Our Remedy

Quack Covid cures and New Age elixirs are just a 21st-century spin on 19th-century patent medicines

A few years ago, on a bright Saturday afternoon in March, my friends Chelsey and Kara and I went to the Silver Lake location of Los Angeles’s Moon Juice, which bills itself as a coffee bar, candy store, and apothecary rolled into one, selling various elixirs prepared by “a team of highly trained alchemists.” Drinking lattes infused with Power Dust and other “Alchemizers,” we watched as people streamed steadily in and out, buying $10 to $15 shots of juices and tonics with a variety of exotic ingredients: chijalit, black pepper oil, colloidal silver, ayurvedic mushrooms. Everyone seemed to be a regular; the employees knew the names of their customers’ pets.

The juices were all pre-bottled in a cooler (the blenders on display seemed like mere props) and had a chalky, earthy texture to them, except for the Golden Tonic, which tasted fairly rancid thanks to the inclusion of black pepper oil. Chelsey would later describe the bioactive almond milk mushroom latte—served to us in a paper cup with the words COSMIC IN A CUP stamped on the side—as tasting “like a hot puddle.”

The store also sells powders, oils, ointments, and potions, including Holy Yoni, a concoction of sweet almond oil, Bulgarian rose essential oil, schisandra berry extract, and Vitamin E. Daily application supposedly keeps one’s yoni “delicious and supple.” (Yoni is a Sanskrit word commonly translated as “womb.”) Most alarmingly, the display included a tester, boldly inviting the consumer: “Try me!”

At Moon Juice, everything promises something. The Power Dust offers “sustained energy and reduced fatigue,” the Dream Dust a “calm” mood, and the Spirit Dust a “positive” one. One of Moon Juice’s bestselling products, SuperYou, sells for $49 a bottle and is described this way on the company’s website:

SuperYou is your daily multi-adaptogen to unstress. 2 caps a day keep the stress away. Our clinical strength, time-release formula helps regulate cortisol for proactive and reactive stress support.* Four potent adaptogens traditionally used in Ayurveda and TCM alleviate the emotional, mental, hormonal, and physical manifestations of stress.*

When the stress response activates, all four adaptogens help regulate spiked cortisol. Then Ashwagandha comes in to reduce irritability.* As stress continues, energy gets depleted, and Rhodiola helps reduce fatigue and increase endurance.* Prolonged periods of stress can impact hormones and skin, so Shatavari supports healthy hormonal balance and libido while Amla helps protect skin from oxidative stress and accelerated aging.*

Commit daily for life-changing results.* Recurring subscription orders are fulfilled with compostable pouches to refill your original bottle.

Of these nine sentences, six end with an asterisk, but you have to scroll down to the bottom of the page—past the customer reviews (“I feel less stress when I take Super You. I take it before I start my job Monday thru Friday. I use[d] to feel aches in my neck while working but not anymore”), and beneath the information on subscribing for a monthly bottle, links to other bestsellers (SuperHair, SuperBeauty), the FAQ (“How does SuperYou work,” “Can I take all the Supers together?”), and even the social media buttons—before you finally get to an explanation for the asterisk: “These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.”

The dietary supplement industry, of which Moon Juice is just one small portion, sells (according to one estimate) some $35 billion in products per year to consumers in the United States alone. Brands with names like Nature’s Bounty and Purity Products advertise everything from squid oil to chromium to the monkey head mushroom, and all of it is made possible by those two sentences—repeated over and over again, printed on millions of labels in tiny fonts, ritually intoned until their meaning has been obliterated.

According to one financial analysis, the Covid-19 pandemic has had a “staggering” impact on the industry, which grew 26.9 percent in 2020. In addition to dietary supplements, new and strange treatments have become more and more common in the age of perpetual pandemic. Both hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin have been used for years (the former primarily to treat malaria and the latter for parasites), but both have been advanced as possible cures for Covid-19, despite all prevailing scientific evidence. No study yet has found any definitive benefit from either drug, and both come with serious side effects. Hydroxychloroquine has been shown to cause heart problems, liver inflammation, and kidney failure when improperly taken outside of prescribed settings. And in September, the FDA reported more than four dozen cases of poisoning linked to ivermectin, just as doctors in Oklahoma were warning that ivermectin overdoses were straining the state’s already overburdened hospitals. A few weeks later, the New Mexico Department of Health reported two deaths that its acting cabinet secretary David Scrase said were linked to ivermectin toxicity.

None of this has stopped the use of these drugs, nor the bizarre and fantastical promises that these useless remedies can be made at home with ordinary ingredients. A viral TikTok video last summer promised that hydroxychloroquine could be made using citrus peels; it cannot. Though, presumably, this homemade citrus concoction is as effective as prescription hydroxychloroquine in combating Covid-19.

Although promises of Moon Juice or off-brand Covid treatments may be new to most of us, the thinking behind them—there’s a secret cure-all home remedy the medical establishment doesn’t want you to know about—is nothing new. So-called patent medicines have been a part of American culture since before its founding; widespread and unregulated, they rarely did what they advertised, and their effects could be unpredictable—even deadly. In 1904, Mary A. Bispels of Philadelphia, died at 18 from kidney and heart failure as a result of taking another quack substance, Orangeine, the same curative that killed Frances Robson of Chicago a year later. That very same year, the world was shocked when London sisters Constance Adelaide and Dorothy May Sheppard, aged three and two, were given Liquozone (originally titled Liquid Ozone), which turned out to be highly diluted sulfuric oxide instead of liquefied oxygen. Both died from exhaustion, vomiting, and diarrhea. These were some of the more famous cases; it’s impossible to say how many deaths in total were caused by these and other “cures.”

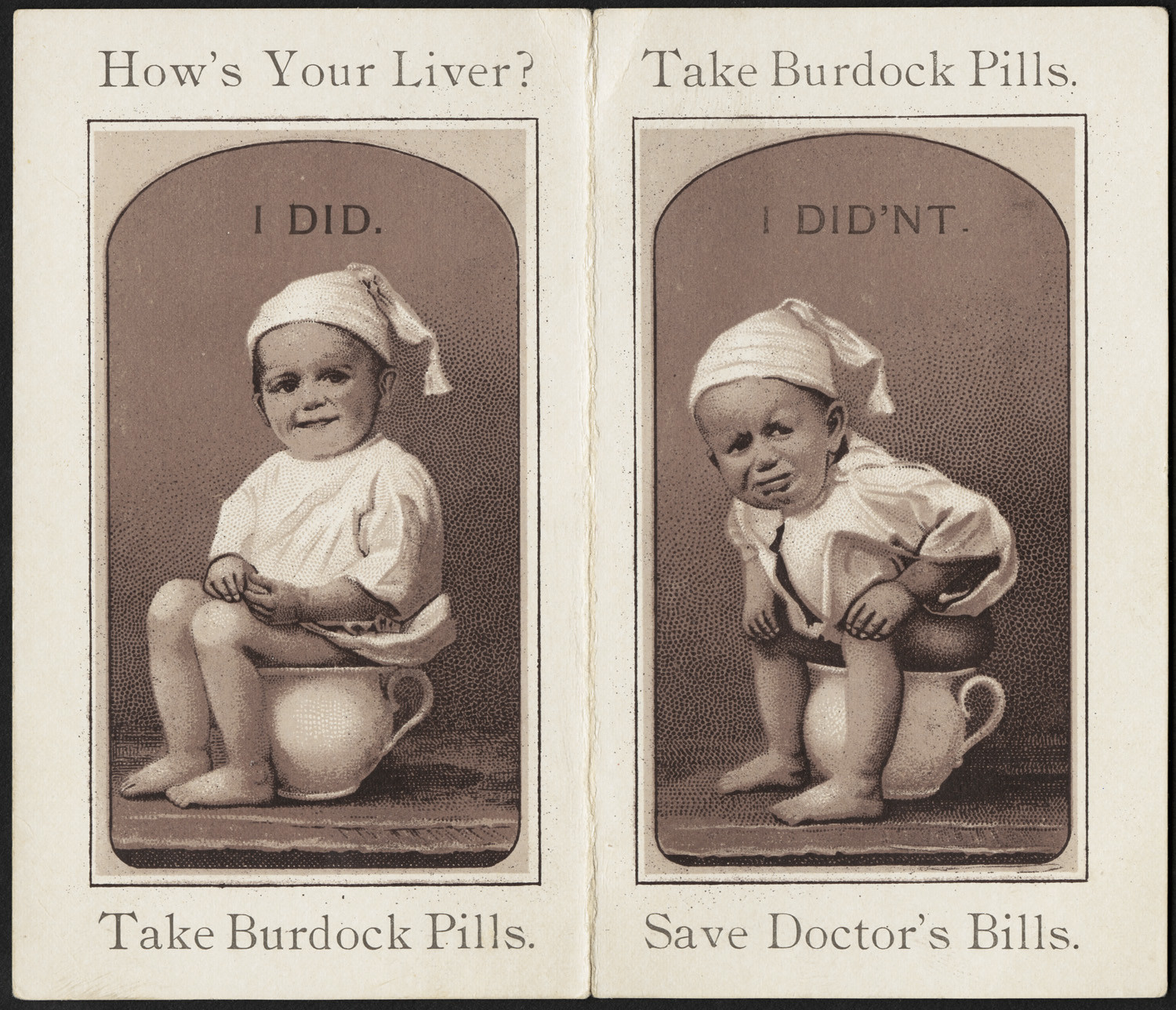

Patent medicine has its roots in the English medicine of the 17th and 18th centuries, when products like Anderson’s Pills, Daffy’s Elixir, and other concoctions flooded the marketplace. Named originally for the “letters patent” granted by the English government, patent medicines were also frequently referred to as “nostrums,” from nostrum remedium (“our remedy”), which mostly were not much more than alcohol-based laxatives flavored with roots, herbs, and other botanicals.

Always popular in Great Britain, patent medicines comfortably made the journey across the Atlantic, becoming even more widespread. As they expanded in popularity, patent medicines were prepared with more and more daring ingredients and were prescribed to treat a wider range of ills. Some of the concoctions were placebos. Most were a proprietary mixture of odd botanicals and herbs, calculated mixtures of sweet and bitter flavors meant to stimulate a response sufficient enough to dupe the patient into thinking some change had taken place. Others, though, added to this mixture high levels of alcohol, diluted sulfuric or hydrochloric acids, habit-forming narcotics like opiates, or outright poisons. One wildly successful example was Swaim’s Panacea (“A Recent Discovery for the Cure of Scrofula or King’s Evil, Mercurial Disease, Deep-Seated Syphilis, Rheumatism, and All Disorders Arising from a Contaminated or Impure State of the Blood”), which consisted primarily of sarsaparilla syrup, oil of wintergreen, and mercury. William Swaim of Philadelphia sold his panacea for an outrageous $3 a bottle (about $95 in 2022 dollars), but was successful enough that, by his death in 1846, he was worth more than a million dollars. In advertisements, Swaim touted, among other success stories, the case of Nancy Linton, who’d nearly died of scrofula before turning to Swaim’s. He used new lithograph technology to represent her “actual appearance after having been Cured,” though her “Cured” state shows the gruesome side effects of mercury poisoning.

Patent medicines were attractive simply because they could be acquired without a prescription, and thus were an easy shortcut. Particularly when it came to sexually transmitted diseases, or the ever-amorphous “female troubles,” avoiding a doctor’s visit spared patients shame and embarrassment.

Although scientifically dubious in the extreme, patent medicines were advertised as part of a medical protocol instead of as folk remedies or sympathetic magic. The 18th and 19th centuries saw an explosion of scientific knowledge and the professionalization of medicine, even as the causes of many diseases still remained stubborn mysteries. As physicians worked the slow process of the scientific method, trying to understand and eventually cure disease, quack peddlers filled the gap.

The problem was not the spirit of inquiry, but rather that the tools at the disposal of those early doctors were insufficient to penetrate the very complicated workings of the body and its diseases. The explosion of patent medicines in America was a result of impatience—or understandable desperation—when the scientific method didn’t yield easy results. As James Harvey Young wrote in The Toadstool Millionaires: A Social History of Patent Medicines in America before Federal Regulation,

Many physicians became disillusioned when biological research seemed to lead not to universal laws, like gravitation, but only to more complications and greater confusion. Anxious to get their single explanations for all disease, they did so by neglecting the scientific method, or by following it only a short way. They built vast theoretical medical schemes by speculative logic. The 18th century was a time of system-making.

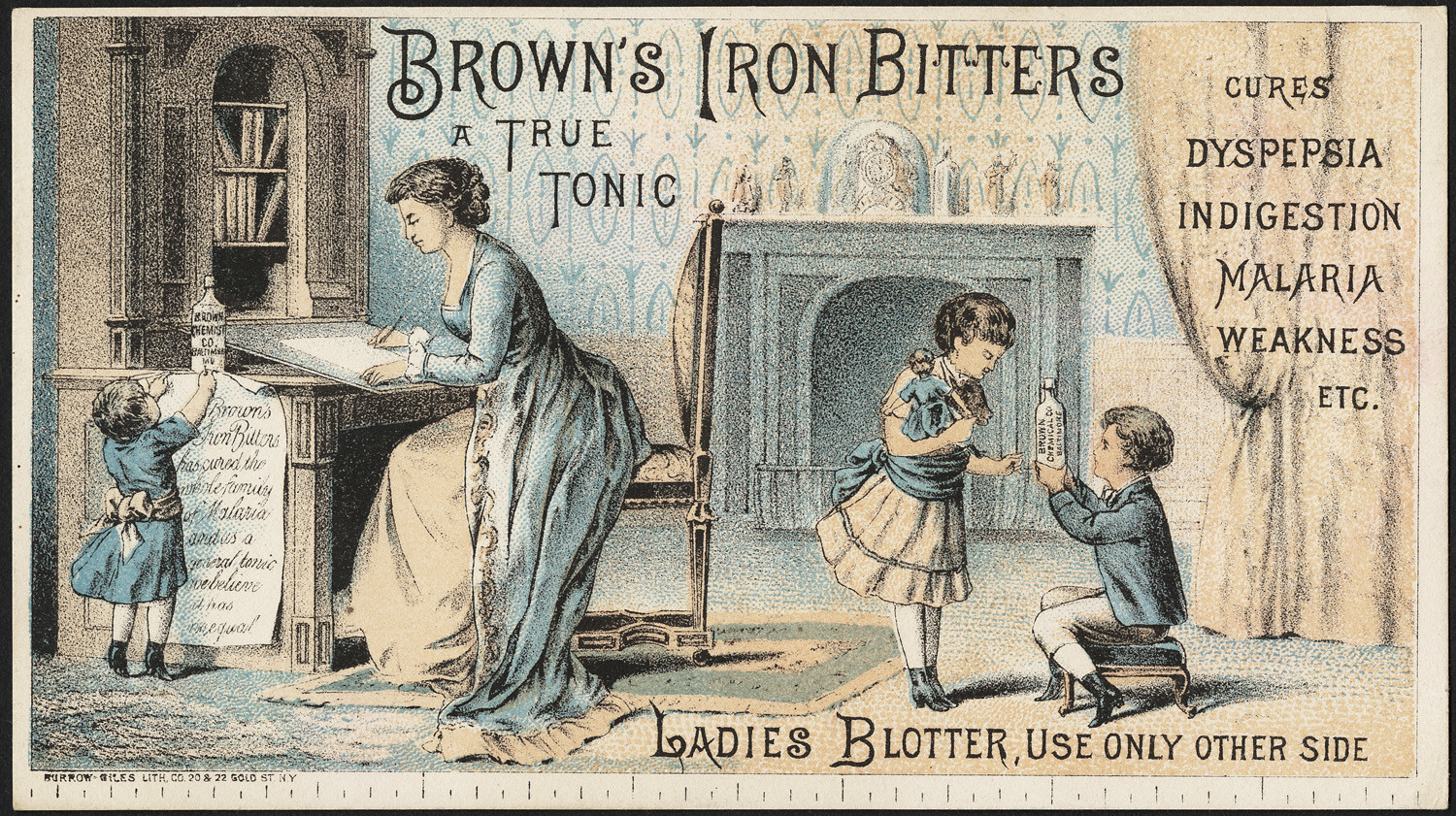

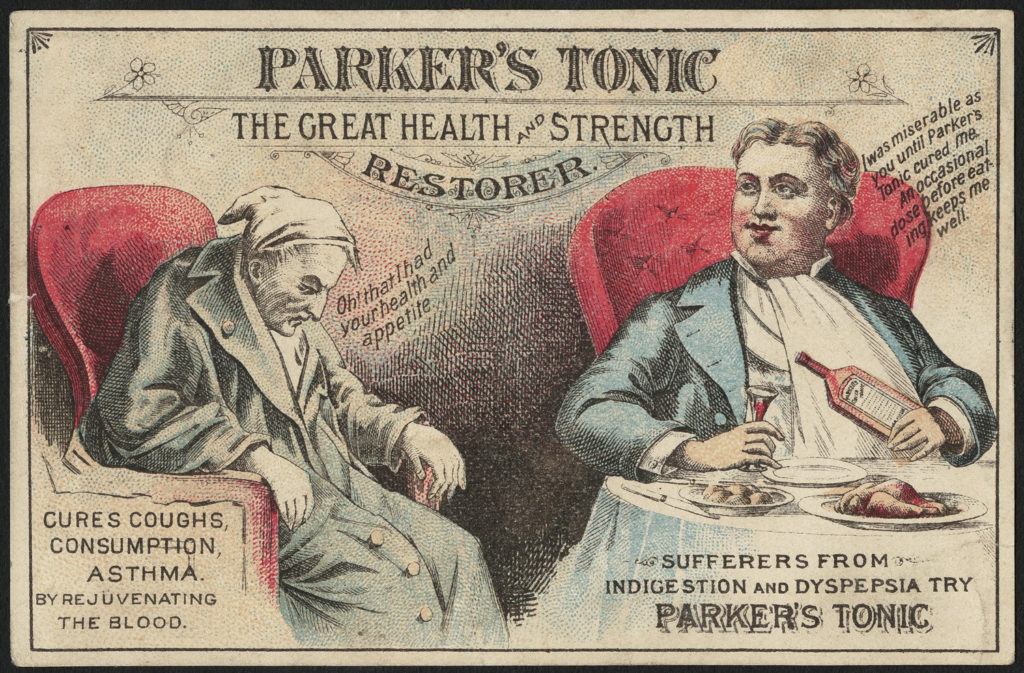

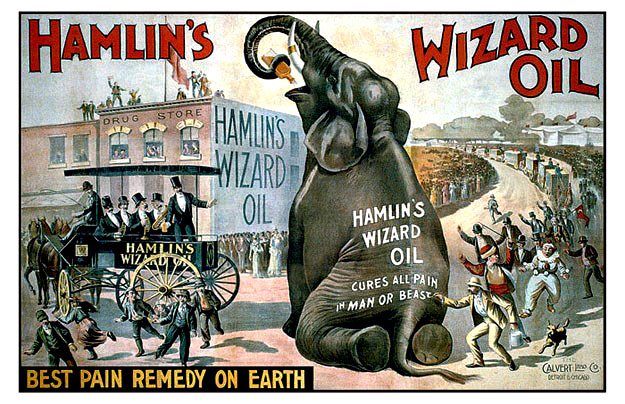

In addition to partaking in that grand old American tradition of shortcuts and half-assery, nostrum quacks reflected other aspects of burgeoning American capitalism. Patent medicine indulged a flair for advertising, with bold typography, testimonials from eminent doctors, the latest in lithography and other printing techniques. Those who peddled them represented, in a perverse way, the American Dream: these were individual businessmen pulling themselves up by their bootstraps, while taking on the medical establishment and big business. That their dream was based on (literal) poison was, in the grand scheme of American commerce, of minor consequence.

As the Australian magazine The Lone Hand would describe the situation at the dawn of the 20th century, “America is the centre of medical charlatanism and pharmaceutical fakery. Nowhere else in the world is mankind so prone to worship new and strange medicines. Nowhere else is there such a host of patriots eager to cater for the wants of their credulous countrymen.”

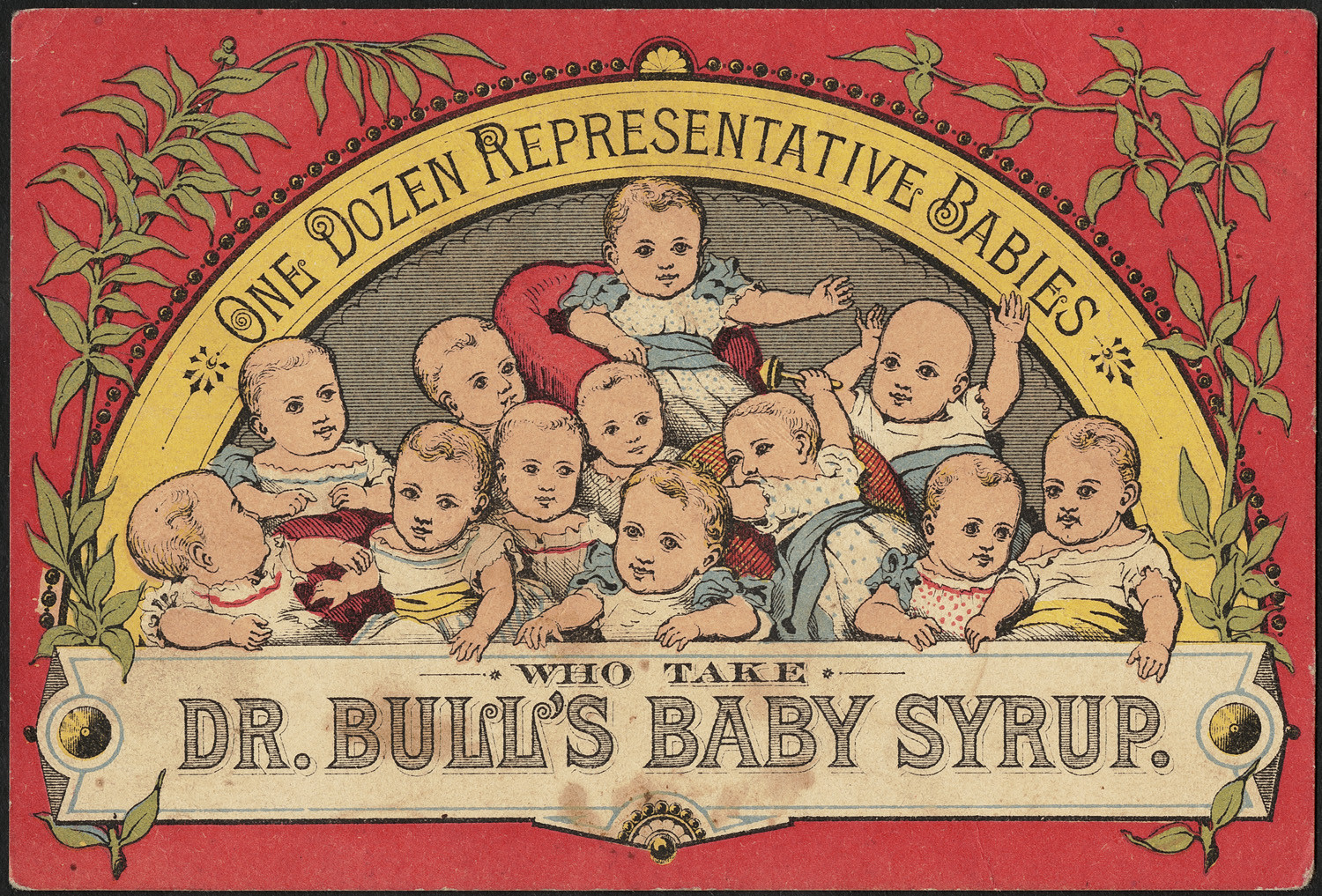

Attempts were made throughout the 19th century to regulate the problem of patent medicines. The physician Horatio C. Wood Jr. was among many who targeted the dangerous fraud known as “soothing syrups,” formulas for infants that depended in large part on morphine. “The immediate deaths which have followed an overdose of some opium-containing ‘soothing syrup’ are numerous enough,” he wrote, “but the thought of the hundreds of children condemned from the cradle to a life of invalidism, to which the grave is preferable, by the formation of a morphine habit from which the delicate nervous system is never able to recuperate, is horrible.”

But many of the attempts to establish regulatory bodies floundered in the various states where they were tried. Dr. Harvey Washington Wiley, who in 1883 became head of the Bureau of Chemistry of the Department of Agriculture (the FDA’s predecessor), attempted to publicize the danger of food adulterants and other consumer hazards, but largely failed to persuade the public or his government. Writing in the 1930s, the historian C. C. Regier notes that between 1879 and 1906, 190 measures were introduced in Congress with the aim of regulating consumer drugs and food products. Of those 190, eight became law. Some of the rest passed the Senate and not the House, or vice versa; some barely made it out of committee; and more than 140 were never seen again after their introduction. Somewhat acidly, Regier comments that there “seemed to be an understanding between the two houses that when one passed a bill to repress food adulteration the other would see to it that it was buried.”

A significant part of the problem was that newspapers, many of which relied on revenue from patent medicine advertisements, were bound by the so-called “red clause,” a line in their contracts (printed in red) declaring the contract void should legislation regulating food and drugs ever be passed. The press thus exerted little public pressure for reform.

Meanwhile, business continued to grow, as did its inherent problems. The pharmacists profiting from patent medicines knew full well they were frauds, and in some cases were perfectly willing to admit this in public. The Economical Drug Company of Chicago posted a sign in its window that read, in part, “PLEASE DO NOT ASK US WHAT IS ANY OLD PATENT MEDICINE WORTH? For you embarrass us, as our honest answer must be that IT IS WORTHLESS. If you mean to ask at what price we sell it, that is an entirely different proposition.” Nonetheless, even such champions of truth could not afford to stop selling these worthless drugs, as they accounted for a third of the Economical Drug Company’s business.

By the turn of the century, the rise of muckraking journalists shifted the fourth estate’s allegiances when it came to the problem of patent medicine fraud. None were so comprehensive or strident as Samuel Hopkins Adams, who in 1905 wrote an 11-part series for Collier’s magazine on “The Great American Fraud.” Adams was only 34 when he wrote the series, which remains one of the landmarks of progressive muckraking, relying on original research, chemical analyses of the various nostrums and patent medicines, and the writer’s ability to get candid confessions from some of the worst nostrum peddlers.

“The Great American Fraud” opens with a sweeping, damning diagnosis of the American medical condition:

Gullible America will spend this year some seventy-five millions of dollars in the purchase of patent medicines. In consideration of this sum it will swallow huge quantities of alcohol, an appalling amount of opiates and narcotics, a wide assortment of varied drugs ranging from powerful and dangerous heart depressants to insidious liver stimulants; and, far in excess of all other ingredients, undiluted fraud.

Focusing on potions with bizarre names such as Dr. W. O. Bye’s Cancer Cure, Liquozone, Dr. Williams’ Pink Pills for Pale People, and Rupert Wells’ Radiatized Fluid, Adams excoriated an industry wreaking dangerous havoc on an unsuspecting public.

Adams leveled accusations in nearly all directions. Eminent physicians and doctors, who lent their names in testimonials but knew nothing of the compounds they were endorsing. The government, particularly the Post Office, which declined to prosecute fraudulent products sent through the mail (though he did commend them for cracking down on purveyors of “weak manhood” remedies), and the Patent Office, which issued trademark registration to nostrums and thereby made something of a mockery of its entire office. State health departments, such as New York’s, which had found that some catarrh powders contained dangerous amounts of cocaine but then subsequently buried the study.

But most of all, Adams targeted the proprietors themselves. Several parts of his exposé focused on individual patent medicines, such as Peruna, the deadly Orangeine (its active ingredient, acetanilide, responsible for multiple deaths), and Dr. Bull’s Cough Syrup (active ingredient: morphine). Peruna’s creator, Dr. Samuel Brubaker Hartman, admitted to Adams that it was entirely a placebo: “They see my advertising. They read the testimonials. They are convinced. They have faith in Peruna. It gives them a gentle stimulant, and so they get well.” (Peruna’s active ingredient, as it turned out, was alcohol, and at 28 percent alcohol by volume, it was far more potent than anything short of hard liquor.) Adams contrasted Dr. Bull’s Cough Syrup’s advertised claims (“There is no case of hoarseness, cough, asthma, bronchitis … or consumption that can not be cured speedily by the proper use of Dr. Bull’s Cough Syrup”) with a response to an inquiry he received directly from the company (“We do not claim that Dr. Bull’s Cough Syrup will cure an established case of consumption. If you have gotten this impression you most likely have misunderstood what we claim. … We can, however, say that Dr. Bull’s Cough Syrup has cured cases said to have been consumption in its earliest stages”). And Adams included, damningly, a reproduction of a coroner’s report that revealed the nostrum to be the cause of death in a two-year-old.

Adams’s exposé of patent medicines, along with others in similar journals, finally spurred Congress to act. On June 30, 1906, a year after Adams’s articles were published, Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act—alongside the Meat Inspection Act, inspired by Upton Sinclair’s publication of The Jungle just four months earlier. Adams himself had a hand in drafting the legislation, and was brought to Congress to testify on behalf of the legislators pushing the bill.

But the bill was more or less undermined by manufacturers’ lobbyists, and went into effect with no teeth. It forced nostrum makers to label dangerous ingredients, but didn’t bar their use or regulate their dosage. (In the 1916 case United States v. Forty Barrels and Twenty Kegs of Coca-Cola, the Supreme Court affirmed that although Coca-Cola had to label the “habit-forming” ingredient of caffeine on their bottles, it didn’t have to reduce the amount of caffeine.) Harvey Washington Wiley, who had worked feverishly as head of the Bureau of Chemistry to regulate dangerous food additives for more than two decades, eventually resigned in protest over lax enforcement.

“The statute which required seventeen years of unremitting effort to place upon the books is, so far as many important forms of adulteration are concerned, practically an inert machine,” Adams wrote in 1910. “It is being destroyed by the old allied forces of fraud and poison.” Frustrated, he emulated Sinclair and wrote a novel about patent medicines, The Clarion. Published in 1914, it failed to have much popular or political impact. The general public, it would seem, considered the matter settled.

Recent historians suggest that the law did have an effect on the industry, though not necessarily (or entirely) for consumer protection. As Donna J. Wood notes:

Many of today’s reputable pharmaceutical manufacturers existed at the turn of the century, but they did not control the market for medicines, nor were they the focus of the controversy that erupted. Public attention focused instead on the widespread use of patent medicines (more accurately, proprietary remedies), produced and sold by a multitude of independent ‘medicine men.’

The Pure Food and Drug Law—which was rigorously opposed by the American Proprietary Association (a patent medicine trade group)—was in fact supported by many more traditional food and drug businesses, including H. J. Heinz. By turning the government’s attention to smaller, independent operators, the Pure Food and Drug Act worked to consolidate the market in the hands of larger corporations.

The end result of the law was less about consumer protection and more about the movement of the trade away from individual proprietors. Wood notes that when it comes to drugs and whiskey,

tentative evidence suggests that it was the larger, better-capitalized, well-established, more heavily industrialized firms that felt the threat of many small, aggressive competitors and sought to prevent erosion of their market positions by having these competitors’ products declared adulterated, misbranded, or hazardous to human health.

In the early years of the patent medicine craze, individuals could sell whatever the public would buy for whatever the market would bear. By the 20th century, however, this more naïve version of American capitalism was run out of town by a corporate model that, as it happened, would continue peddling the same frauds unabated for several more decades.

It took 32 years for Congress to pass a second law, the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which in 1938 banned the most dangerous of food additives and barred the most egregious frauds and duplicitous claims. The patent medicines that survived tailored back their promises (as in the case of companies like Vick’s Vapor Rubs, Bayer Aspirin, Phillip’s Milk of Magnesia) or rebranded as beverages instead of medicine (as with Coca-Cola, 7-Up, and Angostura Bitters). But they remain with us, legacies of the days in which flavored alcohol and unregulated opiates could offer cures for everything from “that certain disease” to cancer, from “female troubles” to constipation.

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act was amended piecemeal through the decades as new issues arose, but it wasn’t until 1994 that the immortal words at the bottom of Moon Juice’s website and so many others—“These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease”—became codified into law with the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act. It gave supplement makers nearly unchecked freedom to put anything on the market so long as it carried the FDA’s disclaimer.

There have been attempts to regulate supplements, particularly when they’re found to be fatal, as was the case with ephedra in 2004. But that battle took nearly eight years, and multiple deaths were attributed to the weight-loss drug before it was finally banned. As the law is written, the FDA is obligated to prove a supplement is dangerous, rather than the manufacturer being obligated to prove it is safe.

In some ways, we brought this on ourselves. The consumer appetites that made patent medicines an economic juggernaut 200 years ago have not gone away; we still want the quick fix, the panacea, the little boost. And the worldwide confusion, anxiety, and uncertainty that have accompanied the Covid-19 pandemic only exacerbate our need for something that gives us a sense of control, however illusory. This is, finally, what quack nostrums truly offer us: not a cure for the disease itself, but a cure for the terror of not knowing.

Just as the old patent medicines relied heavily on branding and marketing, so too do today’s panaceas rely heavily on evoking a mood and experience that make them seem essential. Supplement companies these days spend more on advertising than they do on the products themselves: a 2018 study found that dietary supplement companies spent $900 million that year on marketing. Sure, you’re less likely to encounter dangerous substances these days, but what you end up paying for is the placebo effect: clinical-looking vials that seem scientific and cutting-edge, or—as in the case of places like Moon Juice—come adorned with soft, muted colors and beautiful fonts, all peddled by Instagram influencers and podcast hosts.

I felt mildly nauseated on the afternoon I spent among the well-curated shelves and warm color palettes, ayurvedic mushroom tinctures and activated cashew smoothies—a feeling that got steadily worse and persisted for the rest of the weekend. Perhaps, I find myself wondering now, all those expensive tinctures and dusts do nothing beyond tearing up your gut, giving you the illusion of health by merely emptying you out. But—I hasten to add—such statements have not been evaluated by the FDA.