In a Flight of Starlings: The Wonders of Complex Systems by Giorgio Parisi; Penguin Press, 144 pp., $24

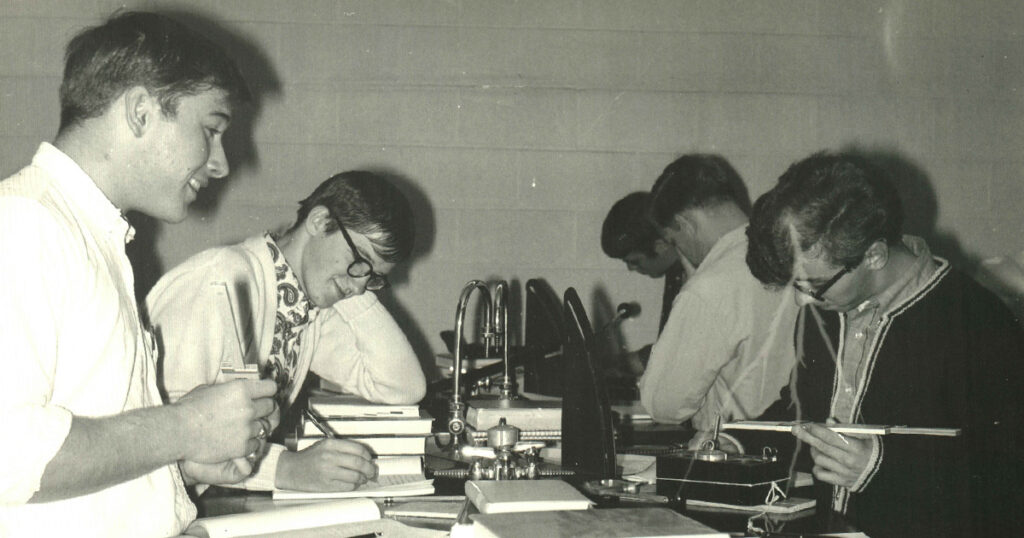

As unlikely as it sounds, we’ve entered the age of the physics beach read—a breezy stroll through some branch of the science, with alternating touches of profundity and whimsy. Recent exemplars include Seven Brief Lessons on Physics by Carlo Rovelli and Astrophysics for People in a Hurry by Neil deGrasse Tyson. The latest aspirant is In a Flight of Starlings, a slender, uneven collection of essays by Giorgio Parisi about his life in physics, from his student days in Rome to the work that won him a share of the 2021 Nobel Prize in physics.

The title refers to Parisi’s research on the eerily amorphous flocks that starlings form each night at dusk, flocks that twist and shape-shift like something conjured by a wizard. Parisi wanted to understand why starlings form these flocks, called murmurations, and what rules govern their behavior. He took inspiration from work in statistical physics that involves scaling up from simple atoms and molecules to complex collective phenomena like boiling, melting, and superconductivity. Part of the title essay focuses on the technical struggles involved with tracking thousands of individual birds, especially in three dimensions. Computing power also hindered him. Although the project was conceived in 1990, his team had to wait until 2005 to start because cameras simply weren’t able to capture high-resolution digital images.

Parisi concluded that starlings form murmurations both to signal other starlings that they’ve found a warm roosting spot for the night (starlings are sensitive to cold and often drop dead overnight if not protected) and to help the birds protect themselves against hawks and other predators (it’s much easier to pick off stray starlings than to snatch one out of a jumbled mass).

Alas, aside from the obligatory declarations of wonder, Parisi doesn’t get very lyrical in describing the beauty of flocks of starlings. And this lack of a poetic register hobbles other essays, too. It’s not that Parisi cannot escape the mindset of a scientist—he offers several sharp, everyday analogies throughout the book. (My favorite involves how the simplified models of reality that scientists build can nevertheless reveal profound truths about nature, in much the same way that playing Monopoly can illustrate certain truths about capitalist economies—that it takes money to make money.) It’s more that Parisi’s prose never soars. I never got a sense of awe or wonder—no wows.

Even when writing about the work that won him the Nobel Prize—on so-called spin glasses, a complicated magnetization state in metals—Parisi doesn’t really explore why the topic grabbed him, beyond noting that it was “interesting.” Moreover, he won the Nobel in part because the underlying principles that explain spin glasses can be broadened to illuminate the behavior of any system in which disordered individual agents interact in complex ways. Possible applications, Parisi writes, include analyzing “websites, financial traders, stocks and shares, people, animals, components of ecosystems, and so on.” I suddenly perked up, hoping he’d expound on the deep connections between all these disparate things. Instead, he simply drops the topic and starts talking about another “very interesting problem,” one that involved packing different-sized spheres into a box. It made me hungry to see what, say, physics writer Alan Lightman might have done with these subjects.

As someone who writes about science history, I have long grumbled about how misleading modern scientific papers are. I understand the need to present scientific findings in a clean, concise way, but the papers also omit all the false starts, blind alleys, broken equipment, and dumb mistakes that beset real scientific research every day. By omitting all the human stuff, the papers fail to explain how science really gets done. Parisi raises a related complaint—that scientific papers omit all sense of intuition. Indeed, the best sections of the book explore the role of intuition in scientific thinking. He quotes a friend who says that “a good mathematician understands immediately which mathematical statements are true and which are false, whereas a bad mathematician has to try to prove them in order to know.” The same applies to science: the early stages of any project are chaotic, and the data can be confusing and even contradictory. Scientists need intuition to cut through the mess and focus on the most promising explanations.

Much of this intuition is unconscious and, while still grounded in physical brain processes, remains murky and hard to reconstruct. And for whatever reason, that vagueness makes scientists uncomfortable. “In almost all texts written by scientists,” Parisi notes, “these themes are taboo.” So it’s refreshing to see a scientist, especially one of Parisi’s stature, honestly discuss the fuzzy side of scientific thinking, and not just during the early, groping stages but in the technical phases of a project, too. “The physicist sometimes uses mathematics ungrammatically,” he admits, “a license that we grant to poets” as well.

In the last pages, Parisi compares writing his book to translating Chinese poetry. In Chinese poems, especially older ones, the words are both words and pictures—poetry and painting fused. As a result, attempts to translate those poems into another language inevitably lose something. But in a good translation, we can still glimpse the underlying lyricism, however imperfectly. Parisi says that writing for a popular audience about physics is something like that. He has to omit the mathematics and other technical aspects that give the work its aesthetic pleasure and power. But in good translations, laypeople can still catch a glimpse of the underlying wonder. Flight of Starlings, Parisi writes, “is my attempt to convey to a wide readership something of the beauty, importance, and cultural value of modern science.” Does he succeed? At times, yes. But the book ends up stranded between different genres—not quite a beach read, not quite a memoir, not quite a pop-science primer on modern physics. Perhaps it’s not unlike the hodgepodge of science itself, then—or even a shifting, amorphous murmuration of starlings.