Building Up and Breaking Down

What happens when the structures we erect plunge us into despair?

Bold Ventures: Thirteen Tales of Architectural Tragedy by Charlotte Van den Broeck (trans. from the Dutch by David McKay); Other Press, 304 pp., $27.99

In the 1860s, the Austrian military engineer Karl Pilhal struggled to anchor a new army barracks in the soupy ground beside the Danube Canal in Vienna. He dug down nearly 15 feet for the foundations. He called for a nearby graveyard to be churned up, then carted in the bone-rich earth to add to the silt. The towers of the Kronprinz Rudolf (later Rossauer) Barracks rose, forbidding and unshakable, across from the city’s Augarten park. Yet they hid an embarrassing design flaw. For the 2,400 soldiers quartered there, Pilhal had specified only four toilets. He was said to have killed himself in shame over his mistake.

The story is almost certainly apocryphal—a quick Google search reveals that Pilhal retired in 1871 and died seven years later—but in Bold Ventures, Belgian poet Charlotte Van den Broeck is less interested in separating myth from truth than in probing the relationship between artistic creation and its constant shadow: failure. A blend of architectural history, memoir, and philosophical meditation, the book tracks Van den Broeck’s odyssey to visit 13 buildings that either drove their designers to kill themselves or were rumored to have done so. Along the way, she wrestles with her own vocation as a writer, her dread of failure, and the need to, as she puts it, “leave a superior kind of debris.”

The book’s organizing principle makes for an idiosyncratic survey, ranging from Malta to Colorado. A few days before his suicide in 1667, Francesco Borromini smashed up his workshop and shredded his drawings, a breakdown brought on by the strain of completing the Church of San Carlo alle Quattro in Rome, his life’s work. Centuries later, the Belgian modernist Gaston Eysselinck (1907–1953) killed himself after designing the central post office for the city of Ostend. He was hotheaded and a perfectionist, like Borromini, and the post office project was fraught. Eysselinck argued with both the contractors and his clients and eventually was himself banned from the building site. But creative frustration didn’t cause him to take his own life: he was in despair over the death of his lover from cancer. His final design was for her gravestone.

What drew Van den Broeck to these dead architects? In a world where “everyone’s always looking for admiration” for “petty” things, she writes, architects

at least make grand gestures, playing for mortal stakes, on a massive scale, in the public eye, creating tangible surfaces and masses that impose proportion and outwit indifference. Architects who fail in public space fail in plain sight of thousands of onlookers, and their failure lives on for a long time. … Their audacity must be too much for some people to bear.

Literary creation is more private than architecture, but the stakes are hardly lower for Van den Broeck. After experiencing the first glimmers of public recognition for her poetry, she tells us, “I knew one thing for certain: this was too much. Writing and leading a full life, I can’t do both.” Instead of having normal relationships, she writes, “I recruit accomplices in my self-destruction.” Even more than failure, she fears being mediocre, “a state that cannot be transcended,” which sometimes stops her from writing anything at all. “I can’t make concessions,” she says.

This is a romantic, even melodramatic conception of what it means to be a writer, and to enjoy the book, a reader has to indulge it at least a little. Fortunately, the self-seriousness of Bold Ventures is relieved by moments of mordant humor, such as Van den Broeck’s recounting of a series of bizarre accidents at the cursed swimming pool in her hometown—a girl’s ponytail getting trapped in a drain, a power outage that leaves swimmers flailing in the dark, the water turning milky for mysterious reasons.

The book also has a chorus: the people the author meets on her travels, who casually poke holes in her inflated ambitions. Most of all, Giulia, her landlady in Naples, where she goes to search out the ghost of Lamont Young, a visionary Scottish-Italian architect. Giulia reluctantly trudges up Monte Echia with her guest to see the dilapidated villa where Young died in 1929. “That hovel? That’s what you’re planning to write a book about?” she demands when they arrive. “Absolutely no one will read it! Besides, it’s not normal for a young woman to be so obsessed with death. You shouldn’t be making up books, you should see a psychiatrist.”

Van den Broeck worries that she’s offering an explanation or even justification for suicide, by tying it to her fear of failure, when she’s aiming to be compassionate. In a bookstore, she reaches for John McPhee to learn “how to be less present” in her writing. She also buys the complete works of Anne Sexton. The meaning is clear: she can only be the type of writer she is.

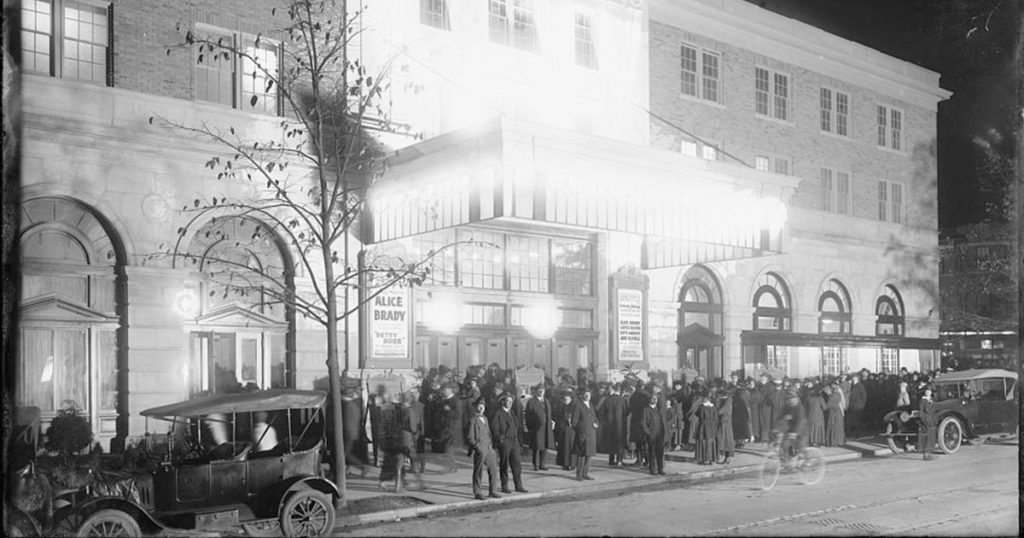

But her writing isn’t lacking in compassion, especially in the book’s most harrowing chapter. In January 1922, a blizzard hit Washington, D.C. More than two feet of snow piled up on the roof of the Knickerbocker Theatre in the Adams Morgan neighborhood, and it collapsed during a showing of the comedy Get-Rich-Quick Wallingford. Ninety-eight people died and another 133 were injured, some gravely.

The theater’s young architect, Reginald Geare, went into a state of shock. He did not proclaim his innocence, but “revisited every decision, redrew the plans and then redrew them again to make sure” he had not miscalculated. “Night after night, he rebuilt the theatre from the ground up, stone by stone.” He could not figure out what had gone wrong. An investigation later found construction errors with the main roof truss, attributable in part to Geare. Five years after the tragedy, Geare, a broken man, ended his life.

Any authentic act of artistic creation requires putting some of oneself on the line. Van den Broeck says she “take[s] my life in my hands” to write, and compares it to climbing a rope or holding her breath underwater. But words on the page are weightless; bricks and beams are heavy. Some stakes, it turns out, are more mortal than others.