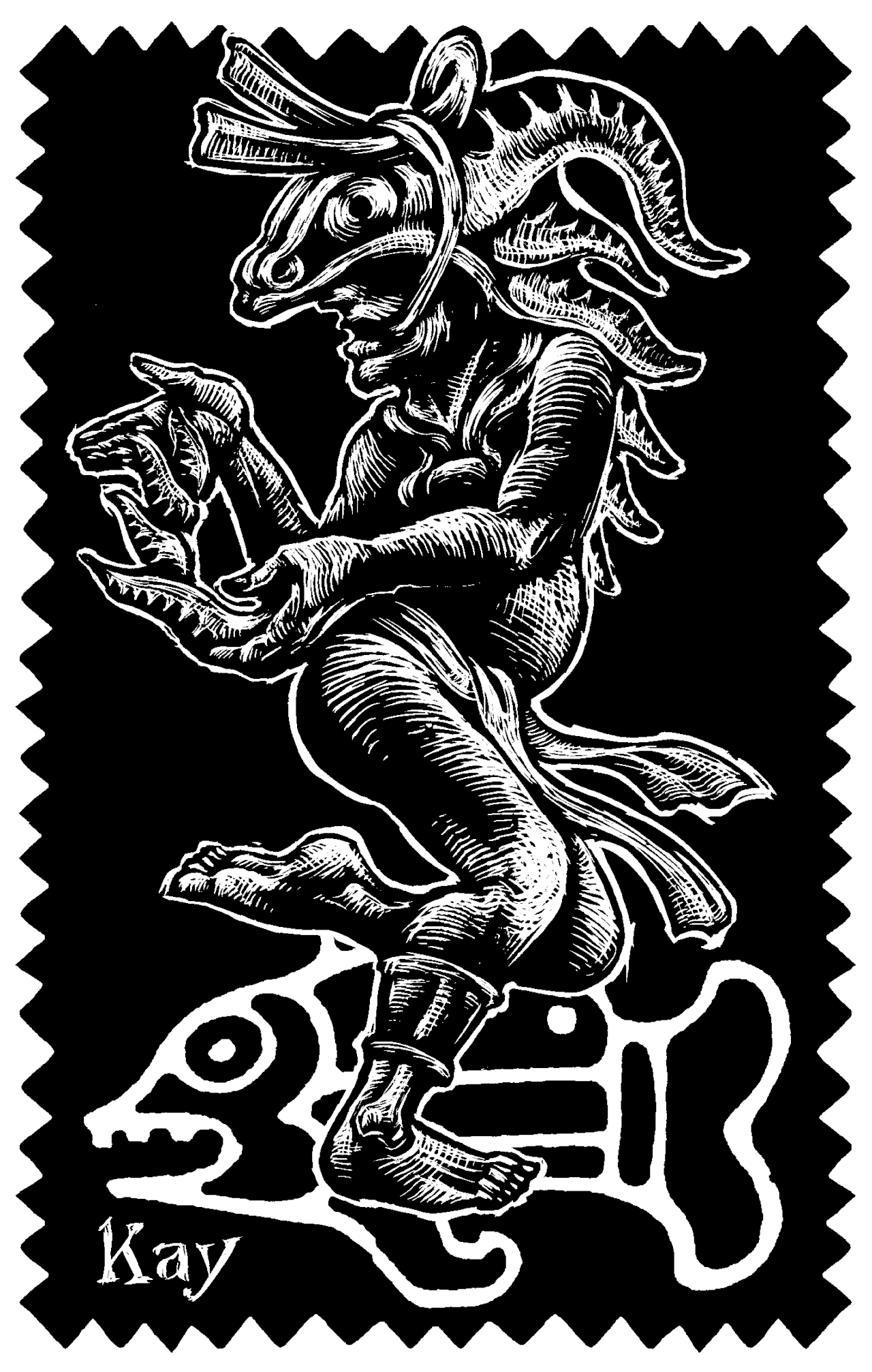

Kay

(kai, Maya)

Kay is an androgynous dancer with fish for hands. S/he also has several fish tied to his/her head. It is thought that Kay copulates with him/herself. With repeated oscillations, the dancer is known to become a pirinola, a spinning top.

Inexplicably, at various points Kay has been linked with Lewis Carroll’s Jabberwocky in Through the Looking Glass, and What Alice Found There (1871). Sandra Raziel Palante, a Maya poet from Quintana Roo, constructs his 2019 volume, El jinete con juanete (The Horseman With Bunion) around the killing of a beast called Kaybberwock.

He uses as his urtext the Spanish version of Jabberwocky, Diario de Poesía (1997) by Mirta Rosenberg and Daniel Samoilovich. To show the link, I quote the second and third stanzas—from Rigoberto Espaillat’s Jabberwock in Latin America (2002)—first in Carroll’s original, then in Palante’s tribute:

“Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch!”

He took his vorpal sword in hand;

Long time the manxome foe he sought—

So rested he by the Tumtum tree

And stood awhile in thought.“¡Con el Kaybberwock, hijo mío, ten cuidado!

¡Sus sexos que destrozan, sus mañas que apresan!

¡Cuidado con el pez Jubjub, hazte a un lado

si vienen las frumiantes Romburgezas!”

Empuñó decidido su espada vergoral,

buscó largo tiempo al monxio enemigo—

Bajo el árbol Tamtam paró a descansar

y allí permanecía pensativo.

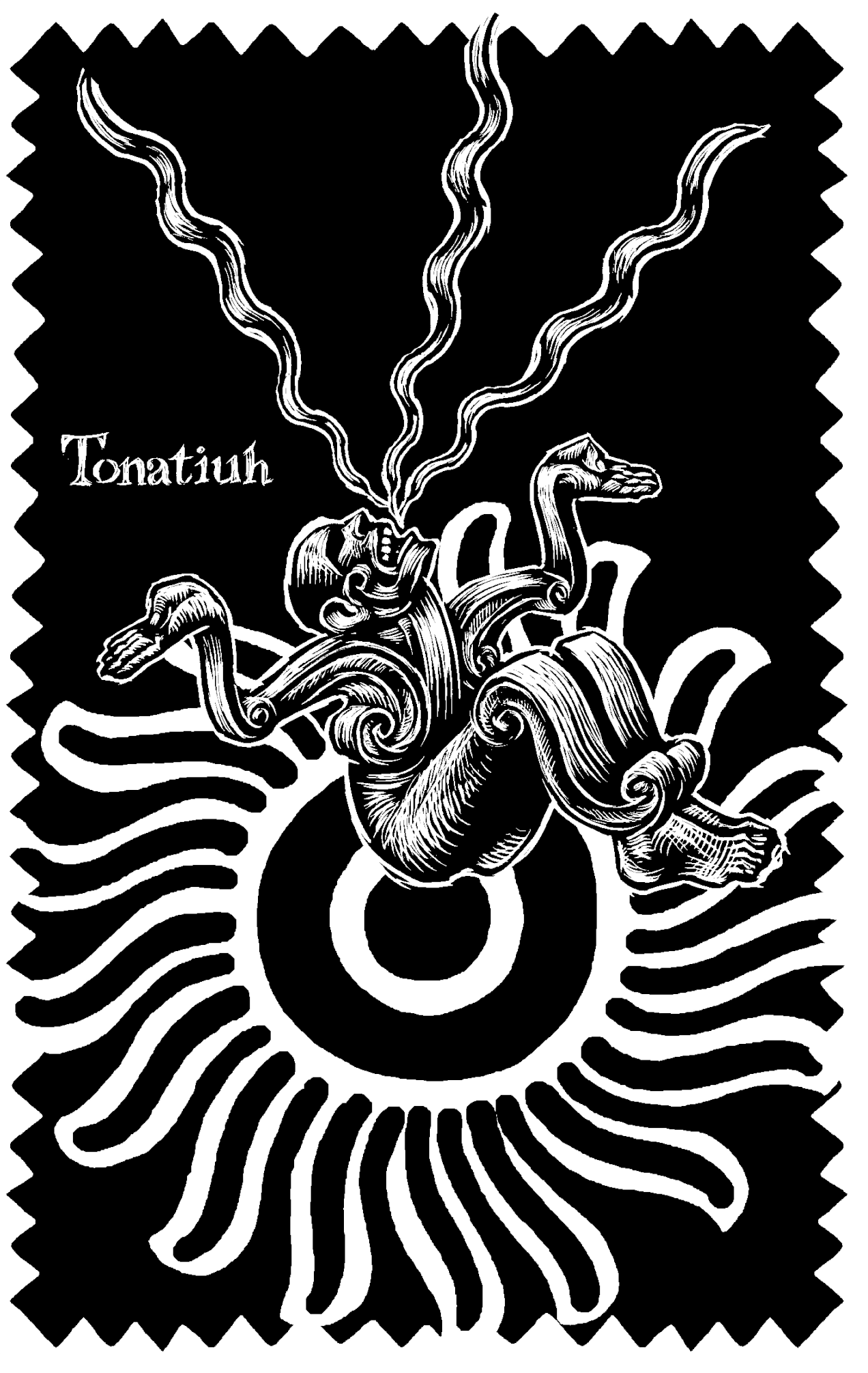

Tonatiuh

(toh-nah-tyoo, Nahua)

Tonatiuh is the fifth god of the sun. (The first four are Tiger, Wind, Water, and Rain.) He is also the patron saint of warriors. And in some accounts, he is the sun’s son. His face is believed to be at the center of the Aztec Calendar Stone. His defining color is red. He wears feathers. Eagles surround him.

Bernal Díaz del Castillo, in The True History of the Conquest of New Spain, finished in 1568, suggests that the Aztecs mistakenly believed red-haired conquistador Pedro del Alvarado, widely known for his aggressive character, was an incarnation of Tonatiuh himself. In a particular scene, Díaz del Castillo tells of an encounter between the Aztec emperor Moctezuma and Hernán Cortés and Alvarado. The following sequence precedes that scene:

The ambassadors with whom they were travelling gave an account of their doings to Montezuma [Moctezuma], and he asks them what sort of faces and general appearance these two Teules had [Cortés and Alvarado] who were coming to Mexico, and whether they were Captains, and it seems that they replied that Pedro de Alvarado was of very perfect standing both in face and person, that he looked like the Sun, and that he was a Captain, and in addition to this they brought with them a picture of him with his face very naturally portrayed and from that time forth they gave him the name of “Tonatio” [Tonatiuh], which means the Sun, or the Child of the Sun, and so they called him ever after.

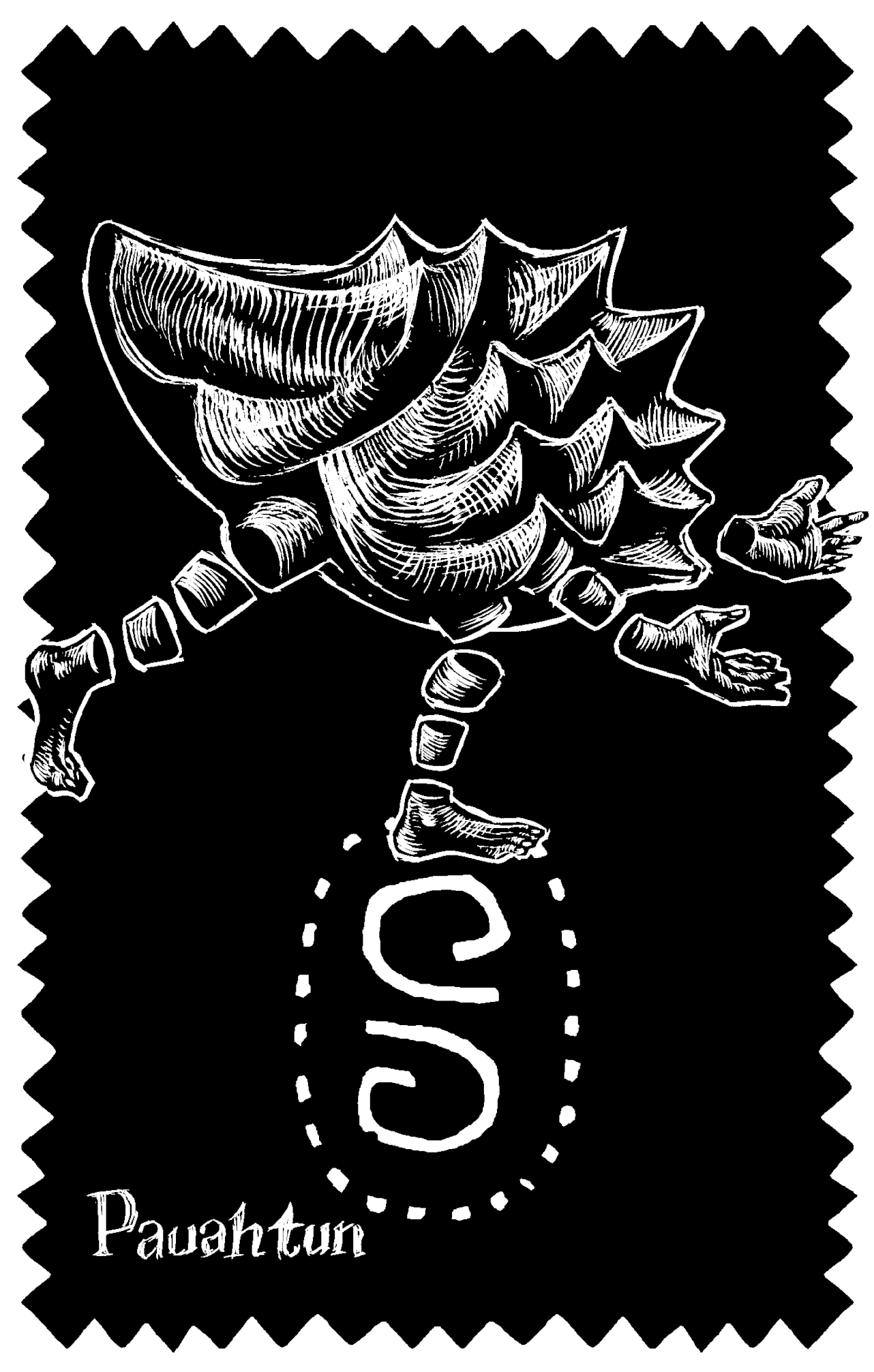

Pauahtun

(pah-gwah-toon, Maya)

This is a turtle shell or sea shell. The pauahtun is said to hold heaven with its strength. This creature is similar to an ocelot in that it has become a symbol for Mariana del Carmen Carvajal (1577–1611), a niece of Luis de Carvajal the Younger, who was burned at the stake by the Spanish Inquisition in an auto-da-fé in the Plaza del Quemadero in Mexico City. Like her uncle, Mariana del Carmen was a secret Jew. In a letter dated September 11, 1604, she described herself as having the pauahtun, a shell so conspicuous it allowed her to hide in plain sight. Identified with the biblical matriarch Leah, she held steadfast to her Hebraic beliefs until the end, evading persecution. Three decades after her death, a book of recipes found among her belongings included a description of her survival strategies. “I am certain I will enter heaven,” she wrote. “From above, I will sustain the spirit of those who hide in order to remain truthful to themselves.”

American filmmaker Orson Welles, while shooting Touch of Evil (1958) with Charlton Heston and Janet Leigh (as well as appearances by Marlene Dietrich and Zsa Zsa Gabor), read “a small, strange book” called Pauahtun’s Revenge (1952), by Stewart McDuffy. He was fascinated by “the Mayan being that mutates incessantly and thrives when being exposed to radio airwaves.” When Universal Pictures decided to re-edit Touch of Evil, Welles said, “Pauahtun is allowing the heavens to loosen up.”

Eko is a Mexican artist who has illustrated an array of literary classics, from Cervantes’ Don Quixote to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.