In the summer of 1837, American painter and poet Christopher Pearse Cranch settled himself at his drafting table to complete a sketchbook—a comic really—his shorthand depiction of a new American way of thinking. Later published as Illustrations of the New Philosophy, it consisted of 28 caricatures that, according to Cranch, captured the seeds of a philosophy that had recently arisen in the outskirts of Boston: American Transcendentalism.

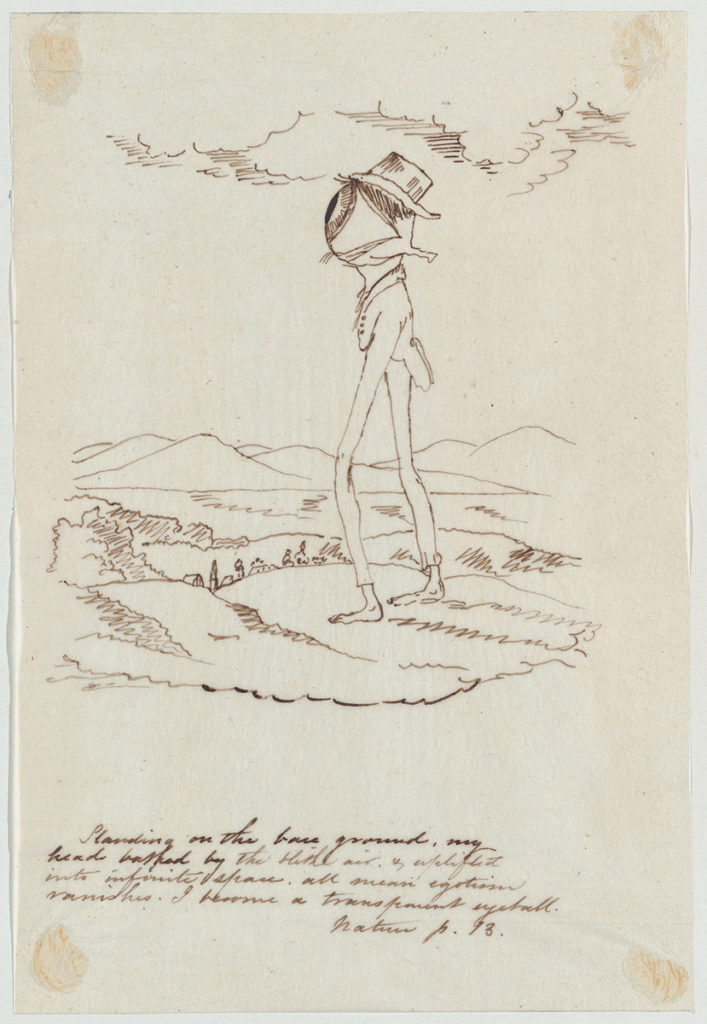

On the second page of his Illustrations, Cranch sketched an otherworldly image: a spindly legged being making his way up a New England hill, looming over the countryside, dressed in a waistcoat and hat, whose head had been replaced by a single probing eyeball. The drawing, no bigger than a sheet of paper, became Cranch’s most famous work for no other reason than its capturing the essence of a man who was arguably the most recognized American of the 19th century. This sauntering Cyclops was Ralph Waldo Emerson. Beneath the sketch, Cranch placed a caption referencing the following passage from Emerson’s Nature, published in 1836: “Standing on the bare ground,—my head bathed by the blithe air and uplifted into infinite space,—all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eyeball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.”

My first encounter with Nature and Cranch’s sketchbook did not yield particularly brilliant insights or transform me into a mystical seer. The prospect of becoming a transparent eyeball seemed unrealistic, undesirable, and unnecessary. I was just a kid with perfectly average eyesight. Why would I want to “see all,” every nuance but also every accident and torture, so clearly anyway? I could see just fine with my own two human eyes, thank you very much. More than anything, the eyeball on stilts struck me as arrogant and intrusive. Instead of being “part or particle of God,” the all-seeing eye looked like God himself. And I wanted no part of it.

As I’ve grown older, however, I’ve returned to Emerson and begun to appreciate the way that sight—or any mode by which one takes in the world—can determine what life is and what it can become. When we truly open our eyes, it is difficult, maybe even impossible, to fixate on ourselves. I say this as a novice. As it turns out, I am still not very good at seeing with my own two eyes: they usually catch sight of the most obvious and immediate aspects of life, which are often also the most petty. At 40, I am beginning to understand the urgency of what Emerson undertook, not really to see as the transparent eyeball does, but, more modestly, to see things through a bit more thoroughly, a bit more honestly. The revision of my world depends on it, and so does the meaning of my life.

The necessity of any revision, sadly, is often realized only after one’s world has come undone. That was the case for me at least. In the winter of 2019, I suffered three heart attacks and a cardiac arrest in the span of three months. After being shocked back to the world, and rushed to Tufts Medical Center, I was diagnosed with an “abnormal right coronary artery,” an innocuous-sounding term for a congenital heart defect that is one of the leading causes of sudden cardiac death in young athletes. I always thought I was fit and athletic. Maybe—but on the whole I’d just been extremely lucky.

Bypass surgery is a radical transformation of your body: your sternum is cracked, arteries are detached and reattached, and a small mechanical gadget is lodged in the heart of your being—literally. You will never be the same. This may be true, but now that I’ve experienced it, I think that the real transformation is one that forever alters the world in which you live. Curbs become annoying, stairs insurmountable; running becomes impossible, rest unavoidable; sleep becomes salvific; death becomes visible; life becomes precious. My recovery allowed me, after many years, to return to Emerson. I had some time to read. Emerson’s journals total 11,456 pages. It took me three months to work through them—roughly the time it takes a sternum to heal. I also had time to find my old copy of Cranch’s Illustrations. And time to think about the necessity and joy of seeing the world anew.

It took decades, but Emerson ultimately changed my life. More accurately, he changed my world, how I think it through, how I see it, even and most especially when I can’t see a way forward. Emerson’s angle of vision allows us to see beyond the immediate concerns of life to the truly important ones, to trump cynicism with insight, and to reframe a world shot through with boredom, injustice, and inescapable tragedy. To face the world with clear eyes, with Emerson’s eyes, is to cultivate what he would call a “fatal courage.”

I now think that Cranch’s famous cartoon of the transparent eyeball misses, or misconstrues, what is most essential about that passage from Nature. Cranch depicts the eyeball as striding triumphantly across a landscape in broad daylight, in midafternoon when the sun casts sharp shadows to the east. This, however, is not the real context for Emerson’s moment of sublime insight. In truth, it comes on the brink of night, in an empty Boston Common, on a depressing winter evening. It is only at moments of impending darkness that the value of sight is realized and enjoyed. “Crossing a bare common,” Emerson wrote, “in snow puddles, at twilight, under a clouded sky, without having in my thoughts any occurrence of special good fortune, I have enjoyed a perfect exhilaration. I am glad to the brink of fear.” What is it about taking in the world that can result in “a perfect exhilaration,” that can grant us escape from the snow puddles of our daily existence, that can make us “glad to the brink of fear?”