This essay is one of two that Joan Didion wrote for the Scholar. Read her second, “The Insidious Ethic of Conscience,” here.

Quite early in the action of an otherwise unmemorable monster movie (I do not even remember its name), having to do with a mechanical man who walks underwater down the East River as far as 49th Street and then surfaces to destroy the United Nations, the heroine is surveying the grounds of her country place when the mechanical monster bobs up from a lake and attempts to carry off her child. (Actually we are aware that the monster wants only to make friends with the little girl, but the young mother, who has presumably seen fewer monster movies than we have, is not. This provides pathos, and dramatic tension.) In any case. Later that evening, as the heroine sits on the veranda reflecting upon the day’s events, her brother strolls out, tamps his pipe, and asks: “Why the brown study, Deborah?” Deborah smiles, ruefully. “It’s nothing, Jim, really,” she says. “I just can’t get that monster out of my mind.”

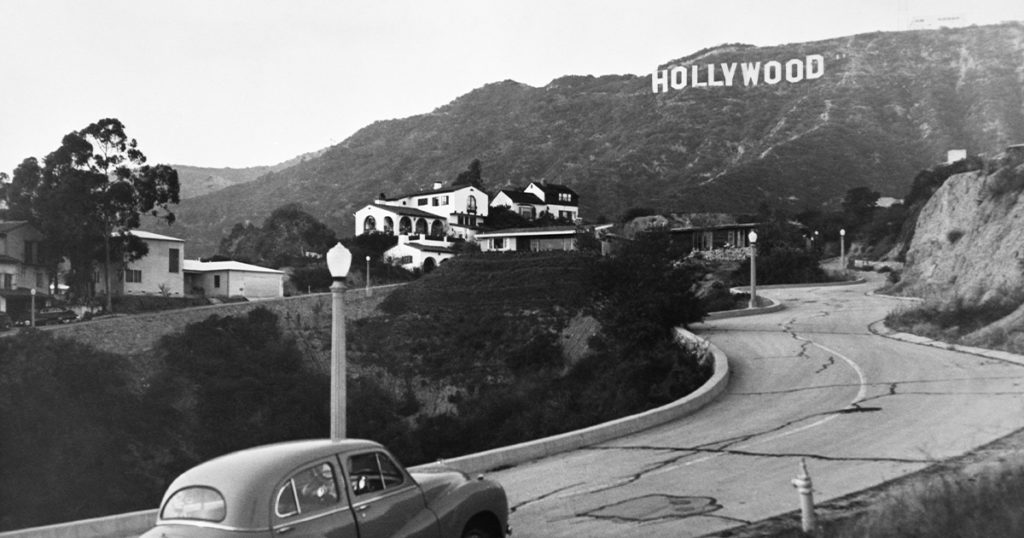

I just can’t get that monster out of my mind. It is a useful line, and one that frequently occurs to me when I catch the tone in which a great many people write or talk about Hollywood. In the popular imagination, the American motion picture industry still represents a kind of mechanical monster, programmed to stifle and destroy all that is interesting and worthwhile and “creative” in the human spirit. As an adjective, the very word “Hollywood” has long been pejorative, and suggestive of something referred to as “the System,” a phrase delivered with the same sinister emphasis that James Cagney once lent to “the Syndicate.” The System not only strangles talent but poisons the soul, a fact supported by rich webs of lore. Mention Hollywood, and we are keyed to remember Scott Fitzgerald, dying at Malibu, attended only by the gossip columnist Sheilah Graham while he ground out college-weekend movies (he was also writing The Last Tycoon, but that is not part of the story); we are conditioned to recall the brightest minds of a generation, deteriorating around the swimming pool at the Garden of Allah while they waited for calls from the Thalberg Building. (Actually it takes a fairly romantic sensibility to discern why the Garden of Allah should have been a more insidious ambiance than the Algonquin, or why the Thalberg Building, and Metro-Goldwyn Mayer, should have been more morally debilitating than the Graybar Building, and Vanity Fair. Edmund Wilson, who has this kind of sensibility, has suggested that it has something to do with the weather. Perhaps it does.)

Hollywood the Destroyer. It was essentially a romantic vision, and before long Hollywood was helping actively to perpetuate it: think of Jack Palance, as a movie star finally murdered by the System in The Big Knife; think of Judy Garland and James Mason (and of Janet Gaynor and Fredric March before them), their lives blighted by the System, or by the Studio—the two phrases were, when the old major studios still ran Hollywood, more or less interchangeable—in A Star Is Born. By now, the corruption and venality and restrictiveness of Hollywood have become such firm tenets of American social faith—and of Hollywood’s own image of itself—that I was only mildly surprised, not long ago, to hear a young screenwriter announce that Hollywood was “ruining” him. “As a writer,” he added. “As a writer,” he had previously written, over a span of ten years in New York, one comedy (as opposed to “comic”) novel, several newspaper reviews of other people’s comedy novels, and a few years’ worth of captions for a picture magazine.

Now. It is not surprising that the specter of Hollywood the Destroyer still haunts the rote middle intelligentsia (the monster lurks, I understand, in the wilds between the Thalia and the Museum of Modern Art), or at least those members of it who have not yet perceived the new chic conferred upon Hollywood by the Cahiers du Cinema set. (Those who have perceived it adopt an equally extreme position, speculating endlessly about what Vincente Minnelli was up to in Meet Me In St. Louis, attending seminars on Nicholas Ray, that kind of thing.) What is surprising is that the monster still haunts Hollywood itself— and Hollywood knows better, knows that the monster was laid to rest, dead of natural causes, some years ago. The Fox back lot is now a complex of office buildings called Century City; Paramount makes not forty movies a year but “Bonanza.” What was once The Studio is now a releasing operation, and even the Garden of Allah is no more. Virtually every movie made is an independent production—and is that not what we once wanted? Is that not what we once said could revolutionize American movies? The millenium is here, the era of “fewer and better’’ motion pictures—and what have we? We have fewer pictures, but not necessarily better pictures. Ask Hollywood why, and Hollywood resorts to murmuring about the monster. It has been, they say, impossible to work “honestly” in Hollywood. Certain things have prevented it. The studios, or what is left of the studios, thwart their every dream. The moneymen conspire against them. New York spirits away their prints before they have finished cutting. They are bound by cliches. There is something wrong with “the intellectual climate.” If only they were allowed some freedom, if only they could exercise an individual voice. . . . .

If only. These protests have about them an engaging period optimism, depending as they do upon the Rousseauean premise that most people, left to their own devices, think not in clichés but with originality and brilliance; that most individual voices, once heard, turn out to be voices of beauty and wisdom. I think that we would all agree that a novel is nothing if it is not the expression of an individual voice, of a single view of experience—and how many good or even interesting novels, of the thousands published, appear each year? I doubt that more can be expected of the motion picture industry. Men who do have interesting individual voices are even now making movies in which those voices are heard; I think, this past year, of John Huston’s brilliant The Night of the Iguana, of Elia Kazan’s ponderous but moving America America, and, with a good deal less enthusiasm for the voice, of Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove.

But it is not only the “interesting” voices who now have the opportunity to be heard. John Frankenheimer was quoted in Life recently as admitting: “You can’t call Hollywood ‘The Industry’ anymore. Today we have a chance to put our personal fantasies on film.” Frankenheimer’s own personal fantasies have included All Fall Down, in which we learn that Warren Beatty and Eva Marie Saint are in love when Frankenheimer dissolves to some swans shimmering on a lake, and, this year, Seven Days In May, which, in its misapprehension of the way the American power elite thinks and talks and operates (the movie’s United States Senator from California, as I recall, habitually drives a RollsRoyce), appeared to be fantasy in the most clinical sense of that word. Carl Foreman, who, before he was given a chance to put his personal fantasies on film, worked on some very good movies-High Noon and The Guns of Navarone, for two-this year released what he called his “personal statement”: The Victors, a phenomenon which suggests only that two heads are perhaps better than one, if that one is Foreman’s.

One problem is that American directors, with a handful of notable exceptions, are not much interested in style; they are at heart didactic. Ask what they plan to do with their absolute freedom, with their chance to make a personal statement, and they will pick an “issue,” a “problem.” The “issues” they pick are generally no longer real issues, if indeed they ever were—but I think it a mistake to attribute this to any calculated venality, to any conscious playing it safe. (I am reminded of a screenwriter who has just this year discovered dwarfs—although he, with the rest of us, must have lived through that period when dwarfs, those symbols of modern man’s crippling anomie, turned up on the fiction pages of the glossier magazines with the approximate frequency that Suzy Parker turned up on the advertising pages. There is a certain cultural lag.) Call it instead—this apparent calculation about what “issues” are now safe—an absence of imagination, a sloppiness of mind in some ways encouraged by a comfortable feedback from the audience, from the bulk of the reviewers, and from some people who ought to know better. Stanley Kramer’s Judgment at Nuremberg, made in 1961, was an intrepid indictment not of authoritarianism in the abstract, not of the trials themselves, not of the various moral and legal issues involved, but of Nazi war atrocities, about which there would have seemed already to be some consensus. (You may remember that Judgment received an Academy Award, which the screenwriter Abby Mann accepted on the behalf of all “intellectuals.”) Kramer and Abby Mann are now finishing Ship of Fools, into which they have injected “a little more compassion and humor” and in which they have advanced the action from 1931 to 1933—suggesting (to me, anyway) that they are about to register another defiant protest against the National Socialist Party. Foreman’s The Victors sets forth, interminably, the proposition that war defeats the victors equally with the vanquished, a notion not exactly radical. (Foreman is a director who at first gives the impression of having a little style, but the impression is entirely spurious, and prompted mostly by his total recall for old Eisenstein effects.) Even Dr. Strangelove, which does have a little style, is scarcely a movie of relentless intellectual originality; we have rarely seen so much made over so little. John Simon, in the New Leader, declared that the “altogether admirable thing” about Dr. Strangelove was that it managed to be “thoroughly irreverent about everything the Establishment takes seriously: atomic war, government, the army, international relations, heroism, sex, and what not.” I don’t know who Simon thinks makes up the Establishment, but, skimming back at random from “what not,” sex is our most durable communal joke; Billy Wilder’s One, Two, Three was a boffo (c.f. Variety) spoof of international relations; the army as a laugh line has filtered right down to Phil Silvers and “Sergeant Bilko”; and, if “government” is something about which the American Establishment is inflexibly reverent, I seem to have been catching some pretty underground material on prime time television. And what not. Except for such wild Terry Southern throwaways as the “mutiny of preverts,” Dr. Strangelove is essentially a one-line gag, having to do with the difference between all other wars and nuclear war. By the time George Scott has said “I think I’ll mosey on over to the War Room” and Sterling Hayden has said “Looks like we’ve got ourselves a shootin’ war” and the SAC bomber has begun heading for its Soviet targets to the tune of “When Johnny Comes Marching Home Again,” Kubrick has already developed a full fugue upon the theme, and should have started counting the minutes until it would begin to pall. What we have, then, are a few interesting minds at work; a great many less interesting ones. The situation in Europe seems to me to be about the same. Antonioni, in Italy, makes beautiful, intelligent, intricately and subtly built movies, the power of which lies entirely in their structure; Visconti, on the other hand, has less sense of form than anyone now directing. One might as well have viewed a series of stills, in no perceptible order, as his The Leopard. Federico Fellini and Ingmar Berg man share a stunning visual intelligence and a numbingly banal view of human experience; Alain Resnais, in Last Year at Marienbad and Muriel, demonstrates a style so irritatingly intrusive that it takes some time to realize that the style is all there is to the movie, that it intrudes upon a total vacuum. As for the notion that European movies tend to be more original than American movies, no one who saw Boccaccio ‘70 could ever again have the nerve automatically to modify the word “formula” with “Hollywood.”

So. With perhaps a little prodding from abroad, we are all grown up now in Hollywood, and left to set out in the world on our own. We are no longer in the grip of a monster; Harry Cohn no longer runs Paramount, as the saying went, like a concentration camp. Whether or not a picture receives an M.P.A.A. Code seal no longer much matters at the box office. No more curfew, no more Daddy; anything goes. Some of us do not quite like this permissiveness; some of us would like to find “reasons” why our pictures are not as good as we know in our hearts they might be. Not long ago I met a producer who complained to me of the difficulties he had working within what I recognized as the System, although he did not call it that. He longed, he said, to do an adaptation of a certain Charles Jackson short story. “Some really terrific stuff,” he said. “About masturbation. Can’t touch it, I’m afraid.”

I’m afraid he can’t. And I was reminded of the last line of that C.P. Cavafy poem in which the speaker—told and retold and eventually convinced that the barbarians who have haunted the city’s gates for decades are no longer there, suddenly vanished from the gates, mysteriously in retreat—finally murmurs with some regret: “And now what shall become of us without any barbarians? Those people were a kind of solution.”