The Goddess Complex

A set of revered stone deities was stolen from a temple in northwestern India; their story can tell us much about our current reckoning with

In January 2020, in a remote, arid corner of southwestern Rajasthan, I was squeezed in the back seat of a Toyota SUV with my five-year-old son and Prachi and Prince Ranawat, a sister and brother, ages 23 and 18, from a dot of a town called Parsad. On a motorcycle, their father, Gajeraj Ranawat, followed. The driver propelled us along a parched roadway overgrown with candelabra cactus and bougainvillea, its pink and white flowers covered with dust. Sprays of yellow oleander spilled onto our path, and the screeches of langur monkeys echoed in the distance.

The family was leading me to a temple complex that once sheltered the so-called Tanesar sculptures, a set of 12 or more stone figures dating to the sixth century. Naturalistic, slender, luminously jadelike, and around two feet high, most of the sculptures depict mother goddesses (matrikas), with some holding a small child. Attendant male deities were also part of the set. According to art historians, the Tanesar figures were sculpted by an itinerant artisan guild as a form of patronage to local rulers. The sculptures were associated with fertility, but they were also linked with terrifying aspects of the all-encompassing mother goddess Devi in her manifestations as Kali and others—dangerous, destructive yoginis whose power eclipsed that of all the male Hindu gods combined. Over time, fearful villagers buried the sculptures in a field, hoping to contain their energy. But later, when the sculptures were feared no more, they were dug up and dragged to a small shrine to Shiva. There they were given pride of place in an enclosure to the side of the structure. At some point in their history, the figures became focal points for tantric prayer, with worshippers seeking a disintegration of the physical self to meld into universal consciousness.

For many years, the Tanesar sculptures remained an integral part of local religious life—unknown to anyone else. But around 1957, a prominent archaeologist in Rajasthan discovered the figures and then published an article about them in an Indian art history journal, making an inner circle of Indian and Western art historians aware of their existence. What followed was a story all too familiar in the world of art and antiquities: sometime around 1961, most of the Tanesar sculptures were stolen. From what I’ve been able to piece together, they were smuggled across the countryside, down to what was then Bombay, across the Indian Ocean and the Atlantic—to Liverpool and then New York. The American art dealer Doris Wiener, who ran a gallery on Madison Avenue, had a hand in the export of several of them. Another landed at the British Museum through a separate channel.

Very soon, the mid-century art world became enchanted with the sculptures. Art dealers, collectors, and museum directors eyed their potential worth. In 1967 and after, Wiener sold six or more sculptures from the set, for the equivalent of $80,000 each in today’s dollars, to curators and collectors who had more than an inkling of the dubious circumstances of the objects’ traffic. She sold one to Blanchette and John D. Rockefeller III and another to the Cleveland Museum of Art. The others passed from hand to hand before arriving at the world’s most revered collections of South Asian art, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA).

Mother Goddess (Matrika), previously on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, was seized in August 2022 by the office of the Manhattan DA. (Courtesy of the author)

On August 30, 2022, the office of the Manhattan District Attorney, Alvin L. Bragg, issued a search warrant for one of the sculptures, called Mother Goddess (Matrika). At the time, it stood on a pedestal in the coolly lit gallery 236 of the Florence and Herbert Irving Asian Wing at the Met. The sculpture was seized, part of a sweeping sting targeting works acquired by Wiener as long as 60 years ago. Over the past decade, more than 4,500 allegedly trafficked antiquities have been confiscated by the office of the Manhattan DA. Instrumental in this work has been Assistant DA Matthew Bogdanos, a Marine colonel who led a government investigation into the looting of the Iraq Museum in 2003. Of those antiquities recovered by the Manhattan DA, nearly half have been returned to 24 countries of origin, with India receiving the largest share.

So many sculptures seized and sent home, each with its own story. It can be hard to see why any one of those stories matters in the particular. The repatriated artifacts are not as well known as the Benin Bronzes, for example, plundered from West Africa by British colonists, or the Parthenon marbles, removed by Lord Elgin in the early 1800s and now on display at the British Museum. They are not symbols of empire, nor are they the spoils of war. Rather, they are emblems of something more banal and arguably more pernicious—the practice of mid-century antiquities looting that took place on such a scale that it infected nearly every gallery of Asian art in the West.

The way forward is neither clear nor simple. In the fall of 2022, Mother Goddess (Matrika) lay in a crate in the Manhattan DA’s overstuffed storage facility while the search continued for each of the Tanesar sculptures sold through Wiener’s gallery in the late 1960s. Mother Goddess (Matrika) and at least four more deities from the set remain in legal limbo as lawyers for the Met and other American museums raise questions about who owned the sculptures at the time they were acquired by Wiener, and whether they really did belong to the temple at the time of their theft.

One of the Tanesar figures, the sculpture purchased by the Cleveland Museum of Art, is still on display there. Others remain, for the moment, in the custody of LACMA and the Allen Museum at Oberlin College. Beyond the purview of the U.S. legal apparatus, the Tanesar goddess at the British Museum currently resides among the dutifully cataloged collection of nearly eight million objects not on view because of space limitations.

The sculptures may languish in this liminal state—crated, underground, or imprisoned in storage—but then, the liminal is where the Tanesar goddesses have existed for many years.

In 2020, I was a Fulbright scholar living in the city of Ahmedabad. I’d been researching the story of the Tanesar sculptures, having chosen the case because it involved one of the few thefts where published photographs linked looted artifacts housed in Western museums to a specific origin site. I was drawn to the beatific, yet unfussy artworks—though it was only later, as I traveled across three continents to see seven of the sculptures in person, that I fell in love with them.

In art history texts, the village of Tanesar was said to lie in the steep hillsides between the cities of Dungarpur and Udaipur, along the border of southern Rajasthan and Gujarat state. No map showed a place called Tanesar or, as it sometimes appeared in museum catalogs, Tanesara Mahadeva. News articles were of little help. A few articles in the Indian press and a 2007 piece in The New Yorker mentioned Tanesar, but only as a footnote in a seemingly unrelated story—that of the smuggler Vaman Ghiya and his arrest. As far as I could tell, no journalist or academic researcher had visited the site since the middle of the last century.

The place to start was Dungarpur. On the taxi ride from Ahmedabad, my son and I encountered a landscape where algae-rich stripes of sedimentary stone—black, charcoal, green, and blue—shone in the roadcuts. The stone industry continues to thrive in this part of northwestern India, the source of building materials, sculptures, and architectural decorations. Quarry shops sold the blue-green schist known locally as pareva, and trucks rumbled by, carrying cubes of marblelike stone.

The next morning, at a hotel in Dungarpur, the concierge told me that his in-laws happened to worship at the temple I was looking for. He put me in touch with his brother-in-law Gajeraj Ranawat. Serendipitously, I received a text that same morning from my friend Abhi Sangani, an art historian in Ahmedabad, who’d gotten a tip from his cigarette vendor with the approximate location of the temple.

This is how we ended up in the back seat of that Toyota SUV. And it was during that journey with the Ranawat family that I finally understood why finding the temple site had been so difficult. As I traced the turns of the road on my phone’s maps app, the coordinates for a temple came into view. I zoomed in. Taneeshwar Madahav Tample, the map read in English, a clumsy transliteration of the Hindi phrase beneath it: Taneshwar Mahadev Mandir. The photograph linked to the map showed the temple entryway, with its name in Devanagari script visible in blue lettering—Taneshwar Mahadev. Having studied Sanskrit and yoga philosophy, I knew that Taneshwar (or, given the conventions of Hindi and Sanskrit, Tanesvar, Tanesvara, or Taneshwara) means “Shiva” and that the phrase Taneshwar Mahadev translates to “the lord Shiva, Shiva who is the greatest god.”

Therein lay the answer to the first mystery of this tale: Tanesar was a temple, not a village. Imagine if someone had named New York City “Beth El” because of the synagogue on East 86th Street. No wonder journalists never reported firsthand from the Taneshwar Mahadev temple. If they’d been looking, they would have been searching for a village that did not exist. It’s quite possible, of course, that no other outsider had ever tried to find “Tanesar” village. After all, asking exactly how a smuggled object reached an esteemed gallery in a Western museum was not common practice until recently.

Now, after parking off the jagged road, we passed a row of stalls selling items for worship—coconuts, incense, matches, squares of metal foil, rectangles of red nylon mesh trimmed with gold thread—and followed a grand stairway up to a temple plaza. Revelers in brightly colored saris danced in a circle while men played drums and long-necked, stringed gourds. Incense and oils released a sticky, noisome odor. Smoke filled the air, and langur monkeys leapt between temple structures, with the Shisha mountain rising behind them. A priest in a white tunic and flowing dhoti pants chanted in Sanskrit and led the worshippers in a fire ceremony meant to bring auspicious energies from the planets.

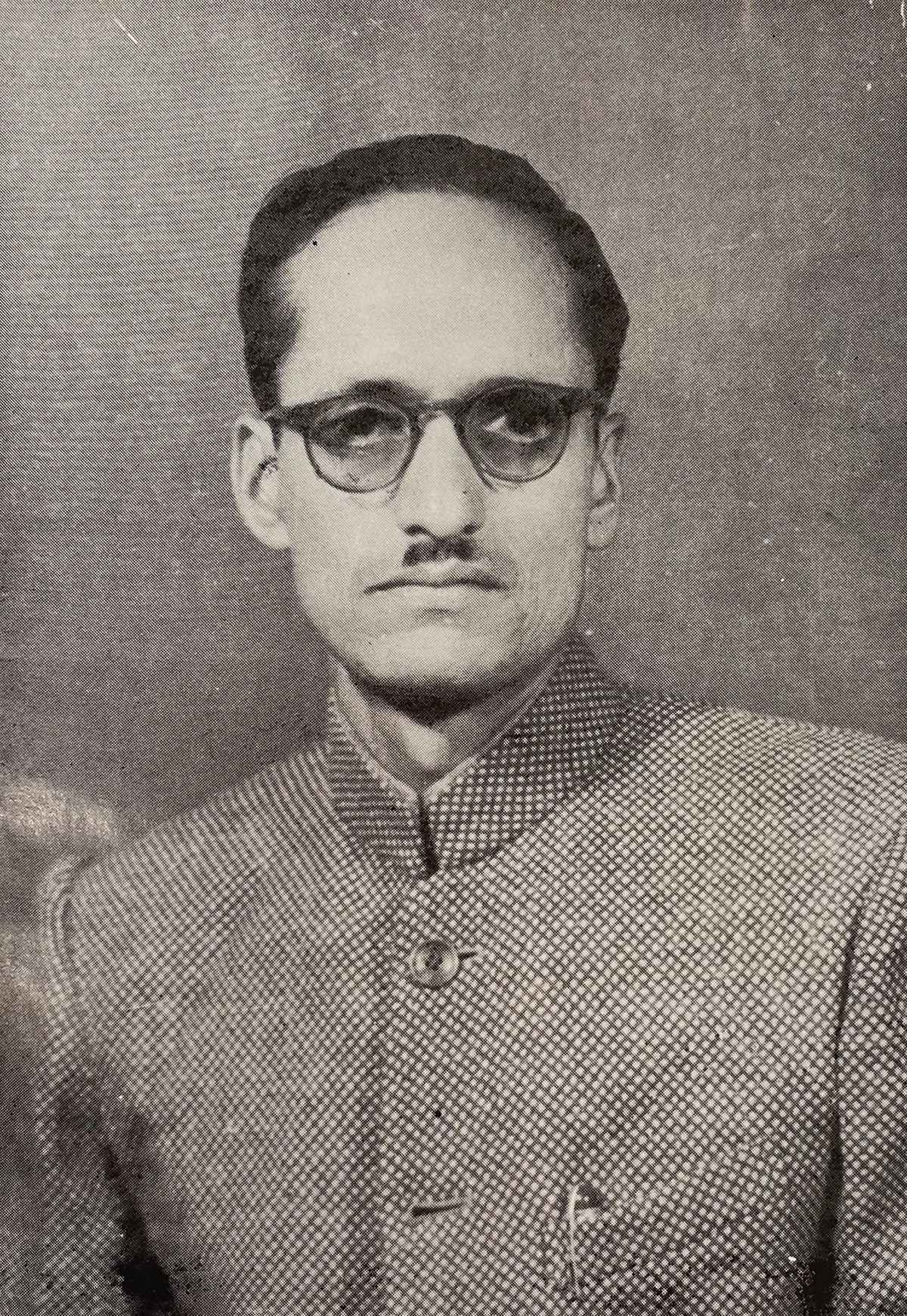

Ratna Chandra Agrawala devoted his life to the study of Indian art and artifacts. In the 1950s, he came across the Tanesar matrikas during an exploration of southwestern Rajasthan. (From Ratna-Chandrika: Panorama of Oriental Studies)

As several villagers gathered around us, my son went off to play, jumping from the retaining walls separating the plaza and the stalls and poking a stick into a warm spring that trickled down from the mountainside to the plaza. Then, with Prachi Ranawat translating, the villagers began telling me about the statues’ theft. Everyone, it seemed, knew a version of the story, which had been passed down from parents and grandparents. According to one account, a temple guard awoke one morning to discover that most of the sculptures had been spirited away in the deep of night. Alternatively, a white car arrived in the dark and took the sculptures away. Or a madman came and stole the sculptures. Or a man known to villagers by the nickname Kadva Baba came and spoke to the priest in private; money was exchanged, and shortly afterward, the sculptures were taken away. The oral history of the temple may have recorded many possible scenarios, but certain facts remained constant. Temple lootings were common in the area at the time. And although villagers often reported the thefts, police rarely recovered the loot.

I heard a great deal that day about how important the sculptures were to local life. “If someone didn’t have a child,” one person said, “they worshipped the goddesses so they could have one. If someone was suffering from a disease, they also worshipped the goddesses.” Another offered that worshipping the goddesses could bring a male child. The temple itself had been the site of a famous miracle, others said, a legend I heard about in greater detail on one of my later visits. A priest would tell me a version of the famous story of Surabhi, a cow that would wander off from its home every day and come home dry. Surabhi’s owner, angry that someone was apparently stealing his milk, secretly followed the cow to the temple, where he watched as its teats released a flood of milk onto the ground. This it had been doing every day, he learned. Later, a statue materialized on that very spot, an emanation of Lord Shiva. “That was how everyone knew that the temple was magical,” the priest explained. And in the same storytelling voice, he said, “Thirty-five years ago, a goddess statue was stolen from here. Now, the government is going to send her back.”

One thing was certain: the temple community would settle for no compensation, monetary or otherwise, in lieu of the sculptures’ return.

In the middle of the 20th century, Ratna Chandra Agrawala was the foremost archaeologist in the state of Rajasthan. He was the author of more than 400 essays and articles, many punctilious in their detail. His life’s work as a scholar and as director of museums and archaeology for the state led him to register art objects, preserve many of them in two regional government museums that he founded and managed, and argue for their importance in Indian and international arts journals. There was nothing shoddy about his work.

Born in 1926, Agrawala trained as an archaeologist in pre-independence India. In 1946, he worked on the dig that uncovered parts of the Indus Valley site of Harappa, in what is now Pakistan. Art historians who knew Agrawala during the following decades remember his utter devotion to Indian art history and his palpable joy when asked to discuss this subject, still underappreciated in the 1960s and ’70s. In one photograph, Agrawala appears in the garb of India’s educated elite of the era, wearing a Nehru jacket and thick-framed glasses and sporting a trim, narrow mustache. His thinness accentuates an intent expression in his eyes, in which I imagine—perhaps because I’ve researched his background—a hint of both pain and triumph.

Around 1957, during what Agrawala described as “exploratory tours in the regions of Udaipur and Dungarpur,” he encountered the Tanesar sculptures. For Agrawala, the artworks possessed a pleasing dissonance, with their classical proportions, indigenous features, and the sparest of religious accoutrements. They immediately won his adoration. In 1959, he described what he had found in the Indian journal Lalit Kala. In 1961, Agrawala published a second article in Lalit Kala discussing the sculptures’ art historical importance. Included were photographs of 10 of the sculptures snapped outdoors near the temple. Leaning on rocks, the gods and goddesses resemble crime victims. They are encrusted with dirt and an unguent mix of substances related to worship, which likely included milk, ghee, vermilion, and ash. Agrawala stated that the sculptures were currently being used for worship (“under worship” was the phrase he used). He went on to lament that the sculptures “remain completely besmeared with red lead and oil. It is therefore not possible to clean them for study.”

A third article appeared in the French journal Arts Asiatiques in 1965. Here, Agrawala published photos of an additional sculpture and more fully described the artworks and their material, the luminous blue-green schist. One of the pieces, he wrote, “presents a lady with her head bent in a graceful pose. This is unique in Indian Art. She puts on the typical sārī and the scarf is appearing on her right arm. The facial expression here is extremely elegant and so also is the case with round ear-lobes, single beaded necklace, broad face, robust breasts, etc.” He declared the sculpture to be “a piece of superb workmanship,” adding, as an aside, “the hair decoration is equally charming therein.”

The 1959 article identified the temple as Tanesara-Mahādeva and its location as being near the village of “Parsada,” a Sanskritized version of Parsad. Agrawala didn’t mention Parsada in his 1961 article, though he did cite his first article in the footnotes. But by the time the sculptures had arrived in the West, it was the 1961 article, not the original publication, that was the standard source on the subject, the primary bibliographic reference for authors of museum catalogs. This is how Parsada got dropped from the record, replaced by the fictional Tanesar.

But why didn’t Western museums track down Agrawala’s primary source material? One day, I arrayed before myself, in chronological order, each bibliographic reference to the Tanesar artworks from 1959 through the 1980s, hoping to understand how this scholarly laziness had occurred. The first mention of the sculptures in an American publication appeared in a 1971 issue of the Allen Memorial Art Museum Bulletin of Oberlin College. That issue was devoted to an exhibition of works belonging to a prominent collector and Oberlin alum, Paul F. Walter. Among the artworks that Walter had recently donated to the Allen Museum was Deva, a Tanesar sculpture featuring a lithe young man with a serene, transported expression, carved from the blue schist.

One of the essays in the Bulletin, written by the art historian Pratapaditya Pal, curator of Indian art at LACMA, described five sculptures from the Tanesar set that Wiener had acquired and then sold to prominent American curators and collectors. This included images of an additional sculpture, bringing the total number documented in photographs to 12. The essay, a tour de force in interpretive writing, marked the sculptures’ entrée, like debutantes, into a larger art historical conversation beyond the limited audience of India’s rarefied Lalit Kala.

Pal’s elegiac descriptions explored theories regarding the identities of the gods and goddesses, their art historical connection to other artworks from nearby sites and distant centers of artmaking during the fourth- to-sixth-century Gupta Empire, and the trope of the mother in South Asian art. “Each of the pieces magically seems to have captured, as in a candid snapshot, a fleeting moment of joy and playfulness,” he wrote. The matrika in the Cleveland Museum of Art “appears to be smiling as she tries to restrain her child. This sense of radiant motherhood is more explicitly expressed in these matrikas from Tanesara than in any other Indian sculptures.” Deva had “the physical properties of a human being,” and its face evoked “supra-human serenity and compassion.”

The Taneshwar Mahadev temple complex, where the sculptures had been housed. Local residents tell several versions of the story of how the figures were stolen. (Courtesy of the author)

The problem was, for all the flourishes of Pal’s lushly detailed and celebratory narrative style, the essay was also riddled with mistakes. It incorrectly identified the “Tanesara-Mahadeva” temple as a village (with a footnote erroneously ascribing that detail to Agrawala’s 1961 article). The name of the famous regional rock was changed from pareva to pavena. And the name of a sister site that Agrawala had also explored morphed within the article from Kalyanpura to Kotyarka. These mistakes and others subsequently appeared in later works of scholarship.

It seemed odd that the editors didn’t catch these lapses. But when I read the introduction to that issue of the Bulletin, I realized that a general romantic sensibility had prevailed over the mundane requirements of scholarly fidelity. “To Western ears,” wrote Richard Spear, the Allen Museum director, “Bhagavata Purana, Ramayana and Ragamala are strange sounds, as remote as Malwa, Hyderabad and Jaipur.” “Tanesar” was not a place where people lived and worshipped but a fanciful, fairy-tale locale. Further embroidering this theme of exotic-domestic interplay, Spear described Walter, the collector and donor, as someone who was “as likely to be met in the studio of a young artist in lower Manhattan or a London auction of Whistler etchings as in the Doris Wiener Gallery of Indian Art.” The relationships between dealer, collector, and museum curator were cozy enough to completely subsume any question of how the artworks were attained.

The fairy-tale atmosphere also created an illusion of buyer innocence. It was all too common in mid-century America to deflect blame from those who acquired artworks that had been purloined by shady dealers. A charade of not knowing the specifics of any origin site insulated those at the top of the antiquities trafficking chain—the Rockefellers, respected collectors, and museum curators who had purchased or accepted the sculptures as donations. Even today, this false ignorance prevails, in spite of its illogic. “If you didn’t legitimately acquire the property in the first place, you can’t pass on title,” Manhattan Assistant District Attorney Bogdanos told me. “A stolen object never reacquires goodness. Once stolen, always stolen.”

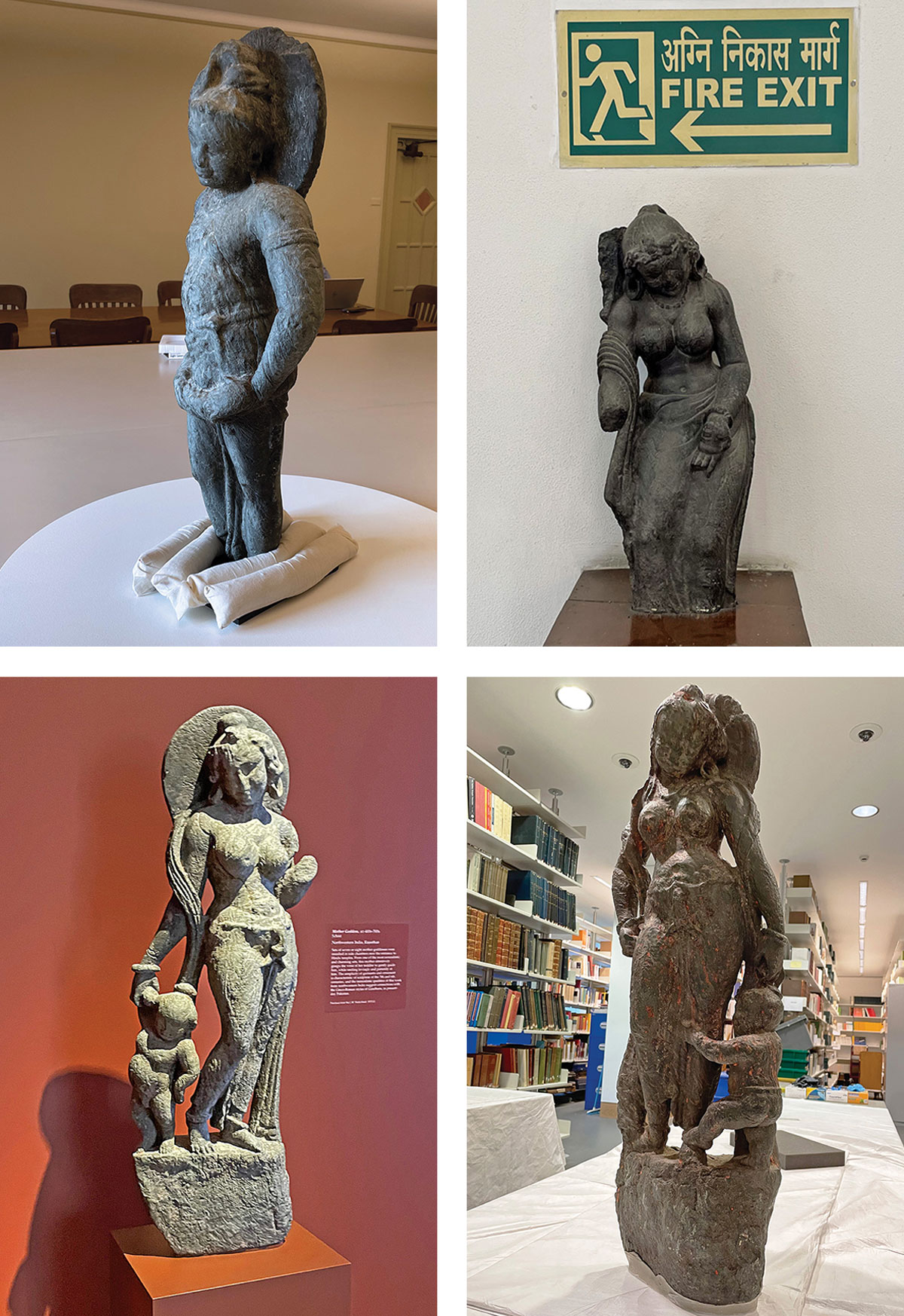

Clockwise from top left: Tanesar matrikas in the collections of Oberlin College,the National Museum in New Delhi, the British Museum, and the Cleveland Museum of Art (Courtesy of the author)

By drawing attention to the Tanesar artworks, Ratna Chandra Agrawala—no matter how noble his motives—ended up contributing to their theft. He was part of a nationalistic movement, just a decade after Indian independence, to increase global recognition for indigenous statuary. This mission was shared by the editors of the Bombay-based journal Marg, which in 1959 cited Agrawala among the Western and Indian art historians and archaeologists who inspired the “intelligentsia” and “men and women of culture” to appreciate “the remarkable tradition of carving which has miraculously survived in Rajasthan.” The editors also “earnestly appeal[ed] to the archaeologists” to “accord proper display” and facilitate “direct contact with the unknown masterpieces.” Agrawala did this, in part, by relocating two of the Tanesar sculptures to his government museum in Udaipur.

Today, these remain in the Indian government’s custody, displayed in underwhelming circumstances that would surely rankle Agrawala’s ghost. One is easy to miss, in a busy section of hallway at the National Museum in New Delhi, crowded between a potted plant and an exit sign. The day I visited, crowds of chattering secondary students in government school uniforms raced past, oblivious of the goddess. The other matrika, more dispiritingly, resides at an Udaipur government gallery, in a desolate room that is often closed to the public. When I finally managed to get in, the lights didn’t work, and chipmunks were scampering along the rafters. The matrika stood behind a case so rarely dusted that I could barely read the identifying label through the glass. But when I was able to make it out, I saw that the label had been swapped with that of a nearby sculpture from a different site. If Agrawala might have frowned at this sad scene, he also may have worn a small smile, knowing that the sculptures had been kept safe from looters all these years. Here the matrikas rested, ready for future generations—perhaps even those scores of secondary students in New Delhi—to embrace the appreciation of Indian art that he and his cohort had worked so hard to instill during the 1950s and ’60s.

Agrawala, at the time, surely knew that the nationalist push for art appreciation was indirectly encouraging the activities of looters, and the 1960s would indeed witness a frenzied black market targeting the newly recognized statuary. “There was a sense that if you got it into a museum, at least you were protecting it from some of the thieves,” said Padma Kaimal, Batza Family Chair in Art History at Colgate University and author of Scattered Goddesses: Travels with the Yoginis, about a set of sculptures exported from southern India in the late 1920s. “The atmosphere was Wild West, help yourself. It was really difficult to protect the art.” Agrawala, she speculated, probably “saw these amazing pieces, really admired them, and knew how vulnerable they were.”

By the time my son and I were traveling in India in 2020, evidence of that rapacious mid-century market, of pillage, was everywhere. Whether touring little-known ruins or UNESCO World Heritage sites, my son got in the habit of playing a fun scavenger hunt game. He ran from niche to niche pointing out places where sublime figures of gods and goddesses were no longer extant. “Missing!” he declared to the local day-trippers. They were nonplussed. It had been decades, after all, since India had suffered a wholesale theft of its heritage.

Starting in the late 1950s, police began to find dust-covered, sumptuous artworks on the dirt floors of godowns. This Indo-Portuguese borrowing from the 16th-century spice trade refers to warehouses and the objects bound for export within. The objects discovered in a Gujarati cache in 1959 lay “in pitiable disarray,” one art historian reported. In 1968, police confiscated seven museum-quality stone sculptures from a godown in Bombay. Officials were able to arrest a driver and his accomplice, but the vandals jumped bail. After spending several months trying to locate the sculptures’ origins, authorities gave up and released them to the Prince of Wales Museum in Bombay. The museum’s announcement of the acquisition reported on a larger scene in which certain areas of the country were “dacoit-infested” ( dacoits are armed bandits), with outlaws “acting in cooperation with some art dealers.”

In December 1969, Robert McCormick Adams Jr., an archaeologist who went on to become Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, published a letter to the editor in The New York Times. The letter responded to an early draft of UNESCO’s 1970 Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property. Signed by an additional six archaeologists, the letter noted a lack of “effective measures to curb the trade … by the museums and art galleries that are among its principal beneficiaries.” The letter also pointed out that federal laws (which provide tax exemptions for museums) “in fact sanction looting.”

Those museums began to receive sleeves in the mail from museum directors in India containing photos of hot artworks and requests to keep an eye out. One arrived at the Cleveland Museum of Art from the archaeological curator of the Prince of Wales Museum in Bombay, by certified air mail. The curator, B. V. Shetti, wrote, “I am enclosing herewith 14 black and white photographs out of the 23 [Indus Valley] seals which were stolen from our Museum on 27th February, 1970. … Kindly keep us informed if you happen to know anything in this matter.”

Sherman E. Lee, chief curator of Oriental art and director at the Cleveland Museum of Art at the time, had just then acquired two nearly identical, unprovenanced seals from William H. Wolff, who once discussed with The New York Times his “clandestine” and “illegal” export of antiquities from Asia. After determining that the Cleveland seals were not from Bombay, Lee wrote a letter to Shetti:

We have examined the photographs and lists and hasten to report that we are not aware of any of these objects being on the market at the present time. You may rest assured that if they do appear in any way, we will immediately inform you.

May I add that it would be most helpful for museums with significant Oriental collections in this country if you and the other professionals in India would keep us informed of thefts of works of art. We are as anxious as you are to prevent this activity and to restore the works to the proper owners. The more information we get, the better we can cooperate.

By the time he sent this letter, Lee had already purchased one Tanesar mother from Wiener, knowing full well the likelihood it had been “stolen” or “illegally acquired.” I learned this by studying correspondence, located in the archives of the Cleveland Museum of Art, between Lee, Wiener, and others.

This museum has taken a leadership role in investigating questionable acquisitions in its collection and exploring how present-day curators can right the transgressions committed by those who came before. The museum’s curator of Indian and Southeast Asian art, Sonya Rhie Mace, devoted two years to research into the provenance of a 10th-century stone sculpture of the god Hanuman that resulted in its transfer to the Kingdom of Cambodia in 2015. More recently, Mace worked closely with the National Museum of Cambodia to curate a multimedia presentation featuring a larger-than-life stone sculpture of Krishna that had survived only in fragments.

“There needs to be a well-considered conversation about what can happen in the future, because so much happened in the past that cannot be changed,” Mace told me. “How do we understand a troubled past so it doesn’t happen again? I tried to do this with the Krishna exhibition, to show how complex and ambivalent the history of a single object can be. For the works that are in our care, let’s look at them one by one, tell their stories, and try to reach out to countries of origin. We need an open approach to talking about what’s best for the sculptures.”

In the months before the Manhattan DA’s office began its investigation, Oberlin College’s Asian art curator, Kevin Greenwood, and museum director, Andria Derstine, consented to meet with me concerning my research into the Tanesar sculptures. (Derstine later declined to speak, once the investigation commenced.) Other institutions have been less forthcoming. Officials at LACMA and the Met ignored or rejected my multiple attempts to discuss the Tanesar sculptures in their collections. The Met, moreover, left up erroneous website content concerning the sculptures even after I brought up published sources that could have helped correct the mistakes.

By 1967, at least six of the original Tanesar artworks had traveled across two oceans and reached Wiener’s New York gallery. Wiener sometimes called them “black stone matrikas.” In March 1968, she wrote to Lee, “Mr. & Mrs. Rockefeller came to see the Matrika stones, and will be in touch with me or you, regarding their choice. At that time, as per our conversation, we will send the other to you.”

Doris Wiener died in 2011. In 2016, she was posthumously named in a Manhattan criminal court complaint for conspiracy to “buy, smuggle, launder, and sell millions of dollars’ worth of antiquities stolen from Afghanistan, Cambodia, China, India, Pakistan, and Thailand.” The complaint stated that she and her daughter, Nancy Wiener, along with others, had “trafficked in illegal antiquities for decades.” In 2021, Nancy Wiener accepted a plea bargain in exchange for providing information about smuggling networks engaged by herself and her mother. This information, in turn, contributed to the DA’s investigation of the Tanesar sculptures that led to the seizure of Mother Goddess (Matrika) at the Met in the fall of 2022.

The complaint and plea bargain named two smuggling rings operating in India supported by the Wiener family business and run by dealers named Om Sharma and Sharod Singh. And although the DA’s office would not confirm the name, a known middleman had to have connected the dacoits who looted the Tanesar temple in the early 1960s to Doris Wiener.

Less a focus of the DA’s complaint were the fluid social ties connecting the Wiener family with the world of museum directors and benefactors. “I have recently returned from an extended trip to India,” Wiener wrote chummily to Lee in May 1967. “My activities there, besides listening to tremendous amounts of gossip and shop-talk, was to acquire a fine collection of Indian miniature paintings and a very fine Persian manuscript which just arrived. I would be pleased to see you again when you come to New York.”

Over time, Wiener’s gallery moved to Fifth Avenue, in a building facing the steps of the Met. A business-meets-pleasure lack of boundaries characterized the industry. “As usual, the dealer knows more than the curator,” Lee wrote to the collector Robert H. Ellsworth in 1966.

Lee had become aware of the Tanesar sculptures’ existence as early as November 1961. That’s when Ratna Chandra Agrawala mailed Lee a dossier containing a dozen of his own recent articles that more than likely included the two in Lalit Kala discussing the sculptures. “It is hoped,” Agrawala wrote, “that [the papers] will be of some interest to you. … I shall also look forward to your visit to Rajasthan in the near future.” Whether or not the 1959 and 1961 articles were included in the batch, Lee had the 1961 article in his possession while discussing with Wiener the sale of one or more of the sculptures.

In September 1967, Lee wrote to a consultant, Vinod P. Dwivedi, at the National Museum of Delhi about a conflict. He was seriously considering the purchase of a Tanesar matrika on offer from Wiener:

One thing in particular has come up which I must ask you about and rely upon your confidence and discretion. I do not wish to be involved in any way in the acquisition of any material which has been ‘illegally acquired.’ Please note, I don’t say ‘illegally exported,’ but ‘illegally acquired.’

In the No. 10 issue of Lalite Kala, October, 1961, pages 31-33, there is an article by R. C. Agrawala which includes illustrations of nine sculptures from Tavesara, described as ‘Under Worship.’

I am informed that these pieces are now in the United States, in the hands of a dealer. Has there been any report or information about these pieces being stolen or in any other way illegally acquired? Did the village sell the pieces?

Dwivedi, after speaking to Agrawala, responded that there was no report of a theft from “Tavesara” but that “the villagers never sell any image under worship.”

In May 1968, when the sale was close to final, Lee finally asked Wiener about the matter directly: The “only question is whether the piece was originally sold from the village or whether it was stolen. What kind of guarantee of title can you provide … ?”

By 1970, Lee had acquired the Tanesar sculpture for his museum’s collection, paying $10,500. (It’s possible that more sculptures were offered and considered.) Soon after, the Cleveland museum mailed an 8-by-10 glossy of the acquisition to Oberlin College for publication in its Bulletin. That Lee knew the sculpture’s origin story is evident from the photo, which bears the label “from Tamesara-Mahdeva, (ca. 30 miles from Vdaipur).”

How did Wiener succeed in placing the sculptures with curators and collectors at the highest echelon of American society? Most of the collectors had close connections to Pratapaditya Pal, author of the 1971 article in the Allen Museum Bulletin. Born in East Bengal and raised in Calcutta, Pal is now 87. His scholarly works are extensive, and he has served as curator of South Asian art at some of the finest museums in America—in Chicago and Boston, as well as Los Angeles. He also knew everyone in the art world, and he did much of his work in an age of schmoozing and long lunches at French restaurants.

The matrika at the British Museum was retrieved from storage, allowing the author to feel its “extraordinary leadlike heft.” (Courtesy of the author)

In his writings, Pal mentions his friendships with not only Wiener but also Paul Walter and Nasli Heeramaneck, then a respected collector in New York. Heeramaneck owned three Tanesar sculptures at one time or another. Another close friend, and one of Pal’s advisees, was Christian Humann, a prolific collector who passed away in 1981. The first blockbuster touring exhibit of Asian statuary—“Sensuous Immortals,” curated by Pal—was made up of Humann’s bronze and stone artworks. Among the treasures of the show was Mother Goddess (Matrika)—the Tanesar goddess seized from the Met last year. “Sensuous Immortals” traveled to five North American cities between 1977 and 1979, often crossing paths with another blockbuster touring museum exhibition, one that defied all previous expectations for art world profitability and bore the taint of theft—the “Treasures of Tutankhamun.” The American museum as an institution had entered a new era of commercialism. If precisely naming the origin site of a set of highly valued artworks would have cast doubt on good title, and therefore undercut profitability, it’s no wonder that such a detail would have been left off, that certain errors in a journal article would go uncorrected. In art world circles, the imprimatur of having once been displayed in “Sensuous Immortals” often stands in for an object’s respectability. And yet, Mother Goddess (Matrika) is not the only sculpture from the show, or from Humann’s “Pan-Asian collection,” to have been tainted by questions of provenance. Another is the 10th-century stone Hanuman transferred to Cambodia from the Cleveland Museum of Art in 2015. Yet a third is the 11th-century Celestial Woman Beneath a Mango Tree, which was on view at the Denver Art Museum from 1965 until 2019. This figure was matched to photos taken at a temple in central Rajasthan in 1960 and published on the website Plundered Past. After being confronted with the information, the Denver museum quietly returned the sculpture to India—without any public mention of the transfer. A fourth is the bronze Hanuman Conversing from the 11th century, currently on view at the Met. Just this past December, researchers in Puducherry, India, linked it to a theft sometime around 1960, using photographs archived at the city’s French Institute.

Connecting an object to its original site is important for two reasons. Doing so preserves the integrity of its art historical record, and illuminates and evaluates the legality and morality of its removal. Neither of these concerns seems to have preoccupied Pal. “Fortunately,” Pal wrote in 2021 in a fond reminiscence of “Sensuous Immortals,” “in the 1970s, there were no ‘provenance issues’ that would become such a headache for museum professionals and collectors by the last decade of the century.”

This, however, is another fairy tale. “Sensuous Immortals,” after all, concluded just one year before the publication of Foreign Devils on the Silk Road, the British journalist and historian Peter Hopkirk’s exposé on the pillaging of Central Asian Buddhist art by explorers working for colonial powers at the turn of the 20th century. He describes a case in which the British-Hungarian archaeologist Aurel Stein, exploring Buddhist sites in the Taklamakan Desert in the early 1900s, “used a saw, carefully inserted behind the frescoes,” and had paintings “cut into pieces, later to be carefully reunited after their long and arduous journey home by camel, pony, yak or other means.” The bulk of this cache is now in storage at the British Museum. Hopkirk asked his readers to judge for themselves “the morality of depriving a people permanently of their heritage.”

Two years after the publication of Hopkirk’s book, in 1982, the art historian Joanna Gottfried Williams declined to include Indian sculptures held in American museums or collections for her landmark history The Art of Gupta India: Empire and Province. Although her argument centered on the need for art historical context, her comments bore the whiff of condemnation. She fingered a text by Pal specifically for its “deliberate inclusion of works without the unimpeachable credentials of those recorded in situ in India.”

This hybrid figure currently resides at the Taneshwar temple—the sculpture’s torso is ancient, but its head dates to a later period. (Courtesy of the author)

Not long ago, I reached Pal on the phone, though he did not have much to say about the Tanesar artworks beyond what he has previously written. “If this is another question of repatriation and all this, I don’t have time to discuss it right now,” he said, suggesting that I write to him about the matter. He did, however, say that in his view, the sales of the artworks should be considered in the context of the ratification date of the UNESCO convention to curtail international black marketeering in antiquities. “If works were acquired before 1970,” he told me, “as far as I’m concerned, those sales are perfectly kosher.” He didn’t want to speak about the larger subject of the Tanesar sculptures’ export, which is a shame, because the story he could tell about the world of 20th-century collecting and museums would be illuminating, to say the least.

Today, the shortsightedness of the past is often invoked to contextualize the open secret of museum-bound loot in the 1960s and ’70s. Nancy Wiener, in her 2021 plea bargain, described “a market where buying and selling antiquities with vague or even no provenance was the norm. Obfuscation and silence were accepted responses to questions concerning the source from which an object had been obtained. In short, it was a conspiracy of the willing.” Wiener’s passive language nicely insulates museum directors from participation in that conspiracy.

This world of make-believe and false facts, where the notion that no one would notice or care if the name of a town was wrong, reminded me of the condescending practice of sculpture replacement. This is a trick used by temple looters. They steal a valuable devotional sculpture and then deposit a cheap fake or a newer, less valuable object in its place. Then, worshippers have something to propitiate, and the looters—and others—get rich.

At the Taneshwar temple on my first visit, villagers showed me a statue that some worshippers believed to be a replacement. Its body was covered in red mesh fabric bordered with gold. Foil, ash, and vermilion stained its exposed limbs and face. Only the head was visible. On a later visit, though, I saw that the sculpture’s torso was indeed ancient. The newer head had been balanced, off kilter, on top of the body. This goddess was a beautiful Frankenstein. Embodying old and new, the figure had become an object of worship on its own terms.

There was a strange, raw power in this indigenous, living artwork. I’d felt something similar in my pilgrimage across three continents—North America, Europe, and Asia—to lay eyes on or even touch as many sculptures from the set as possible. I was able to feel the extraordinary leadlike heft of the goddess at the British Museum. After I submitted a research request, an attendant retrieved this matrika from storage, bringing her to me in a wooden cart labeled oriental. At the Allen Museum at Oberlin, after a similar research request, the curator brought Deva out of storage and rotated him on a lazy Susan–style pedestal. We watched, enraptured, as the beautiful blue-green stone caught the light in different ways while the figure spun. And at the Met and in Cleveland, I saw the sculptures under precisely arranged decorator’s bulbs, which showed off their sublime, otherworldly features, but also their maternal air of knowledge and contentment.

The day I saw the old-new goddess, I was similarly moved. I stood in the alcove and imagined how this place might vibrate should the spirits of the original Taneshwar goddesses join this modern, vernacular goddess. Sublime art celebrates and simulates the richness and density of life, and all of these goddesses have done just that. The past was unrecoverable, but perhaps something more powerful would soon come to be. I wondered what it would be like to feel the energies of the goddesses coalesce in one place as they hadn’t in more than 60 years. I envisioned a land where gods and goddesses were returned home in spite of the mammoth forces of commerce, prestige, and power. I wondered if my fantasy might one day become real.